'Transformation: Modern Japanese Art' showcases major gift from philanthropist Terry Welch

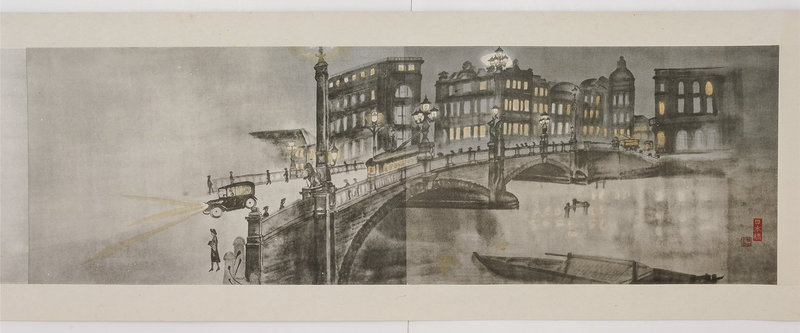

Ōtani Son’yu (1886–1939), Iguchi Kashū (1880–1930), Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, Japan, 1922. One of a set of eight handscrolls woodblock–printed over collotype; ink and color on paper. Purchase, Richard Lane Collection, 2003 (2008.0035.1). The Honolulu Museum of Art.

HONOLULU, HAWAII.- Celebrating a recent donation of 127 artworks by noted collector Terry Welch, the Honolulu Museum of Art presents Transformation: Modern Japanese Art. The exhibition features paintings, ceramics and lacquerware produced between the 1860s and 1930s, a dynamic yet often overlooked chapter in Japanese art history.

“We are honored that Mr. Welch entrusted HoMA with his important collection,” said HoMA Director Halona Norton-Westbrook. “This monumental gift shines a light on a period of profound social change and artistic innovation, and it further enriches the museum’s noteworthy collection of modern Japanese art. We look forward to sharing these works with our community and offering visitors a glimpse into Japan’s past through these stunning creations.”

Amidst political, economic and social influences from other countries, Japanese art underwent a remarkable metamorphosis during the modern period. A period of diplomatic isolationism lasting over 200 years came to an end, and as the nation became part of an international community, the Japanese government expressed a new sense of cultural enlightenment by establishing public art schools and sponsoring national art exhibitions.

While promoting Nihonga (literally “Japanese painting”), a revival of classical art techniques as a contemporary and national style, painters collaborated with specialists in ceramics and lacquer and other media to develop an innovative, interdisciplinary aesthetic. Transformation explores the wide range of individuals responsible for these achievements, from pioneers of the county’s new art education system to superstars of national exhibitions and independent eccentrics.

“Artists rediscovered the past and used its bedrock to build a road to the future,” explains Curator of Asian Art Shawn Eichman, who curated the exhibition. “Art of this era has its own distinct character, encompassing new ways of thinking while respecting tradition. HoMA’s strengths in Japanese art from the late 19th and early 20th centuries make the museum uniquely situated to present an exhibition on this exciting subject.”

Taniguchi Kōkyō (1864–1915), Kikuchi Hōbun (1862–1918), Tsuji Kakō (1870–1931), Yamamoto Shunkyo (1871–1933). Two Painted Lacquer Plates, Japan, c. 1910. Lacquer on wood. Gift of Terry Welch, 2021 (2021-03-011). The Honolulu Museum of Art.

As the curriculum of art schools expanded to include subjects such as ceramics in response to an ever-widening conception of the arts, both professors and students experimented in different media, and collaborated on projects.

The four artists who decorated these lacquer plates were all leading early professors of painting at the Kyoto Prefecture Painting School, and well-established artists with independent careers. Examples of collaboration between the school’s professors, especially in materials other than those for which they were primarily known, are rare and little-studied, but probably were common in the experimental environment of the early 20th century.

Takeuchi Seihō (1864–1942), Monkey in Plum Blossoms, Japan, c. 1910. Stoneware. Gift of Terry Welch, 2021 (2021-03-005). The Honolulu Museum of Art

Seihō became a professor of painting at the Kyoto School of Arts and Crafts shortly before this bowl was likely made. By this time, he had already traveled to Europe for the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900. During his trip he visited the Dresden Zoo, and upon returning to Japan he became known for his highly realistic depictions of animals. Here, though, Seihō rather draws from the classical East Asian literati tradition for both his subject—plum blossoms—and his technique, with a charming monkey loosely brushed in expressive ink.

The Kyoto Prefecture Painting School changed its name to Kyoto School of Arts and Crafts in 1894, reflecting an expanded curriculum that included crafts such as ceramics as well as painting. This brought the school’s painting professors into close contact with artists working in other media, evident in this exhibition not only in Seihō’s design on this bowl (which would have been shaped, glazed, and fired by an unknown ceramicist), but also in Suzuki Shōnen’s Nine Flaming Jewels, and in Five Painted Lacquer Plates designed by four professors at the school.

Suzuki Shōnen (1849–1918), Nine Flaming Jewels, Japan, late 19th–early 20th century. Porcelain. Gift of Terry Welch, 2021 (2021-03-003). The Honolulu Museum of Art.

Flaming jewels were traditional symbols of Buddhist enlightenment and became a popular subject in Japanese ink painting. Although there are only five cups in this set, some have multiple jewels, resulting in nine total (nine being an auspicious number in Buddhism). Shōnen was a professor at the Kyoto Prefecture Painting School (later Kyoto School of Arts and Crafts), as well as a famous painter from a well-established traditional family lineage.

Shōnen probably only painted the designs on the cups; their shaping, glazing, firing, etc. were done by an unknown ceramic specialist. Kyoto ceramics are well known for their brightly colored glazes, a tradition dating back to the Edo period (1615–1868). At the same time, before the modern period only stoneware was made in Kyoto, and porcelain such as this was a new development.

Kawakita Kaho (1875–1940), Prince Ōtōnomiya Escaping to Kumano, Japan, c. 1900–1912. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk. Gift of Terry Welch, 2021 (2021-03-023). The Honolulu Museum of Art.

Historical subjects played an important role in the canon of modern Japanese painting, following precedents of other national styles in Europe, and a long tradition of historical painting narratives in Japan. Historical subjects featured prominently in the annual national exhibition, in which Kaho thrived, eventually being appointed a juror.

Prince Ōtōnomiya (1308–1335), seen here traveling deep in the mountains with a military cadre, was a key figure in the fall of the Kamakura shogunate (1185–1333). Ōtōnomiya was the head abbot of an influential Buddhist temple. When his father, the emperor Go-Daigo (1288–1339), challenged the shogunate, Ōtōnomiya left the temple and made his way to Kumano—the scene shown here—where he raised troops to support his father. Eventually, they convinced the powerful warlord Ashikaga Takauji (1305–1358) to join them, and for a brief period Go-Daigo was restored to power.

However, when Go-Daigo overlooked Takauji in favor of Ōtōnomiya and the other princes, Takauji fabricated charges against Ōtōnomiya and had him beheaded; Ōtōnomiya was only twenty-seven years old. Takauji would go on to establish the Ashikaga shogunate (1336–1573), and it would not be until 1868 that an emperor was once again restored to power.

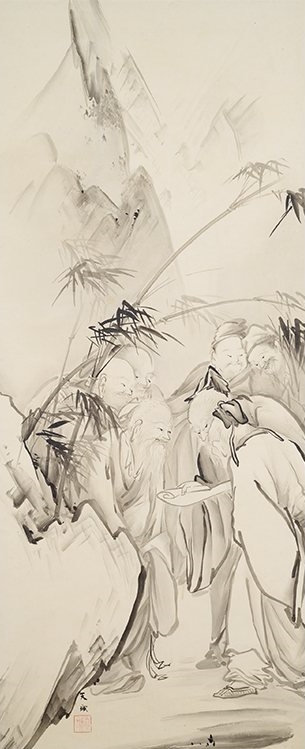

Honda Tenjō (1867–1946), Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, Japan, c. 1910s–1920s. Hanging scroll; ink on paper. Gift of Terry Welch, 2021 (2021-03-101). The Honolulu Museum of Art.

The Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove were a group of historical figures who lived in China during the 3rd century CE. The political climate was especially dangerous at the time, and they became known for their avoidance of government service and their pursuit instead of leisurely reclusion, writing poetry, playing music, and especially drinking alcohol together in a bamboo grove near one of their homes. They were one of the prototypes of the lofty scholar who practices self–cultivation and moral integrity instead of serving a corrupt ruler. They were celebrated in early literature, and within two centuries of their lifetimes they were already depicted in the arts.

Honda Tenjō was a key figure in the Tokyo art world during the early 20th century. He was one of the most prominent students of Kanō Hōgai (1828–1888), who played an important role in the early modernization of traditional Japanese painting. Following his teacher, Tenjō’s work has its foundation in traditional Kanō School brush techniques, such as the “axe-cut” strokes that texture the rocks and the deftly executed bamboo leaves, but these are dramatically transformed through an emphasis on contrasting light that conveys a sense of volume inspired by Western drawing.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240508%2Fob_d997ec_d21e3e110569bdfa219529297300e28a-1402x.png)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240508%2Fob_4c468b_telechargement-4.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240508%2Fob_7c1cc0_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240507%2Fob_6e4c73_telechargement-17.jpg)