New York – On March 15, Christie’s will offer Important Chinese Art from the Fujita Museum, a selection of 31 Chinese works of art, including highly important Shang and Zhou dynasty ritual bronzes, classical paintings, Buddhist stone sculptures, celadons and scholar’s objects. All of the works were collected by Denzaburō Fujita (1841–1912) and his two sons, Heitarō Fujita and Tokujirō Fujita, who were amongst the premier collectors of Asian art the Kansai region of Japan. Until World War II, the Fujita family acquired Chinese art exclusively through leading dealers Yamanaka & Company, for Chinese works of art, and Tanimatsuya (Toda Gallery), for Japanese art and tea wares. All of the Chinese objects in the sale were in the Fujita Collection prior to 1940.

Fujita Denzaburō

The Fujita Museum

Located in Osaka, the Fujita Museum ranks among Japan’s most eminent cultural institutions. The museum was founded in 1954 to exhibit works collected by the entrepreneur Denzaburō Fujita (1841–1912) and his sons, Fujita Heitarō and Fujita Tokujirō. The Fujita Museum collection comprises over 2,000 Japanese and Chinese works of art, including exceptional painting and calligraphy, Buddhist art, early bronzes, lacquerwares, textiles and tea utensils. The Museum’s prominence is exemplified by its nine National Treasures and fifty-two Important Cultural Properties, the most of any private museum in Japan.

Exterior of the Fujita Museum, Osaka

Archaic Bronzes

The auction includes four early Chinese bronze masterpieces — three extremely rare massive vessels and an extraordinarily rare ram-form gong. Each of these vessels date to the late Shang dynasty, 13th-11th century BC, and was intended to function as a container for wine. Serving in conjunction with a range of other vessel forms intended to contain either wine or foods, such vessels were used by the nobility in ritual ceremonies in which offerings of food and wine were presented to the ancestors.

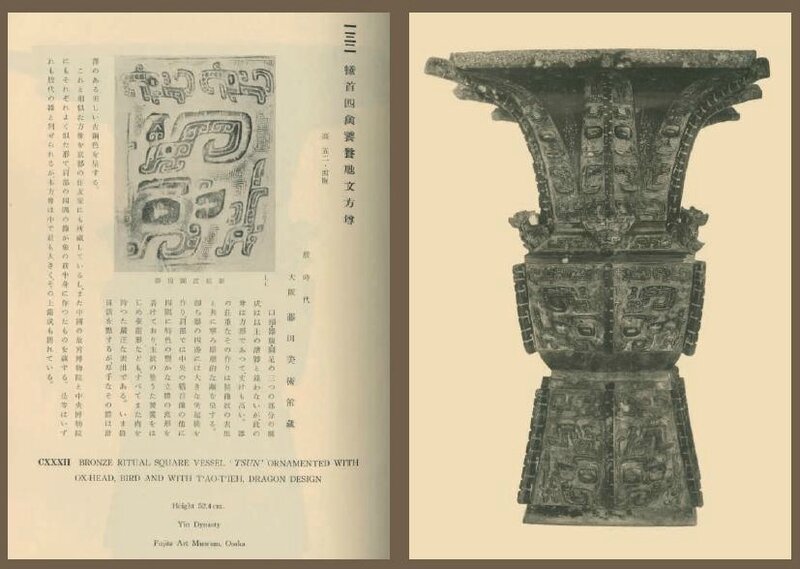

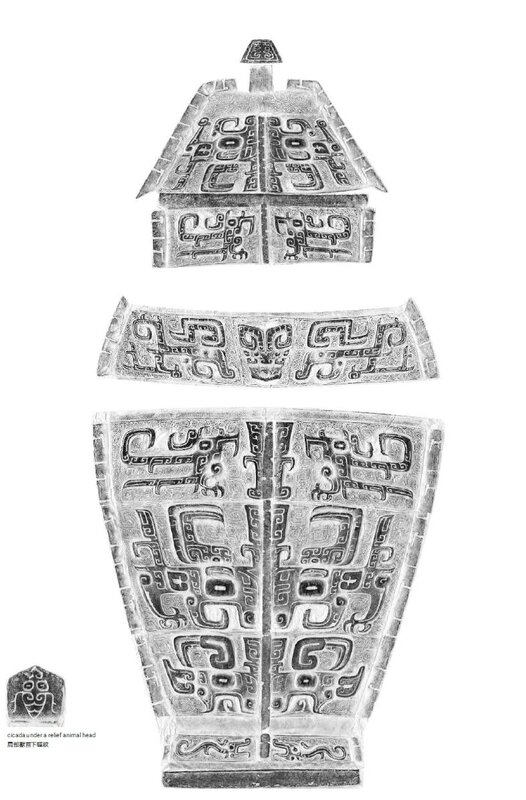

Lot 523. A magnificent and highly important bronze ritual wine vessel, fangzun, Late Shang Dynasty, Anyang, 13Th-11th century BC. Estimate USD 6,000,000 - USD 8,000,000. Price realised USD 37,207,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The decoration on each of the four sides of the faceted vessel is arranged in horizontal registers divided by vertical notched flanges which are repeated at the corners. The main register of the tapering mid-section is cast with large taotie masks with dragon-shaped horns, each flanked by descending kui dragons on either side and below a narrow register of confronting kuidragons with elephant trunks. The high foot is similarly decorated with taotie masks below a narrow register of confronting kui dragons with hooked beaks. The canted shoulder has a band of confronting kui dragons centered by relief animal masks and separated by mythical birds crowned by monster masks with bottle horns on the corners, all below a flaring neck with a band of upright blades enclosing dispersed elements of taotie above pairs of confronting kui dragons. All of the decoration is cast in crisp relief and reserved on leiwengrounds. The surface has a smooth dark green patina with some areas of light malachite encrustation. 20 5/8 in. (52.4 cm.) high, gold and silver-inlaid wood stand, Japanese double wood box, Metal liner, inscribed with cyclical date gui hai year, corresponding to 1923

Provenance: Fujita Museum, Osaka, acquired prior to 1940.

Rubbing by Wu Libo.

Literature: Masterpieces in The Fujita Museum of Art, vol. 1: Arts and Crafts, Fujita Museum, Osaka, 1954, no. 77.

Chugoku In Shu dokiten (Exhibition of Chinese Bronzes from Yin and Zhou Dynasties), Nihon Keizai Shimbun Inc., Tokyo, 1958, no. 54.

Seiichi Mizuno, Bronzes and Jades of Ancient China, Tokyo, 1959, p. 85.

Kodai Chugoku Seidoki Meihinten (Exhibition of Masterpieces of Ancient Chinese Bronzes), Nihon Keizai Shimbun Inc., Osaka, 1960, no. 41.

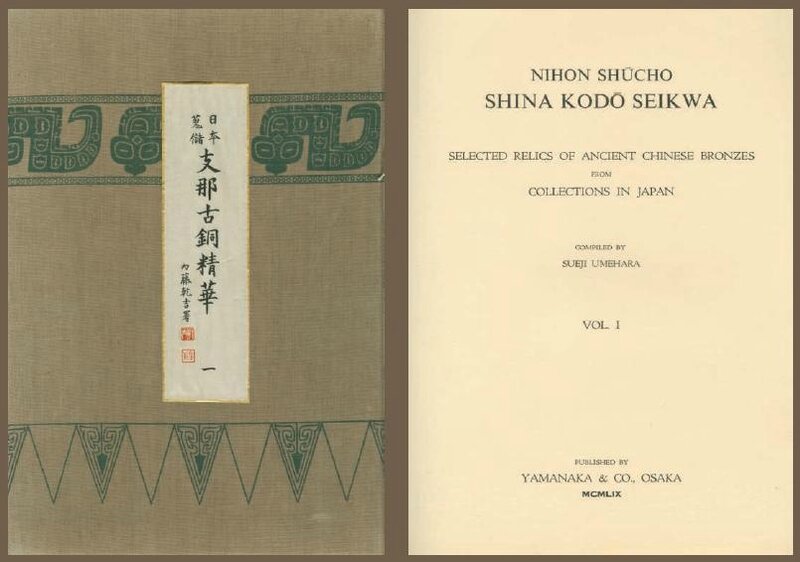

Sueji Umehara, Nihon shucho shina kodo seika (Selected Relics of Ancient Chinese Bronzes from Collections in Japan), vol. 2, Osaka: Yamanaka & Co., 1960, no. 132.

Shigeki Kaizuka, ed., Sekai Bijutsu Zenshu: Chugoku 1, Yin, Shu, Sengoku (Complete Collection of the World’s Art: China1 Yin, Zhou, and the Warring States), vol.12, Tokyo, 1962, no. 35.

Masterpieces in The Fujita Museum of Art, Fujita Museum, Tokyo, 1972, no. 92.

Minao Hayashi, In Shu jidai seidoki no kenkyu (Conspectus of Yin and Zhou Bronzes), vol. 1 (plates), Tokyo, 1984, p. 219, you jian zun no. 46.

Takayasu Higuchi, Jiro Enjoji, ed., Chugoku seidoki hyakusen (100 Selected Chinese Archaic Bronzes), Tokyo, 1984, no. 31.

The present fangzun as illustrated by Sueji Umehara, Nihon shu-choshinakodo-seika (Selected Relics of Ancient Chinese Bronzes from Collections in Japan), Osaka: Yamanaka & Co., 1960, vol. 2, no. 132.

Exhibited: Tokyo, Nihon Keizai Shimbun Inc., Chugoku In Shu dokiten (Exhibition of Chinese Bronzes from Yin and Zhou Dynasties), 25 November-7 December 1958.

Osaka, Nihon Keizai Shimbun Inc., Kodai Chugoku Seidoki Meihinten (Exhibition of Masterpieces of Ancient Chinese Bronzes), 30 August-11 September 1960.

Note: Square (fang) vessels had great significance to Shang ruling elites and are much more rare than their rounded-form counterparts. The first vessel type to be cast in square cross section is the ding, such as the massive early Shang fangding (100 cm. high) found in Duling, Zhengzhou city, illustrated in Shangyi yiyi sifang zhiji, Hefei, 2013, p. 61. Scholars have noted that the casting of fangding is more difficult than round ding and that massive fangding vessels were reserved for nobility of the highest rank and symbolize the royal power, (see ibid., p. 60). During the late Shang dynasty, a few other select vessel types were also made in a square shape, such as fangzun.

Fangzun of such a large size and with such fine casing such as the Fujita example are exceptionally rare. Two fangzun vessels of very similar form but decorated with dissolved elements of taotie in the mid and lower sections include one in the Sumitomo Collection, Kyoto, and one in the Hunan Provincial Museum, illustrated in Sen-oku Hakko: Chugoku kodoki hen, Kyoto, 2002, p. 60, no. 69, and ‘Min’ Fanglei and Selected Bronze Vessels Unearthed from Hunan, Shanghai, 2015, no.7, respectively. A pair of fangzun vessels of smaller size bearing Ya Zhi clan signs were found in Guojiazhuang M160, Anyang City, and are illustrated by Yue Hongbin ed., Ritual Bronzes Recently Excavated in Yinxu, Kunming, 2008, nos. 125, 126 (43.9 cm. high) and no. 127 (44.3 cm. high). It is interesting to note that the animal heads in relief on the shoulder of the two Ya Zhi fangzun are removable, unlike the sculptural figures on the Fujita fangzun which are fixed on the shoulder by casting. Compare, also, a pair of fangzun formerly in the Qing imperial collection and now separated, one in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in Bronzes Gallery of the Palace Museum, Beijing, 2012, no. 11, and the other in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, illustrated in Shang Ritual Bronzes in the National Palace Museum Collection, Taipei, 1998, no. 88. These two fangzun are more closely related to the Ya Zhi fangzun in shape and decoration and bear nine-character inscriptions: ya chou zhu si yi tai zi zun yi ('Zhusi from the Ya Chou clan made this ritual vessel for princes'). The Ya Chou was a clan active in the late Shang dynasty in modern day Shandong province. Between 1965 and 1966, archaeologists found the cemetery of the Ya Chou clan in Sufutun, Qingzhou City, Shandong province. One of the tombs in the Ya Chou clan cemetery is cross-shaped with four ramps, a format used for tombs of Shang kings. The National Palace Museum has two further fangzun bearing Ya Chou clan signs (See ibid., nos. 89 and 90). All three Ya Chou fangzun in the National Palace Museum are dated to the late Anyang period (12th-11th century BC). The projections on top of the flanges around the mid sections of the Ya Chou fangzun and the fact that their lower sections are cast without clay core extension holes indeed indicate a later date than the Fujtia fangzun.

Fu Hao fangzun, late Shang dynasty, 16 7 in. (43 cm.) high. Collection of the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. After Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji (The Complete Collection of Chinese Bronzes), vol. 3, Beijing, 1997, no. 108.

Si Qiao Mu Gui fangzun (one of a pair), late Shang dynasty, 22 in. (56 cm.) high. Collection of the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. After Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji (The Complete Collection of Chinese Bronzes), vol. 3, Beijing, 1997, no. 109.

One of the most remarkable features of the Fujita fangzun are the three-dimensional mythical bird-like creatures that adorn each corner of the shoulder. They feature prominent hooked beaks, wings, curled tails, and most notably bottle-horned monster masks that crown the birds’ heads. Similar bird-like creatures appear on the aforementioned Sumitomo fangzun, as well as in a small bronze zun wine vessel in the Art Institute of Chicago. (Fig. 1) The hybrid between mythical animal and real animal/bird is a common way of creating new motifs in Shang bronze art. The Shang people’s interest in hybrid animals can also be seen in the kui dragons with elephant trunks in the top band of the mid-section of the Fujita fangzun. In fact, the horns of the main taotie motif on the Fujita fangzun are replaced by pairs of bottle-horned kui dragons shown in profile. Similar depictions of taotie with dragon horns can be found on a hu vessel sold at Christie’s New York, 16 September 2010, lot 831, and a massive pou vessel in the Nezu Museum, illustrated in the Nezu Museum, Kanzo In Shu no seidoki, Tokyo, 2009, p. 25, no. 5.

Fig. 1. Bird-Shaped Wine Vessel, Shang dynasty (c. 1600-1050 BC), Lucy Maud Buckingham Collection, Art Institute of Chicago, 1936.139, The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY.

Lot 524. A magnificent and highly important bronze ritual wine vessel, fanglei, Late Shang Dynasty, Anyang, 13Th-11th century BC; 25 in. (63.5 cm.) high. Estimate USD 5,000,000 - USD 8,000,000. Price realised USD 33,847,500 © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The decoration on each of the four sides of the high-shouldered, tapering body is arranged in horizontal registers divided by vertical flanges which are repeated at the corners. The two lower registers are cast in relief with large taotie masks, one of which is centered by a D-shaped handle surmounted by an animal mask. In the register above, a forehead shield symbolizing a taotie mask is flanked by a pair of birds, which are repeated on the rectangular neck. The rounded shoulder is cast with pairs of dragons separated on two sides by an animal mask in high relief, and on the other two, narrower sides, with a pair of animal-mask-surmounted, D-shaped handles that suspend loose rings cast with four eye patterns. All of the decoration is cast in crisp relief and reserved on leiwengrounds. The surface has a dark green patina, gold and silver-inlaid wood stand, Japanese double wood box

Provenance: Fujita Museum, Osaka, acquired prior to 1940.

Rubbing by Li Zhi.

Literature: Masterpieces in The Fujita Museum of Art, vol. 1: Arts and Crafts, Fujita Museum, Osaka, 1954, no. 78.

Seiichi Mizuno, Bronzes and Jades of Ancient China,Tokyo, 1959, p. 80.

Sueji Umehara, Nihon shucho shina kodo seika (Selected Relics of Ancient Chinese Bronzes from Collections in Japan), vol. 1, Osaka, Yamanaka & Co., 1959, no. 18.

Shigeki Kaizuka, ed., Sekai Bijutsu Zenshu: Chugoku 1, Yin, Shu, Sengoku (Complete Collection of the World’s Art: China 1 Yin, Zhou, and the Warring States), vol. 12, Tokyo, 1962, no. 36.

Exhibition of Eastern Art: Celebrating the Opening of the Gallery of Eastern Antiquities, Tokyo National Museum, 1968, p. 67, no. 275.

Seiichi Mizuno, Asiatic Art in Japanese Collections: Chinese Archaic Bronzes, vol. 5, Tokyo, 1968, pl. 37.

Masterpieces in The Fujita Museum of Art, Fujita Museum, Tokyo, 1972, no. 435.

Exhibition of Ancient Chinese Art, Fujita Museum, Osaka, 1978, p. 3, no. 1.

Minao Hayashi, In Shu jidai seidoki no kenkyu (Conspectus of Yin and Zhou Bronzes), vol. 1 (plates), Tokyo, 1984, p. 291, lei no. 23.

Takayasu Higuchi, Jiro Enjoji, ed., Chugoku seidoki hyakusen (100 Selected Chinese Archaic Bronzes), Tokyo, 1984, no. 53.

The present fanglei as illustrated by Sueji Umehara, Nihon shu-cho shina kodo-seika (Selected Relics of Ancient Chinese Bronzes from Collections in Japan), Osaka: Yamanaka & Co., 1959, vol. 1, no. 18.

Exhibited: Tokyo National Museum, Exhibition of Eastern Art: Celebrating the Opening of the Gallery of Eastern Antiquities, 12 October to 1 December 1968.

Osaka, Fujita Museum, Exhibition of Ancient Chinese Art, Spring 1978.

Note: Fanglei are amongst the rarest, most imposing, and most majestic of Chinese archaic bronzes. The largest fanglei known appears to be the Min fanglei (88 cm. high), sold privately through Christie's New York in March 2014, and now kept in the Hunan Provincial Museum. See ‘Min’ Fanglei and Selected Bronze Vessels Unearthed from Hunan, Shanghai, 2015, no. 1. According to research by Xiao Taochu of the Hunan University and Wu Xiaoyan of the Hunan Provincial Museum, there are only 45 examples of Shang and Western Zhou fanglei, the majority of which are in major museums around the world. See Wenwu, 2016, no. 2, p. 58 and Appendix 1.

Shang and Western Zhou fanglei can be divided into three groups based on the arrangement of their decoration. The first type has whorl-cast bosses centered by relief animal masks and loop handles around the shoulder, such as an early Yinxu example without a cover found in Huayuanzhuang Dongdi M54, illustrated in Ritual Bronzes Recently Excavated in Yinxu, Kunming, 2008, p. 165; and an early Western Zhou example in the Shanghai Museum, illustrated by Wu Xiaoyan and Xiang Taochu, op. cit., p. 59, fig. 6. The second type has two narrow friezes of decoration on the shoulder and upper body and a band of taotie-filled blades pendent around the lower body, such as the fanglei formerly in the Sze Yuan Tang Collection, offered at Christie’s New York, 16 Sep 2010, lot 838; one with a Ya Yi clan sign, thought to have come from a royal Shang tomb at Xibeigang, Anyang, now in the Okada Museum of Art, Hakone, illustrated by Sueji Umehara in Nihon shucho shina kodo seika (Selected Relics of Ancient Chinese Bronzes from Collections in Japan), vol. 1, Osaka, 1959, no. 6; and another example in the Nezu Museum, illustrated ibid, no. 13. It is interesting to note that the Nezu example has taotie masks cast upright on its cover, whereas most of the taotie motifs cast on covers are inverted, as seen on the Fujita fanglei.

Bronze fanglei, late Shang dynasty, 20 7 in. (53 cm.) high. The Shanghai Museum Collection. After Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji (The Complete Collection of Chinese Bronzes), vol. 4, Beijing, 1998, no. 113.

Bronze fanglei, late Shang dynasty, 24 5 in. (62.5 cm.) high. The Sumitomo Collection, Kyoto. After Sen-oku Hakko: Chugoku kodoki hen, Kyoto, 2002, p. 97, no. 114.

Another view of the Sumitomo fanglei, late Shang dynasty. After Robert W. Bagley, Shang Ritual Bronzes in the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Cambridge, 1987, p. 106, fg. 132.

The third and most elaborate type has multiple friezes of kui dragons and taotie fully embellishing the body, such as the present vessel. Other known examples include two very similar fanglei, one in the Sumitomo Collection, Kyoto, illustrated in Sen-oku Hakko: Chugoku kodoki hen, Kyoto, 2002, p. 97, no. 114, and the other in the Nezu Museum, Tokyo, illustrated in the Nezu Museum, Kanzo In Shu no seidoki, Tokyo, 2009, p. 33, no.12; one without a cover in the Shanghai Museum, published extensively, including by Wen Fong, ed., The Great Bronze Age of China, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1980, no. 27; one with a Ya Chou clan sign in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in Zhongguo meishu quanji: gongyi meishu 4, Beijing, 1987, no. 126; and a Western Zhou example in the St. Louis Art Museum, illustrated by S. D. Owyoung in Ancient Chinese Bronzes in the Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, 1997, no. 24.

Lot 525. An extremly rare massive bronze ritual vessel and cover, pou, Late Shang Dynasty, Anyang, 13Th-11th century BC. Estimate USD 4,000,000 - USD 6,000,000. Price realised USD 27,127,500 © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The broad, rounded body is raised on a tall, slightly splayed foot crisply cast with three taotie masks formed by three pairs of elongated dragons confronted on heavy notched flanges. The lower register of the body is decorated with three large taotiemasks with bulging eyes, each flanked by small descending kuidragons, beneath a plain, narrow band and a wider band of dragons confronted on three animal masks on the wide shoulder. The domed cover is cast with three large upturnedtaotie masks centered and divided by heavy notched flanges, all beneath a tall segmented knob. Each band is cast in high relief and reserved on leiwen grounds. The surface has a silvery patina with areas of malachite encrustation.22 ½ in. (57.2 cm.) high, gold and silver-inlaid wood stand, Japanese double wood box

Rubbing by Wu Libo.

Provenance: Fujita Museum, Osaka, acquired prior to 1940.

Literature: Masterpieces in The Fujita Museum of Art, vol. 1: Arts and Crafts, Fujita Museum, Osaka, 1954, no. 79.

Sueji Umehara, Nihon shucho shina kodo seika (Selected Relics of Ancient Chinese Bronzes from Collections in Japan), vol. 1, Osaka, Yamanaka & Co., 1959, no. 10.

Masterpieces in The Fujita Museum of Art, Fujita Museum, Tokyo, 1972, no. 436.

Minao Hayashi , In Shu jidai seidoki no kenkyu (Conspectus of Yin and Zhou Bronzes), vol. 1 (plates), Tokyo, 1984, p. 313, pou no. 39.

Note: The pou form was popular during the middle Shang and early Yinxu periods, circa 14th-13th century BC. While most of the pou vessels were made withour covers and feature flat-cast decoration, the Fujita Museum pou, with its high-relief decoration, massive size, and a fitted cover, is one of the best of its type. It is also important to note that the Fujita Museum pou appears to be the third largest example among all the published examples of pou.

A covered pou of similar form and with similar layout of decoration, but of smaller size (50 cm. high), formerly in the collection of Fujita Tokujiro, is illustrated by Sueji Umehara in Nihon shucho shina kodo seika (Selected Relics of Ancient Chinese Bronzes from Collections in Japan), vol. 1, Osaka, 1959, no. 11. The Fujita Tokujiro pou is decorated with backward-turned kui dragons on the shoulder whereas the shoulder of the Fujita Museum pou is decorated with confronted kui dragons. The taotie on the body of Fujita Tokujiro pou are depicted without bodies, as are those on the Fujita Museum pou. A pou vessel in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology is almost identical to the Fujita Tokujiro pou but of even smaller size (45.7 cm. high). See Horace H. F., Jayne, ‘The Chinese Collections of The University Museum: A Handbook of the Principal Objects’, The University Museum Bulletin, 1941, no. 9, pp. 2-3. It is interesting to note that the Fujita Museum pou shares a very similar distinctive silvery patina with the University of Pennsylvania pou. A set of one large pou (47.6 cm. high) and a pair of smaller pou (34.2 and 33 cm. high) was found in the tomb of Fu Hao. See Tomb of Lady Hao at Yinxu in Anyang, Beijing, 1980, col. pl. 5 and pl. 29, respectively. The Fujita Tokujiro, the Fujita Museum and the University of Pennsylvania pou may also be seen as coming from the same set.

Bronze pou, late Shang dynasty, c. 1250 BC, 18 3 in. (47.6 cm.) high. The Henan Provincial Museum Collection. After Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji (The Complete Collection of Chinese Bronzes), vol. 3, Beijing, 1997, no. 76.

Fu Hao pou (one of a pair), late Shang dynasty, c. 1250 BC, 13 1 in. (34.2 cm.) high. Collection of the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. After Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji (The Complete Collection of Chinese Bronzes), vol. 3, Beijing, 1997, no. 73.

Another similar covered pou vessel of slightly smaller size (54 cm. high) from the J. Pierpont Morgan Collection, now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, is illustrated in ‘Asian Art at The Metropolitan Museum’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, summer 2015, no. 10. The Metropolitan Museum pou shares the same layout of decoration with the Fujita pou, although some details of decoration vary. The Metropolitan Museum pou has extra pairs of hooked-beaked birds below bodies of kui dragons on the shoulder and extra pairs of small kui dragons below bodies of taotie on the foot. The largest pou known is a covered pou vessel bearing a Ya Yi clan sign in the Nezu Museum (62.4 cm. high), illustrated in Kanzo In Shu no seidoki, Tokyo, 2009, p. 25, no. 5. The Ya Yi bronzes were reputedly from a royal Shang tomb at Xibeigang, Anyang city (see Sueji Umehara, op. cit., no. 5). The imposing size of the Ya Yi pou does indicate an extraordinary high status, however its surface decoration is flat-cast. The layout of decoration on the Ya Yi pou also differs from the other large pou vessels cited above, as it includes two additional decorative bands, one along the rim of the cover and one above the central taotie band on the body. Another covered pou (48 cm. high) is in the Idemitsu Museum of Art, Tokyo, illustrated in Selected Masterpieces from the Idemitsu Collection, vol. 1, Tokyo, 1986, no. 164. The cover of Idemitsu Museum pou has a narrow band of decoration similar to that on the cover of Ya Yi pou. A covered pou found in Huangcai township, Ningxiang county, Hunan province (42.5 cm. high), now in the Hunan Provincial Museum Collection, is illustrated in ‘Min’ Fanglei and Selected Bronze Vessels Unearthed from Hunan, Shanghai, 2015, pp. 138-147, no. 11. The Hunan pou features a sculptural coiled dragon as the knob of the cover, a trait which can also be found on the pou (60.7 cm. high) in the Tokyo National Museum, a gift of Mrs. Sakamoto Kiku, illustrated by Robert W. Bagley in Shang Ritual Bronzes in the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Cambridge, 1987, p. 108, fig. 136.

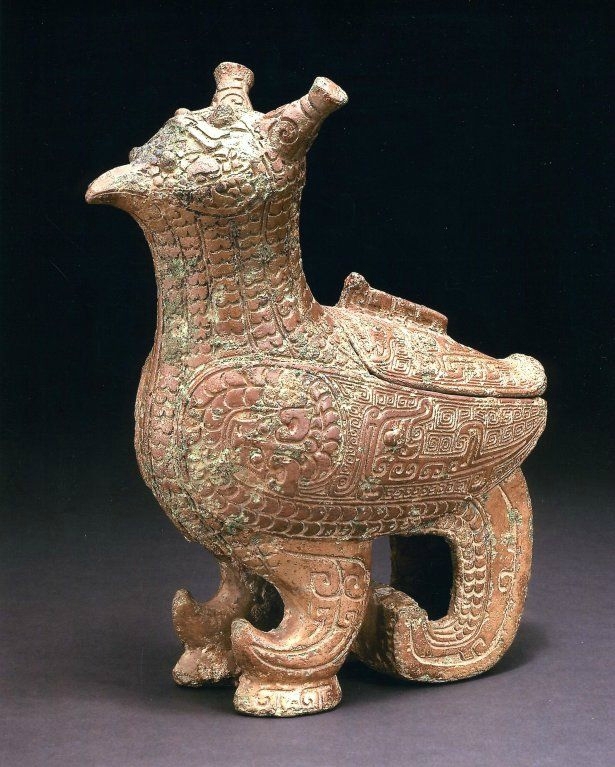

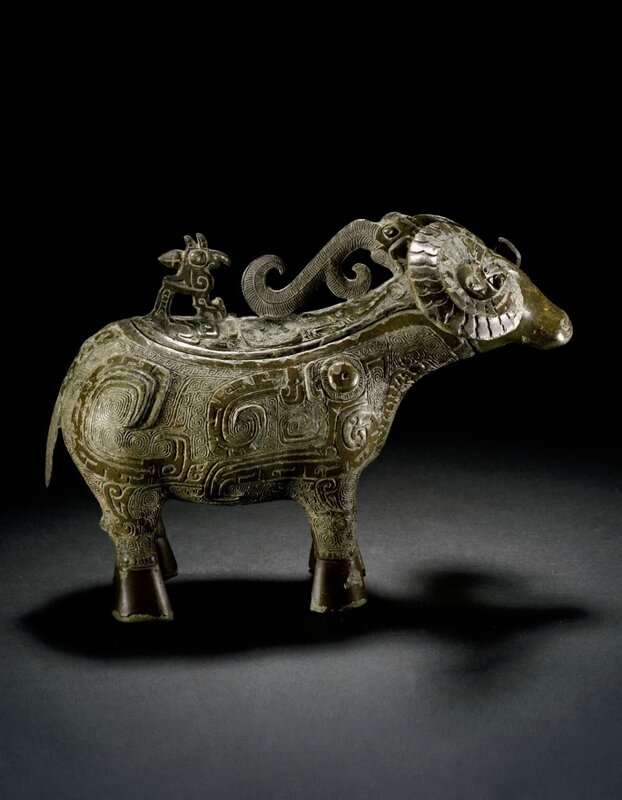

Lot 526. A highly important and extremly rare bronze ritual ram-form wine vessel, gong, Late Shang Dynasty, 13Th-11th century BC. Estimate USD 6,000,000 - USD 8,000,000. Price realised USD 27,127,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The animal is cast standing foursquare and fitted with an elongated cover ending in a ram's head with prominent C-shaped horns. The top of the cover is decorated with a pair ofkui dragons and a taotie mask and is set with a standing kuidragon with curling tail and a small standing bird at the center. The body is cast on each side with a large crested bird, its clawed foot extending downward onto the legs of the ram and its elongated tail curling around the ram's haunch. The chest of the ram is further decorated with a pair of crouching tigers. All of the decoration is cast in shallow relief and reserved on leiwengrounds. The patina is of yellowish-brown color. 8 5/8 in. (22 cm.) long, Japanese double wood box

Rubbing by Wu Libo.

Provenance: Fujita Museum, Osaka, acquired prior to 1940.

Literature: Masterpieces in the The Fujita Museum of Art, vol. 1: Arts and Crafts, Fujita Museum, Osaka, 1954, no. 74.

Chugoku In Shu dokiten (Exhibition of Chinese Bronzes from Yin and Zhou Dynasties), Nihon Keizai Shimbun Inc., Tokyo, 1958, no. 16.

Kodai Chugoku Seidoki Meihinten (Exhibition of Masterpieces of Ancient Chinese Bronzes), Nihon Keizai Shimbun Inc., Osaka, 1960, no. 18.

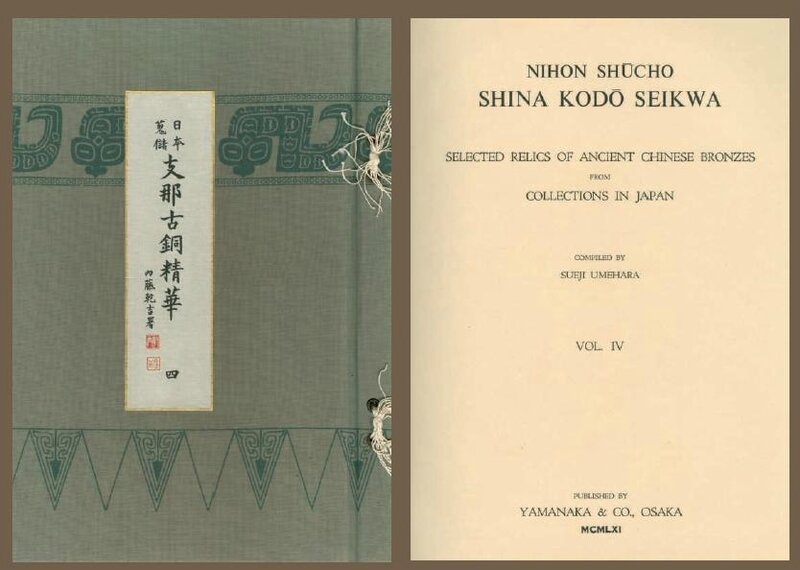

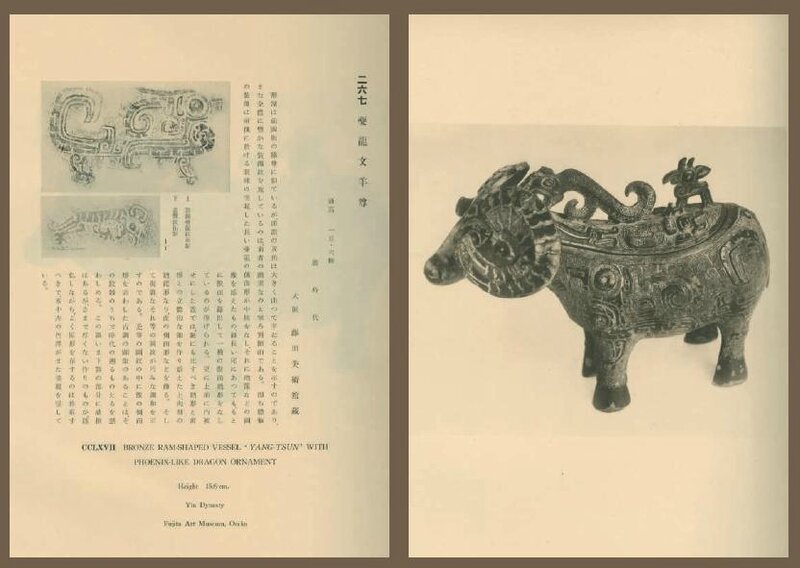

Sueji Umehara, Nihon shucho shina kodo seika (Selected Relics of Ancient Chinese Bronzes from Collections in Japan), vol. 4, Osaka, 1961, no. 267.

Shigeki Kaizuka, ed., Sekai Bijutsu Zenshu: Chugoku 1, Yin, Shu, Sengoku (Complete Collection of the World’s Art: China1 Yin, Zhou, and the Warring States), vol.12, Tokyo, 1962, no. 9.

Exhibition of Eastern Art: Celebrating the Opening of the Gallery of Eastern Antiquities, Tokyo National Museum, 1968, p. 62, no. 245.

Seiichi Mizuno, Asiatic Art in Japanese Collections: Chinese Archaic Bronzes, vol. 5, Tokyo, 1968, pl. 47.

Masterpieces in The Fujita Museum of Art, Fujita Museum, Tokyo, 1972, no. 91.

Minao Hayashi, In Shu jidai seidoki no kenkyu (Conspectus of Yin and Zhou Bronzes), vol. 1 (plates), Tokyo, 1984, p. 373, yi no. 24.

Takayasu Higuchi, Jiro Enjoji, ed., Chugoku seidoki hyakusen (100 Selected Chinese Archaic Bronzes), Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 1984, no. 20.

Rong Geng, Yin Zhou qingtongqi tonglun (Conspectus of Yin and Zhou Bronzes), Beijing, 1984 (reprinted in 2012),p. 50, pl. 74.

Robert W. Bagley, Shang Ritual Bronzes in the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Washington D.C., 1987, p. 420.

Zhongguo meishu quanji: gongyimeishu 4, qingtong (I), (Complete Collection of Chinese Art: Works of Art 4, Bronze 1), Beijing, 1990, p. 114, no. 123.

Zhu Fenghan, Gudai zhongguo qingtongqi (Ancient Chinese Bronzes), Tianjin, 1995, p. 195, fig. 3.34.4.

Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji: Shang (4) (Complete Collection of Chinese Bronzes: Shang), vol.4, Beijing, 1998, p. 89, no. 90.

Ma Chengyuan, Zhongguo qingtongqi (Chinese Bronzes), Shanghai, 2003, p. 233, fig. 13.

Ichirou Kominami, Kodai Chugoku Tenmeito Seidouki (Ancient China, Decree and Archaic Bronzes), Kyoto, 2006, p. 59.

The present ram-form gong as illustrated by Sueji Umehara, Nihon shu-cho shina kodo seikwa (Selected Relics of Ancient Chinese Bronzes from Collections in Japan), Osaka: Yamanaka & Co., 1961, no. 267.

Exhibited: Tokyo, Nihon Keizai Shimbun Inc., Chugoku In Shu dokiten (Exhibition of Chinese Bronzes from Yin and Zhou Dynasties), 25 November-7 December 1958.

Osaka, Nihon Keizai Shimbun Inc., Kodai Chugoku Seidoki Meihinten (Exhibition of Masterpieces of Ancient Chinese Bronzes), 30 August-11 September 1960.

Tokyo National Museum, Exhibition of Eastern Art: Celebrating the Opening of the Gallery of Eastern Antiquities, 12 October to 1 December 1968.

Note: Fully sculptural animal-form vessels are the rarest forms of Chinese archaic bronzes. The only complete Shang example that appears to have been offered at auction is a buffalo-form zun sold at Christie’s New York, 1 December 1988, lot 143. The Fujita gong is particularly charming for its thoroughly prepossessing ram form. Compare two other gong vessels of related form, but with highly stylized elephant heads: one in the collection of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington D.C., illustrated by Robert W. Bagley in Shang Ritual Bronzes in the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987, pp. 416-420, no. 74; the other excavated in 1983 from Zhangjia village, Yangxian county, Shaanxi province, illustrated in Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji (Compendium of Chinese Bronzes), Beijing, 1998, vol. 4, p. 90, no. 91. The ram had special prominence amongst southern bronzes, i.e. bronzes discovered in and likely to have been cast in the Yangzi River region. The most notable examples are the four-ram zun from Ningxiang, Hunan province, now in the National Museum of China, and two double-ram zun in the Nezu Museum, and the other in the British Museum (see ibid., nos. 115, 132, and 133 respectively).

Bronze gong vessel with pheonix pattern, late Shang dynasty, 8 5 in. (21.9 cm.) long. Collection of the Yangxian Museum. After Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji (The Complete Collection of Chinese Bronzes), vol. 4, Beijing, 1998, no. 91.

There are twelve other known Shang quadruped animal-shaped vessels, including four buffalos, three elephants, two mythical animals, one boar and one rhinoceros, all in museum collections. The Hunan Museum holds three quadruped animal vessels: a gong of buffalo form, a zun of elephant form, and another zun of boar form, all found in Hunan province and illustrated ibid., no. 87, 130, and 135; the latter two vessels were selected for the exhibition ‘Min’ Fanglei and Selected Bronze Vessels Unearthed from Hunan, Shanghai Museum, 2015, cat. nos. 8 and 9. The Shanghai Museum holds a quadruped animal gong, with a later-made cover copied after the cover of the Hunan buffalo-form gong, illustrated by Chen Peifen in Xia Shang Zhou qingtongqi yanjiu (Research of the Xia Shang Zhou Bronzes), Shanghai, 2004, pp. 336-337, no. 163. A buffalo-form zun inscribed with a two-character clan name, Ya Chang, was found in the Huayuanzhuang Dongdi M54, and is illustrated by Yue Hongbin ed., Ritual Bronzes Recently Excavated in Yinxu, Kunming, 2008, pp. 158-161. A buffalo-form gong, but lacking surface decoration, is in the Harvard Art Museums Collection, Cambridge, and illustrated in Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji (The Complete Collection of Chinese Bronzes), Beijing, 1998, vol. 4, no. 89. Another plain buffalo-form gong is illustrated by Sueji Umehara in Nihon shucho shina kodo seika (Selected Relics of Ancient Chinese Bronzes from Collections in Japan), vol. 4, Osaka, 1961, no. 266. An elephant-form zun with a cover surmounted by a small elephant is in the collection of the Freer Gallery, Washington D.C., and illustrated ibid, no. 129. Another elephant-form zun, but of unusually large size is in the collection of the Musée Guimet, Paris, illustrated ibid, no. 131. A pair of mythical horned animal gong found in the Fuhao tomb in Anyang city is illustrated in the Tomb of Lady Hao at Yinxu in Anyang, Beijing, 1980, fig. 40 and 41, col. pl. 9. A rhinoceros-form zun with a lengthy inscription dating it to the reign of the last Shang king is in the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco and is illustrated in Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji (The Complete Collection of Chinese Bronzes), Beijing, 1998, vol. 4, no. 134.

The Fujita gong is exceptional in its naturalistic sculptural quality, as well as being fully embellished with fantastic animals. Such naturalism can rarely be found in early Chinese bronze art, which is characterized by an overriding interest in invented motifs and articulated designs. The Fujita gong in contrast captures various anatomical features of a ram, such as the undecorated naturalistic head, which features a slightly up-turned muzzle with a pair of ‘comma’-shaped nostrils, prominent cheekbones, eyes with elongated orbits, leaf-shaped ears, and horns with parallel ridges. Compared with the Fujita gong, the profile of the ram heads on the four-ram zun is quite flat and the ram heads on both double-ram zun are degraded into cone-shapes, which make them far removed from the lifelikeness of the Fujita gong. Another extraordinary anatomical feature on the Fujita gong can be seen in the rendering of the fetlock on the ram’s rear legs. The naturalism of this gong is further enhanced by the curved silhouette of the body, which convincingly conveys the three-dimensional volume of the animal.

The Shang bronze craftsmen’s creativity went beyond mere representation. One trait denoting the Fujita gong as a sacred creature rather than a real animal can be found in the diamond-shaped pattern on the forehead of the ram. This very symbol appears ubiquitously on the forehead of taotie, the main theriomorphic motif on Shang/Zhou bronzes. What distinguishes the Fujita gong further from a real animal is the pantheon of mythical creatures on the surface of the vessel. Both sides of the ram’s body are embellished with large crested birds with clawed foot extending downward onto the legs and their elongated tail curling around the haunches. The cover which forms the ram’s back is further decorated with dragons and a taotie, and is surmounted by a kui dragon and a bird. The standing kui dragon has striated decoration that is typical of southern bronzes. Similar dragons can be found on the aforementioned Hunan elephant zun, and on the elephant zun vessel in the Freer Gallery, Washington D.C. Also notable is the tiger motif filling the space on the ram’s chest. Tigers were a popular motif in southern China, and appear on top of the handles of many ding vessels found in Xingan county, Jiangxi province (see Shangdai Jiangnan [The Southern Land of Shang Dynasty], Beijing, 2006, pp. 30-34, 38-41, 162-163, 166-168, etc.). A vertically-oriented tiger, like that on the chest of the Fujita gong, can also be seen embellishing the chest of the Hunan elephant vessel. Tigers were also used as surface decoration on Anyang bronzes, particularly during the early Yinxu period, such as the previously discussed Ya Chang buffalo-form zun and the Fu Hao yue axe, illustrated in Tomb of Lady Hao at Yinxu in Anyang, Beijing, 1980, col. pl. 13. The use of the tiger motif in Anyang is believed to have been influenced by southern bronzes.

Chinese Paintings

The collection of the Fujita Museum includes several important Chinese paintings and calligraphy, most from the Song and Yuan dynasties. Highlights amongst these are these is the six handscrolls that were formerly part of the collection of the Qianlong Emperor (1711-1799), as evidenced by his collector’s seals and their inclusion in his official catalogue, the Shiqu Baoji. The Qianlong Emperor’s collection was one of the largest and finest ever assembled in world history.

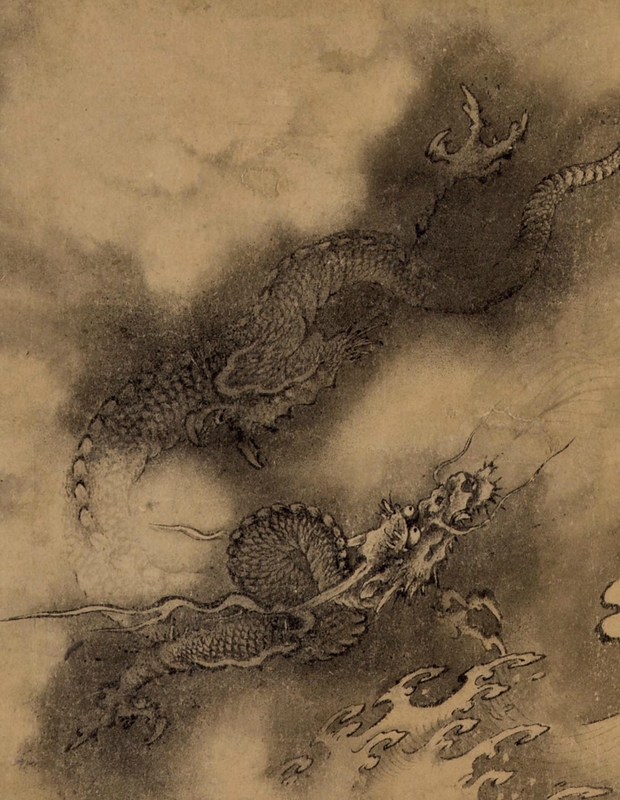

Six Dragons, attributed to the Song-dynasty painter Chen Rong (active ca. 13th century), presents a visually impressive image of six dynamic and muscular dragons amidst swirling mists and turbulent water. Although a highly educated and ambitious government official, Chen Rong’s greatest success came for his fabulous paintings of dragons.

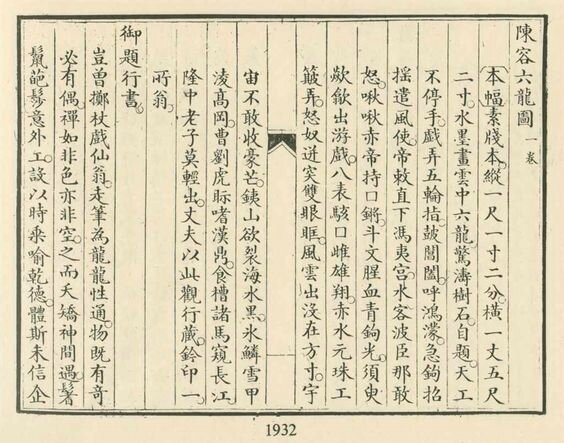

Lot 507. Chen Rong (active ca. 13th century) as catalogued in Shiqu Baoji, Six Dragons. Handscroll, ink on paper. Estimate: $1,200,000 - 1,800,000. Price realised USD 48,967,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

Painting: 13 ½ x 173 3/8 in. (34.3 x 440.4 cm.)

Calligraphy: 13 7/8 x 32 5/8 in. (35.1 x 82.8 cm.)

Inscribed, with one seal of the artist

Colophon by Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799), with two seals

Dated mid-spring, wuxu year (1778)

Colophons by Yu Minzhong (1714-1779), with two seals; Liang Guozhi

(1722-1786), with two seals; Wang Jie (1725-1805), with two seals; Dong Gao

(1740-1818), with two seals; Jin Shisong (1730-1800), with two seals; and

Chen Xiaoyong (1715-1779), with two seals

Thirty-four collectors’ seals including fourteen of Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799),

one of Emperor Jiaqing (1760-1820), nine of Zhuang Husun (17th century),

two of Prince Yixin (1832-1898)

Literature: Emperor Gaozong, Shiqu Baoji Xubian, 1793, Facsimile reprint, Taipei, National Palace Museum, 1971, p. 1932.

Suzuki Kei, Comprehensive Illustrated Catalog of Chinese Paintings: Japanese Museums, University of Tokyo Press, 1983, vol. 3, JM14-0023.

Note: Scholar-oficial painter Chen Rong is best known for his paintings of dragons. Since ancient times, dragons have been associated in China with rain and water and since the Han period have been a symbol of the emperor. Their connection with water is expressed here by the watery environment of clouds, mist, and waves in which they bend and twist. Not only did the artist employ wet ink and dark tones in this painting, but he also used a method of spraying ink across the surface to heighten the moist efect. As discussed by Jennifer Purtle in “The Pictorial Form of a Zoomorphic Ecology: Dragons and Their Painters in Song and Southern Song China,” the connection between Chen Rong’s paintings and rain was not just symbolic but his pictures were efectively used to summon rain as a part of rituals (in Jerome Silbergeld and Eugene Y. Wang, ed., The Zoomorphic Imagination in Chinese Art and Culture, Honolulu, 2016, pp. 253-288). Moreover, the strong contrasts and intermingling in this painting of light and dark, empty and densely painted, and dragons that are dynamic and ones that quietly, echo these creatures’ Daoist associations.

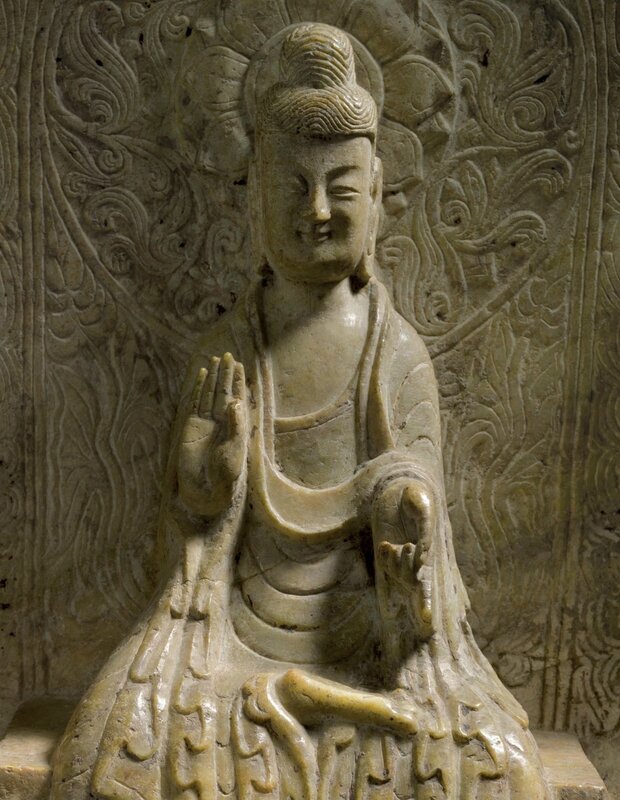

Buddhist Sculpture

The Fujita Museum sale also includes three important early Buddhist sculptures— a testament to Fujita Denzaburō’s interest in preserving Buddhism in Japan. Amongst the Buddhist highlights is a superbly carved marble stele featuring at the center a seated Buddha, probably the historical Buddha Shakyamuni. The Buddha is flanked on either side by a standing bodhisattva, each with his hands clasped before his chest in anjalimudra, a gesture indicating veneration. A roaring lion crouches at the foot of each bodhisattva. The figures are set before an intricately embellished lotus-petal-form mandorla and are raised on a table-like plinth bearing an inscription dating it to the second year of Xiaochang (AD 526) of the Northern Wei dynasty.

Lot 529. A rare and important dated marble buddhist triad, Northern Wei Dynasty (AD 386-534), dated second year of Xiaochang, corresponding to AD 526. Estimate: $600,000 - 800,000. Price realised USD 5,847,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The Buddha is depicted seated at the center with his right hand raised in abhaya mudra and his left in varada mudra. He is dressed in heavy robes that fall in voluminous folds below the ankles, and his head is framed by a lotus nimbus. The Buddha is flanked by two bodhisattvas with their hands held in anjali mudra, standing on lotus blossoms behind seated lions. The group is backed by an aureole intricately carved with foliage and flame motifs, and is raised on a four-legged base carved with a barbed edge on the front. An inscription on the front of the base provides the name of the monk, Xianxing, who commissioned the work and a date corresponding to AD 526.

23 7/8 in. (60.6 cm.) high, wood stand, Japanese wood box

Provenance: Fujita Museum, Osaka, acquired prior to 1940.

Literature: Masterpieces in The Fujita Museum of Art, Fujita Museum, Tokyo, 1972, no. 208.

Yomiuri Shimbun, East Currents of Wisdom: Great Oriental Art Exhibition, Kyoto, 1977, no. 22.

Jin Sheng, Zhongguo lidai jinian foxiang tudian (Catalogue of Dated Chinese Buddhist Sculptures), Beijing, 1994, no. 125.

Jin Sheng, Catalogue of Treasures of Dated Buddhist Sculpture in Overseas Collections Including Hong Kong and Taiwan, Shanxi, 2007, p. 49.

Exhibited: Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, East Currents of Wisdom: Great Oriental Art Exhibition, 1977, no. 22.

Lonquan Celadon

Amongst the other Chinese works from the Fujita Museum Collection are three large and impressive Longquan vessels exhibiting the luminous subtle green glaze with jade-like luster for which the Longquan kilns are so famous. Dating to the Yuan-Ming dynasties, these vessels have considerable presence and it is likely they were intended for display, rather than common use.

The large Yuan dynasty ‘phoenix-tail’ vase from the Fujita Collection is of elegant form and bears graceful sprig-molded peony sprays and scrolls. The glaze is especially fine and even, and of the ideal bluish-green tone much admired in China and in other parts of Asia.

Lot 501. A superb large carved and molded Longquan celadon ‘phoenix-tail’ vase, Yuan dynasty, 14th century; 24 5/8 in. (63.2 cm.) high. Estimate USD 200,000 - USD 300,000. Price realised USD 727,500 © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The heavily potted vase has a round body applied with a sprig-molded peony scroll above two bands of carved overlapping lotus petals. The trumpet-form neck is applied with further peony sprays beneath horizontal ribbed bands on the underside of the flaring mouth rim, and the whole is covered with a thick glaze of bluish sea-green tone with the exception of the unglazed foot, Japanese wood box

Provenance: Fujita Museum, Osaka, acquired prior to 1940.

Literature: Masterpieces in The Fujita Museum of Art, vol. 2: Tea-ceremony Implements, Fujita Museum, Osaka, 1954, no. 45.

Masterpieces in The Fujita Museum of Art, Fujita Museum, Tokyo, 1972, no. 339.

Note: Amongst the Chinese treasures from the Fujita Museum Collection is a small group of monumental Longquan celadon vessels bearing the subtle green glazes characteristic of the wares of the Yuan and early Ming dynasties. These large wares have considerable presence and it is likely that they would have been for display, rather than common use.

The Longquan glaze was perfected during the Southern Song period, but as the Yuan dynasty progressed production rose, so that some 300 kilns were active in the Longquan area from the Dayao, Jincun and Xikou kiln complexes in the west to those on the banks of the Ou and Songxi rivers. These rivers facilitated the transportation of the ceramics to other parts of China as well as to the ports of Quanzhou and Wenzhou, for shipment abroad. New shapes and styles of decoration were introduced, and pieces of impressive size, such as those from the Fujita Museum, began to be made at the Longquan kilns. While some of the larger pieces, such as the large dishes, were initially inspired by the requirements of patrons from Western Asia, other large forms were appreciated by patrons in both West and East Asia. These latter forms included large 'phoenix-tail' vases and large covered jars. Both of these forms were popular in Japan, as well as China itself. A Longquan lidded celadon jar was found in the grave of Kanesawa Sada-aki (金沢貞顕1278-1333) on the grounds of the Shomyo-ji temple (称名寺). The Shomyo-ji temple, which is believed to have been set up by Hōjō Sanetoki (北条実時1224-76) during the Kamakura period, still has in its collection two large Longquan celadon vases and a large incense burner with applied relief decoration. Other major Japanese temples, such as the Engaku-ji (円覚寺) and Kencho-ji (建長寺) at Kamakura also still use celadon vases preserved in the temples since the Kamakura (AD 1185-1333) and Muromachi (AD 1333-1573) periods.

The Fujita Yuan dynasty vase has an elegantly fared mouth and is decorated with bow-string lines around the upper part of the neck and the underside of the mouth. There is a band of elongated overlapping petals around the lower part of the body and foot. The main section of the neck and the upper part of the body bear sprig-moulded peony sprays and scrolls. The stems of the peony scroll are created using slip-trailing. The glaze is especially fne, with a rich translucent texture and a clear bluish-green tone, of the kind much admired in China and in other parts of Asia. Like the two other large Longquan vessels from the Fujita Museum in the current sale, this vase has been made using an ingenious technique which prevents the cracking and distortion of large forms during fring. The base inside the foot ring of the vase has been cut away, leaving a sizeable hole. This hole has been covered from the interior by a saucer-shaped element. Both the area around the hole and the saucer itself were covered with glaze. During fring, as the body material of the vase expanded or contracted, the saucer was able to foat on the glaze and, after fring, the glaze solidifed, sealing the saucer in place.

A similar vase, also with relief peony decoration was excavated from a site to the east of Huhehot in Inner Mongolia (illustrated in Wenwu, 1977, vol. 5, p. 76). A Jun ware censer in ding form, which was excavated from the same site, was incised with a cyclical date of the ninth month of the jiyou year, which has been calculated by the archaeologists as corresponding to AD 1309. A smaller vase of similar shape, but with bow-string lines around the whole of the neck and sprig-moulded peony scroll only around the upper half of the body, was salvaged from the wreck of a Chinese trading vessel which foundered of the Sinan coast of Korea on its way from Ningbo in China to Kamakura in Japan in AD 1323 (illustrated in Special Exhibition of Cultural Relics Found of Sinan Coast, Seoul, 1977, colour plate 10). A pair of taller vases with similar decoration to the Fujita vase are today still preserved in the collection of the Daitoku-ji temple in Kyoto (illustrated in Daitoku-ji no meiho (大德寺の名 宝), Kyoto, 1985, no. 95). A somewhat taller vase with similar decorative scheme to the Fujita vase, but with carved foral decoration (rather than sprig-moulded), is in the Percival David collection, London (illustrated by R. Scott in Imperial Taste: Chinese Ceramics from the Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, San Francisco, 1989, p. 50-51, no. 24). (Fig. 1) This latter vase bears an inscription, incised under the glaze around the inner lip of its mouth, which reads:

栝倉剱川流山萬安社居奉三寳弟子張進成燒造大花瓶壹雙捨入覺林院大法堂佛前永充供養祈福保安家門 吉慶者泰定四年丁卯嵗仲秋吉日謹題

‘Zhang Jincheng of the village of Wan’an at Liu mountain by the Jian river in Guacang, a humble disciple of the Precious Trinity [of Buddhism], has made a pair of large fower vases to be placed before the Buddha in the Great Dharma Hall at Juelin Temple, with [pledges for] eternal support and prayers for the blessings of good fortune and peace for his family and home. Respectfully inscribed on an auspicious day in the eighth month of dingmao, the fourth year of the Taiding period [AD 1327].’

Fig. 1. Large dated temple vase, Yuan dynasty, dated around AD1327, Longquan ware, PDF. 237. © Sir Percival David Collection/courtesy the Trustees of The British Museum.

It seems likely, in view of the dates associated with the Inner Mongolian fnd, the Sinan wreck, and the inscribed date on the Percival David vase, that the Fujita vase dates to the period circa AD 1300-1330.

A very slightly taller vase of the same shape and with very similar decoration is in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago (illustrated by Y. Mino and K. R. Tsiang in Ice and Green Clouds – Traditions of Chinese Celadon, Indianapolis, 1987, p. 201, no. 81).

Lot 502. A Longquan celadon carved jar and cover, Yuan dynasty, 14th century; 12 ¾ in. (32.4 cm.) high. Estimate USD 100,000 - USD 150,000. Price realised USD 787,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The jar is carved around the sides with lotus scroll above a border of upright lotus petals. The lotus leaf-form cover is carved with two lotus flowers joined by intertwined tendrils around the stem-form finial. The whole is covered with a glaze of attractive pale bluish celadon tone ending at the foot, revealing an unglazed area which has fired dark orange and cants inward towards the inset base, Japanese wood box

Provenance: Fujita Museum, Osaka, acquired prior to 1940.

Literature: Masterpieces in The Fujita Museum of Art, Fujita Museum, Tokyo, 1972, no. 35.

Nihon Toji no Bi to Genryu (Beauty and Origin of Japanese Ceramics), 90th Special Exhibition, Osaka Municipal Museum, 1981, p. 29, no. 18.

Treasures of the Fujita Museum: The Japanese Conception of Beauty, The Fujita Museum, Tokyo, 2015, p. 180, no. 103.

Exhibited: Nihon Toji no Bi to Genryu (Beauty and Origin of Japanese Ceramics), 90th Special Exhibition, Osaka Municipal Museum, 29th April-7th June 1981.

Treasures of the Fujita Museum: The Japanese Conception of Beauty, The Fujita Museum; Suntory Museum of Art, 5 August-27 September 2015; Fukuoka Art Museum, 6 October-23 November 2015.

Note: The large Yuan dynasty lidded jar from the Fujita Museum is rare both for its size and the depth of its relief-carved decoration. Such jars with lotus-leaf shaped lids were made at the Longquan kilns from the Song dynasty, through the Yuan dynasty and into the Ming dynasty. A taller, undecorated jar of this form was excavated in 1974 from a Yuan dynasty tomb in the Yuanyichang (園藝場) area of Dongxi (東溪), Jianyang county (簡陽縣), Sichuan province. Although the tomb is dated to the Yuan dynasty, the archaeologists believe that the jar dates to the Southern Song dynasty (illustrated in Longquan Celadon – The Sichuan Museum Collection (龍泉青瓷), Macau, 1998, pp. 134-5, no. 38).

An undecorated lidded jar dating to the Yuan dynasty was excavated in 1975 at Yi’niao city 義鳥市, Zhejiang province (illustrated by Zhu Boqian (朱伯謙) (ed.) in Celadons from Longquan Kilns (龍泉窰 青瓷), Taibei, 1998, p. 196, no. 171). A smaller Ming dynasty lidded jar of this form, with carved foral decoration, was excavated in 1955 in Yujing village in Bazhong county, Sichuan province (illustrated in Longquan Celadon – The Sichuan Museum Collection, op. cit., pp. 162-3, no. 55). A further Ming dynasty jar with carved decoration including the four characters qing xiang mei jiu (清香美酒) is in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing (illustrated in Celadons from Longquan Kilns, op. cit., p. 262, no. 247).

Like the Fujita jar, the jars from the Yuan and Ming dynasties have saucer-shaped, separately-applied, bases, while the Southern Song jar has a fat fxed base. There are also a number of similar jars in the collection of the Topkapi Saray in Istanbul, some of which are plain, some with ribbed decoration and one (not missing its lid) with foral scrolls carved around the upper body (illustrated by in J. Ayers and R Krahl, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, vol. 1, Historical Introductions, Yuan and Ming Dynasty Celadon Wares, London, 1986, pp. 292-3, nos. 212-216, and colour plate on p. 215).

Lot 503. A rare massive carved Longquan celadon ‘phoenix-tail’ vase, Ming dynasty, 15th century;

26 5/8 in. (67.8 cm.) high. Estimate USD 100,000 - USD 150,000. Price realised USD 295,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The heavily potted, ovoid body is carved with a wide band of peony scroll in various stages of bloom around the shoulder on a brushed ground, above a band of lightly carved peony scroll and a band of upright lotus petals around the base. The trumpet neck is carved with a further narrow band of lotus scroll between bow-string borders and below encircling bands. The whole is covered with a glaze of rich sea-green tone except for the unglazed foot ring and separately-made recessed base, wood stand, Japanese wood box

Provenance: Fujita Museum, Osaka, acquired prior to 1940.

Literature: Treasures of the Fujita Museum: The Japanese Conception of Beauty, The Fujita Museum, Tokyo, 2015, p. 178, no. 101.

Exhibited: Treasures of the Fujita Museum: The Japanese Conception of Beauty, The Fujita Museum; Suntory Museum of Art, 5 August-27 September 2015; Fukuoka Art Museum, 6 October-23 November 2015.

Note: In the early Ming dynasty the celadon-glazed wares from the Longquan kilns remained popular, both within China and as export wares to other parts of Asia. It is also clear that some of the ceramics made at the Longquan kilns were being made for the court, under the supervision of government oficials sent from the capital. Signifcantly, juan 194 of the Da Ming Huidian (大明會典) states that in the 26th year of the Hongwu reign [AD 1393] some imperial wares were fred at the Rao and Chu kilns – i.e. at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi and at the Longquan kilns of Zhejiang.

In volume one of the Ming Xianzong Shilu (明憲宗實錄) it is noted that Emperor Xianzong ascended the throne in the eighth year of the Tianshun reign [AD 1464] and after the Chenghua reign began in the following year, an amnesty was declared. It was also noted that the oficials sent by the government to supervise ceramic production at the Yaozhou kilns of Jiangxi province and the Chuzhou kilns of Zhejiang province were required to return to the capital as soon as they received the imperial edict. Of the ceramics in production, those which had been completed should be registered, and work on those which had not been completed should cease. Failure to comply with the edict would be regarded as a crime. This makes it clear that there was oficial production at the Longquan kilns as late as AD 1465 - the beginning of the Chenghua reign.

The tall Ming dynasty Longquan celadon vase from the Fujita Museum is a rare example of a 'phoenix tail' vase dating to the 15th century. It has an elaborate peony scroll carved around the shoulders and the upper part of the body, while a band of slender petals encircles the foot. The vessel has a glaze that is slightly more yellowish in tone than that seen on the Yuan dynasty Fujita vase, which is typical of Longquan wares of the early Ming period. As in the case of the Yuan Longquan vase from the Fujita collection, before glazing the Ming dynasty vase, a hole was cut into the base, in order to allow the vessel to shrink during fring without cracking or distortion. A glazed saucer-shaped vessel was dropped into the hole, and would have been able to foat on the liquid glaze during fring. At the end of

the fring, the saucer was held in place by the solidifed glaze. The saucer used in this case is unusual, in that it is not fully glazed, but nevertheless seals the hole successfully.

There is a very similar vase of the same height in the collection of Sir Percival David, London (see Illustrated Catalogue of Celadon Wares in the Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, London, 1997, p.35, no.238). (Fig. 2) The Percival David vase shares the same decorative scheme as the Fujita vase, including the protruding line at the junction of lower body and shoulder, and also the two relief lines around the foot. On the neck of the David collection vase is a panel with an open lotus blossom at the bottom and a lotus leaf at the top, which contains an inscription incised under the glaze. This reads:

景泰伍年福里鎮安社信人楊宗信喜捨恭入本寺供養□自身延壽者

‘In the ffth year of the Jingtai period [AD 1454], the believer Yang Zongxin of the village of Zhen’an in the district of Fuli respectfully ofers this [vase] to the local temple to be placed before the Buddha, with a prayer for long life.’

Fig. 2. Large dated temple vase, Ming dynasty, dated around AD1454, Longquan ware, PDF. 238. © Sir Percival David Collection/courtesy the Trustees of The British Museum.

The National Palace Museum, Taipei has in its collection another vase which is very similar to the Fujita and David collection vases. (Fig. 3) It too has a related protruding join line at the lower edge of the shoulder, and also a double band at the foot (see 主編蔡玫芬, 碧緑 : 明代龍泉窯青瓷 /Green – ongquan Celadon of the Ming Dynasty, Tsai Mei-fen (ed.), Taipei, 2009, pp. 158-9, no. 81 and front cover). The Taipei vase is slightly smaller than the Fujita vessel, and has been dated by the Museum to 1435-1460. It seems reasonable to assume that the Fujita Ming dynasty Longquan vase also dates to the mid-15th century.

The Longquanxian zhi (龍泉縣志) (Gazetteer of Longquan County) noted that:

成治以後 , 質粗色惡 , 難充雅玩矣

‘After the Cheng[hua] and [Hong]zhi reigns [AD 1465-1506], the form [of Longquan wares] became so crude and the colour so unappealing, that they were no longer ft for those of elegant tastes.’

The Fujita Ming vase, therefore, represents the last great period of Longquan celadon production, when vessels of impressive form and glaze were still made at these prestigious kilns for the court and other members of the elite.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F51%2F84%2F119589%2F122518624_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F42%2F87%2F119589%2F112989160_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F52%2F119589%2F112495720_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F12%2F27%2F119589%2F96148405_o.jpg)