“Art of the Royal Court: Treasures in Pietre Dure From the Palaces of Europe” @ the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

A portable altar from the 17th century. Photo: Ruby Washington/The New York Times

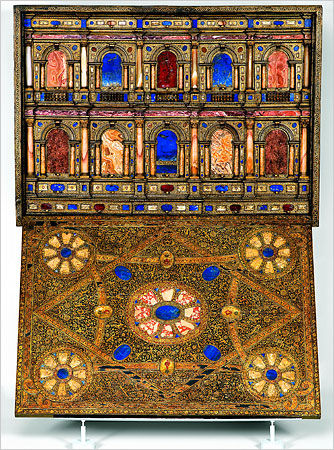

Roberta Smith writes: “Art of the Royal Court: Treasures of Pietre Dure from the Palaces of Europe” is a stealth blockbuster at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A sumptuous sprawl of 170 objects borrowed from palaces and museums all over Europe, it is the first in-depth survey of the arts and crafts of pietre dure. That Italian term, which translates as hard rock or hardstone, refers foremost to an intricate inlay of finely cut, highly polished slices of semiprecious stones: agate, lapis lazuli, jasper, carnelian, alabaster, rock crystal, amethyst.

A collector's cabinet from Venice (1565-80) Photo: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Kunstgewerbemuseum

Pietre dure could be flat. Fashioned into radiantly colored geometric patterns, floral designs, landscapes or mythological scenes, it was incorporated into tabletops, cabinets of all sizes, wall panels, portable altars, jewelry boxes and other furnishings. Such works could also be in the round.

A cabinet made for Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, also known as Pope Urban VIII (circa 1606-23). Photo: Ruby Washington/The New York Times

The show traces pietre dure’s emergence in Italy in the late 16th century and then follows its spread, often with Italian master craftsmen lured northward, throughout Europe and Russia and into the early years of the 19th century.

Since great pietra dure never lost value or went out of fashion among aristocrats or their cabinetmakers, the French and English recycled it into the designs of later periods.

But stone had been treasured and constantly reused for millenniums, as suggested by the show’s small opening gallery devoted to “origins.” The displays reach back to ancient Egypt, in the form of a lion-size sphinx, and ancient Rome, in a tiny perfume bottle in swirling agate, shown at left, and to 12th-century Italy, as a hefty jug in rock crystal from a Norman workshop attests. Photo: The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

The 16th-century Romans used stone tiles from the Baths of Caracalla for their monumental tables. A large vase and pedestal from Versailles, both in a brown-flecked stone with gilded bronze mounts, were cut from a single column of Egyptian porphyry that probably came from a building in ancient Rome. Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art

The show cuts a broad and flamboyant, if sometimes bewildering, swath through the history of art, objects and taste; the courses of empires; and the extremes of princely whims. One Humvee-size cabinet was commissioned by Cosimo III de’ Medici. A symphony of pietre dure flowers, it centers on a statue of his son-in-law, wigged and wearing footless tights carved in amethyst. Photo: Ruby Washington/The New York Times

At the show’s heart is the constantly shifting use of stone, especially the flat pietre dure. An example of this includes the fabulously accurate undergrowth of grape vines, butterflies and birds on a table with Eucharistic symbols. Photo: Palazzo Pitti, Florence

“Landscape with the Sacrifice of Isaac” from the Castrucci Workshop in Prague. Photo: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

In a panel depicting Abraham and Isaac, description and spatial logic are disrupted by the wonderful textures of the stone, which turn the image into a kind of puzzle. This effect is fine-tuned with striking contrasts of colors and textures that imbue small Breughel-like scenes with an explosive energy bordering on animation.

The dialogue between pietra dure and painting intensifies, as trompe l’oeil comes into fashion. On several occasions in the exhibition, pietra dure “paintings” hang beside the actual paintings on which they were based. Their stay-fast colors and paint-by-numbers crispness tend to carry the day, especially in a view of the Pantheon from the 1790s. Photo: Museo dell'Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence

A reliquary casket from the 15th century. Photo: Museo dell'Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence

“Pietra Dure” has something for every taste, meaning that almost all of us will find something in it that seems disconcerting or ugly in its excess. But over all, this extraordinary show suggests why the quest for beauty may be hardwired into humans. Nature habituated us to beauty, and we feel driven to equal its high, inspiring standards. (source www.nytimes.com)

“Art of the Royal Court: Treasures in Pietre Dure From the Palaces of Europe” continues through Sept. 21 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, (212) 535-7710, metmuseum.org.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_c453b7_439605604-1657274835042529-47869416345.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_59c6f0_440358655-1657722021664477-71089985267.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_07a28e_440353390-1657720444997968-29046181244.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_0b83fb_440387817-1657715464998466-20094023921.jpg)