'Labyrinth: Knossos, Myth & Reality' at Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Replica of bull’s head fresco from the North Entrance of the palace of Knossos, early 20th century, painted plaster, 88 x 136 cm ©Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

OXFORD - The Ashmolean’s first exhibition in 2023 explores one of the most infamous of classical myths and celebrated stories of modern archaeology: the Labyrinth, the Minotaur and the Palace of Knossos. The exhibition features more than 200 objects, over 100 of which are on loan from Athens and Crete. They will be shown, for the first time in more than a century, alongside the Ashmolean’s unrivalled collections and the archive of photographs and documents that illustrate the exciting moments when the Palace of Knossos was uncovered between 1900–1905.

In Greek myth the Labyrinth at Knossos held the Minotaur, a monstrous bull-human hybrid awaiting his sacrificial victims. The story remains one of the most enduring of classical myths and, unsurprisingly, Knossos is now one of the most visited archaeological sites in Greece.

Ancient silver coin from Knossos showing the Labyrinth, c. 300-270 BCE; diameter 26 mm; weight 10.8 g, Knossos © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

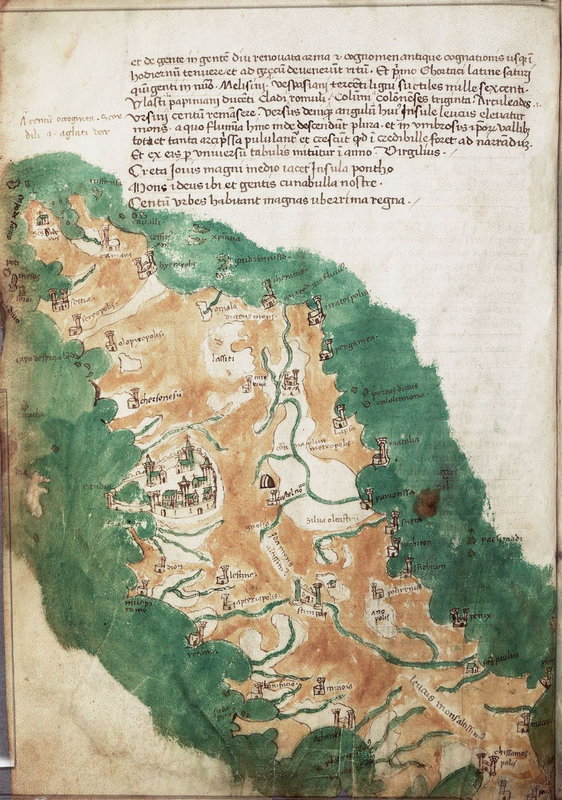

The exhibition traces the story of the excavation of Knossos at Crete. For centuries, travellers searched the island for the mythical Labyrinth, leaving a trail of myths, misleading maps, and misread archaeological evidence until 1878 when the remains of an ancient building at Knossos were discovered by a Cretan businessman and scholar, Minos Kalokairinos. Local authorities prevented him from properly excavating the site as Crete was under the partial control of the Ottoman Empire, and until it gained independence, any significant finds were at risk of being removed to Constantinople (Istanbul). Kalokairinos’s discoveries attracted international attention, and archaeologists from various countries competed for the future rights to excavate. In 1900, it was the British archaeologist and Keeper (director) of the Ashmolean, Sir Arthur Evans (1851–1841), who was granted permission to dig by the Cretan authorities.

Evans began his excavation, convinced that this building was the Labyrinth of myth. He rapidly found colourful frescoes, clay tablets showing an early system of writing and even a room with an intact stone throne on which he imagined the rulers sat. He referred to this labyrinthine building as the ‘Palace of Minos,’ and he was able to establish that it was around 4,000 years old and built during the Bronze Age. He popularised the term ‘Minoan’ to describe the civilisation of Crete in this period.

Sir Arthur Evans at the Palace of Knossos, 1901 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The exhibition features some of the finest Minoan objects that Evans uncovered, from everyday objects like decorated pottery to elaborate sculptures, many on loan from the Heraklion Archaeological Museum. They are reunited with drawings made during the excavation from the Ashmolean’s Sir Arthur Evans archive. Some of the drawings show the process of reconstructing the site and its finds, providing an insight into Evans’s controversial concrete restorations of the Palace of Minos in the mid-20th century.

One of the exhibition’s highlights is a finely carved marble triton shell, showing the skill of Minoan craftspeople and their particular interest in marine animals. Other objects show octopuses and Argonauts in the depths of the sea, or depictions of bulls, sometimes with people leaping over them. Evans saw in these the origin of the myth of the Minotaur: some Minoan seal-stones show how these images of bull-leaping could be condensed into the head of a bull and the legs of the leaper.

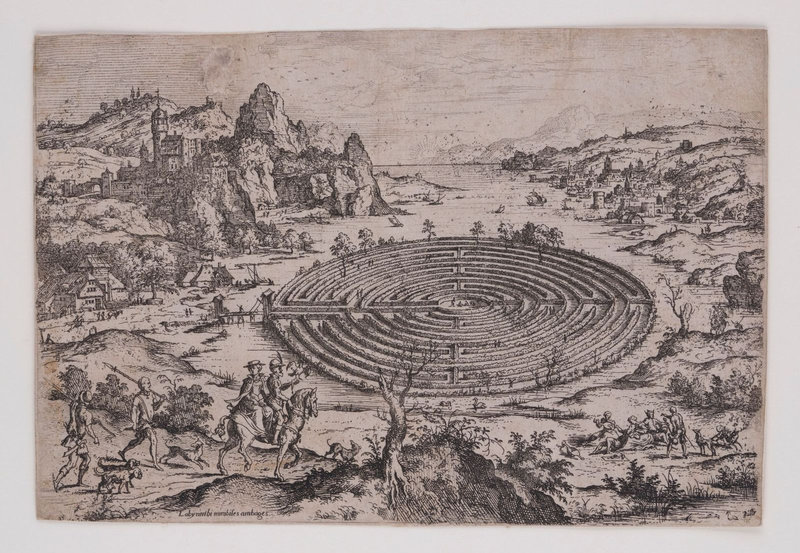

Hieronymus Cock (1518–1570) after Matthijs Cock, The Cretan Labyrinth, c.1558, etching on laid paper, 22.1 x 29.9 cm © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The exhibition also offers two immersive experiences inspired by Knossos. A RESTORATION (2016) by Turner Prize winning artist Elizabeth Price will be shown in the third gallery. The 15-minute, two-screen digital video is a fiction, narrated by a ‘chorus’ of ‘museum administrators’ who use Arthur Evans’s archive to figuratively reconstruct the Palace at Knossos within the museum’s computer server. They imagine its intricate space as a virtual chamber through which a range of artefacts digitally flow, clatter and cascade. In the second gallery, visitors are taken on a unique virtual tour of the Knossos Palace as reimagined in the 5th century BCE, during the time of the Peloponnesian War, thanks to the digital recreation of the site in the Assassin’s Creed Odyssey video game. Ubisoft created the film specially for the exhibition to demonstrate the research behind the game.

The size and scale of the site meant excavation work at Knossos continued at times throughout the 20th century and still continues today. The final room of the exhibition displays discoveries made in the post-war period, and many recent finds. These include objects verifying Knossos as the site of the earliest known farming settlement in Europe, established in around 7000 BCE, as well as incredible objects uncovered in cemeteries and religious sanctuaries in the surrounding areas, showing that Knossos flourished for thousands of years before it was largely abandoned in around 800 BCE. Among the recent finds on display is a spectacular Bronze Age dagger with inlaid gold and silver griffins, the first of its kind found on Crete. The exhibition ends with the chilling discovery, made in 1979, that appeared to show evidence of a ritual human sacrifice – challenging public perception of the Minoans as peaceful and providing a tantalizing hint of the Minotaur myth.

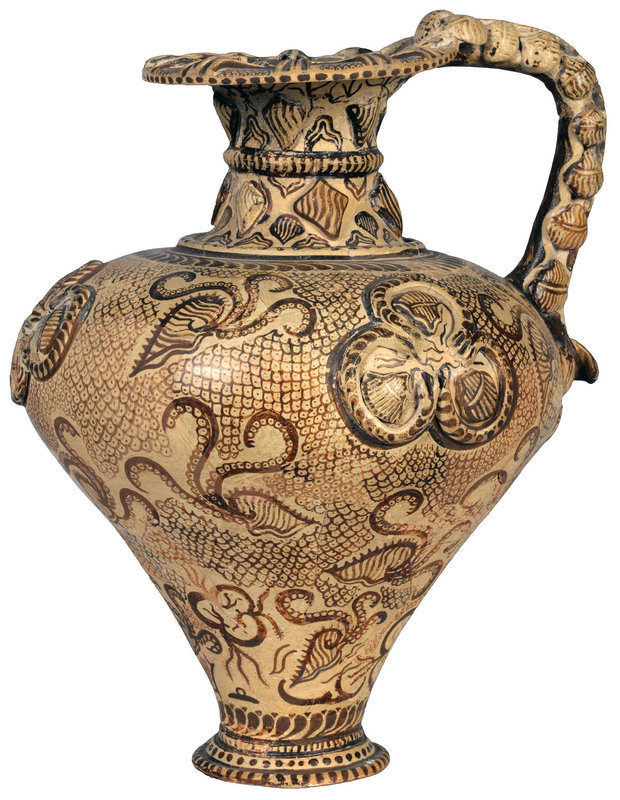

The Poros Ewer,1500–1450 BCE, ceramic, h. 26.2 cm, Poros © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage,Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

Dr Xa Sturgis, Director of the Ashmolean, says: 'This is an exhibition that only the Ashmolean could mount. Since 1903, the Museum has held the largest and most significant collection of Minoan archaeology outside Crete thanks to one of my predecessors as Ashmolean Director, Sir Arthur Evans.

‘Long thought of as an archaeological pioneer, Evans and his interventions at Knossos are now being reconsidered in their historical context. The exhibition offers both an exploration of Minoan culture and Greek myth, and a deeper look at British archaeological history.’

10 February–30 July 2023

Damares Cup, (Middle Minoan IIA ‘eggshell ware’ cup), 1800–1750 BCE, ceramic, h. 8.4 cm, Knossos Palace: Royal Pottery Stores © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Finger ring with design showing bull-leaping, 1450–1375 BCE, gold, l. 2.5 cm, said to be from Archanes © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Emile Gillieronpère (1850–1924), Restoration of Ladies in Blue Fresco, undated, watercolour, 95 x 161 cm ©Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Sculpture of the Minotaur, 1–300 CE, marble, h. 73 cm, Athens © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage,National ArchaeologicalMuseum

Bull’s head rhyton, 1450–1375 BCE, ceramic, 20.2 x 11.3 cm, Knossos: Little Palace © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage,Heraklion ArchaeologicalMuseum

Carved stone vessel in the shape of a triton shell, 1600–1450 BCE, limestone, h. 31.7 cm, Knossos Palace: Central Treasury © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

Aryballos in the shape of a cockerel, 670–600 BCE, ceramic, h. 15.5 cm, Knossos North Cemetery: Tomb 40 © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Figurine of goddess with upraised arms, 1375–1300 BCE, ceramic, h. 22 cm, Knossos Palace: Shrine of the Double Axes © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

Fragment of fresco with labyrinth design,1700–1600 BCE, paintedplaster, 21.5x20 cm, Knossos Palace: Corridor of the Labyrinth Fresco © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Fragment of stone rhyton with octopus tentacles in relief, 1600–1450 BCE, limestone, h. 18 cm, Knossos Palace: Central Treasury © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Bird-shaped perfume vessel, 1–100 CE, glass, l. 17.5 cm, Knossos North Cemetery: Venizeleion site, Tomb 197 © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Ephorate of Antiquities of Heraklion

Dagger with inlaid griffin, 1450–1375 BCE, bronze, ivory, gold, silver, 40 cmx5 cm, Knossos: Anetaki Plot © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Ephorate of Antiquities of Heraklion

Marble head of Zeus, 1–300 CE, marble, 21 x 15 cm, Knossos: Anetaki Plot © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Ephorate of Antiquities of Heraklion

Cristoforo Buondelmonti, Map of Crete from Tractatus Insulari Archipelagi, c.1420, vellum, 25 x 18 cm © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Mark Wallinger (b. 1959), Labyrinth #232 Green Park, 2013. Vitreous enamel on steel plate, powder coated black frame, 63.5 x 63.5 cm © Mark Wallinger. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Thierry Bal

Video still from Assassin’s Creed Odyssey © Assassin’s Creed™ & © Ubisoft Entertainment. All Rights Reserved.

The Minotaur, concept art by Guang Yu Tan, 2018 © Assassin's Creed™ & Ubisoft Entertainment. All rights reserved.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_dcd32f_telechargement-32.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_0d4ec9_telechargement-27.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_fa9acd_telechargement-23.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_9bd94f_440340918-1658263111610368-58180761217.jpg)