'Boundless – A Maritime Perspective of East-West Cultural Exchange in the 16th Century' at National Palace Museum, Taipei

Onde a terra acaba e o mar começa.

“Where the land ends and the sea begins,” said the Portuguese poet, Luís Vaz de Camões (?-1580). These two lines described how the edge of the land was precisely the starting point of the sea. The context of his words bore witness to the desire for venturing overseas, which pervaded Europe during the 16th century, while encapsulating the encounters among people from different parts of the world.

It was a time when being attached to one place no longer sufficed, be it the land or the sea. Sailing afar time and again into uncharted waters, seafarers searched for opportunities and resources. It was a time when the first circumnavigation of Earth was completed, which gradually weaved through Asia, Europe, Africa and the Americas into a maritime perspective of the silhouette of the world. Unprecedented discoveries emerged near and far, germinating slowly and blossoming into ideas diverging from the past. It was a time of amazements and filled with profound changes, as French historian Fernand Braudel (1902-1985) called it, “the long 16th century.

This exhibition unfolds with a maritime beginning, where precious artworks from the National Palace Museum as well as major institutions both domestic and abroad converge to recount the stories of cultural encounters and fusion through voyages of the 16th century. Divided into three sections, the exhibition opens with The Maritime Era, in which objects such as nautical maps, silver coins and porcelains recovered from shipwrecks lay out a backdrop across the sea where Europe and Asia crossed paths and inspirations were roused. The Chance Encounter tracks the movement, interaction and rivalry among peoples from all corners of the world through literature, archives, goods and plant species. Taiwan, as a hub of convergence, also started making her presence on the world map at this time. Lastly, Emerging Intercultural Expression highlights items such as paintings, objects and maps as an exploration of the ample exchanges in art, knowledge and culture, while also delving into the new concept of being “global.”

The Maritime Era

The East Asian trade structure was anchored by the tribute/sea ban systems of the Ming court in China, though the smuggling trade was also thriving. The arrival of the Europeans accelerated the waning of the sea ban policy. As a response to the changing times, the Ming dynasty finally legalized international trade in Yuegang, Zhangzhou, Fujian province in the late1560s.

Goods, plants and silver circulated throughout the world in massive quantities for the first time in history, bringing people a newfound understanding of the sea. Aside from the resources and opportunities, challenges also presented themselves. The sea, as the bridge between the landmasses, preluded a new age for the flow and movement of goods.

Maris Pacifici (Description of the Pacific Ocean), 1589, Abraham Ortelius, Netherland. Height 56.9cm, Width 47.1cm. National Museum of Taiwan History, 2009.011.0460.

Copper-plate printed on paper and hand colored, Maris Pacifici (Description of the Pacific Ocean) is from the 1601 edition of Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Atlas of the World) by Netherlands cartographer Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598). It is the earliest known printed map to feature the Pacific Ocean. On the right is the Americas, and on the left are the East Asian Seas. Occupying the bottom portion is the hypothetical continent, Terra Australis (the Southern Land), also called Magellanica. The vast water body in the middle is the Pacific Ocean. A ship on the lower right is led by an angel across the Fretum Magellanicum (Strait of Magellan), entering the Pacific Ocean through the southern tip of South America. The ship is a depiction of the Victoria, one of Ferdinand Magellan’s (1480-1521) squadron of kraak during his circumnavigation around the globe.

Portugal and Spain had been locked in a tight race of maritime expeditions since the late 15th century. In 1519, King Carlos I (1500-1558) of Spain funded Portuguese explorer Magellan’s expedition, which set sail from Seville. The long and treacherous voyage ended in 1522 with the return of the only surviving ship, the Victoria. Magellan’s circumnavigation inspired the creation of Maris Pacifici as well as similar nautical maps that followed, reflecting Europeans’ fervent passion for maritime expedition in the 16th century.

Dongxi Yang Kao (On the Eastern and Western Oceans), 1617, Zhang Xie, Ming Dynasty. Qing manuscript copy of the Siku Quanshu (Wenyuange Edition), Qianlong reign. Length 31.5cm, Width 20cm. National Palace Museum, Gu Ku 012877-012880, National Treasure.

Completed in 1617, Dongxi Yang Kao (On the Eastern and Western Oceans) is an important document about the oceans from the Ming dynasty. The author, Zhang Xie, whose style name was Shaohe and sobriquet Haibin Yishi, was a native of Longxi, Fujian. Zhang compiled the individual Haidao Zhenjing (nautical routes and compass charts) from the Ming dynasty into one document and added contemporary events. Dongxi Yang Kao sums up the countries that had come into contact with southeast China up to the early 17th century as well as the trade activities.

Countries listed in this book are divided into a group of 15 from the west oceans and a group of seven from the east oceans. Japan and Dutch are singled out in Waiji Kao (Additional Records). Descriptions of each country begins with a historical background, followed by details on notable landmarks, local products and trade. Countries from the west oceans include Cochin, Champa, Siam, Xiagang (modern Java), Cambodia, Dani (modern Kelantan), Palembang, Malacca, Aceh, Pahang, Johor, Dingjiyi, Sigi Gang, Bandjarmasin and Chimen (Timor) with information regarding geography, history, climate, attractions and products, a truly thorough account.

Dragon-shaped Kendi in Underglaze Blue, Ming Dynasty, Wanli period, ca. 1575-1600. Height 22.4cm, Diameter (Rim) 5.7cm. Rijksmuseum AK-RAK-1981-1.

The term, “kendi,” is derived from Sanskrit, referring to “kundika,” a vessel of ritual liquid and a daily object in India. In China, most kendis were produced in Jingdezhen and the Dehua kilns, and some were produced in Swatow. The majority of kendis produced during the Ming and Qing dynasties were exported to Southeast Asia. With a dish-shaped rim, this kendi has a long and slender concaving neck, ovaloid belly and flat foot. A dragon ascending along the curved belly and looking upwards functions as the spout. The rim and the neck are embellished with four tiers of patterns. From the top down are a band of triangular decoration; twined floral motifs; cloud-shaped panels filled with Chinese chainmail motifs; banana-leaf lappet motifs. The left and right shoulders are adorned with the dragon’s spreading wings with its scales exposed on the back, and the belly is painted with the wave patterns. Scholars had pointed out that this kendi was paired with a lid, which has been lost.

This piece is dated to approximately the late 16th century, a period when Jingdezhen produced kendis in additional animal forms such as the elephant , toad and phoenix.The elephant- and toad-shaped kendis are also among the collection of the shrine of Shaykh Safi al-Din Ardabili in Ardabil, Iran. The pairing of the winged dragon motif with the wave motif in underglaze blue started in Jingdezhen back in the 15th century. Examples include Bowl with Sea Creature Motif in Underglaze Blue and Stem Cup with Sea Creature Motif in Underglaze Blue from the Xuande reign (1426-1435), Ming dynasty from the collection of the National Palace Museum. Kendis in the form of a winged dragon are also among the collection of Sir Percival David (1892-1964, currently the British Museum collection). An example is the late-16th century Swatow ware, a kendi in the shape of winged dragon in wucai polychrome decoration.

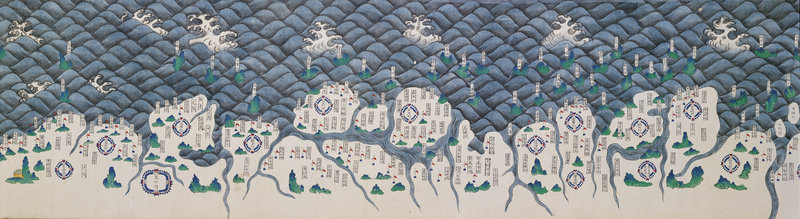

Nautical Map, ca. 1560s. Height 30.5cm, Width 2,081cm. National Palace Museum, Ping Tu 020865.

Color painted on paper, Nautical Map depicts coastal features such as the coastline, rivers and islands between Hainan Island and the Yalu River estuary in the style of a landscape painting. Land depictions focus on military strongholds such as military posts, citadels, waterfront fortresses and watchtowers, showing signs of influence from the 1562 Chouhai Tubian (Illustrated Book on Maritime Defense) by Zheng Ruoceng (1503-1570). At the frontispiece are four words, “hai bu yang bo” (a peaceful ocean without waves), and a brief account at the endpiece narrates the strategic defense along the coasts of Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangnan, Shandong, North Zhili and all of Liaodong. The section on Fujian mentions, “defense against intruders from Jinmen and Yuegang,” which dates this map to the 1560s, prior to the legalization of Yuegang as a trading port in 1567. Without a specific title, “Strategic Coastal Defense between Hainan Island and Yalu River Estuary” should be a fitting one based on the painting and the account.

Since the mid-14 th century, the Ming dynasty seized geopolitical and trade dominance in East Asia through the sea ban and tribute systems. However, smuggling remained an active form of illegal trading on the sea. Local forces formed alliances and weaponized, becoming what the government considered to be “pirates.” Nautical Map illustrates the coastal defense posts during the Ming dynasty with an emphasis on facilities like watchtowers, reflecting the coastal defense approach of Ming officials, such as Hu Zongxian (1512-1565) against piracy in the mid-16 th century. Drastically different than those from the European contemporaries, the map alludes to a weakening sea ban system.

Dish with Compass and Sail Ship Motifs in Wucai Polychrome Decoration, Ming Dynasty, Wanli Reign (1573-1620), Zhangzhou Ware. Height 7.8cm, Diameter (Rim) 34.7cm. Guimet National Museum of Asian Arts.

The Ming court lifted the sea ban during the reign of Emperor Longqing (1567-1572),and Yuegang, which is located in Zhangzhou, Fujian province, became a legalized port for maritime trade in China. Since then, the port had become a hub for merchants from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou to connect with the world. In addition to the Jingdezhen ware in underglaze blue, the ceramic ware onboard the ships bound for foreign destinations also included locally produced ceramics, which had been regarded as Swatow ware among the academia until the 1980s. The overturn came after archeologists discovered the kiln sites in Nansheng and Wuzhai in Zhangzhou, Fujian province. Through cross-comparisons made between the excavated and collected pieces, it is confirmed that a portion of the so-called Swatow ware are actually from the Zhangzhou kilns, including this unique large dish from the collection of the Guimet National Museum of Asian Arts in France. As shown in the photo, the upper surface of this dish is decorated with motifs in overglaze alum red and turquoise blue. Written in the center are three characters, “Tianxia Yi (One under the Heaven),” surrounded by two circles of inscriptions. The inner set refers to the nine stars in the Taoist Big Dipper, which consists of the two “attendant” stars, and the outer set refers to the heavenly and earthly ordinals as well as the divination hexagrams from YiChing (Book of Changes). Additional decorations include the sailing ship, fish, wave, mountain and constellation motifs. Works of similar style are also found in museums in countries such as Japan and the Netherlands. In particular, the excavated pieces from the Jokamachi (castle town) in Osaka, when paired with the collected pieces in Japan, may explain the export of Zhangzhou ware to not only the neighboring regions, but throughout Europe as East Asia aligned with the global trade after the second half of the 16 th century.

Also worth noting is that the inscriptions in the center of the dish, “Tianxia Yi,” may be interpreted as anchoring the world through one direction. Under the context of maritime exploration, perhaps dishes such as this, as scholars pointed out, could be used as a backup compass during the voyage.

The Chance Encounter

On the blue stage over the boundless sea and through expeditions from all corners of the world, the means for connecting and opportunities for chance meetings gradually materialized. From different departure points, people sailed into the known and unknown, and together, they have co-written legends and tales with deep resonance.

Since the second half of the 16th century, the tribute system and the sea ban policy of the Ming court had grown weak. While the monarchy continued its dominance, substantive changes already occurred among the people in the East Asian Seas. The merchant-pirates from Fujian and Zhejiang and the multi-ethnic “wokou,” pirates of Chinese and Japanese origins, emerged with powerful maritime force. Meanwhile, Europeans arrived in Asia by sailing around Africa to cross the Indian Ocean or crossing the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Their arrival sent a surge of diverse vitality into Asia. Quietly, export porcelains with exotic decoration and produce from the Americas changed what was everyday living around the world. Taiwan, right where we are, also started to shine on the stage at this moment in time.

Narcissi and Chimonanthus, Qiu Ying, Ming Dynasty, 16th Century. Hanging Scroll. Image Height 47.5cm, Width 25cm, National Palace Museum, Gu Hua 002191.

Qiu Ying (fl. 1494-1552), style name Shifu, sobriquet Shizhou, was a native of Taicang, Jiangsu province and a painter famed for his landscape, figure, animal, flower and ruled-line paintings. Ingeniously juxtaposed is a branch of chimonanthus extending gracefully above a pair of narcissi amid the frigid winter. While alluding to virtuous gentlemen, the flowers are also embedded with seasonal greetings. Depicted with precision, elegance and a refreshing air, the composition, outline and coloring techniques show influence of the Southern Song dynasty court paintings such as Ma Lin’s Layered Ice Silk, which deviates noticeably from the literati paintings. Qiu’s intricate style is exuberant yet classically elegant, exact yet refined, making him the most famed professional painter in Suzhou during the 16th century. The market was inundated with forgeries of his paintings, reflecting his popularity as well as the local taste in art.

Despite his popularity, there is no evidence suggesting that the Japanese emissaries were ever avid collectors of Qiu’s work, perhaps due to his being labeled as professional rather than literati in terms of identity and style. It was not until the beginning of the 17th century with the influx of forged paintings claiming to be the collaborative work of Qiu Ying and Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) that his position in art history finally shifted.

Stem Bowl in Underglaze Blue with Gold Floral Motif in Red Ground, Ming Dynasty, 16th Century. Height 10.2cm, Diameter (Rim) 13.1cm, Diameter (Foot) 4.1cm. National Palace Museum, Gu Ci 002810.

The interior and exterior of the stem bowl are adorned with two different glazes. As shown in the photo, the interior features a band of diamond-shaped motifs filled with crosses in underglaze blue underneath the rim. In the center of the stem bowl, a bird rests on stemmed branches enveloped by two concentric circles. The exterior is decorated with alum red ground with gold-foiled lotus motifs. The red sets off the lavish gold, like a golden brocade. Hence after the 19th century, this style gradually adopted the name “Kinrande (gold brocade)” from the Japanese scholars and achieved global recognition.

For this special exhibition, the National Palace Museum has displayed one of the only two such specimens to match their counterparts from the Topkapi Palace Museum in Turkey and explain how they were introduced to the Islamic court in the 16th century. As shown on one of the surviving Kinrande porcelain bowl, a silver base was mounted with inscriptions added, documenting the purchase of this porcelain in 1583 by the royal House of Manderscheid-Blankenheim in Germany. The owner later gifted the piece to an elder brother as a show of respect. Considering that the original owner once made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1582, and that the Middle East was a bridge between China and Europe in the 16th century, this type of porcelains could represent Chinese porcelains exported to Europe through the Middle East.

Meanwhile, Kinrande porcelains are also among the objects recovered from the Portuguese Espadarte (1558) and the Spanish San Felipe (1596) shipwrecks. The discovery can be compared against the Kinrande pieces found in Portugal and Spain to explain the global export of Kinrande as maritime routes expanded.

The “Magic Fountain” Ewer in Underglaze Blue, Ming Dynasty, Jiajing Reign (1522-1566). Height 31.2cm, Diameter (Belly) 16.7cm. Guimet National Museum of Asian Arts.

As illustrated, the ewer in underglaze blue is decorated with the fountain motif known as the “magic fountain.” Such ewers are rarely found and most of them lack reign marks. However, one of the ewers in the collection from Singapore is inscribed with Da Ming Jiajing Nian Zhi (Made in the Jiajing reign of the Ming dynasty), which scholars have used as evidence to date the “magic fountain” ewers to the 16th century. The author also considers the pear-shaped body and long hexagonal spout on the displayed ewer, which are shared by another ewer bearing the coat of arms of the Portuguese family of Peixoto as well as the mark of the Jiajing reign, to be viable sources of dating the “magic fountain” ewer.

Initially, scholars were intrigued by the foreign origin of the fountain motif. However, despite discussions spanning different generations, a consensus has not been reached to this date regarding whether the maker copied an actual image or relied solely on verbal descriptions to create the pattern. As shown on the vase, the three-layered structure towering over the basin is indubitably where the water valves reside. The water flows out of the animal mask decorations on the top and middle layers as well as both sides of the basin with a qilin crouching underneath. Such a unique design has inspired a multitude of research from diverse perspectives over the years that rendered three interesting explanations. The first attributes the origin of the “magic fountain” to the time of Ogedei Khan during the Yuan dynasty, during which foreign metalsmiths built the magic fountain in Karakorum, Mongolia. The second deems the 16th century Renaissance as the source of this motif. The third connects the motif to the international trade during the Age of Discovery, where the Western motifs introduced to China through missionaries. This allowed the Chinese ceramicist the opportunity to blend the Chinese traditional dragon and phoenix patterns with the new elements, resulting a unique style that reflected the fusion of the East and West.

Anping Jar, 17th Century. Height 16.6 cm/Height 14.5 cm/Height 11.3 cm. National Palace Museum, Zeng Ci 000531, 000532, 000534.

It is puzzling how a ceramic jar named after a city in Taiwan cemented itself in the history of Chinese ceramics. Anping Jar is a rare example, and a notable one. Named after Anping, Tainan, it is where considerable numbers of Anping Jars were excavated. Though categorized under a common term, they vary in size, glaze and thickness, likely the work of multiple kilns. The latest archaeological excavation and research indicate the production of Anping Jar in the Shaowu and Gaofutou kilns in Fujian province, China.

Excavation sites of Anping Jars are often accompanied by the 17th century settlements of the Spanish, Dutch and Zheng clan. The jars were used as containers for trading goods bound for Taiwan. The Anping Jars recovered from the General No. 1 shipwreck in the Penghu Sea and those from the collection of the National Museum of Taiwan History still have shells attached. They help provide a piece of the puzzle of goods being marine shipped to Taiwan. Though the jars are now empty, they might have carried liquor, gun powder and tea across the sea according to research. In particular, remnants of ropes around the opening of Anping Jars excavated from the Kiwulan site in Yilan indicate the need for sealing the jars.

Emerging Intercultural Expression

The Age of Discovery ushered in the age of exploration. Ardently or otherwise, countries joined in. From Taiwan, Japan and China in East Asia; from the Islamic world in West Asia; from Portugal, Spain and the Netherlands in Western Europe, exchanges of art and culture advanced considerably. Through diplomacy or war; through trade or prey; through movements temporary or permanent, such exchanges emerged as people converged, gradually morphing into a time unchained from the past; a time in which globalization was embraced.

Pendulating between the native and the foreign; weighing between business interests and self-actualization, artists and artisans reinvented foreign inspirations they seemingly understood. Through imitating, learning and interpreting; through perceptions and misperceptions, new knowledge encompassing both East and West was born; a diverse array of magnificent art was created. In forms tangible or intangible, the exchanges of art and culture reiterated, witnessing the intercultural expression emerging from human civilizations at this time.

Returning of Boat, Li Shida, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Fan Painting. Image Height 17.5cm, Width 52cm. National Palace Museum, Gu Hua 003556.

The folding fan is an important cultural symbol in East Asia. When they were first introduced to China from Japan through Goryeo Korea (modern North Korea) in the 10th and 11th centuries, they were rare goods owned by a small number of envoys and scholar-officials. In the 15th and 16th centuries, folding fans were imported to China in large numbers due to the expansion of the China-Japan trade. This prompted local imitations of folding fans and inspired Chinese artists to adapt this new medium for the creation of art. Fan paintings became popular in China and bore witness to interactions among the East Asian cultures.

Since the mid-16th century, Chinese painters of various backgrounds devoted themselves to the creation of fan paintings. As the featured fan paintings show, the curved fan shape and the portable nature of the folding fan affected artists’ approaches towards spatial composition and how paintings were viewed. It became a new means for expressing one’s identity, aspiration and sense of aesthetics, and became an item pursued by people of all social classes.

Li Shida’s (fl. 16th -17th centuries) Returning of Boat also replicates the trio of poetry, calligraphy and painting. However, his poem is intentionally colloquial and the focal point centers on the commotion over a spot on the ferry. The shift in expression is a sign of the wide popularity of folding fans, and of professional painters’ choice of daily subjects to the general consumer.

Lacquer Box with Chrysanthemum Décor, Japan, 17th-18th Centuries. Length 6.2cm, Width 9.5cm, Height 1.8cm. National Palace Museum, Gu Qi 000443.

Of the two fan-shaped lacquer boxes on display, one has a lid with realistic details of a folding fan. In addition to the clearly identifiable ribs, the surface is pleated and decorated with landscape and pavilions. The box contains two layers, each with a small piece of jade. On the second box, the fan-shaped lid is decorated with the rib structure that spreads into a flat surface adorned with the chrysanthemum and balloon flower motifs. The decoration was created using the taka maki-e (Japanese raised lacquering) technique, which results in a slightly raised effect. A piece of jade is also stored inside this box. Both boxes are containers of individual items inside the curio boxes created for the Qing imperial palace. The use of imported lacquer boxes for storing antiquarian collections reflects a sophisticated taste that echoes a curated attention to storage and appreciation, which was popularized by Treatise on Superfluous Things by Wen Zhengheng.

Next, the fan-shaped form is examined. Most of the similar pieces date back to the late 17th and mid-18th centuries. However, the large-scale export of maki-e lacquer ware from Japan to Europe and other parts of Asia after the end of the 16th century should be taken into account when rationalizing the context behind these two fan-shaped boxes. In other words, the introduction of maki-e lacquer ware from Japan to China could predate the late 17th and mid-18th centuries. As scholars pointed out, to explore when and how these two boxes were collected by the Qing court, one could reference to the objects presented to Emperor Kangxi in 1693 by Li Xu (1655-1729), who headed the Suzhou Weaving Bureau, and to the itemized list documented in the palace memorial, especially when the name, Li Xu, written in ink, appeared on the paper slips pasted under some maki-e lacquer ware from the Palace of Versailles and Guimet National Museum of Asian Arts in France. Among these pieces are fan-shaped boxes resembling the two from the National Palace Museum. A likely period of production and the context behind their origin could thus be established.

Furthermore, the cultural exchange that inspired the fan-shape design is explored. Academic research has all but confirmed that folding fans were introduced from Japan to China through Goryeo on the Korean Peninsula as early as the 10th to 11th century, and such spread was without interruption. In the 16th century, the literati in Suzhou expressed their longing for seclusion by painting scholars in the company of woods and springs on their fans. As the means of cultural exchange grew expansive and diverse, and with the introduction of Minggong Shanpu (The Fan Album by Celebrated Masters) from China to Japan no later than 1621, another wave of trends emerged. Consequently, fan paintings and fan-shaped objects gradually became fashionable motifs and designs.

Crescent-shaped Kendi in Underglaze Blue, Ming Dynasty, 16th Century. Length 20.5cm, Width 10cm, Height 15cm. National Palace Museum, Nan Gou Ci 000105.

This water vessel is shaped like the crescent of the new moon, which symbolizes new beginnings in the doctrine of Islam. During the Age of Discovery in the 16th century, a period marked by the establishment of new maritime routes, intercultural exchanges also introduced fresh elements to the objects in circulation. The decorative motifs identified on this vessel share similarities with those on the objects recovered from the Lena Shoal shipwreck. The similarities could serve as a reference for dating this vessel to between the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Additionally, observation of the 17th century metalware from the Metropolitan Museum of Art indicates that metalware is a likely inspiration for the crescent form of this vessel. Aside from objects in this form, the crescent moon was also used as a motif that paired with flowers, foliage and trees to create a moonlit scene, as depicted on the displayed pieces, be it the unmarked mid-15th century porcelains or the 16th century Jingdezhen ware marked with “Da Ming Jiajing Nian Zhi (Made in the Jiajing reign of the Ming dynasty).” The crescent moon motif is also identified on the specimens excavated from the ruins of Fustat, Egypt, which had been an interchange between China and West Asia since the 15th and 16th centuries. It appears that decorative patterns bespoke for the Islamic market had materialized from the porcelains that converged here.

Dish with Fish,Waterweed and Fishnet Motifs in Underglaze Blue and Overglaze Enamels, Ming dynasty, Tianqi reign (1621-1627), Jingdezhen Ware, Tenkei-akae. Height 3.7cm, Diameter 16.4cm. The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka 02334 Donation by Mr. HORIO Mikio.

Among the kosometsuke (old blue and white), which were mainly produced during the Tianqi reign in the Ming dynasty, those decorated with wucai (polychrome) enamels were called “Nankin akae” or “Tenkei akae” in Japan and enjoyed wide popularity. Scholars had long been perplexed about the exact kiln site in Jingdezhen where kosometsuke was produced until recent years. When specimens similar to the extant pieces collected in Japan were discovered at multiple locations in Jingdezhen, the production details of kosometsuke were finally revealed.

This dish is covered entirely with the fishnet motif in underglaze blue. A fish in the same cobalt underglaze adorns the center with three more in the surrounding decorated predominately in red glaze. Juxtaposed among the fish are three pieces of waterweeds in red and green glazes. The opposing stance between the “net” and the “fish” was cleverly captured by the artisan, leaving viewers wondering whether these fish are caught inside or have escaped out of the net. The bottom surface is also decorated with the fishnet motif. The ring foot is flat, caving inward and leaving the surrounding circle of biscuit exposed.

The decorative motifs on kosometsuke and Tenkei akae became the template for the 17th century Arita ware, the earliest porcelains produced in Japan, while leaving strong influence over the porcelains to come. The fishnet motif is still prevalent on tableware to this day as a part of daily life in Japan, indicating the popularity of kosometsuke and its integration into the Japanese culture.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_9bd94f_440340918-1658263111610368-58180761217.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_844371_440162278-1658267648276581-39734064969.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_78c699_440320998-1657454638357882-17494889713.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240421%2Fob_1dddd2_438878301-1654314112005268-81048289869.jpg)