Juanqinzhai : Long Forgotten in the Forbidden City

For decades stories circulated among art historians of a mothballed Qing Dynasty retreat within the Forbidden City, the imperial behemoth with 8,700 rooms that anchors the Chinese capital. Word eventually reached the World Monuments Fund, a nonprofit organization dedicated to saving imperiled historic sites. Six years and $3 million later the first building of the Palace of Tranquillity and Longevity to be restored, Juanqinzhai, left, has just been completed and will open to the public in the coming months.

A compulsive poet who oversaw the unprecedented expansion of China’s borders, Emperor Qianlong began creating the refuge in 1771, at 61, for his golden years. Employing the finest craftsmen of the day he spent five years building a fanciful collection of pocket gardens, banquet rooms, prayer halls and a single-seat opera house.

The wall of a theater inside the pavilion.

However, he died, at 89, without ever having spent a night in the palace. Emperors came and went, but somehow Qianlong’s two-acre jewel box remained untouched. In 1924, the gates to Qianlong’s miniature palace were chained shut and largely forgotten.

A silk panel on a wall inside Juanqinzhai.

In a country where historic preservation usually entails razing a structure and replacing it with a brightly painted replica, Juanqinzhai is something of a milestone. The pavilion’s slavishly faithful restoration is an archetype that both Chinese and American conservators hope to replicate over the next eight years, as the remaining 26 buildings in the complex are refurbished.

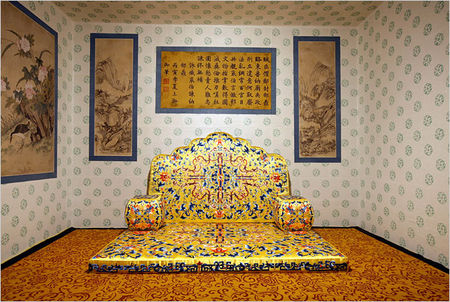

Juanqinzhai brings to life a level of detail rarely seen in historic Chinese buildings. Conceived as a pleasure pavilion, it is a simple rectangular box dolled up inside with translucent embroidered screens, jade-inlaid wall hangings and a distinctively Chinese form of carved decoration that involves layering bamboo skin atop dark zitan wood, left.

The pavilion is strewn with upholstered thrones — anywhere an emperor sat was a throne — and cloisonné tablets bearing Qianlong-inspired couplets.

The pavilion’s tour de force is the private theater, left, which provided the emperor with a cozy perch to view chaqu, a form of opera invented by a commoner that became all the rage in 18th-century Beijing.

Derided in the past for his family’s “barbarian” origins, Qianlong has been enjoying something of a renaissance in the past two decades, and a spate of recent architectural restorations in Beijing have embraced the “Qianlong style.”

Outside Juanqinzhai, a street in the Forbidden City.

Geremie R. Barmé, professor of Asian history at the Australian National University, said many historic buildings, including Juanqinzhai, were associated with more than one emperor and that preservation efforts should reveal that truth. “I think the results are lovely,” he said, “but after a while it gets tiresome to see everything restored back to this presumed last great moment in Chinese history.”

Photo: Doug Kanter for The New York Times www.nytimes.com

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F51%2F84%2F119589%2F122518624_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F42%2F87%2F119589%2F112989160_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F52%2F119589%2F112495720_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F12%2F27%2F119589%2F96148405_o.jpg)