“Anatomy of a Masterpiece” au Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

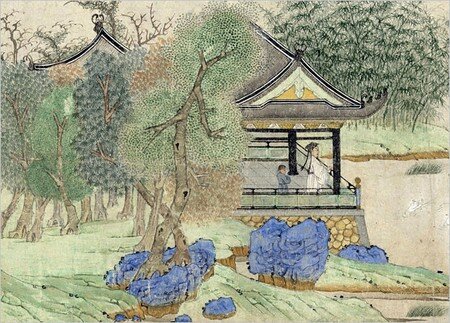

From his terrace, the world is blue and green — mountains and trees — or almost green. Spring is on the way; the geese are back. One, then two, alight on the river, with more still invisible but close behind. Pavilion living! The only way. With the city somewhere down there, and nature everywhere up here, he watches mist rise. River meets sky.

“Wang Xizhi Watching Geese” by Qian Xuan (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The calm watcher is the fourth-century scholar-artist Wang Xizhi, father of classical calligraphy and model for living an active life in retreat. He is depicted by the painter Qian Xuan, another connoisseur of reclusion, in a 13th-century handscroll at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The scroll is in “Anatomy of a Masterpiece: How to Read Chinese Paintings,” a spare, studious show that offers, along with many stimulations, a retreat from worldly tumult — the religious fervor, the courtly pomp, the expressive self-promotion — that fills much of the museum.

Detail of “Wang Xizhi Watching Geese” by Qian Xuan (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

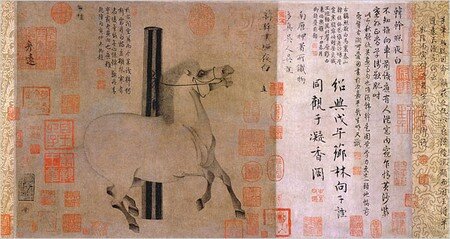

Han was a master of this, bringing an animal to life with contour lines and calligraphic strokes that look almost joltingly vibrant. And if that dynamism escapes us, the testimony of generations of connoisseurs is there to confirm it: the horse is hedged in by a halo of seals applied by scholars and artists over the centuries. Each is a stamp of approval; together they are a storm of applause.

The exhibition opens with “Night-Shining White,” a picture of a spirited horse by Han Gan, who lived in the ninth century during the Tang dynasty. By that point the criteria for a successful painting had been established, and the first was the ability to convey a subject’s vitality, or life-energy. (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

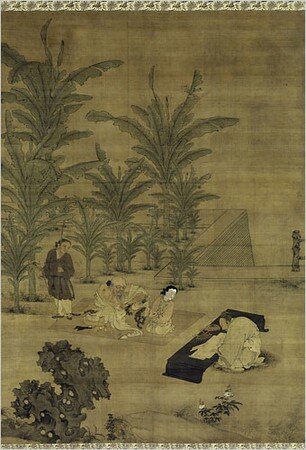

During the Tang dynasty, figure painting was the prestige genre, and landscape subsidiary. With time this hierarchy was reversed. Landscape became the big picture, figures mere dots to establish scale. And the scale was tremendous: towering mountains, limitless vistas, sourceless rivers, as befitted an image of nature that was an emblem of creation itself, a vision of matter forever consolidating and evaporating.

“Fu Sheng Transmitting the Book of Documents” by Du Jin (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

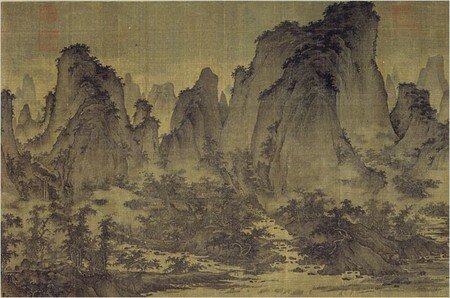

The uses of that vision varied. In “Summer Mountains,” attributed to the Southern Song painter Qu Ding, the landscape is descriptive, a pileup of painstakingly rendered details, from minute curved bridges to an elaborate temple tucked in a notch. By contrast, in Guo Xi’s water-soaked “Old Trees, Level Distance,” emotion reigns. The landscape looks as shadowed with regret as a Mahler song. Two old men, tiny figures, meet for a parting meal before one begins a journey. Where is he going? Will he return? Or is this a last goodbye? The men are dwarfed by a landscape seen through tears.

A detail from ''Summer Mountains,'' attributed to Qu Ding (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

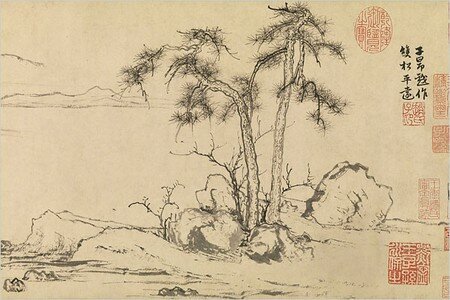

Several generations later, in Zhao Mengfu’s “Twin Pines, Level Distance,” something new appears. No more realism; no more romanticism; in a sense, no more painting. Now the landscape image is an extension of writing, a form of embodied thought, an essence of landscapeness, a text to be read. In the contemporary West we have a term for this: conceptual art. (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Anatomy of a Masterpiece” runs through Aug. 10 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, (212) 535-7710, metmuseum.org.

Lire l'article "The Art Is in the Detail" de Holland Cutter http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/14/arts/design/14asia.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240518%2Fob_60d595_444216558-10227922422179103-2007077639.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240515%2Fob_4a80af_2.png)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240515%2Fob_a65d19_1-1.png)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240515%2Fob_d1ec88_telechargement-11.jpg)