Mughal gem-set gold and jade objects and jewelry, India, 17th,18th & 19th century

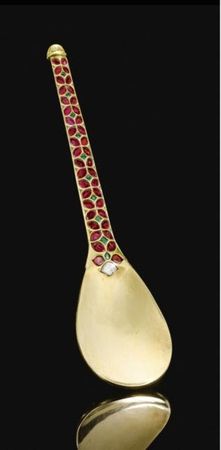

A rare Mughal gem-set gold spoon, India, 17th-18th century. Photo Sotheby's

the shallow bowl delicately inlaid on the reverse with a lotus rosette comprised of radiating foil-backed diamond petals and rubies, the faceted tapering shaft inlaid with emeralds and bands of ruby quatrefoils within an engraved and chiselled gold framework, gold lotus bud terminal; 14.5cm. Estimate 80,000—120,000 GBP. Lot Sold 409,250 GBP

NOTE: This spoon is comparable to the magnificent early-seventeenth-century spoon in the Victoria and Albert Museum (VAM 173-1910). The form of the V&A spoon, like our example, is derived from a European prototype and both are decorated, except for the inside of the bowl, with an interlace of rubies, emeralds and diamonds. The exact function of these spoons is unknown but Annemarie Schimmel has suggested that they might have been used to distribute sweets over which the Fatiha had been recited (Welch 1985, p.200, no.128).

During the seventeenth century precious objects were often set with gemstones in the manner seen here, as recorded by the traveller Jean de Thevenot who describes gold and gem inlaying at Agra (see India in the Seventeenth Century, Vol II, 'The Voyages of Thevenot and Careri', ed. J.P. Guha, New Delhi 1979) .The kundan technique employed for the settings is unique to India. Using hyper-purified gold (kundan), the inlayer (zar-nishan) refines the soft metal into strips of malleable foil which at room temperature have a 'tacky' or adhesive quality. Once cut and folded, the craftsman can apply the ductile gold as he chooses without any need for solder or glue. In spite of the practical advantages of this technique, it was only ever used in the Subcontinent, though widely imitated elsewhere (Keene 2001, pp.18 and 30).

The distinctive radiating lotus design on the back of the spoon relates closely to an architectural decorative device favoured during the reign of the emperor Shah Jahan. Interlocking panels radiating from a central rosette can be seen on the painted plaster ceiling of the Badshahi mosque in Lahore (1674 AD). A pair of late-seventeenth-century marble lotus-form stepping-stones from the collection of Howard Hodgkin (illustrated in R. Skelton (ed.), The Indian Heritage, London, 1982, no.12), display the same radiating petal design. The radiating lotus is an ancient symbol whose origins lie in the lotus roundels of early Buddhist monuments, such as the mahastupa at Amaravati, 2nd century AD.

A Mughal jade fly-whisk from the collection of the Viceroy Curzon, Northern India, 17th/-18th century. Photo Sotheby's

the stem carved in stone of mid-green tone of cup-form worked around the exterior with a frieze of upright stylized lotus leaves outlined with inlaid gold, the narrowed base swelling to a bulbous ridge inlaid with gold and rubies in a design of a foliate garland, the handle composed in sections of contrasting dark and pale green stone shortening toward a bud-form terminal; 19.8cm. Estimate 30,000—50,000 GBP. Lot Sold 49,250 GBP

PROVENANCE: George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, Viceroy of India (1898-1905)

Lady Alexandra Metcalfe (known to her friends as `Baba`) whose husband Edward Dudley Metcalfe (known to his friends as `Fruity`) stood as best-man at the Duke of Windsor's wedding in 1937

And thence by descent

NOTE: By the time of the Mughal Empire, the fly-whisk, or chauri, had left behind its functional role and had been established as an emblem of office, held above the head of a ruler at court and in royal portraiture. The role of holding the fly-whisk, the chauri bearer, had become an official court position. On coming to India, the British, both in the time of the East India Company and, subsequently, the British Empire, were frequently taken by these emblems of Mughal courtly life, affecting, to greater or lesser degrees, elements of these practices into their own daily lives. By the time Curzon came to India, the interest in such pieces tended to be more scholarly and even ethnographic though it is tempting to imagine that a viceroy might have thought it apt to possess such objects as the successors to Mughal rule. A century earlier, Clive of India, in effect, one of Curzon's predecessors, had owned three fly-whisks, all in banded agate (Powis 1987, pp.122-3, no.178).

Curzon was energetically influential in the British attempts to preserve Mughal monuments, playing a significant role in the conservation programme of several of them, notably the Taj Mahal and Humayun's tomb in Delhi. Amongst the other Mughal objects he collected was another fly-whisk that was subsequently given to the Victoria and Albert Museum (inv.no.255-1927). Both this and the present example would originally have been mounted with a yak's tail.

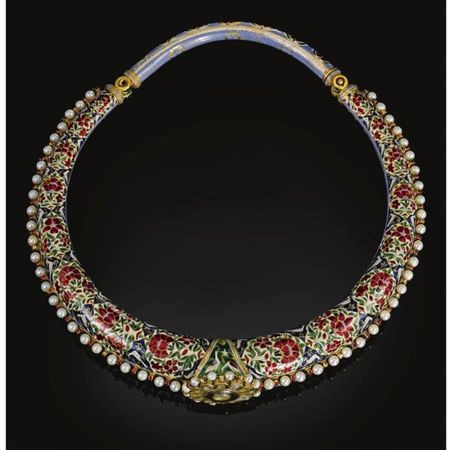

An enamelled and gem-set torque (hasli), India, Jaipur, 19th century. Photo Sotheby's

of rigid ovoid from, with an applied diamond-set rosette to the centre and bridge and pin clasp, the upper side decorated with diamond flowerheads and leaves reserved against a blue enamelled ground, the reverse decorated in red, green, white and blue enamels with cartouches of alternating flowerheads flanked by birds, the edges bordered with pale blue enamelling and pearls; 18.2cm. max. diam. Estimate 20,000—30,000 GBP. Lot Sold 25,000 GBP

NOTE: Mughal craftsmen inspired goldsmiths outside the confines of the court to produce jewellery that combined the ornamentation and refinement of the Mughal court with traditional rural forms such as the torque. This type of necklace might have been worn by the wife of a zamindar (landowner) or merchant. For a comparable hasli please see Markevitch 1987, p.44, no.15 and Untracht 1997, p.352, nos.776 & 777.

A Mughal Gem-Set Jade Crutch Hilt, India, 18th century. Photo Sotheby's

the pale green jade crutch hilt of bi-furcated form, the down-turned quillons with carved flower and leaf motif, both sides of the main body of the hilt with gem-set floral centre; 12.2cm. Estimate 8,000—10,000 GBP. Lot Sold 15,000 GBP

An Indian Gem-Set Gilt-Metal Casket with bird-head finial, India, 19th Century. Photo Sotheby's

of domed cylindrical form, wholly set with cut rubies, emeralds and diamonds, the four short feet designed as animal paws, the finial in the form of a parrot or falcon head, the cover fitted to the base with twist-lock opening smoothly to reveal plain interior; 7.5cm. height 5cm. diam. Estimate 10,000—15,000 GBP. Lot Sold 12,500 GBP

A gem-set jade archer's ring, India, circa 1800. Photo Sotheby's

the pale grey jade of typical form inlaid with foliate gold tendrils issuing kundan-set buds and flowerheads of emerald and ruby encircling a central cut-diamond; 4.5cm. Estimate 4,000—6,000 GBP. Lot Sold 5,000 GBP

Sotheby's. Arts of The Islamic World, 06 Apr 11, London www.sothebys.com

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F06%2F39%2F119589%2F129007933_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F83%2F41%2F119589%2F128989180_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F65%2F49%2F119589%2F128551133_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F78%2F119589%2F126903004_o.jpg)