'Inkstones, through the Eyes of an Aficionado' at National Palace Museum

"Inkstone aficionados" are individuals who are extremely infatuated with inkstones. Famous historical figures such as Su Shi and Mi Fu from the Song Dynasty, as well as Gao Fenghan from the Yangzhou School of Painting in the Qing Dynasty, were all renowned lovers of inkstones. What is it about inkstones that captivates people and makes them unable to let go? Let us appreciate the beauty of inkstones and share some intriguing stories about them.

Inkstones have accompanied people through the ages. In an era before computer keyboards were used and before fountain pens were invented, the use of brushes, ink, paper, and inkstones was required for writing and painting. Among these tools, inkstones have stood the test of time. For approximately 2,000 years, inkstones have undergone continuous changes, evolution, and refinement, much like the ebb and flow of fashion trends, exhibiting a multitude of forms and styles throughout different eras.

The exhibition will focus on the development and evolution of inkstone styles, interwoven with various aspects related to inkstones. We hope that everyone can experience the distinctive features of inkstones and immerse themselves in the emotions and sentiments of inkstone users throughout history, bridging the gap between the past and the present.

The Birth of Inkstone Styles

An inkstone, or "yan" in Chinese, is a tool used for grinding inksticks into ink. Hence, the basic functions and structure of an inkstone consist of a grinding surface called the "yan tang" and an ink reservoir called the "mo chi" or "inkwell." Inkstones are primarily made of stone or refined clay. Now that you have this information, you can imagine what an inkstone might look like.

Inkstone and People

Not only did scholars in the past have an inkstone on their desks, but it was also indispensable for painters, emperors conducting political affairs, and women writing poetry or teaching children. In cold weather, a warm inkstone was always accompanying people, and even during traveling, inkstones were essential items carried along in one's luggage. The inkstone of ancient times could be compared to today's mobile phones!

Warm inkstone with copper-alloy burner and spoon, Qianlong reign (1736-1795), Qing dynasty. © National Palace Museum.

Jade writing utensils box with inkstone, brush and spoon, 18th century, Qing dynasty. © National Palace Museum.

The Imagination of Inkstone Materials

Scholar Su Shi said that when he was twelve years old, while playing a game of digging in the vicinity of his residence, he once found a stone that was suitable for use as an inkstone. In this regard, the Inkstone material has great possibilities, considering the basic requirements of "easy ink dispersion." It would be even more ideal if the material also meets the criteria of beautiful stones. Have you ever considered using the wrist cushion for Chinese medical treatment or the roof tiles of a house as inkstones? And how can beautiful stones, such as jade or agate, transform into inkstones?

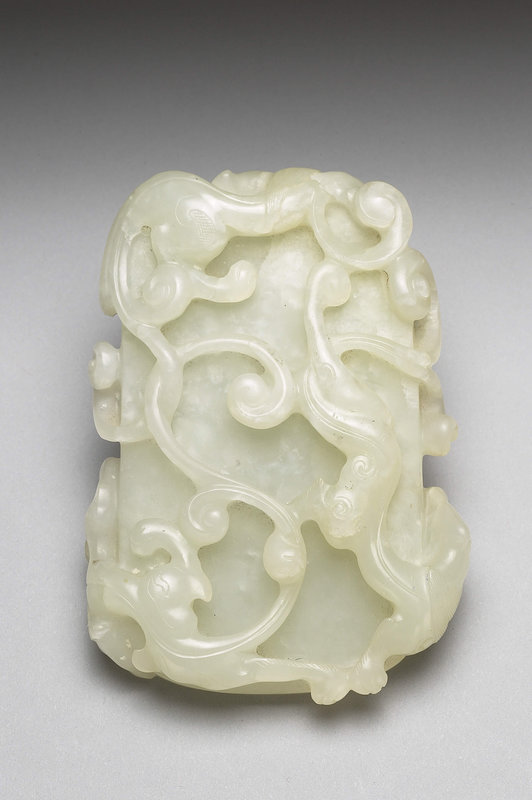

Jade inkstone with plum branch decoration, 17th century, Ming to Qing dynasty © National Palace Museum.

Porcelain pillow-shaped inkstone in yellow glaze, Tang dynasty (618-907) © National Palace Museum.

Early Inkstone Styles

The earliest artifacts that can be called "inkstones" in archaeological discoveries are the slab inkstones from the Warring States Period to the Han Dynasty. They were mostly made from natural stones, with a smooth and polished surface, and equipped with a grinding stone. During the Eastern Han Dynasty, three-legged inkstones made of stone materials with animal-shaped lids gained popularity. In tombs from the Six Dynasties, Sui Dynasty, and Tang Dynasty, multi-legged round inkstones were constantly unearthed, and they later became one of the traditional forms of inkstones imitated during the Song and Yuan Dynasties.

Tripod inkstone with decoration of a 'bi-xie (mythical creature)', Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) © National Palace Museum.

Porcelain tripod inkstone in celadon glaze, Western Jin dynasty (265-316). © National Palace Museum.

The Maturation of Inkstone Styles

With the maturity of the imperial examination system during the Song Dynasty, a large group of scholars emerged in society. This extensive population of literati laid the foundation for the development of inkstones in the future. Prior to 1987, students in primary and secondary schools in Taiwan used brushes to write compositions and often used rectangular inkstones to grind ink. This flat-bottomed inkstone style originated from the "chao-shou inkstone" of the Song Dynasty, which featured a hollowed-out base. Would you like to know how those inkstones evolved?

Inkstone in the Shape of the Chinese Character "Wind" (Feng)

The inkstone has feet at its base, and the tail of the inkstone is raised, making it convenient for the ink to flow backward towards the inkstone's head. There is no distinct separation between the inkwell and the inkstone platform. The tail of the inkstone is wide, while the head is narrow. When viewed from above, the inkstone's surface appears trapezoidal. The predecessor of this inkstone was the winnower-shaped inkstone.

Huocun inkstone in the shape of Chinese character 'feng (wind)', 11th-12th century, Liao-Jin dynasty. © National Palace Museum.

Inkstone in the shape of paired fish, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

Handle Inkstone

The handle inkstone was a popular style of inkstone during the Song Dynasty. It is characterized by a hollowed-out base, a steeply sloping ink reservoir, prominent edges, and a flat shape. Its predecessor was the Feng Zi inkstone (inkstone in the shape of Chinese character "feng"). During the Ming Dynasty, the handle inkstone had a smooth surface, and the base was often intentionally carved into a cylindrical shape to preserve the distinctive stone-eye feature.

Babana-white inkstone with wave pattern, Attributed to Song dynasty (960-1279) © National Palace Museum.

Handle inkstone with flame orb decoration, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

Rectangular Inkstone

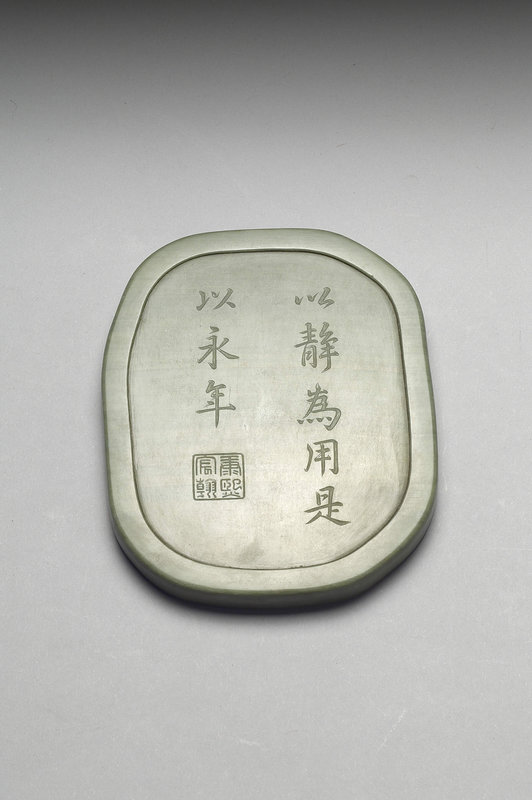

The rectangular inkstone is characterized by a base without feet or side walls. It features various forms of the ink surface, ink reservoir, and inkstone platform, such as the Phoenix pond (feng ci), enclosing pouch (gua nang), well-field inkstone (jing tian), and so forth. Each form carries different meanings and even blurs the distinction between the ink reservoir and the inkstone platform. This style showcases the natural texture of the inkstone itself and was one of the mainstream inkstone styles during the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Purple inkstone with phoenix-shaped pool, Song dynasty (960-1279). With inscription of Chunxi yuan-nian. © National Palace Museum.

She inkstone, Yongzheng reign (1723-1735), Qing dynasty. © National Palace Museum.

Unconventional Inkstones

Breaking free from the constraints of traditional inkstone shapes, unconventional inkstones draw inspiration from the natural form of inkstones or derive their designs from natural objects. This approach fills the inkstone with creativity and endless possibilities. In addition to their function in grinding ink, these inkstones emphasize their unique individuality, every one of which being a work of art.

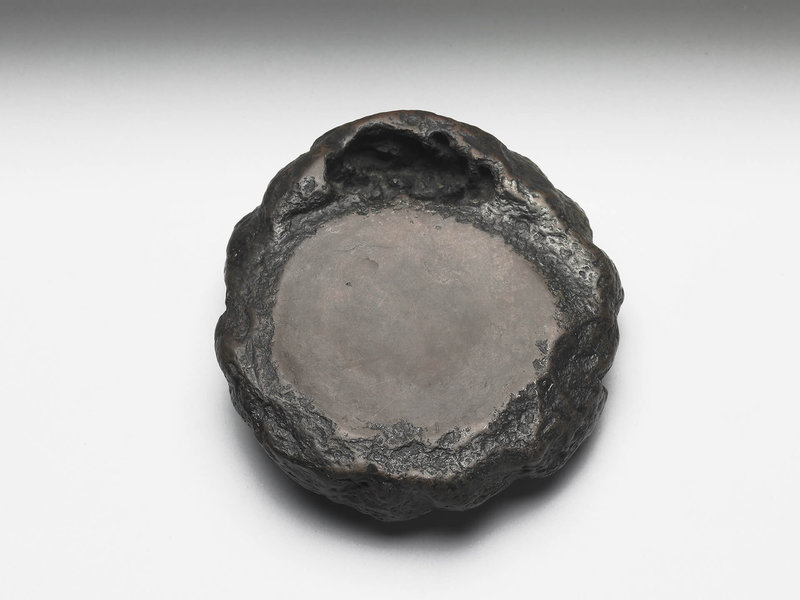

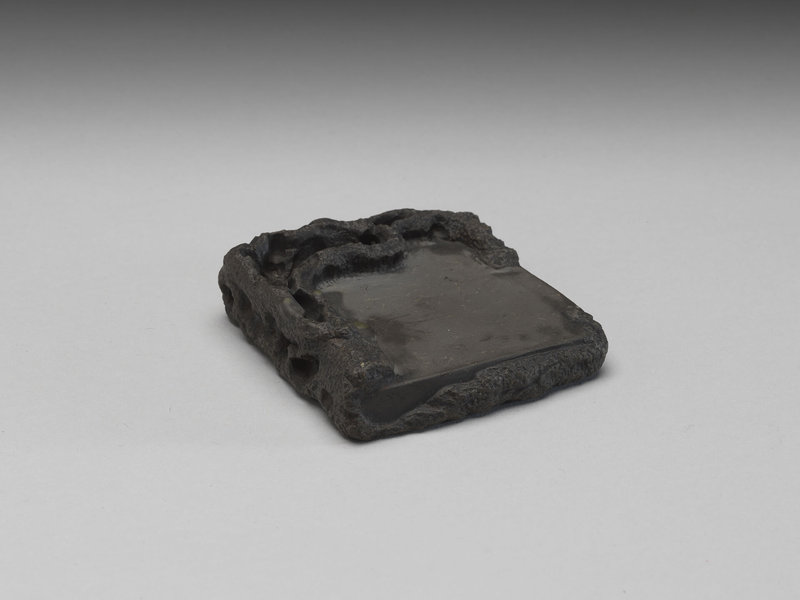

Inkstone with Natural Form

Usually referred to as "Zi Shi," which means the finest stone among larger stones, this type of inkstone is typically a naturally rounded stone. The stone surface is smooth and glossy, preserving the original shape of the stone with minimal modifications, resulting in an archaic and naturally beautiful appearance.

Duan inkstone made from naturally-shaped stone, Attributed to Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

Songhua inkstone with mother-and-pearl inlay, Kangxi reign (1662-1722), Qing dynasty. © National Palace Museum.

Sea and Sky Inkstone

Breaking free from the constraints of traditional inkstone shapes, unconventional inkstones draw inspiration from the natural form of inkstones or derive their designs from natural objects. This approach fills the inkstone with creativity and endless possibilities. In addition to their function in grinding ink, these inkstones emphasize their unique individuality, every one of which being a work of art.

Duan inkstone with imagery of heavenly seas. Attributed to Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

Duan inkstone with six dragons decoration, Ming dynasty (1368-1644) © National Palace Museum.

Figurative Inkstone

The figurative inkstone takes the form of tree trunks, leaves, gourds, bamboo, and other elements. The design considers both the surface and the back at the same time, creating a complete three-dimensional sculpture. The ink reservoir and other components of the inkstone are seamlessly integrated, showcasing intricate and ingenious details.

Bamboo-segment-shaped refined clay inkstone, Qing dynasty, 18th-19th century, Ji Nan collection. © National Palace Museum.

Refined clay inkstone in the shape of a banana leaf, Ming dynasty (1368-1644). © National Palace Museum.

Befriending the Inkstones

The inkstone was originally a vital tool for literati, and after establishing a strong bond with their inkstones, scholars would wash them, craft inkstone boxes, and care for them with love and attention. They would create rubbings and write inkstone catalogues to document their inkstones. Apart from this, scholars would gather with fellow inkstone enthusiasts to appreciate and talk about inkstones, forming a community of inkstone experts. What would you do for your cherished collections?

Cultural Memory

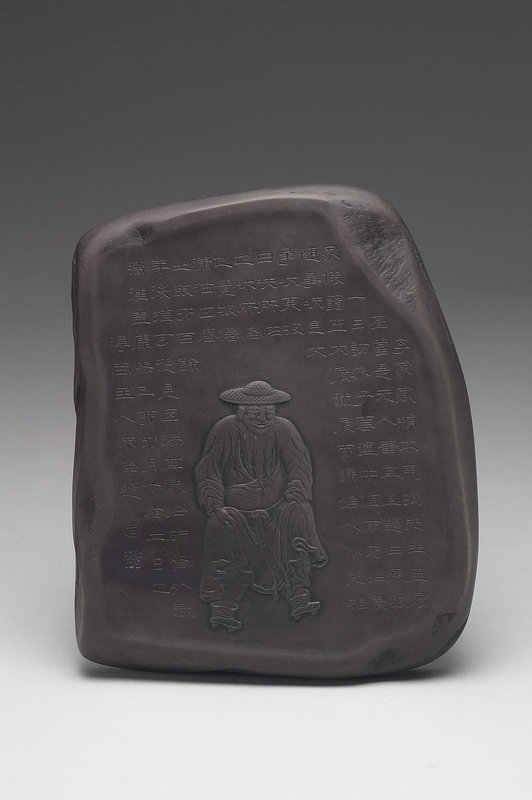

Inkstones, with their durable nature akin to stone tablets, can be passed down through generations and become carriers of cultural memory. The engraved inscriptions of cultural figures on inkstones evoke admiration and reflection on the past. Themes such as the Orchid Pavilion Gathering and the Writing Scriptures for Geese serve as inspirations while portraying the timeless literary legends of Su Shi.

Tao River inkstone with "Orchid Pavillion" motif, Song-Yuan dynasty (960-1368). © National Palace Museum.

Inkstone with figure of Su Dongpo, 17th- early 18th centuries, Qing dynasty. Inscription by Song Luo. © National Palace Museum.

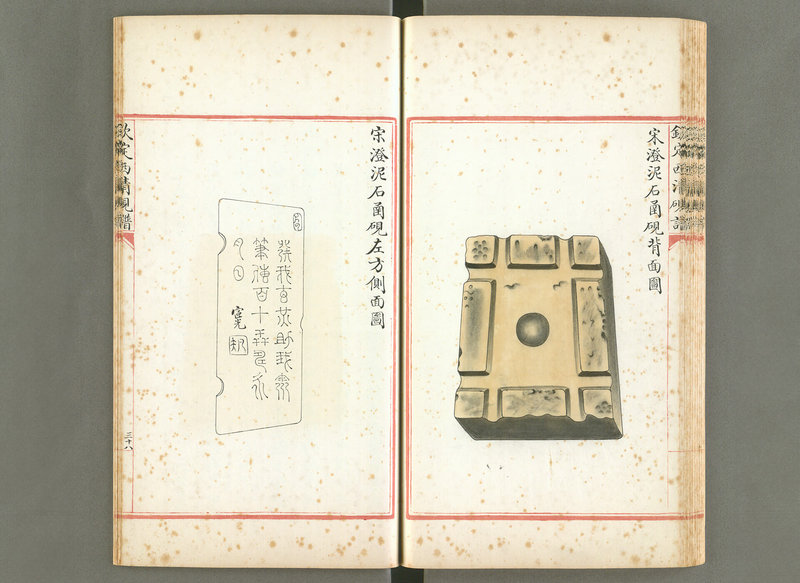

Preserving the Inkstone

An inkstone should never go unwashed for a day. Clearing the inkstone with clear water not only removes impurities but also nourishes the stone. To prevent the inkstone from drying out, it is advisable to store it in a dedicated inkstone box made of materials such as lacquer or wood rather than metal. These boxes are often custom-made to fit the inkstone precisely. Furthermore, for cherished inkstones that have been appreciated and examined, much have been passed down even without a camera. Drawing, making rubbings, and adding written descriptions can create enduring records, preserving their beauty and significance for an eternity.

Xipi lacquer box and wooden case with banana-white inkstone, 19th century, Qing dynasty. © National Palace Museum.

'Shih-han' refined clay inkstone, Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Inscription by Zhao Yikuang. © National Palace Museum.

Imperial Catalog of Ancient Inkstones, Qianlong reign (1736-1795), Qing dynasty. Compiled by Yu Minzhong et al., Qing dynasty, Qing court illustrated manuscript in red-lined columns. © National Palace Museum.

Inkstone Enthusiast Community

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, literati would form social gatherings to discuss poetry, politics, and engage in calligraphy and painting exchanges. Those who had a fondness for inkstones would appreciate and collect them, inscribe words or dedications on the inkstone, and exchange these inkstones as gifts. Scholars skilled in carving inkstones would collaborate with artisans well-versed in literature, intertwining the inkstone with their scholarly careers, social connections, and life experiences. Even as times changed, the inkstone remained, bearing witness to the people and events of the past.

Inkstone with paired swallow decoration, 18th century, Qing dynasty. Crafted by Gu Erniang. © National Palace Museum.

"Chun-shui-yu" inkstone, 18th century, Qing dynasty. Inscription by Lin Fuyun. © National Palace Museum.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240406%2Fob_de099f_435265592-1644340289669317-27147449708.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240310%2Fob_c0e13b_431753965-1629270041176342-17091014609.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240229%2Fob_7c7d11_428701194-1625292201574126-44092414790.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240229%2Fob_b5ac39_428703110-1625267244909955-59751988979.jpg)