An outstanding Jun purple-splashed bowl, Northern Song – Jin dynasty, 12th – 13th century

Lot 3605. An outstanding Jun purple-splashed bowl, Northern Song – Jin dynasty, 12th – 13th century; 14.9 cm. Lot sold 7,560,000 HKD (Estimate : 6,000,000 - 8,000,000 HKD). © Sotheby's 2022

Provenance: John Audley, Berkeley Square, London, 1911 or earlier.

Collection of William Cleverly Alexander (1840-1916), bought 13th June 1911 for £300.

Collection of the Misses Alexander.

Sotheby's London, 6th/7th May 1931, lot 145 (£370).

Collection of Sir Rex Benson (1889-1968).

Collection of Mrs Rex Benson (1907-1981).

Sotheby's London, 14th April 1953, lot 143.

Sydney L. Moss, London, 1953.

Collection of Raymond F.A. Riesco (1877-1964), no. 102v.

Collection of the London Borough of Croydon (c.1959-2013).

Christie's Hong Kong, 27th November 2013, lot 3103.

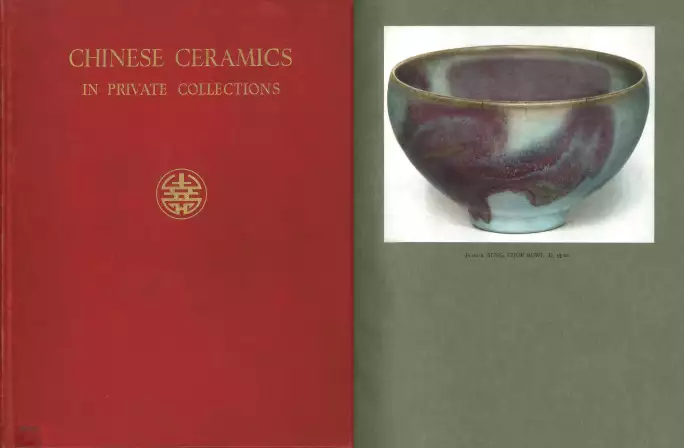

Literature: R.L. Hobson, Bernard Rackham & William King, Chinese Ceramics in Private Collections, London, 1931, col. pl. 2.

London Borough of Croydon, Riesco Collection of Chinese Ceramics. Handlist, Croydon, 1987, p. 7, no. 52.

Regina Krahl, ‘China Without Dragons. An Exhibition of The Oriental Ceramic Society’, Orientations, November/December, 2016, p. 96.

Jane Sze, ‘Some Forms and Uses of Jun Wares’, Arts of Asia, November-December 2020, vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 112-17, fig. 4.

Jane Sze, The Rainbow Aloft: Jun Ware, Hong Kong, 2020, pl. 9.

Rose Kerr, Dazzling Official Jun Wares: From Museums and Collections Around the World, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2021, p. 38, pl. 18.

Exhibited: Ausstellung Chinesischer Kunst, Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst und Preußische Akademie der Künste, Berlin, 1929, cat. no. 564.

The Town Hall and later the Clock Tower, Croydon (after 1964 until 2013).

China Without Dragons. Rare Pieces from Oriental Ceramic Society Members, The Oriental Ceramic Society, London, 2016, cat. no. 76.

The Alexander Jun Bowl

Regina Krah

Purple-splashed Jun wares from kilns in Juntai, Yu county, Henan province, are arguably the most striking and flamboyant ceramics made in China during the Song (960-1279) and Jin (1115-1234) periods, and at the same time among the most contemporary in design. Among this art-historically outstanding production, the ‘Alexander Jun bowl’ is one of the most successful and impressive pieces. Its superbly proportioned shape spells balance and harmony, its extremely vivid colouration and abstract glaze pattern add dynamic and tension. Its size is exceptional. The well-rounded profile invites the viewer to pick the bowl up with both hands, the asymmetric pattern makes it compulsory to turn it around.

Song connoisseurs were extremely advanced in their taste. The Song ruling elite, right up to the imperial court, was able to appreciate simplicity, abstraction and a certain rustic beauty. Only thus can one explain the high regard nearly a millennium ago, for a vessel such as this bowl, which could be the work of a contemporary artist.

‘Jun’ ware, with its ravishing purple-and-blue colour combination, is one the most daring creations in the history of Chinese ceramics and certainly the most flamboyant of the major wares of the Song dynasty (960-1279). This period, which can be regarded as the first classic age of Chinese ceramics, saw a particularly large number of outstanding kiln centres throughout China compete for attention. No other manufactory achieved similarly bold and colourful results. Nigel Wood discusses the uniqueness of Jun glazes, which derive their bright sky-blue glaze colour not from a pigment but from an optical illusion – indeed not unlike the blue of the sky – as minute spherules of glass in the glaze are scattering blue light. He writes “… the fully developed Henan Jun glaze was a high-fired effect unique to China ... In addition to accurate mixing and careful selection of raw materials, Henan Jun glazes also needed unusually long firings and slow cooling for their special characters to develop.” (Nigel Wood, Chinese Glazes. Their Origins, Chemistry and Recreation, London, 1999, p. 119 and p. 125). The red derives from a copper-rich pigment applied to the blue glaze, which is difficult to control in the firing and thus unpredictable in its outcome. This chance effect is the ware’s particular attraction, making every piece unique, with individual patterns and tonal variations created as if by nature.

The engaging copper-splash pattern on the present bowl comprises three distinct, well-shaped patches on the outside, spaced far enough apart to be well surrounded by plain blue glaze, and giving the bowl very different aspects when seen from different sides. On the inside, the splashes are concentrated around the top, from where they run down in an asymmetric pattern and where they are beautifully contrasted with the pale greenish glaze tone at the rim.

The present bowl is basically unique, but the Palace Museums in Taipei and Beijing have one comparable example each, both of slightly different proportions, with the splashes less clearly defined, and with the foot basically unglazed. The piece in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, is illustrated in A Panorama of Ceramics in the Collection of the National Palace Museum: Chün Ware, Taipei, 1999, pl. 87, pp. 210-11 (fig. 1). Four pages have been devoted to the Palace Museum bowl in Beijing, which is more slender, in Jun ci ya ji. Gugong Bowuyuan zhencang ji chutu Junyao ciqi huicui/Selection of Jun Ware. The Palace Museum’s Collection and Archaeological Excavation, Beijing, 2013, no. 37, pp. 114-17 (fig. 2). A slightly smaller purple-splashed bowl of this elegant rounded form, from the Eumorfopoulos collection is illustrated in R.L. Hobson, The George Eumorfopoulos Collection of Chinese, Corean and Persian Pottery and Porcelain, London, 1925-8, vol. 2, pl. B 78, and was sold in our London rooms, 29th May 1940, lot 185.

fig. 1. A Jun purple-splashed bowl, attributed to the Yuan dynasty, National Palace Museum, Taipei.

fig.2. A Jun purple-splashed bowl, Northern Song–Jin dynasty © Palace Museum, Beijing.

Bowls of similar shape are also known with plain blue glaze, but are very rare with copper splashes. A bowl of similar size is also in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from the collection of Charles B. Hoyt, glazed all in purple on the exterior and on the interior completely covered with sky-blue glaze, illustrated in Wu Tung, Earth Transformed: Chinese Ceramics in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston, 1998, pp. 68-9, where the author remarks that besides the dazzling colours “a tea connoisseur of the early twelfth century would most likely also have appreciated the bowl’s sensuous contours and the fullness and thickness of the potting”. All these related bowls differ in their proportions and the style of their splashes, clearly documenting that they were produced individually, independent of the large-scale series production the Juntai and other kilns were engaged in at the same time.

With its well-shaped silhouette and strong colouration, the Alexander Jun bowl is closely reminiscent of the famous Jun ‘bubble bowls’, which, however, are much smaller (less than 10 cm) and much less rare. ‘Bubble bowls’ are comparable in the quality of their brightly copper-decorated glazes, their clear splash patterns and their well-proportioned shapes, and also seem to have been individually done; see, for example, a bowl in the Palace Museum, Beijing, in Jun ci ya ji, op.cit., no. 36.

Splashed Jun wares were made by a number of kilns in Henan, but pieces of the best quality, with intense and distinct copper splashes, have been recovered particularly from the Yuxian kilns. Related fragments from the kiln site are illustrated in Gugong Bowuyuan cang Zhongguo gudai yaozhi biaoben [Specimens from ancient Chinese kiln sites in the collection of the Palace Museum], vol. 1: Henan juan [Henan volume], Beijing, 2005, book 2, pls 445-7, but most of them probably deriving from the smaller ‘bubble bowls’.

While larger splashed Jun bowls exist, they tend to be of much lower quality overall, lacking the concise form of the present piece with its neat incurved rim as well as the striking colouration and are generally of later date, being products of the Yuan dynasty.

Due to its outstanding beauty, quality and rarity, this bowl has become known as the ‘Alexander Jun bowl’, after its first known collector in the West, William Cleverley Alexander (1840-1916). Alexander was a British banker, avid art collector and patron, and himself an accomplished water colourist. His father was a founding member of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. He was an early patron of the American painter James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), who when living in the UK was involved in the decoration of Alexander’s London residence, Aubrey House at Holland Park, and portrayed three of Alexander’s daughters. Two of these paintings, of Miss Cicely Alexander and Miss May Alexander, were donated to the Tate Gallery (Tate Britain), London, of which the former, titled Harmony in Grey and Green, became one of Whistler’s most celebrated paintings. Alexander was a founding member of the National Art Collections Fund in Britain, member of the Burlington Fine Arts Club and generously loaned pieces to exhibitions. Besides paintings, he collected in particular Chinese and Japanese works of art. The most famous piece of Alexander’s important Chinese collection, the ‘Alexander Bowl’, is one of the scarce extant examples from the Zhanggongxiang kilns of Ruzhou (Regina Krahl, “The ‘Alexander Bowl’ and the Question of Northern Guan Ware”, Orientations, November 1993, pp. 72-5). R.L. Hobson (Hobson, Rackham & King 1931, p. 3) honoured his collection with the words “The Alexander Collection has a special and almost romantic interest as one of the first of what we may call the modern type of Chinese collections … after assembling a goodly series of the later and more easily obtainable Chinese wares, he turned his attention to the forerunners of these, which were beginning to appear in some quantity in the European market”. Hobson devoted one of the few colour plates in this publication to the present bowl (fig. 3). Alexander bought this bowl in 1911 as a ‘claire-de-lune bowl with red spots’.

R L Hobson, Bernard Rackham & William King, Chinese ceramics in private collections, London, 1931, Col. pl. 2.

Sotheby's. Important Chinese Art including Jades from the De An Tang Collection and Gardens of Pleasure – Erotic Art from the Bertholet Collection, Hong Kong, 29 April 2022

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F57%2F78%2F119589%2F129759940_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F76%2F00%2F119589%2F129065442_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F99%2F10%2F119589%2F129064621_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F18%2F84%2F119589%2F129061143_o.jpg)