'Lineages: Korean Art' at The Met, through October 20 The Met Fifth Avenue

NEW YORK - Since November 7, 2023, The Metropolitan Museum of Art presents the exhibition Lineages: Korean Art at The Met, which celebrates the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Museum’s Arts of Korea gallery. The exhibition will showcase 30 objects dating from the 12th century to the present day, including works acquired by the Museum in the last 25 years, paired with important international loans of 20th-century art. Some of the objects will rotate during the run of the exhibition. Through four themes—lines, things, places, and people—the exhibition will display the history of Korean art in broad strokes.

The exhibition is made possible by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Korea (MCST).

Max Hollein, The Met’s Marina Kellen French Director and CEO, stated: “This remarkably beautiful exhibition is both a celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Arts of Korea gallery, and an opportunity to reflect on the importance of presenting Korean art for The Met’s international audiences. By pairing historical with modern and contemporary artwork, the show also poses the question of how new lineages and legacies have been shaped by Korean artists responding to the past, their present, and looking toward the future.”

The first works of Korean art to enter The Met collection were eight musical instruments—part of the monumental gift of the Crosby Brown Collection in 1889. Four years later, in 1893, a mid-15th-century buncheong dish decorated with stamp-impressed chrysanthemums and dots in white slip was acquired by the Museum through a gift of 245 Asian ceramics from the Hudson River School painter Samuel Colman and his wife, Ann Lawrence Colman (née Dunham). The Met’s collection of Korean art grew steadily with the addition of some of the rarest objects, such as a 12th-century inlaid lacquer box and five prized Goryeo-dynasty (918–1392) Buddhist paintings, acquired between 1913 and 1930.

The Met signaled its commitment to the study of Korean art with the establishment of its first permanent gallery dedicated to the subject in 1998. New art forms and topics, such as buncheong, the Diamond Mountains, and the Silla dynasty (57 BCE–935 CE) were introduced to a global audience through pioneering exhibitions and publications.

Eleanor Soo-ah Hyun, Korea Foundation and Samsung Foundation of Culture Associate Curator of Korean Art at The Met, said: “The significance of the Arts of Korea gallery cannot be overstated. The gallery provides a platform not only to showcase Korean art through groundbreaking exhibitions but also to develop and increase the presence of Korean art and culture in The Met through acquisitions and public programming. In featuring modern Korean art in this exhibition, The Met is highlighting areas to develop and future pathways to pursue.”

Exhibition Overview

Lineages: Korean Art at The Met opens with the ink painting People by Suh Se Ok (1929–2020). A complex image formed by repeating the character for “human,” People is a captivating landscape of many people that encapsulates the exhibition’s four intertwined thematic sections: Lines, Things, Places, and People. The first theme, Lines, traces the importance of calligraphy and ink painting in Korean art and the multiple and divergent responses of modern artists to its significance and legacies.

Suh Se Ok (Korean, 1929–2020), People, 1988. Ink on danji (mulberry paper), 187 × 187 cm (painting). Courtesy of the Artist and MMCA; Gift of the Artist, 2014.

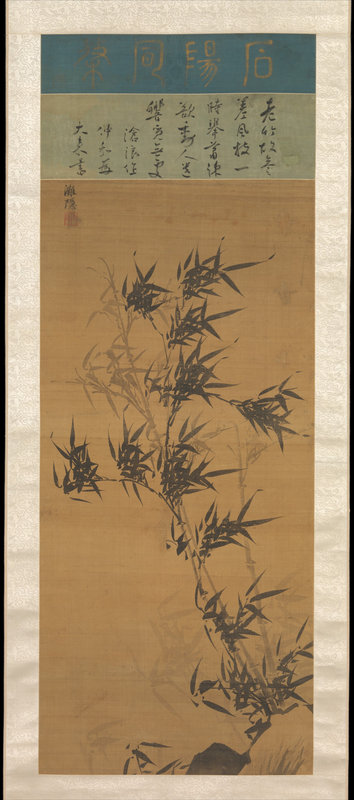

Yi Jeong (artist name: Taneun) (Korean, 1541–1626), Bamboo in the Wind, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), early 17th century. Hanging scroll; ink on silk with gold on colophon. Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015 (2015.300.299). © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A great-great-grandson of King Sejong (r. 1418–50), whose reign saw a cultural flowering and the invention of hangeul (the Korean alphabet), the prominent literati artist Yi Jeong gained renown for his poetry, calligraphy, and ink paintings. His calligraphic brushwork showcases intricate techniques, seen here in the nuanced shifts and precise strokes that form the leaves’ tapered tips and bent edges. The layered bamboo in skillfully contrasted dark and light ink tones creates a sense of spatial depth. Representing Confucian and Daoist values of integrity and nobility, bamboo was cherished by East Asian scholar-painters for centuries. Bending but not breaking in the wind, bamboo embodies resilience and fortitude, traits referenced in the inscription:

Aged bamboo has grown unevenly

Branches lift together in the breeze,

Desolate and sparse, seeking to stir people,

Lingering response found nowhere else.

—Translation by Tim Zhang

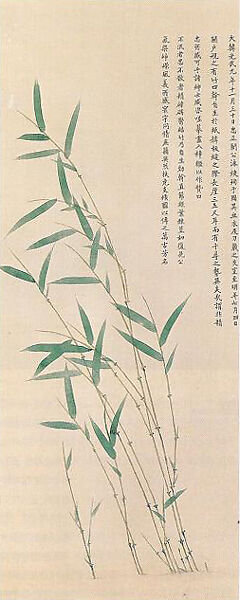

Attributed to Yang Gi-hun (artist name: Seokyeon) (Korean, born 1843–?), Blood Bamboo, 1906, Daehan Jeguk (Korean Empire, 1897–1910). Hanging scroll: ink and color on silk. Lent by Korea University Museum, Seoul.

Bamboo’s long-standing association with integrity and perseverance attains deeper significance in this work made against the turbulent backdrop of the Korean Empire. The title alludes to events following the Eulsa Treaty (1905) that stripped Korea of diplomatic autonomy, making it a protectorate of Japan. After the Korean politician Min Young-hwan (1861–1905), who ardently opposed the treaty, died by suicide, bamboo shoots reportedly grew through the floorboards under his blood-stained clothes. Bearing forty-five leaves, echoing Min’s age, and believed to have been nurtured by his blood, the plant was christened hyeoljuk, or “blood bamboo.”

The Korean Daily News (Daehan maeil sinbo) commissioned a painting on the theme from Yang Gi-hun, published on July 17, 1906, that inspired additional versions. This example, with its vital and rooted plant against an unadorned backdrop, stands as a powerful statement of incorruptibility and resistance.

Gathering of government officials, Unidentified artist, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), ca. 1551. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; 129.5 x 67.9 cm (image). Purchase, Acquisitions Fund, and The Vincent Astor Foundation and Hahn Kwang Ho Gifts, 2008, 2008.55. © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Yun Hyong-keun (Korean, 1928–2007), Umber Blue, 1975. Oil on linen, 130 × 96.5 cm. Courtesy of the Artist and MMCA; Gift of the Artist, 1982

While engaging with the techniques of calligraphy and ink painting, Yun Hyong-keun created works in oil that look as if one has zoomed in to see the interactions between paint and surface. He deliberately avoided black, a signifier of ink; instead, as his titles reveal, he layered brown umber and ultramarine blue to create degrees of darkness. Using different mixtures of paint and turpentine that would spread and soak at varying speeds, Yun made art that visualizes time and embraces chance. Absorption and application play equal roles, challenging the supremacy of mark making linked to ink painting and calligraphy. While the unpainted surface is centered, ideas about emptiness or the void—concepts that often conjure “Asian” spirituality or philosophy for non-Asian audiences—are countered by thin painted strips at top and bottom that give it a discrete shape.

Lee Ufan (Korean, born 1936), From Line, 1979. Oil on canvas, 193.5 × 259 cm. Courtesy of Lee Ufan Estate. Image courtesy of Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul.

Lee Ufan adeptly channels the dynamic precision of calligraphic strokes in his abstract art. His disciplined approach is evident in the straight lines of uniform width and spacing. The artist intentionally applied the calligraphic convention of gradually fading pigment, yet deliberately distances himself from ink painting lineages by selecting a blue cobalt-cadmium pigment. Like the other artists in this exhibition, Lee confronts the categorical divisions imposed on Korean artists and their creations by melding diverse materials, objects, and concepts. From Line exemplifies this, with its painted lines both solid and porous, the canvas both full and empty. Embracing the both-and paradigm, Lee’s title emphasizes “from” as much as “line,” suggesting a beginning and an ongoing process, and evoking openness rather than finality.

Kwon Young-woo (Korean, 1926–2013). Untitled, 1984. Ink and gouache on hanji (Korean paper), 224 x 170 cm. Courtesy of Kwon Young-woo Estate. Image courtesy of Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul.

Trained as an ink painter and part of Munghimhoe (묵림회, Ink Forest Group), Kwon Young-woo made works that disrupt mark-making and gestural abstraction norms. In the 1960s he began exploring the three-dimensional transformation of hanji (“Korean paper”)—confronting the elevated status of painting and the strict division between painting and sculpture. Traditionally, paper was revered as support for ink, but Kwon tore, pasted, and molded it, thrusting it to the forefront.

Working in Paris in the 1980s, Kwon reintroduced ink and color while still emphasizing the paper. Here, gray-blue radiates from the center, darkening vertical slashes as if by capillary action—yet the darkest “line” is a torn horizontal gap. Kwon applied color on the reverse, letting it seep through to the front, a challenge to the glamorized act of paint application.

The exhibition continues with Things, which examines the connection between historical and contemporary Korean art through objects. Historically, Korean ceramics have received the greatest attention in the West and comprise the bulk of collections in most Western museums. The Korean collection at The Met follows this trend. In this theme, ceramics are paired with modern and contemporary works—ranging from Kim Whanki’s Moon and Jar to Byron Kim’s Goryeo Green Glaze #1 and Goryeo Green Glaze #2—which look to earlier art forms to draw inspiration from, as well as to question, artistic conventions.

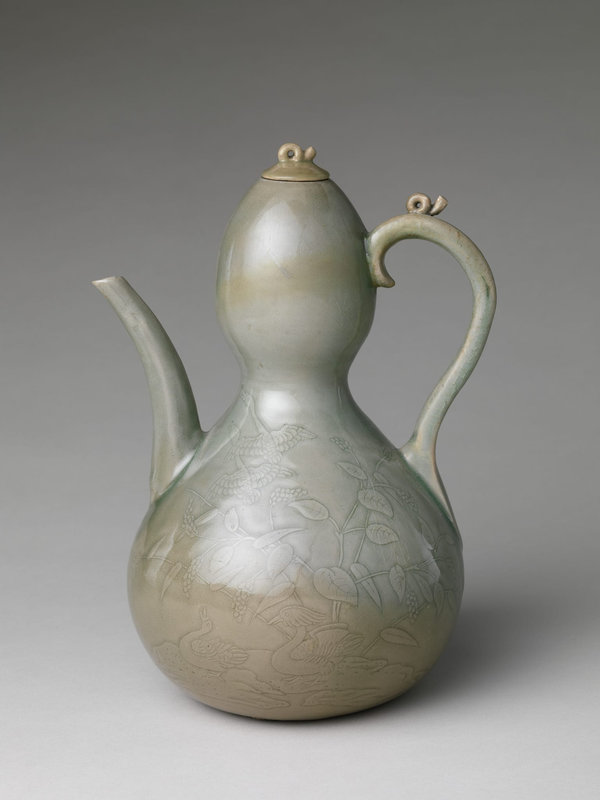

Gourd-shaped ewer decorated with waterfowl and reeds, Goryeo dynasty (918–1392), early 12th century. Stoneware with carved and incised design under celadon glaze. H. 26.7 cm; W. 20 cm. Fletcher Fund, 27.119.2. © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The decoration of ducks and geese amid reeds, expertly and sensitively rendered, demonstrates an appreciation for pictorial realism. Goryeo celadon features both naturalistic and more abstract designs. Examples such as this ceramic vessel provide a glimpse of what secular painting from the Goryeo dynasty mig niht have looked like, given that so few actual painted images survive.

Bowl with two boys and lotuses, Goryeo dynasty (918–1392), early 12th century. Stoneware with mold-impressed decoration under celadon glaze. H. 6.7 cm; Diam. 19.7 cm; Diam. of foot: 6.4 cm. Gift of Sadajiro Yamanaka, 1911 (11.8.6). © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ceramics with green glazes were the only high-fired wares produced in Korea during the Goryeo dynasty. The tradition of such high-fired green-glazed wares was first introduced from China around the tenth century. However, by the middle of the twelfth, Korean potters had developed distinctive traditions with shapes and designs that reflect native taste. These Korean wares were extolled in contemporaneous Chinese writings as having the radiance of jade and the clarity of water.

Vertical flute decorated with chrysanthemums, cranes, and clouds, Korea, Goryeo dynasty (918–1392), early 13th century. Stoneware with inlaid design under celadon glaze. L. 36.5 cm. Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2008.71. © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

An extremely rare celadon flute, this piece was probably custom-made and intended primarily as a decorative object rather than a functional instrument. The flying cranes, mushroom-shaped clouds, and miniature chrysanthemum blossoms inlaid along its body appear frequently on Goryeo celadon.

Tile decorated with birds and flowers, Goryeo dynasty (918–1392), 13th century. Stoneware with inlaid design under celadon glaze; 22.8 × 31.7 cm. Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2023 (2023.320). © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Celadon was the predominant ceramic produced during the Goryeo dynasty, made in a wide variety of forms, from bowls and ewers to decorative wall tiles. Tiles are among the thinnest types of celadon wares, and few survive intact. As a flat panel, tiles are also the ceramic form most like painting. Decorated with the sanggam inlay technique, this example features common motifs, such as cranes in clouds, wave patterns, and scrolling floral designs. However, the central scene within the ogival frame—two long-tailed birds in a tree, whose trunk and branches are wonderfully rendered through undulating lines—sets this tile apart from other surviving examples.

Byron Kim (American, born 1961), Goryeo Green Glaze #1, 1995–96. Oil on linen, 213.4 × 152.4 cm. Courtesy of Byron Kim. Image courtesy of Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul.

In the West, Goryeo (918–1392) celadon is synonymous with exceptional Korean art. Its most alluring feature is arguably its inconsistent, indescribable color. Is it gray-green? Green-blue? Green-bluish-gray? Recognizing that it is a fool’s errand to seek any one description, the Korean American artist Byron Kim created these paintings, part of a larger series, to explore celadon’s most sublime and transcendent characteristic. Kim equates a potter’s ornamentation and glazing process to that of a painter, stating “the belief in the beauty of Koryŏ [sic] green glaze reminded me of the value placed on abstract painting in Western culture.” His emphasis on color challenges convention without completely abandoning taxonomic structures. Employing seriality, the series opposes the oversimplification of objects and cultures, while also addressing artistic hierarchies and the sociocultural contexts that determine value.

Dish with inscription and decorated with chrysanthemums and rows of dots, Dish with inscription and decorated with chrysanthemums and rows of dots, mid-15th century. mid-15th century. H. 5.7 cm; Diam. 18.4 cm. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Colman, 1893 (93.1.216). © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The deep dish is ornamented with repeating stylized chrysanthemum flowers, alongside other designs. The object is typical of buncheong ware— characterized by white-slip decoration and produced on the peninsula from the late fourteenth through the midsixteenth century—with stamp-impressed designs.

Inscriptions indicate the court offices that commissioned the vessels. The dish was made in Gyeongju to be sent to the office of Jangheunggo, which supplied items like paper and mats to the court

Bottle decorated with flowering plant, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), late 15th–early 16th century. Buncheong ware with white slip and iron-brown. H. 25.4 cm. Purchase, Bequest of Mary Stillman Harkness, by exchange, and Friends of Korean Art Gifts, 2021 (2021.126). © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This flask-shaped bottle decorated with iron-brown flowering plant is an excellent and rare example of buncheong ware. Iron-brown ornamentation was primarily implemented in the Gongju Hakbong-ri kilns in South Chungcheong Province, of which the Met’s jar with floral scroll (2006.241) is a good example. Differing from that jar with the partially covered slip on a dark clay body, this bottle has a finer, white clay body that is almost entirely covered in slip. The flowering plant is represented in a whimsical manner with confident brushwork. These qualities indicate that this bottle was produced at the Goheung Undae-ri kilns in South Jeolla Province, a region that predominately produced incised and sgraffito buncheong wares (1986.305 and 16.122.1). There are only two other known examples of intact bottles with this design and they are in Japanese and Korean museum collections.

Jar decorated with dragons, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), 17th century. Porcelain with underglaze iron-brown design. H. 30.5 cm. Gift of Michael ByungJu Kim and Kyung Ah Park, 2022 (2022.437). © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This jar is decorated with two dragons pursuing a flaming jewel. The dragons are whimsically and dynamically rendered through energetic brushwork using iron-brown pigments rather than cobalt blue or copper red—colorants that were less readily available during the Joseon’s recovery after repelling invasions in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The jar’s buoyant, slightly asymmetrical silhouette is similar to that of so-called moon jars, undecorated white porcelain jars popular in the17th and 18th centuries.

Moon jar, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), second half 18th century. Porcelain. H. 38.7 cm; Diam. 33 cm; Diam. of rim 14 cm; Diam. of foot 12.4 cm. The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975 (1979.413.1). © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Moon jars have become national icons, inspiring the shape of the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympic cauldron and garnering record-breaking prices at auction. Thus it may be surprising that during the Joseon period these vessels were utilitarian objects, referred to as daeho (literally “big jar”), and fell out of vogue in the 1800s. Rediscovered in the twentieth century and called moon jars for their evocative forms, they are adored by many for unintentional features acquired during firing, such as asymmetry or the final hue. Because moon jars are made by joining two hemispheres, each example has a unique shape.

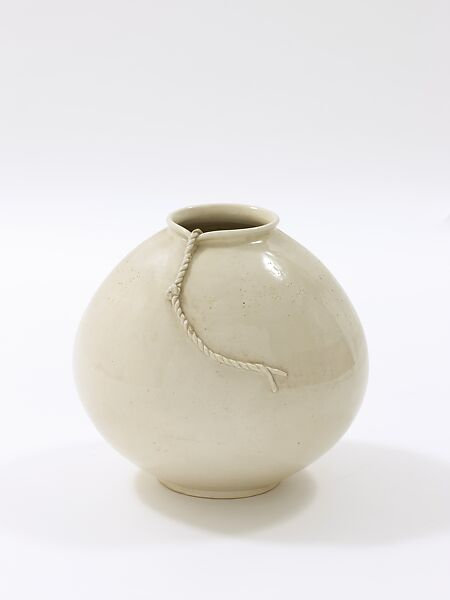

Lee Seung-taek (Korean, born 1932), Tied White Porcelain, 1979. Porcelain, 27.5 × 29 cm. Lent by a private collection.

Lee Seung-taek invokes earlier art traditions, like his teacher Kim Whanki, whose work is on view nearby, but Lee aims to challenge “stereotypical notions of materials” and to “transform the present into the past and the past into the present.” Adding a ceramic “rope” to a white jar transforms it from familiar to mysterious, enticing viewers to look inside for the source. By the twentieth century, porcelain jars were revered as elegant art objects embodying Confucian austerity. The rope confounds this reading, prioritizing the nonsensical over the elegant. In their postwar drive for reconstruction, the authoritarian Korean governments of the 1960s and 1970s placed a premium on value, whether functional or symbolic, and alignment with nationalist agendas. Through nonsense, Lee subverts these criteria. His work simultaneously revives traditional objects devalued in an industrialized society and challenges efforts to use those objects to craft essentializing nationalist narratives.

Dragon jar, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), second half 18th century. Porcelain with underglaze cobalt-blue design. H. 43.8 cm; Diam. 33 cm; Diam. of rim 15.9 cm; Diam. of foot 17.1 cm. Purchase, 2009 Benefit Fund, 2010 (2010.368). © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Porcelain jars painted with cobalt-blue dragons were popular from the seventeenth through the nineteenth century. Many were used as flower vases in official court ceremonies. Originally associated with water, dragons were also imperial emblems throughout East Asia. The two four-clawed dragons chasing flaming jewels on this piece embody the dynamic strength of the mythical beast. At the same time, dragons are seen as auspicious, welcoming creatures; the pair seen here, with their amusing faces, reflects the notion that they are not always to be feared.

Bowl with floral and abstract motifs and hangeul inscription, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), dated 1847. Porcelain with underglaze cobalt-blue design. H. 10.6 cm; Diam. 18.9 cm; Diam. of foot 8.6 cm. Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2010 (2010.174). © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The striking, abstract designs on this bowl closely resemble those found on so-called Kraak ware, Chinese export blue-and-white porcelain from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The style is unusual in Korean porcelain. Based on the Korean-character (Hangeul) inscription drilled over the glaze above the foot, we can surmise that this was one of thirty bowls for use at Sunhwa Palace on the occasion of the royal wedding in 1847 of King Heonjong (r. 1834–49) to his formally selected concubine.

Jar with floral roundels and inscriptions, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), 19th century. Porcelain with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration. H. 38.7 × Diam. 36.8 cm; Diam. of foot: 18.7 cm; Diam. of rim: 17.8 cm. Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2021 (2021.127). © 2000–2024 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Resembling a moon jar in shape and production method, this vessel is similarly formed by fusing two hemispheres. While its size and asymmetry exude the same unaffected charm that has made moon jars national icons, it is distinguished by its surface decoration. Cobalt-blue roundels with alternating floral and calligraphic motifs appear slightly above the central seam. The characters convey auspicious wishes for longevity (壽, su) and blessings (福, bok). The cobalt-blue reflects the popularity of blue-and-white porcelain in the nineteenth century. Purportedly collected by the Japanese potter Shimaoka Tatsuzo (1919–2007), jars like this played a part in the development of Japanese mingei aesthetics and philosophy, which celebrated everyday objects made by ordinary people.

The formation of lineages and histories cannot be separated from Places, the exhibition’s third theme. Place has long been deeply engrained in Korean art, notably in landscapes, with ties to notions of belonging, homeland, and identity. In the 20th century, with colonization and then the division of the peninsula, these notions about place take on additional implications of rupture, displacement, and separation, and these complexities can be seen in the works of Paik Nam-soon and Kim Hong Joo.

Kim Hong Joo (Korean, born 1945), Untitled, 1993. Oil on canvas, 145 × 112 cm. Courtesy of Kim Hong Joo. Image courtesy of Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul.

After decades of authoritarian rule in South Korea, the prodemocracy Minjung movement arose in the 1970s and culminated in the 1980s with the violent suppression of protests. Nevertheless, it paved the way for constitutional changes and South Korea’s first democratic elections, in 1987. Artists mirrored the political divide; realism was embraced by Minjung artists, while abstraction was seen as conservative. Kim Hong Joo’s art defies categorization and captures the uncertainty of the era. Here, the split composition might call to mind the partition of Korea by the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). In the upper half, the floating, silk-screened photographs of new and old buildings reflect societal upheaval from rapid modernization. In the lower half, the reservoir’s shape resembles the Korean peninsula but is also an upside-down anamorphic portrait of the artist, infusing the land with a human presence.

The last theme is People. Prior to the 20th century, calligraphy and landscape were the revered modes of painting, and figural representation was predominantly in the form of portraiture. From the muted but intransient women by Park Soo-keun, to the inscrutable male laborers by Lee Jong-gu, the expansion in the types of and manner in which people are depicted reflect the reconfiguration of the class system and the rapid comprehensive societal change that Korea experienced in the 20th century.

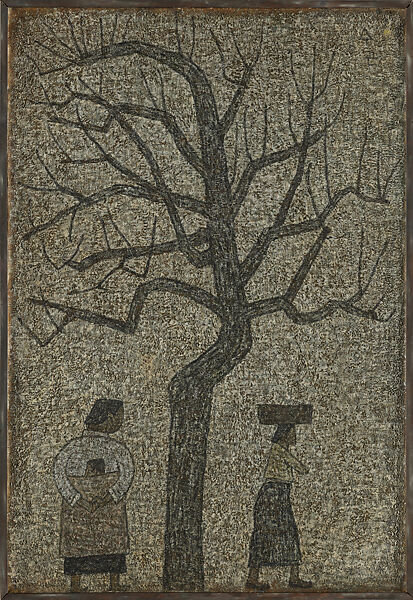

Park Soo-keun (Korean, 1914–1965), Tree and Two Women, 1962. Oil on canvas, 130 × 89 cm. Courtesy of Park Soo-keun. Image courtesy of Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul.

Having emerged from modest origins, Park Soo-keun aspired to be an artist after seeing a work by French painter Jean-François Millet (1814–1875). During the 1940s in Pyeongyang, inspired by granite Buddhist sculptures, pagodas, and unearthed Goguryeo (37 BCE–668 CE) tomb wall paintings, he cultivated his distinctive style of a muted palette and a textured surface often characterized as “stonelike.” Much of his work spotlights ordinary individuals, primarily women and children, echoing Millet’s influence. After the Korean War (1950–53), the loss of men resulted in widows, mothers, and daughters bearing the weight of reconstruction. Park’s depictions of toiling women, often alongside children, recognize their indispensability and empathize with their burdens. Painted in his rough style, the women take on a monumental permanence inspired by monuments and statues, a connection that may also be an artistic response to Korea’s rapid postwar transformation.

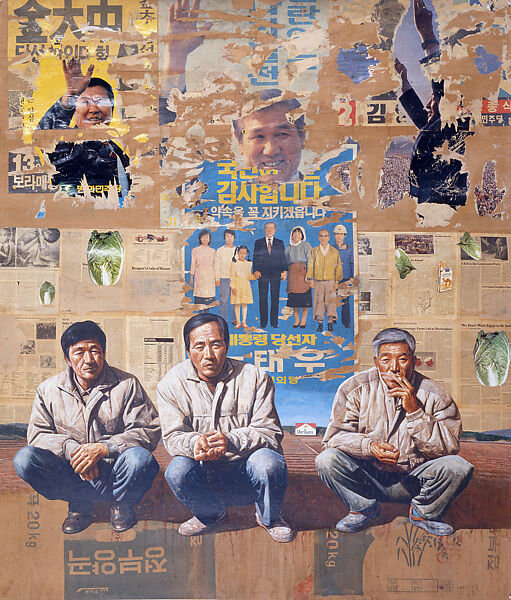

Lee Jong-gu (Korean, born 1954), Earth at Oziri (Oziri People), 1988. Acrylic and collage on a grain bag, 200 × 170 cm. Courtesy of the Artist and MMCA.

Amid increasing authoritarianism from the 1960s to the 1980s, South Korea underwent rapid industrialization and urbanization, sparking the Minjung grassroots democratization movement. In this context, artists such as Lee Jong-gu embraced realism as an intentionally politicized aesthetic language, challenging the subdued abstraction preferred by earlier figures, including Kim Whanki and Lee Ufan, and questioning the notion that “seeing is believing.” Lee Jong-gu’s hyperrealistic paintings vividly depict the harsh experiences of Korean farmers and laborers. This example is infused with skepticism, evident in the farmers’ expressions, torn posters showing right- and left-wing politicians with their campaign promises, and international political headlines. Lee often incorporated unconventional elements like cabbage and cigarettes, while repurposing grain bags as his canvas, highlighting the mundane. This approach challenged art norms, emphasizing that anyone and anything can be both subject and material for art.

Lineages: Korean Art at The Met is curated by Eleanor Soo-ah Hyun, Korea Foundation and Samsung Foundation of Culture Associate Curator of Korean Art.

Additional support for Korean Art at The Met has been provided by The Korea Foundation, the Samsung Foundation of Culture, and Michael B. Kim and Kyung Ah Park.

The establishment of and program for the Arts of Korea gallery have been made possible by The Korea Foundation and The Kun-Hee Lee Fund for Korean Art.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, a quarterly publication, has devoted the Summer 2023 issue to the exhibition.

The Bulletin is made possible by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Korea (MCST).

The Met’s quarterly Bulletin program is supported in part by the Lila Acheson Wallace Fund for The Metropolitan Museum of Art, established by the cofounder of Reader’s Digest.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F86%2F119589%2F111682578_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240504%2Fob_20ea9b_441245952-1663314104438602-70691540861.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240504%2Fob_515dba_441447797-1663308804439132-30041149197.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240508%2Fob_d997ec_d21e3e110569bdfa219529297300e28a-1402x.png)