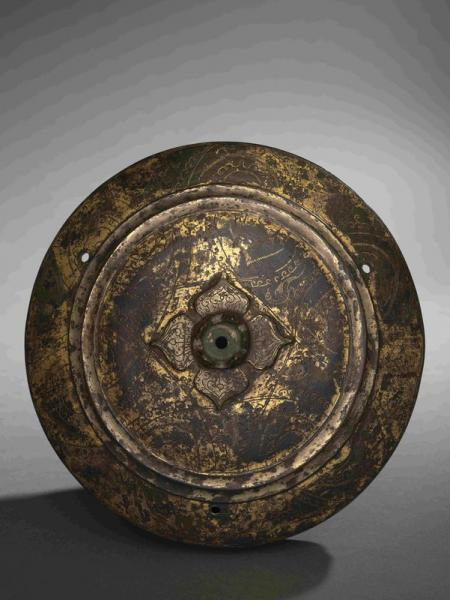

A very rare gilt-bronze incised 'hunting scene' tripod container and cover, lian, Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-9 AD)

Lot 215. A very rare gilt-bronze incised 'hunting scene' tripod container and cover, lian, Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-9 AD); 23.5cm (9 2/8in) diam. x 23.5cm (9 2/8in) high. (2). Estimate 30 000 € - 50 000 €. Photo Fabrice Gousset.

The cylindrical vessel raised on three kneeling bear supports, divided into registers by three bowstrings, variously decorated around the sides with an intricate incised designs of lappets and scrollwork with a scene of a man wielding a spear hunting a mythical beast, flanked with a pair of taotie-mask and ring handles, the cover with an external border decorated with a similar hunting scene, around the internal medallion with lappets alternating with six animals including an owl and a toad around a four lappets encircling an aperture.

Provenance: Robert Rousset, Paris (1901-1981), acquired prior to 1935

Jean-Pierre Rousset, Paris (1936-2021).

Note: Cast as a miniature 'mountain' decorated with spear-armed men hunting mythical beasts, the present vessel was once entirely gilt and thus particularly precious. Although the shape is probably inspired by ritual wine containers, zun, produced during the Warring States period (475-221 BC), the vessel could have been used also as a cosmetic box or in the ritual context, may have acted as a visual aid for the tomb occupant to envision the mythical Immortal land of Penglai which they were hoped to reach in their afterlife.

According to the Classic of Mountains and Seas, Shanhai Jing, likely compiled during the 4th century BC, Penglai was one of the Immortal islands located in the Eastern Bohai sea, which vanished from sight as voyagers glimpsed them and hoped to land on them in their search of Immortality-granting elixirs. These islands were defined by high mountains dotted with caves where Immortals were thought to live.

Based on the Daoist idea of a peaked island, the miniature landscape presented on this vessel may have represented the deceased's journey through a winding obstacle-laden landscape, in search of the elixir of eternal life. '(..) Having transcended sacred mountains, one will gain supernatural powers, controlling the wind and rain, and finally reach to Heaven, the Abode of the Celestial Emperor', mentions the 'Masters from Huainan', Huainanzi, in the 2nd century BC. See A.G.Wenley, 'The Question of the Po-Shan-Hsiang-Lu', in Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America, no.3, 1948, pp.5-12.

Mountains were highly regarded in China as primary components of the universe, because of their ability to produce water, the life-giving element, from the clouds swirling around them. They were linked with a profound interest in meeting the Immortal spirits inhabiting their naturally high peaks, which provided the closest connection with heaven. From at least the time of emperor Wudi (r.141-87 BC), the mountains located on the Immortal islands in the Eastern Sea were thought to be reached in two ways, wither during one's earthly lifespan, through the ingestion of magical potions, or following one's death, through the preservation of the body and soul in the burial. See J.Rawson, Mysteries of Ancient China: New Discoveries From the Early Dynasties, London, 1996, pp.172-173; see also S.Erickson, 'Boshanlu: Mountain Censer of the Western Han Period: A Typological and Iconographical Analysis', in Archives of Asian Art, 1992, vol.45, pp.6-28.

The animals populating the mythical mountain depicted on the present vessel were probably inspired by the mythical creatures inhabiting the wondrous realms described in the Shanghai Jing (Classic of Mountains and Seas), the Huainanzi, compiled sometime before 139 BC, and the Zhuangzi (Master Zhuang) of the late Warring States period (476-221 BC). It is also quite possible that the animals may have been inspired by those involved in the imperial hunts that were carefully staged in the royal parks during the Han dynasty. The Han emperors had an unprecedented passion for building brilliant parks of great size where the rulers staged symbolical conquests of the natural world through ritual hunts and animal combats. See E.H.Schafer, 'Hunting Parks and Animal Enclosures in ancient China', in Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 1968, vol.11, no.3, pp.318-343.

The taotie mask designs decorating the ring handles and the three bears shaping the feet were probably aimed at protecting the deceased against the evil influences they may encounter in their afterlife. Although the actual significance of the taotie motif is still the subjects of extensive academic research, it is mentioned in the 'Spring and Autumn Rituals' as bodiless monster swallowing hostile tribes. By the same token, the 'Classics of Mountains and Seas' praises the bear for its bravery and refers to the creature as the gate guardian of the mythical mountains invoked by Daoists. See D.Jenkins (et al.), Mysterious Spirits, Strange Beasts, Earthly Delights: Early Chinese Art from the Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Collection, Portland, 2005, pp.34-35.

Compare a closely related gilt openwork lian and cover, Han dynasty, in the Cleveland Museum of Art (Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund 1972.44); see also a related gilt and silver bronze example, Han dynasty, in the Minneapolis Institute of Art (acc.no.50.46.49a,b).

A related bronze un-gilt and plain lian and cover, Han dynasty, with tiger supports and ram finials, was sold at Sotheby's New York, 22 March 2011, lot 195.

From J.T. Tai & Co. An archaic bronze vessel and cover (lian), Han dynasty. Height: 8 ¾ inches. Sold at Sotheby's New York, 22 March 2011, lot 195. Courtesy Sotheby's

the deep cylindrical body raised on the three well articulated tiger-form feet and cast with three strapwork bands, taotie masks with pendent ring handles on either side, the fitted, domed cover with three recumbent rams enclosing a finely incised quatrefoil centered by a loop handle with loose ring, grayish-green patina with malachite and azurite encrustation (2)

Provenance: Yamanaka & Co, Inc., New York.

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Christian R. Holmes.

Parke-Bernet Galleries, Inc., New York, 14th November 1963, lot 263.

Literature: Christian R. Holmes Ancient Bronzes, New York, 1940, photographed by M. E. Hewitt.

Réalisé à l'image d'une montagne miniature et décoré d'hommes armés de lances chassant des animaux fabuleux, ce vase tripode était à l'origine entièrement doré et donc particulièrement précieux. Bien que sa forme soit probablement inspirée des récipients rituels à alcool de type zun, produits durant l'époque des Royaumes Combattants (475 – 221 av. J.-C.), ce récipient a aussi pu servir de boîte à cosmétiques ou, dans un contexte rituel, faire office de support visuel pour aider l'occupant de la tombe à imaginer l'île mythique des immortels Penglai, dans l'espoir d'atteindre l'au-delà.

Selon le Classique des Montagnes et des Mers, Shanhai Jing, sans doute compilé au IVe siècle av. J.-C., Penglai était une des îles des Immortels situées dans la mer orientale de Bohai, îles qui disparaissaient une fois aperçues par les voyageurs espérant y parvenir dans leur quête de l'élixir d'immortalité. Ces îles étaient formées de hautes montagnes parsemées de grottes où vivaient, pensait-on, les Immortels.

Basé sur l'idée taoïste d'une île formant un pic montagneux, le paysage miniature présenté sur ce récipient pourrait avoir représenté le voyage du défunt à travers un paysage sinueux plein d'obstacles, à la recherche de l'élixir d'immortalité. « (...) Après avoir dépassé les montagnes sacrées, on obtiendra des pouvoirs magiques, contrôlant le vent et la pluie, et on accèdera finalement au Ciel, « la Demeure de l'Empereur Céleste » dit le Huainanzi (Le Maître de Huainan) au IIe siècle av. J.-C. Voir A. G. Wenley, «The Question of the Po-Shan-Hsiang-Lu », dans Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America, n°3, 1948, pp.5-12.

Les montagnes étaient considérées avec un grand respect, en Chine, en tant qu'éléments primordiaux de l'univers, en raison de leur capacité à produire de l'eau, l'élément donnant la vie, depuis les nuages tourbillonnant autour d'elles. Elles étaient associées au désir profond de rencontrer les immortels habitants ces hautes cimes naturelles qui offraient le lien la plus proche avec le Ciel. Depuis au moins l'époque de l'empereur Wudi (r. 141-87 av. J.-C.), les montagnes des Îles des Immortels dans la Mer de l'Est pouvaient, pensait-on, être atteintes de deux façons : soit durant la vie terrestre, par l'ingestion de potions magiques, soit après la mort, par la préservation du corps et de l'âme dans la tombe. Voir J. Rawson, Mysteries of Ancient China : New Discoveries From the Early Dynasties, London, 1996, pp. 172-173 ; voir aussi S. Erickson, « Boshanlu : Mountain Censer of the Western Han Period : a Typological and Iconographical Analysis », dans Archives in Asian Art, 1992, vol.45, pp.6-28.

Les animaux peuplant la montagne légendaire représentés sur ce bronze ont probablement été inspirés des créatures fantastiques habitant les royaumes merveilleux décrits dans le Shanhai Jing, le Huainanzi (compilé avant 139 av. J.-C.).) et le Zhuangzi (Maître Zhuang) de la fin des Royaumes Combattants (476-221 av. J.-C.). Ces animaux auraient aussi pu être inspirés de ceux associés aux chasses impériales et mis en scène avec soin dans les parcs royaux durant la dynastie Han. Les empereurs Han avaient une passion sans précédent pour la construction de parcs immenses et magnifiques où était mise en scène la conquête symbolique du monde naturel par l'organisation de chasses rituelles et de combats d'animaux. Voir E. Schafer, « Hunting Parks and animal Enclosures in Ancient China », dans Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 1968, vol.11, n°3, pp.318-343.

Les motifs de masques taotie décorant les anses en anneaux et les trois ours formant les pieds visaient probablement à protéger le défunt contre les esprits néfastes qu'ils pourraient rencontrer dans l'au-delà. Bien que la signification du motif de taotie soit encore un vaste sujet de recherches universitaires, il est décrit dans les Annales des Printemps et Automnes comme un monstre sans corps dévorant les tribus hostiles. De la même façon, le Classique des Montagnes et des Mers loue la bravoure de l'ours et désigne l'animal comme le gardien de la porte menant aux montagnes légendaires évoquées par les taoïstes. Voir D. Jenkins (et al.), Mysterious Spirits, Strange Beasts, Earthly Delights : Early Chinese Art from the Arlene and Harold Schitzer Collection, Portland, 2005, pp. 34-35.

Voir un lian couvert ajouré et doré très comparable, dynastie Han, au Cleveland Museum of Art (Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund 1972.44) ; et voir un exemple comparable en bronze argenté et doré, dynastie Han, au Minneapolis Institute of Art (acc.no.50.46.49a, b).

Un lian couvert comparable, sans dorure ni décor, dynastie Han, avec des pieds en forme de tigre et des béliers en ronde-bosse sur le couvercle, a été vendu chez Sotheby's New York, le 22 mars 2011, lot 195.

Bonhams Cornette de Saint Cyr Paris. The Robert and Jean-Pierre Rousset Collection of Asian Art: A Century of Collecting - Part 2. Paris, 26 october 2022

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240303%2Fob_3525eb_801-1.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F45%2F10%2F119589%2F129777700_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F45%2F89%2F119589%2F129766046_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F52%2F01%2F119589%2F129765624_o.jpg)