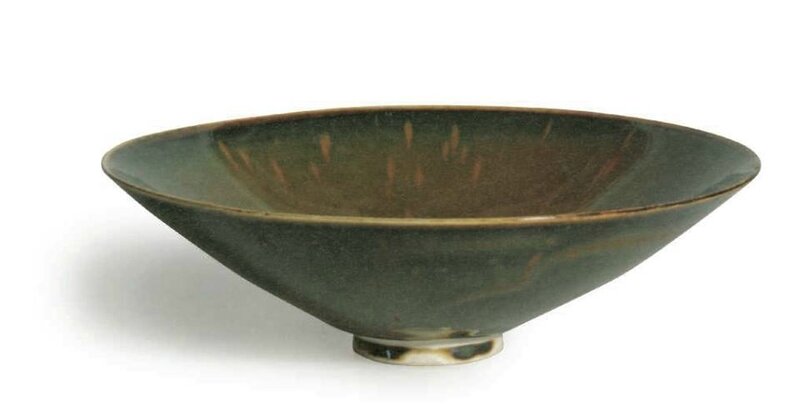

A highly important Ding russet-splashed black-glazed conical bowl, Northern Song dynasty (960-1127)

Lot 506. A highly important Ding russet-splashed black-glazed conical bowl, Northern Song dynasty (960-1127); 7 ½ in. (19 cm.) diam. Estimate On Request. Price realised USD 4,212,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2018

The bowl is delicately potted with wide, flaring sides, and is covered inside and out with a lustrous black glaze streaked with russet splashes which radiate from the center towards the mouth rim where the glaze thins to russet brown. The glaze on the exterior has some russet streaks and collects in thick drops on the foot ring exposing the fine white body, Japanese double wood box.

Provenance: Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Bernat.

Sotheby Parke Bernet New York, 7 November 1980, lot 91.

The Manno Art Museum, Osaka, no. 434.

Christie's Hong Kong, 28 October 2002, lot 515.

Sen Shu Tey, Tokyo.

Literature: The Currier Gallery of Art, Chinese Ceramics of the Sung Dynasty, Manchester, New Hampshire, 1959, no. 24.

Koyama Fujio, ed., Chinese Ceramics, One Hundred Selected Masterpieces from Collections in Japan, England, France and America, Tokyo, 1960, no. 53.

Mayuyama Junkichi, ed., Chinese Ceramics in the West, A Compendium of Chinese Ceramic Masterpieces in European and American Collections, Tokyo, 1960, no. 25.

Sekai Bijutsu Zenshu, vol. 16, China (5) Song Yuan, Tokyo, 1965, pl. 44.

Sir Harry Garner and Margaret Medley, Chinese Art, vol. III, London, 1969, p. 146, reel 20, no. 4.

Asia House Gallery, Masterpieces of Asian Art in American Collections II, New York, 1970, no. 32.

Margaret Medley, 'Simplicity and Subtlety in Chinese Ceramics', Apollo, London, July 1971, p. 452, fig. 8.

The Oriental Ceramic Society, The Ceramic Art of China, The Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 1971, no. 71, pl. 18.

Koyama Fujio, ed., Toki Koza (Lecture of Ceramics), vol. 6: Chugoku II So (China II Song), Tokyo, 1971, no. 79.

The Oriental Ceramic Society, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society 1969-1970 1970-1971, London, 1972, no. 71, pl. 48.

Koyama Fujio, ed., Toji Taikei (Compendium of Ceramics), vol. 38:Tenmoku, Tokyo, 1974, nos. 52 and 53.

The Manno Art Museum, Selected Masterpieces of the Manno Collection, Japan, 1988, pl. 93.

Tokyo National Museum, Special Exhibition: Chinese Ceramics, Tokyo, 1994, p. 110, no. 155.

Hasebe Gakuji (ed.), Chugoku no Toji (Chinese Ceramics), vol. 6: Tenmoku,Tokyo, 1999, no. 23.

Special Exhibition to Celebrate 100 year Anniversary of Tokyo Bijutsu Club, Tokyo, 2006, no. 13.

Sen Shu Tey, The Collection of Chinese Art - Special Exhibition ‘Run Through 10 Years’, Tokyo, 2006, pp. 50-51, no. 58.

Christie's, Christie's 20 Years in Hong Kong 1986-2006: Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art, Hong Kong, 2006, pp. 22-23.

Christie's, The Classic Age of Chinese Ceramics: An Exhibition of Song Treasures from the Linyushanren Collection, Hong Kong, 2012, pp. 34-35, no. 7.

Rosemary Scott, ‘Chinese Classic Wares from a Japanese Collection: Song Ceramics from the Linyushanren Collection’, Arts of Asia, March-April 2014, pp. 97-108, fig. 7.

Christie's, Christie's Thirty Years in Asia 1986-2016, Hong Kong, 2016, p. 131.

The present Ding ‘partridge feather’ bowl as illustrated in the Currier Gallery of Art, Chinese Ceramics of the Sung Dynasty, Manchester, New Hampshire, 1959, no. 24.

Exhibited: The Currier Gallery of Art, Chinese Ceramics of the Sung Dynasty, Manchester, New Hampshire, 11 April to 31 May 1959.

Nihon Keizai Shimbun, Chinese Ceramics, One Hundred Selected Masterpieces from Collections in Japan, England, France and America, Tokyo, 1960.

Asia House Gallery, Masterpieces of Asian Art in American Collections II, New York, 1970.

The Oriental Ceramic Society, The Ceramic Art of China, The Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 9 June to 25 July 1971.

Tokyo National Museum, Special Exhibition: Chinese Ceramics, Tokyo, 12 October to 23 November 1994.

Tokyo Bijutsu Club, Special Exhibition to Celebrate 100 year Anniversary of Tokyo Bijutsu Club, Tokyo, 2006.

Sen Shu Tey, The Collection of Chinese Art - Special Exhibition ‘Run Through 10 Years’, Tokyo, 2006.

Christie's, The Classic Age of Chinese Ceramics: An Exhibition of Song Treasures from the Linyushanren Collection, Hong Kong, 22 to 27 November 2012; New York, 15 to 20 March 2013; London, 10 to 14 May 2013.

THE ‘PARTRIDGE-FEATHER’ DING BOWL FROM THE LINYUSHANREN COLLECTION

Robert D. Mowry

Alan J. Dworsky Curator of Chinese Art Emeritus, Harvard Art Museums

Senior Consultant, Christie’s

Extraordinarily beautiful, the ‘partridge-feather’ Ding bowl from the Linyushanren Collection numbers among the few known examples

of black-glazed Ding ware, the rarest of Song-dynasty ceramics, rarer even than imperial Ru and Guan wares. In fact, this is the only such conical bowl known still to be in private hands. The bowl’s lustrous black glaze exhibits a well-dispersed pattern of short, vertically oriented, russet mottles and is traditionally termed a ‘partridge-feather’ glaze, or zhegubanyou 鷓鴣斑釉. Produced in the late eleventh or early twelfth century, this conical bowl displays all the hallmarks of classic black-glazed Ding ware, from its conical shape and white porcelain body to its thin walls and light weight, to it lustrous glaze and sparse embellishment, to its unglazed foot and partially glazed base.

Produced at a number of small kilns in Quyang county 河北省曲陽縣 (in central Hebei province, about 100 miles to the southwest of Beijing), Ding ware 定窯 is so named because Quyang county fell within the Dingzhou 定州 administrative district during the Northern Song period (960–1127). Collectors of the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties ranked Ding ware among the “fve great wares of the Song” 五大名窯, along with Jun 均窯, Ru 汝窯, Guan 官窯, and Ge 哥窯 wares. Celebrated for their ivory-hued porcelains, the Ding kilns also produced pieces with russet and black glazes, such as the magnifcent ‘partridgefeather’ conical bowl from the Linyushanren Collection. The Ding kilns supplied substantial quantities of ceramic ware to the palace in the Northern Song period, including black-glazed wares.

Characteristic of dark-glazed Ding bowls, this superb vessel is conical in shape, its form virtually identical to those of the three other darkglazed bowls securely assigned to the Ding kilns: the single bowl in the Percival David Foundation Collection, now on permanent loan to the British Museum (PDF.300) 1, and the two bowls in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums (1942.185.404 and 1942.185.411) 2 (Figs. 1 and 2). (A ffth bowl, now in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, may well belong to this small group of black Ding bowls, but it has not been available for direct study and comparison so it is not discussed here. 3) (Fig. 3) Each of these four bowls has a well-defned, fat foor approximately 2.5 cm in diameter from which the expanding walls rise; the foor corresponds to the base on the bowl’s underside. Although many white Ding bowls have gently rounded side walls, the white Ding bowls that correspond most closely to their dark-glazed congeners are the rare conical ones, such as the superb, Northern Song, white Ding conical bowl from Linyushanren Collection that sold at Christie’s, Hong Kong, on 30 May 2016, lot 3016 4. That conical bowl is the perfect white Ding counterpart to the Linyushanren, Harvard, and David Foundation black-glazed bowls; moreover, all fve bowls are similar in size, the four dark-glazed bowls ranging between 18.4 and 19 cm in diameter, the white Ding bowl measuring 21 cm in diameter. The walls of such Ding conical bowls, whether white- or black-glazed, often give the impression of being subtly bowed when viewed in profle; even so, their walls expand outward in an insistently ruler-straight line. Northern Song-period conical bowls in white Ding ware characteristically have delicately carved foral decoration, while those from a few decades later, and likely from the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), generally display molded decoration; 5 by contrast, black-glaze Ding bowls, when embellished, typically feature ‘partridge-feather’ mottles—that is, abstract, nonrepresentational decoration rather than the foral and other pictorial designs of white Ding ware. Like those of white Ding ware, the walls of dark-glazed Ding bowls are exceptionally thin, so that the vessels are very light in weight.

Fig. 1 Ding black-glazed conical bowl, Northern Song dynasty, 11th-12th century, 18.5 cm. diam. Collection of the Sir Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Fig. 2 Ding russet-splashed black-glazed conical bowl, Northern Song dynasty, late 11th-early 12th century, 18.9 cm. diam. Collection of the Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Ernest B. and Helen Pratt Dane. Photo: Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Fig. 3 Black-glazed ‘partridge feather’ conical bowl, Song-Jin dynasty, 12th-13th century, 20.3 cm. diam. Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei. Photo: © The Collection of National Palace Museum.

A rare and superbly carved Ding ‘Lotus’ conical bowl, Northern Song dynasty, 11th-12th century, from the Linyushanren Collection; 8 1/4 in. (21 cm.) diam. Sold for HK$7,480,000 ($967,783) at Christie's Hong Kong, 30 May 2016, lot 3016. © Christie's Image Ltd 2016.

Cf. my post: A rare and superbly carved Ding ‘lotus’ conical bowl, Northern Song dynasty, 11th-12th century

Taller and thicker than that of a white Ding bowl, the footring of the Linyushanren ‘partridge-feather’ bowl is similar in height and cut to those of the Harvard and David Foundation dark-glazed Ding conical bowls. White Ding bowls were fred upside down, their footrings fully glazed but their rims cleansed of glaze before fring. By contrast, dark-glazed Ding bowls were fred right side up, their rims fully glazed but their footrings wiped free of glaze before fring, permitting the bowls to rest on their footrings during fring without fear that melting glaze might fuse the bowls to their saggars. Inherently unstable because of the quantity of iron oxide added to achieve the dark color, black glazes in fact tend to run during fring, gravity pulling them downward as they melt in the heat of the kiln. That situation likely necessitated that the footrings of dark-glazed Ding bowls be a little taller than those of white Ding vessels. Indeed, dark-glazed Ding bowls from the Northern Song period often have localized areas of glaze on the exterior of the footring. Each of the Harvard bowls has areas of dark glaze on the exterior of its footring, as does the Linyushanren bowl. Some of the glaze on the exterior of the Linyushanren bowl’s footring resulted from teardrops of melting glaze descending during fring; other areas of glaze on the footring were accidentally deposited there during glaze application, however, as indicated by the small indentations in the glaze edge, the indentations occurring where the potter’s fngers interrupted the fow of the laze slurry as he gripped the footring while dipping the bowl into the slurry. In the succeeding Jin dynasty, potters at various kilns in northern China would refne their glaze formulae, creating dark glazes less prone to running during fring, so those slightly later pieces often exhibit very straight glaze edges and footrings completely free of glaze.

Like those of other dark-glazed, Ding conical bowls, the base of the Linyushanren bowl is partially glazed, and the glaze on the base boasts a fngerprint impression. 6 It is assumed that the fngerprint resulted from the manner in which the potter held the bowl when dipping it into the glaze slurry, the potter likely grasping the bowl tightly by its footring with his thumb and middle and ring fngers, but resting his index fnger on the base, leaving the fngerprint impression in the glaze there. Curious as it is, the fngerprint on the base is a standard feature of dark-glazed Ding bowls and likely refects no more than the consciously adopted and well practiced manner in which potters—or perhaps a single potter—held the bowls while dipping them.

The body of this bowl is porcelain and thus is vitrifed, due to the high temperature at which the bowl was fired. The smooth, fine-grained, pure-white porcelain body is visible on the unglazed areas of the footring and base. In addition, the body’s warm, ivory tone is clearly visible in a tiny, clear-glazed spot on the bowl’s interior just below the rim, a fring anomaly that is original to the piece; though glazed, the spot lacks the dark color of the surrounding glaze matrix as, for reasons of physics, the coloring agent that imparts the black color pulled away from that tiny spot during fring, leaving the spot coated with clear, colorless glaze through which the warm, ivory hue of the body is clearly visible. Composed almost entirely of kaolin, the body is visually identical in color and general appearance to that of white Ding ware; in fact, scientifc testing at Harvard revealed that the porcelain bodies of white- and dark-glazed Ding wares are identical. 7 In addition, like those of white Ding wares, the porcelain bodies of the Linyushanren and related blackglazed Ding bowls are translucent. Although the black glaze is seemingly opaque, light can be transmitted through the bowl’s thin walls in those areas where the glaze is naturally thin—immediately below the rim, for example.

Ding wares were fred in small, domed, or mound-shaped, kilns known in Chinese as mantouyao 饅頭窯, or “dumpling kilns”, the name denoting their similarity in shape to Chinese dumplings, or mantou. Although fired with wood in the late Tang (618–907) and Five Dynasties (907–960) periods—their earliest phase of development—the Ding kilns came to rely on coal as fuel beginning in the tenth century. When used to fuel kilns, coal generally gives rise to oxidation firing 氧化焰 with the result that white Ding wares have pale, honey-colored glazes rather than the very pale blue glazes of the fnest Xing wares 邢窯 or of the Qingbai wares 青白窯 produced at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province 江西省景德鎮. In addition, due to oxidation fring, the exposed body clay on Ding ware—whether the unglazed rims on white Ding ware or the unglazed footrings on darkglazed Ding ware—lacks the thin reddish skin that typically forms on areas of unglazed body clay on porcelains fred in a reducing atmosphere 還原焰, such as Qingbai and other wares from Jingdezhen, for example, which were fred in a reducing atmosphere in wood-fueled kilns.

Chinese potters had begun to experiment with high-fred ceramics coated with dark glazes, usually dark brown glazes, at least as early as the Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220) and had begun to use them with some regularity beginning in the fourth and fifth centuries, particularly at the Deqing 德清 and Yuhang 餘杭 kilns, near Hangzhou, in Zhejiang province 浙江省杭州市; however, it was only in the Tang dynasty that black glazes began their rise to prominence, especially at the Yaozhou Huangbaozhen kilns in Shaanxi province 陝西省銅川市耀州黃堡鎮窯 and at the Lushan Duandian 魯山段店, Jiaxian Huangdao 郟縣黃道, and Gongyi 鞏義 (previously called Gongxian 鞏縣) kilns, all in Henan province 河南省. The Lushan and Huangdao kilns produced light grey stonewares with dark brown glazes typically enlivened with variegated splashes of sky blue, while the Gongyi kilns occasionally produced small bowls with a white glaze on the interior and a black glaze on the exterior. In contrast to the dark-glazed wares made during the Tang at those several kilns,

all of which have matte surfaces, the Ding kilns produced wares with lustrous black glazes, which they did beginning in the eleventh century. In fact, the Ding kilns were the frst northern kilns to produce lustrous black glazes, setting the taste and the standard for dark-glazed wares subsequently produced at other northern kilns.

Ding russet-splashed black-glazed conical bowl (restored), late Northern Song dynasty. 19.5 cm. diam. Excavated from Ding kiln site in Quyang county, Hebei province. Collection of the Cultural Relics Institute Hebei Province. Photo: © Cultural Relics Institute, Hebei Province.

Despite generic use of the term “black glazes,” it should be emphasized that dark glazes made before the Qing dynasty are not truly black; rather, they are dark, chocolate-brown glazes that appear black in refected light. Such Song and Song-style glazes show their true brown color in bright light, in transmitted light, in areas where the glaze is thinner, as around the rims of the Linyushanren, Harvard, and Percival David Foundation bowls. Although fully glazed, the rims of these bowls appear light—sometimes caramel-brown, as in the Linyushanren and Harvard bowls, sometimes virtually white, as in the David Foundation bowl—because gravity caused the glaze to thin in those areas during fring, just as it also pulled away the coloring agent, so that the rims appear light. Unlike white Ding vessels, which traditionally were ftted with metal bands soon after fring to conceal the unglazed rims, dark-glazed Ding vessels were only rarely banded with metal. 8 In fact, the narrow, “rolled” metal bands seen on black Ding bowls today, such as that on the bowl in the David Foundation Collection, likely were added much later either to set the bowl apart from the ordinary and thus mark it as special, or to conceal a bit of damage to the lip.

Northern Song black-glazed Ding wares may be left undecorated, as in the David Foundation bowl, or they may be embellished with so-called ‘partridge-feather’ mottles, or zheguban 鷓鴣斑, as in the Linyushanren and Harvard bowls. Such black glazes splashed with russet brown were produced by applying russet-brown slip to the surface of the glaze before fring. As with the black glaze itself, an oxide of iron was added to the slip to impart the russet color. The Ding kilns were the frst northern kilns to embellish their black-glazed wares with ‘partridge-feather’ mottles. Even so, Tao Gu’s mention in his tenth-century Qingyilu 陶穀清 異錄, or Records of Pure Marvels, of Jian tea bowls 建窯茶碗 with ‘partridgefeather’ markings suggests that such glazes might have originated at the Jian kilns in Fujian province 福建省建窯 and then spread to the north: “[Among] the tea bowls made in Min 閩 [Fujian] are ones decorated with ‘partridge-feather’ mottles; connoisseurs of tea prize them.” 9 We cannot know exactly what Tao Gu meant by “partridge-feather mottles”; however, if by that term he meant “black glazes dotted, fecked, or splashed with russet brown”, as the term traditionally has been used, then perhaps such glazes indeed originated at the Jian kilns and then spread to the north, where they were employed by the Ding kilns beginning late in the Northern Song period and subsequently, under the infuence of the Ding kilns, were adopted by many other northern kilns producing Cizhou-type 磁州窯系 wares during the Jin (1115–1234) and Yuan (1279–1368) dynasties.

As evinced by the Linyushanren and Harvard bowls, the distinctive, meticulously controlled, ‘partridge-feather’ glaze on Northern Song Ding ware features short, attenuated, vertically oriented, russet streaks atop a lustrous black glaze. Sparsely applied in a generally regular, recurring pattern around the interior of the bowls, the streaks at the top of the interior typically are thicker and bolder, those near the foor thinner and more delicate. In fact, the streaks appear to radiate outward from the vessel foor. A similar pattern generally occurs on the bowl’s exterior, albeit with fewer russet streaks. By contrast, the ‘partridge-feather’ glazes that appear on stoneware vessels produced at other northern kilns in the Jin and Yuan periods, typically at so-called Cizhou-type kilns, often feature russet dots, fecks, splashes, or dapples applied in controlled but somewhat random patterns, and their exteriors might be left undecorated, splashed with russet, or wholly covered with russet glaze.

The Chinese taste for dark-glazed wares developed alongside the taste for dark lacquer. Despite the predominance of cinnabar lacquer in the Ming and Qing dynasties, black and black-coffee brown were the preferred colors for lacquer in pre-Ming times. In the Tang and Song periods, ceramics often took aesthetic inspiration from lacquer ware, adopting the colors and forms of this expensive, luxury material. The increased demand for dark-glazed ceramics in the Song also refects changes in tea-drinking customs. The red tea consumed during the Tang, for example, was believed to look best in pale, bluish-green bowls, so bowls of celadon glazed Yue ware 越窯青磁釉 were preferred. 10 By contrast, the whipped, white tea that became popular in the Song was thought to look its best in black-glazed bowls, 11 so kilns in north and south alike increased their production of such wares.

During the Northern Song period, learned contestants participated in tea-preparation competitions, the quality of the tea judged on the basis of taste, fragrance, and appearance. In preparing tea at that time, whether for a contest or for pleasurable consumption, a measured amount of ground, powdered tea was spooned into a warmed tea bowl and a little hot water poured in from a ewer, after which the two ingredients were thoroughly combined to form a thick paste. When the paste was ready, more hot water was added and the mixture vigorously whipped to a froth with a bamboo whisk. A mid-tenth century text notes that in tea competitions “After mixing, the very best tea should appear pure white, and it should leave no residue on the bowl’s interior. … The frst tea to separate and leave traces of residue loses; the tea that stays well mixed the longest wins.” 12

The recorded comments of Northern Song connoisseurs indicate that tea bowls were designed as much to showcase the frothy, milk-white tea as to facilitate its preparation. Black glazes were desired because they showed the white tea to best advantage, while conical bowls were preferred because they most easily accommodated the bamboo whisk used for whipping the tea.

In summary, the Ding kilns were the frst to create lustrous black glazes, and they were the frst in the north to embellish their dark glazes with ‘partridge-feather’ mottles. Just as white Ding ware was the preferred ceramic ware at the Imperial Court during the eleventh and beginning of the twelfth century, so was black Ding ware prized there, particularly bowls appropriate for use in tea competitions, such as the magnifcent conical bowl from the Linyushanren Collection. As wares desired by the palace, Ding wares defned the style and set the aesthetic and technical standards of the day. Other kilns, including the Dangyangyu 當陽峪窯 and other Cizhou-type kilns 磁州窯系, of course followed suit, taking inspiration from Ding ware. So revered were Ding wares during the Northern Song period that collectors of all succeeding periods have continued to cherish them. In fact, already in 1388 the early Ming connoisseur and author Cao Zhao 曹昭 stated in his Gegu Yaolun 格古要論, or the Essential Criteria of Antiquities, “There is [also] brown Ding, whose color is purplish brown, and there is black Ding, whose color is lacquer black; [both] have pure white bodies; [their] prices exceed those of white Ding.” 13 That their prices surpassed that of white Ding ware already by 1388 well indicates the esteem in which collectors held dark-glazed Ding in the fourteenth century, a situation that obtains still today.

Formerly in the renowned collection of Eugene and Elva Bernat, then a gem of the Manno Museum, and now a jewel of the Linyushanren Collection, this ‘partridge-feather’ Ding bowl has an enviable provenance. And with its closest relatives in the Harvard, David Foundation, and National Palace Museum collections, this bowl keeps only the very best company. One from a tiny handful of extant ‘partridge-feather’ Ding bowls and the only one known still to be in private hands, this conical bowl indeed is an extraordinarily rare treasure.

1 For images of the Percival David Foundation bowl, see: Margaret Medley, Illustrated Catalogue of Ting and Allied Wares (London: University of London, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, School of Oriental and African Studies), 1980, p.16, no.31, pl. V; Rosemary Scott, Imperial Taste: Chinese Ceramics from the Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and London: Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art), 1989, p. 30, no. 8; Regina Krahl and Jessica Harrison-Hall,Chinese Ceramics: Highlights of the Sir Percival David Collection (London: British Museum Publications), 2009, p. 12, fg. 3.

2 For images of the two Harvard bowls, see: Robert D. Mowry, Hare’s Fur, Tortoiseshell, and Partridge Feathers: Chinese Brown- and Black-Glazed Ceramics, 400-1400 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums), 1996, pp. 115-116, no. 18 (1942.185.404), and pp. 111-112, no. 16 (1942.185.411).

3 The bowl is illustrated in National Palace Museum 國立故宮博物院, Art and Culture of the Song Dynasty: China at the Inception of the Second Millennium [Qian xi nian Songdai wenwu dazhan 千禧年宋代文物大展] (Taipei: National Palace Museum), 2000, p. 216, no. IV-34; it is also illustrated in Chiaki Ohshima 大島千秋, The Collection of Chinese Art: Special Exhibition ‘Run through 10 Years’ 中國美術蒐集: 千秋庭創立 10 週年記念展覽會 (Tokyo: Sen Shu Tey Gallery 千秋庭), 2006, p. 51, nos. 7, 8, 9).

4 See: Christie’s Hong Kong, 30 Years: The Sale, 30 May 2016, lot 3016.

5 See a white Ding conical bowl with molded decoration dated to the Jin dynasty and now in the collection of the British Museum, London (1947,0712.62) illustrated in Shelagh J. Vainker, Chinese Pottery and Porcelain: From Prehistory to the Present (London: British Museum Publications), 1991, p. 97, fg. 71. And see a white Ding conical bowl with molded decoration in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, illustrated in Tsai Meifen, Decorated Porcelains of Dingzhou: White Ding Wares from the Collection of the National Palace Museum (Taipei: National Palace Museum), 2014, nos. II-98, II-100-102, and II-121-124.

6 For images of the fngerprint impressions in the glaze on the bases of the Harvard bowls, see: Mowry, Hare’s Fur, Tortoiseshell, and Partridge Feathers, p. 111, Detail, no. 16, and p.116, Detail, no. 18.

7 See: Eugene Farrell, “Chinese Brown- and Black-Glazed Ceramics of the Song Dynasty: Technical Consideration” in Mowry, Hare’s Fur, Tortoiseshell, and Partridge Feathers, pp.59-77.

8 For information on the rare metal-banding of dark-glazed Ding wares, see: Mowry, Hare’s Fur, Tortoiseshell, and Partridge Feathers, pp. 107-108, no. 14.

9 Quoted in Feng Xianming 馮先銘, “Cong wenxian kan Tang Song yilai yincha fengshang ji taoci chaju de yanbian” [A Look at Tea-Drinking Customs and the Development of Ceramic Tea Utensils Since Tang and Song Times on the Basis of Literary References], Wenwu 文物, vol. 1 (1963), p. 10.

10 Lu Yü 陸羽, The Classic of Tea 茶經 (Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown, and Co.), 1974, trans. by Francis Ross Carpenter, pp. 90-93; also see Lu Yu, Chajing in Chashi chadian [Standard Works on Tea and Its History], ed. Zhu Xiaoming (Taipei, 1981), p. 22. Lu Yu (733-804) is believed to have written his Chajing, or Classic of Tea, between 760 and 762.

11 Cai Xiang 蔡襄, Chalu 茶錄 [A Record of Tea], in Chashi chadian [Standard Works on Tea and Its History], ed. Zhu Xiaoming (Taipei, 1981), p. 51. Cai Xiang (1012-1067) wrote his Chalu between 1049 and 1053.

12 Cai Xiang, 蔡襄, Chalu 茶錄, p. 89.

13 Quoted in Zhongguo taoci bianji weiyuanhui [Chinese Ceramics Editorial Committee], ed., Dingyao [Ding Ware], Zhongguo taoci [Chinese Ceramics] series, vol. 9 (Shanghai, 1983), n.p. (Appendix 1, Lidai wenxian zhulu); also see Sir Percival David, Chinese Connoisseurship: The Ko Ku Yao Lun (London, 1971), trans. and ed. Sir Percival David, with a facsimile of the 1388 text, p. 141 (Chinese text, p. 306, nos. 39a-b).

Christie's. The Classic Age of Chinese Ceramics - The Linyushanren Collection, Part III, 22 March 2018, New York

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240410%2Fob_77912a_2024-nyr-22642-0912-000-a-superb-and-v.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F61%2F20%2F119589%2F121189812.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F25%2F68%2F119589%2F121184270_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F35%2F76%2F119589%2F121184076_o.png)