A Chinese Imperial Ormolu Quarter-Striking Table Clock, Palace Clock Workshops, Qianlong Period (1736-95)

Lot 41. A Chinese Imperial Ormolu Quarter-Striking Table Clock, Palace Clock Workshops, Qianlong Period (1736-95); 55.2 cm high; 23.8 cm wide; 24.1 cm deep. Price realised GBP 428,400 (Estimate GBP 300,000 – GBP 500,000). © Christie's Image Ltd 2023

CASE: the case of rectangular outline, modelled overall with a profusion of lotus flowerheads and trailing foliage in high relief, the tiered cupola with spherical ribbed finial and pierced openwork lotus flower and leaf banding with arcaded gallery below, trellis balustrade between the conforming spires to the angles, the body with three-quarter part-baluster columns, hinged side panels and rear panel, the front glazed, on a later giltwood plinth with foliate gilt-lacquer band, raised on four bun feet to the angles

DIAL: the dial plate with 5 1/2 inch silvered chapter ring, Roman hours and Arabic five minutes, fleur-de-lis half-hour markers, four character signature plaque to the upper centre, pierced hour and minute hands

MOVEMENT: the three-train chain fusee movement with verge escapement housed within three plates, each joined by six pillars, the strike and quarter train within the front section, the going train in the rear, ‘ting-tang’ quarter striking on two bells and striking the hour on a larger bell

Provenance: Christie’s, London, 7 June 1993, lot 142.

CLOCKS AS TRADE GIFTS

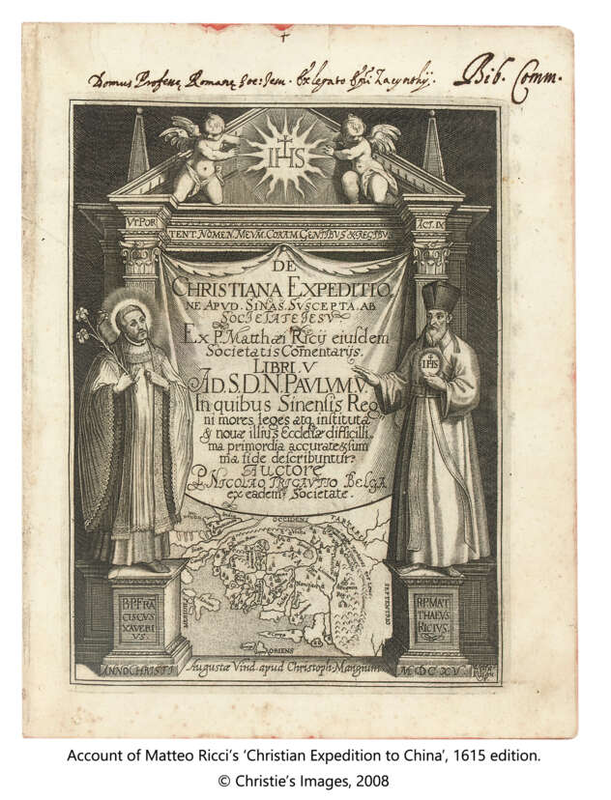

This magnificent Chinese Imperial clock, made in the Palace workshops, was the culmination of over two hundred years of trade in horological masterpieces between China and the West. The pioneering Jesuit missionaries such as Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) and Michele Ruggieri (1543-1607) of the late 16th century embedded themselves in Chinese culture as a means to establish Christianity. (M. Ricci, China in the Sixteenth Century: Journals of Matteo Ricci, 1583-1610, New York, 1953). Through mastering the language, winning favour with Chinese gentry and officials was sought by presenting Western novelties as gifts to arouse interest and gain trust. Clocks and watches formed the most significant part of these gifts and their importance was fundamental in gaining influence with Chinese officials.

Ruggieri writing in 1580 to the headquarters of the Society of Jesuits in Rome stated ‘It would be most desirable if your Holiness would send some large ornate clocks as gifts. An hour-striking, sonorous clock designed for the palace setting would be needed for the purpose. In addition, I also require one small hour-striking clock that can be hung from a ring and held in the palm, such as the one Cardinal Fulvio Orsini presented to your Holiness the year I departed Rome, or anything of the like’. Later in the same year Ruggieri accompanied some Portuguese traders on a visit to Guangzhou, gaining favour with his gifts; ‘A military official was especially friendly and more than willing to introduce me to the Court. Our acquaintance was built on a clock I gave him when we first met’. Rici gradually established his mission on the mainland and became a highly respected figure amongst Chinese scholars but access to the Emperor himself was the key aim.

In 1600 Ricci presented two clocks to Emperor Wanli (reign 1572-1620) who appointed four eunuchs from the Imperial Board of Astronomy to study horology with Ricci. Emperor Wanli’s fascination with the clocks enabled Ricci to establish more influence within the Chinese Court and he effectively established himself as the unofficial clockmaker to the Imperial palace. This in turn led to a proliferation of Western clocks and watches throughout the Court and with subsequent Emperors.

CHINESE CLOCKMAKING

During the Kangxi reign (1662-1722) Guangzhou became a focal point for trade between China and the West and established itself as an important clockmaking centre. Clocks from Guangzhou typically followed Western styles and interpretation of Chinese architecture and ornament, mostly with brightly coloured enamels, particularly blue, a proliferation of automatons and musical functions. The Guangzhou clocks were generally hybrids of Chinese and Western aesthetics. Canton was another clockmaking centre and here too clock cases were made copying Western studies of Chinese architecture (C. Pagani, Eastern Magnificence and European Ingenuity, University of Michigan, 2001, pp. 152-170).

IMPERIAL PALACE WORKSHOPS

The Imperial Palace clock workshops, or Zuozhongchu, produced clocks and watches from the late seventeenth century under the guidance of the Kangxi Emperor. As Catherine Pagani discusses (Pagani, 2001, op. cit. p. 162.) these clocks, as with the present clock, show much stronger ties to Chinese art and architecture than the clocks made in Guangzhou, the pagoda tiers and roofs being accurately modelled. Typified by a much more restrained design overall, there is less use of coloured stones and automaton work, reflecting the Emperor's complaints some some of the clocks he had received were 'ill-conceived in form and style'. The refined rectangular form of this clock with its pierced stepped and arcaded top recalls South German Augsburg table clocks of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries pre-dating the more elaborate eighteenth century designs of the London makers. Local hardwoods such as Zitan were used for the case construction. Interestingly the base of the present clock is lacquered wood and it may well originally have had a more elaborate wooden plinth or been part of a larger structure. A very similar three-train table clock is in the Palace Museum Collection, with ormolu plinth and feet (Lu Yangzhen (editor), Timepieces Collected by the Qing Emperors in the Palace Museum, Hong Kong, 1995, p. 40). The flowers and foliage are typically Chinese as is the balustrade design whilst the clock dial retains the usual European style silvered chapter ring. The movement uses three plates, rather than two, to house the motionwork, this is unusual and not typically European in style but the fusees, chains and verge escapement are in the English manner whilst the vertical hammers are very much in the French manner of the late 17th / early 18th century period. As with the majority of Palace made clocks it has the engraved silvered plaque to the dial bearing the four character mark ‘Made in the year of Qianlong’.

Christie's. The Exceptional Sale, London, 06 July 2023

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F71%2F95%2F119589%2F126132023_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F01%2F98%2F119589%2F122318520_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240509%2Fob_046060_telechargement-3.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240509%2Fob_d81be2_telechargement.jpg)