Extraordinary rediscovery: Lost treasure of Imperial China found in an Attic in France

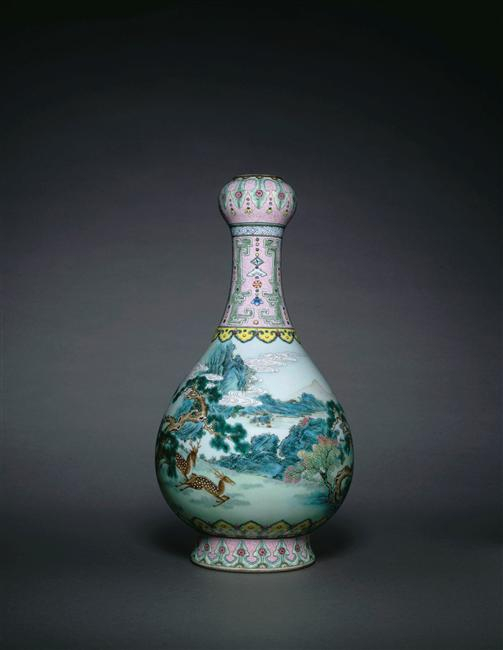

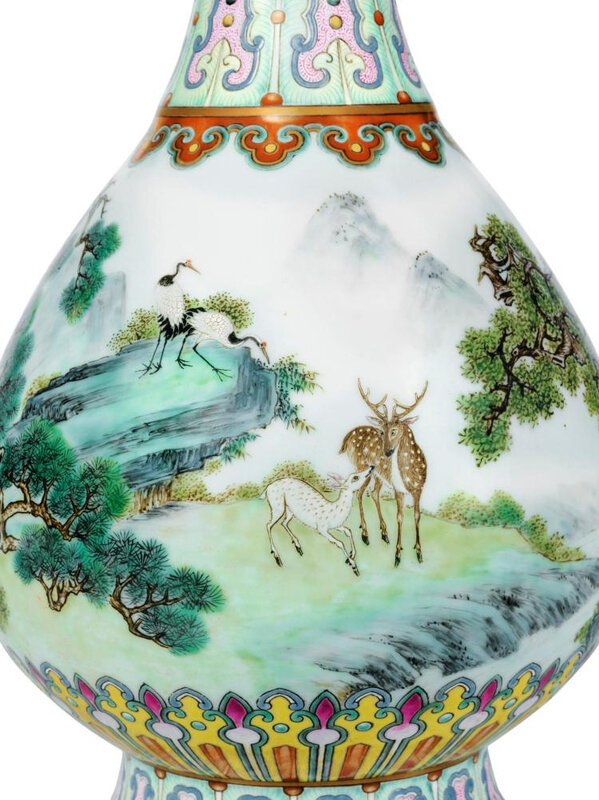

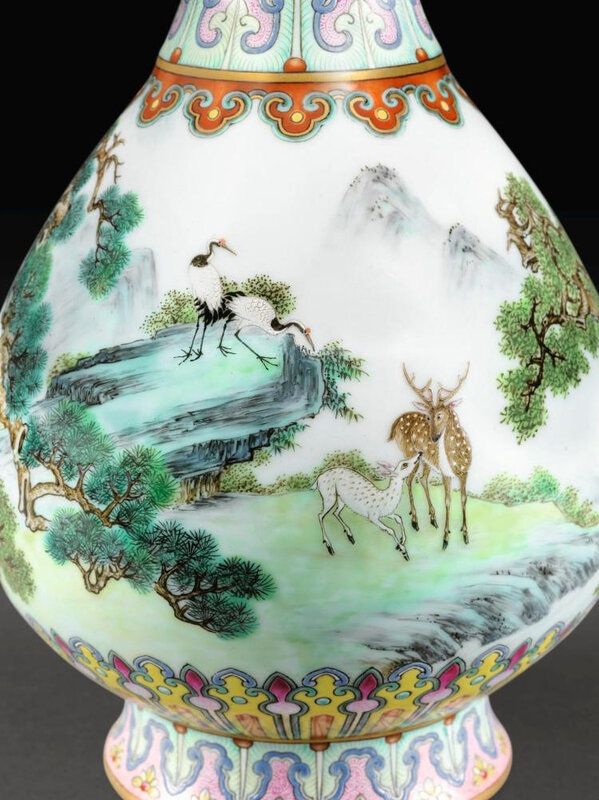

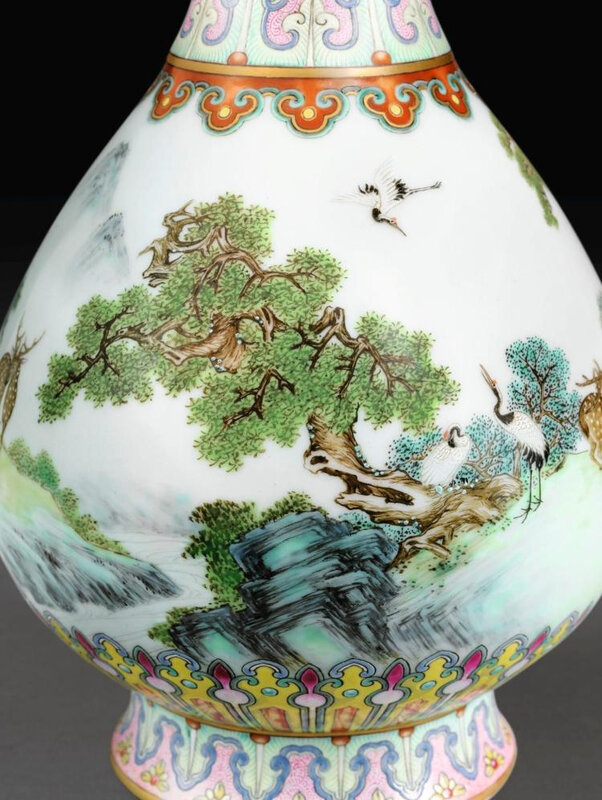

A unique Imperial 18th century ‘Yangcai’ Famille-Rose porcelain vase, Qianlong mark and period (1736-1795). Estimate £430,000 – 610,000 (€500,000 – 700,000 / US$ 600,000 – 850,000 / HK$4.8-6.7 million). Lot sold 16,182,800 EUR. Courtesy Sotheby's.

PARIS – Today in Paris, Sotheby’s unveils an extraordinary recently-discovered treasure of Imperial China: a unique Imperial 18th century ‘Yangcai’ Famille-Rose porcelain vase, bearing a mark from the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1795). Discovered by chance in the attic of French family home, this magnificent vase was brought into Sotheby’s Paris by its unsuspecting owners in a shoe box. When Sotheby’s specialist Olivier Valmier, opened the box to examine the vase, he was immediately struck by its quality. Further research revealed the vase to be a unique example produced by the finest craftsmen of the time for the Qianlong Emperor. Of extraordinary importance and rarity, the vase will now be offered for sale at Sotheby’s in Paris on 12 June, with an estimate of £430,000 – 610,000 (€500,000 – 700,000 / US$ 600,000 – 850,000 / HK$4.8-6.7 million).

Left to the grandparents of the present owners by an uncle, the vase is listed among the contents of the latter’s Paris apartment after his death in 1947. It is recorded alongside several other Chinese and Japanese objects including other Chinese porcelains, two dragon robes, a yellow silk textile, and an unusual bronze mirror contained in a carved lacquer box. This mirror will be offered in the Sotheby’s sale of Asian Art in Paris immediately after the sale of the vase.

While the exact provenance of the vase and the other Chinese and Japanese pieces before 1947 cannot be traced, the receipt of a Satsuma censer acquired as a wedding gift in the 1867 Universal Exhibition in Paris by an ancestor of the family suggests an active interest in Asian art at a very early date. Similarly, this vase may well have been acquired in Paris in the late 19th century when the arrival of Asian works of art initiated a fashion for Japanese and Chinese art. Interestingly, the only other vase of this shape and similar design, now in the collection of the Musée Guimet, Paris, was acquired by Ernest Grandidier (1833-1912) about the same time, around 1890 from Philippe Sichel, an Asian art dealer in Paris active in the late 19th century, and an early advocate of Japanese art in France.

The vase is of exceptional rarity: the only known example of its kind, it was produced by the Jingdezhen workshops for the magnificent courts of the Qianlong Emperor (1735-1796). Famille Rose porcelains of the period (or ‘yangcai’ porcelains, as they are known) are extremely rare on the market, with most examples currently housed in the National Palace Museum in Taipei and other museums around the world. On the rare occasions when pieces of this kind do come to auction they are the subject of fierce competition: earlier this year in Hong Kong a Famille-Rose porcelain bowl sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong for HK$239 million (£21.7 million; US$30.4 million) in April this year.

These so-called yangcai porcelain commissions were the very epitome of the ware produced by the Jingdezhen imperial kilns. They were made as one-of-a-kind items, sometimes in pairs, but never in large quantities. This technique combined a new colour palette with Western-style compositions. Beyond their superior quality, yangcai enamels were intended to create the most opulent and luxurious effect possible.

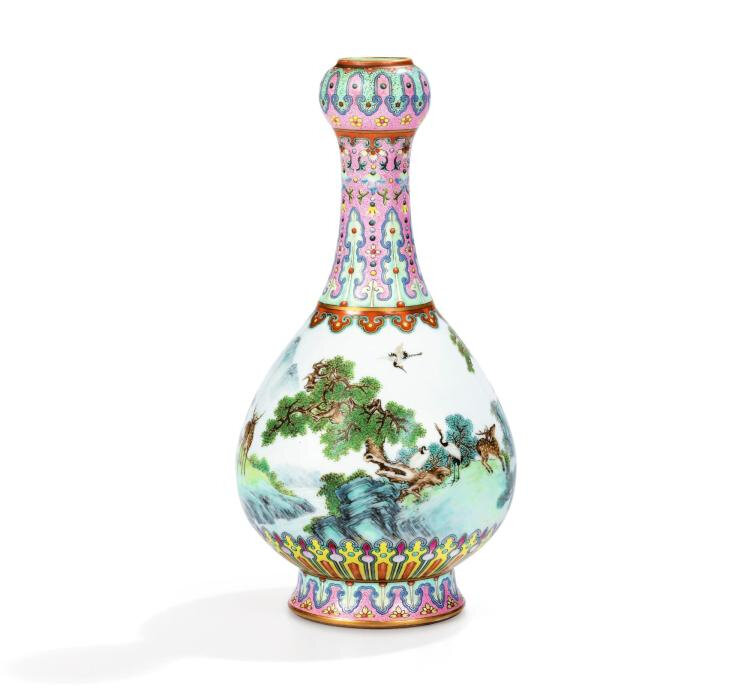

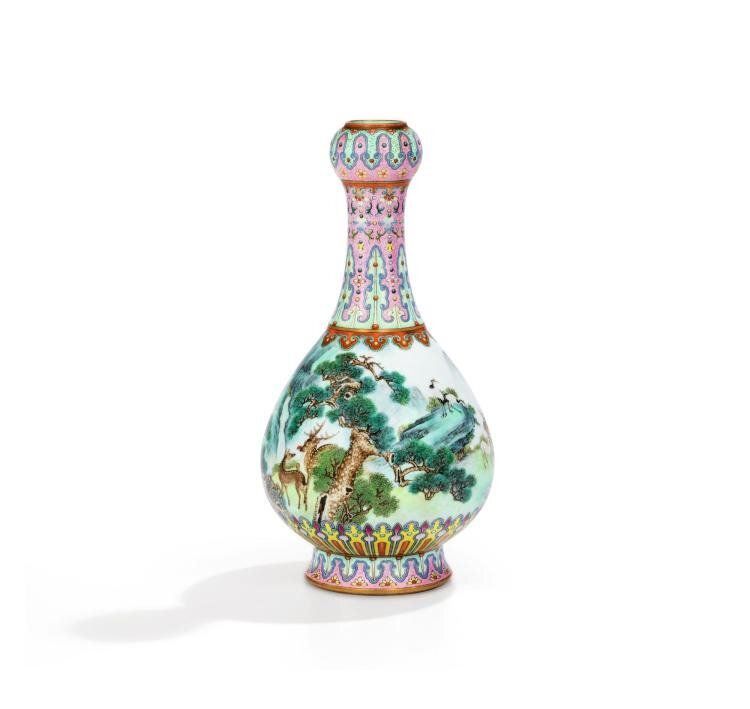

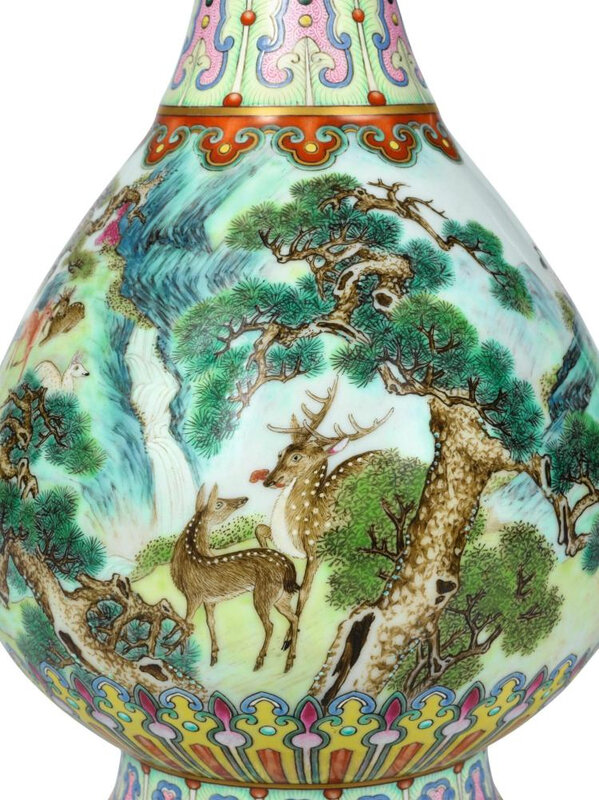

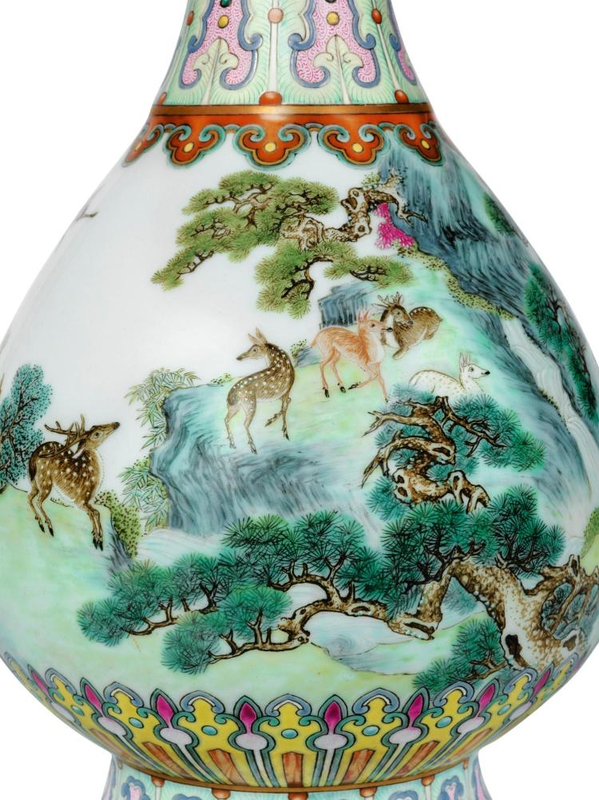

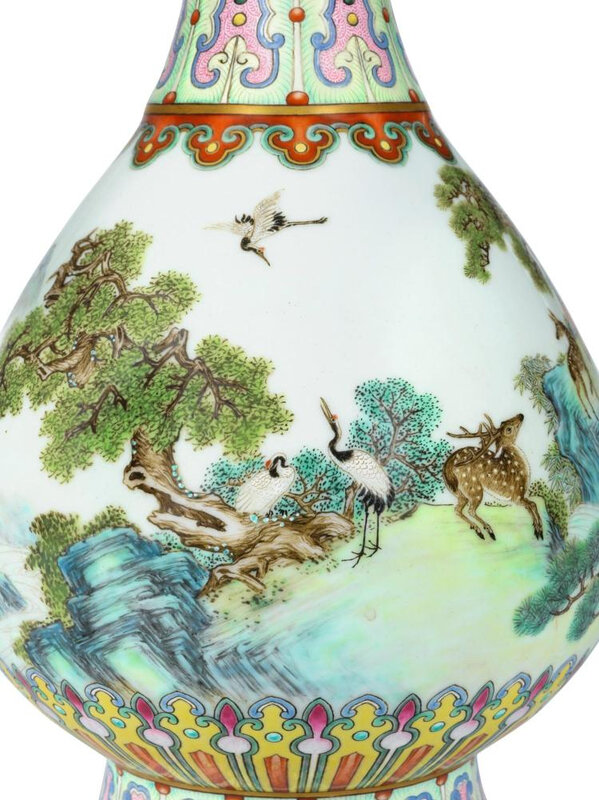

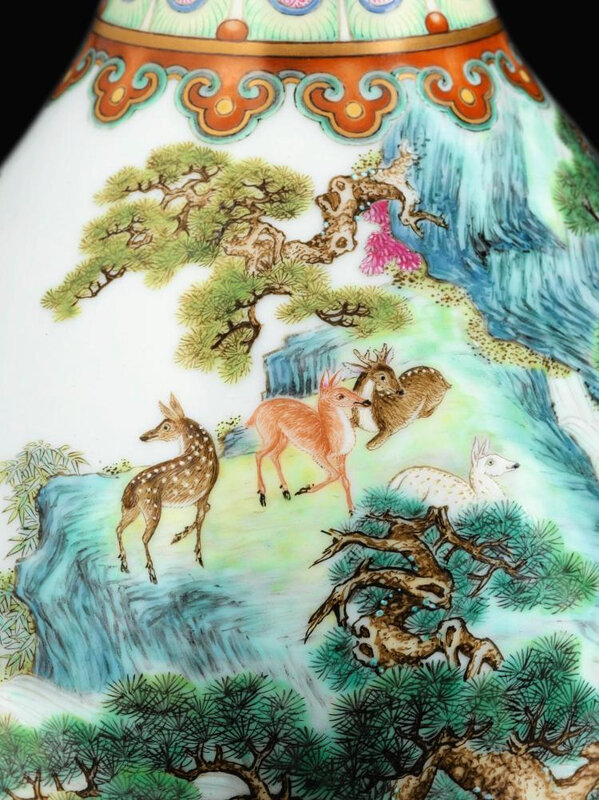

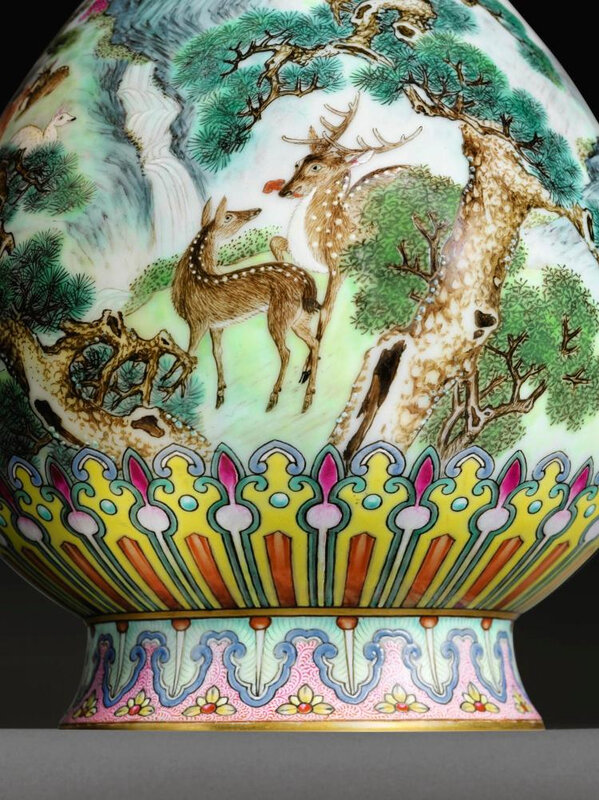

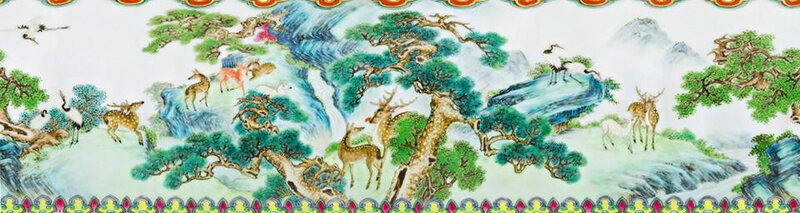

The vase, to be sold at Sotheby’s in Paris, has a body encircled by a magnificent landscape with deer, cranes and pine trees, all auspicious symbols of health and longevity: a genuine painting on porcelain showing nine fallow deer and five cranes in a rocky landscape with a tumbling waterfall, surrounded by gnarled pines and mist-covered peaks expressing all the artist's dazzling talent. Only one other similar vase, although with slightly different subject matter and decorative borders, now in the Guimet museum in Paris, is known. This naturalistic garden most probably illustrates one of the Imperial parks designed for the Emperor's delight. The scene may seem ordinary, but is in fact highly symbolic. The fallow deer, synonymous with happiness and prosperity, is often shown as the mount of the god of longevity. Cranes, personifying old age, also carried immortals through the air. Lastly, immortality is represented by lingzhi, mushrooms growing on the islands where the gods dwelt.

The Imperial inventories drawn up in the 18th century mention pairs of vases with this design twice: one pair commissioned in 1765; the other ordered as a birthday gift in 1769.

Henry Howard-Sneyd, Sotheby's Chairman of Asian Art, Europe and Americas, said: “Chinese art has been admired and collected across Europe for centuries, but the importance of certain pieces is occasionally lost over time. Given the huge appetite for Chinese art among today’s collectors, now is the moment to scour your homes and attics, and to come to us with anything you might find!”

Magnifique et important vase impérial de la famille rose, marque et époque Qianlong (1736-1795); 28 cm, 11 in. Estimation €500,000 – 700,000 ( £430,000 – 610,000 / US$ 600,000 – 850,000 / HK$4.8-6.7 million). Lot vendu 16,182,800 EUR. Courtesy Sotheby's.

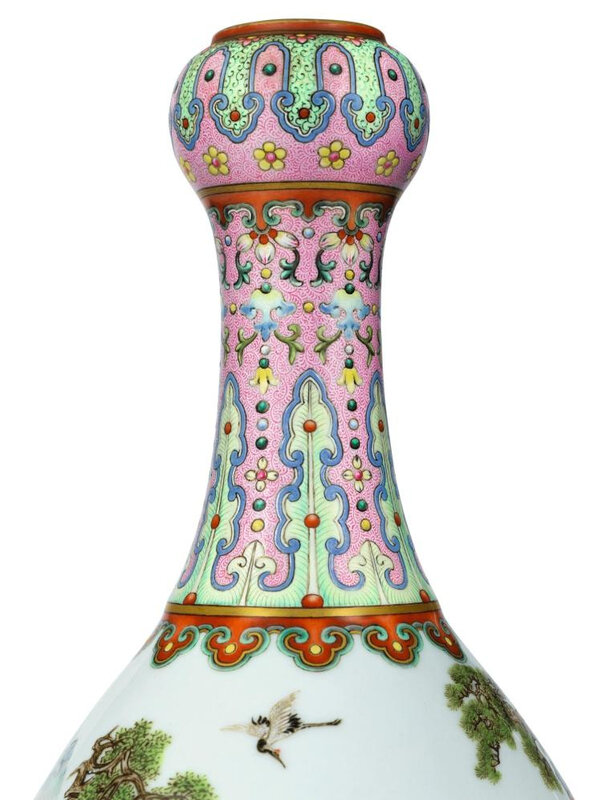

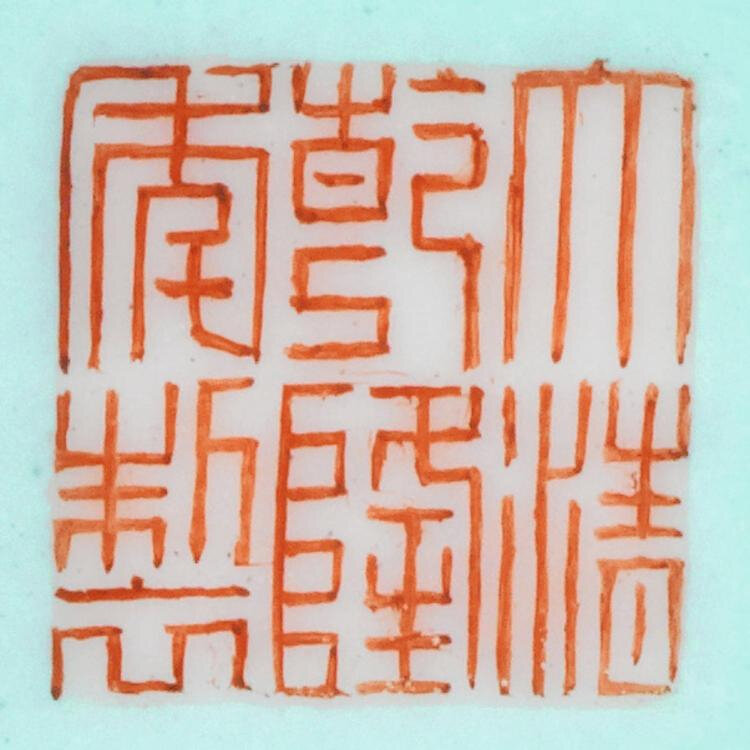

la panse piriforme reposant sur un pied évasé et se prolongeant gracieusement en un haut col étroit se terminant en un bulbe surmonté d’un court bord droit, le panse finement peinte d'une scène continue de daims et de grues s'égayant dans un paysage rocailleux à la végétation foisonnante, au-dessus d'une bande de palmes vivement émaillées de jaune aux détails multicolores, le col ceint de palmes vert pâle délimitées par un cerne bleu et rehaussées de perles rouge-de-fer, bordé en dessous d'un anneau doré et de têtes de ruyi en dégradés de rouge-de-fer et rehaussé d’or, le col délicatement peint de deux registres de fleurs multicolores stylisées dans leurs rinceaux feuillagés suspendant de petites perles colorées, le tout contre un fond émaillé rose finement détaillée de plumettes rose foncé, le bulbe rythmé de fleurettes sous une chute de lames se terminant en têtes de ruyi vert pâle détaillées d'enroulements vert foncé, le col ceint d’une bande de petites têtes de ruyi en rouge-de-fer séparé du bulbe par un filet doré, le pied peint de palmettes descendantes en vert pâle alternant avec des fleurettes jaunes, le tout sur un fond rose finement détaillé de plumettes rose foncé, l’intérieur et la base émaillés turquoise, la base inscrite d’une marque de règne à six caractères sigillaires en rouge-de-fer dans un carré blanc.

… Where Cranes and Deer Become Immortals Who Never Age …

Regina Krahl

Throughout his life, the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1795) would have been surrounded by auspiciousness. Architectural design, interior decoration, paintings, dress, practical utensils, all were brimming with positive symbolism that was meant both to reflect and to support the Emperor’s virtuous and benevolent governance. And this was not restricted to the inanimate world. Imperial gardens were turned into veritable tableaux vivants, where auspicious animals, birds and plants were assembled to present the Emperor with an idealized view of nature, full of good omens.

This magnificent, unique vase abounds with positive symbolism; but what at first glance looks like a purely imaginary, paradisiacal landscape composed of auspicious design elements, is probably a fairly naturalistic rendering of one of the Qianlong Emperor’s imperial pleasure parks. As early as the Western Zhou period (1046-771 BC), deer and cranes were kept in palace gardens for delectation; by the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) the sophistication of such imperial gardens was most likely hard to surpass. In the ‘Pictures of Pleasurable Activities’ (xing le tu), which depict Qing emperors at leisure, we frequently see both the Qianlong and his father, the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1723-1735) seated at ease in a garden pavilion among lush vegetation watching deer or cranes (e.g. The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Paintings by the Court Artists of the Qing Court, Shanghai, 1999, pls 10, 59).

To escape the summer heat in the capital, the Qianlong Emperor used to move to one of his summer residences around Beijing, such as the famous Imperial Hunting Preserve Mulan near Chengde in Rehe (Jehol), northeast of Beijing, a temporary summer capital, where he continued to conduct state affairs. The British envoy of King George III (r. 1760-1801), Lord Macartney (1737-1806), whom he received there, was duly impressed by the scenic beauty of the location with its wooded hills with ancient trees, dramatic rocks and a rich stock of stags and deer.

In a poem headed ‘Returning by Imperial Carriage from Mulan to the Palace, on Reaching Avoiding Summer Heat Mountain Villa I Respectfully Pay my Respects and Wish the Empress Dowager Well’, the Qianlong Emperor writes (translated by Richard Lynn):

Though written letters may say all, convenient for everyday life,

When her year has nearly come full circle I always rush to her side,

Where, paying homage, I mull over my shortcomings for more than twenty days,

And for her enjoyment wish that she be blessed with a myriad more years.

These pavilions and terraces, always a realm for cultivating longevity,

Are where cranes and deer both become immortals who never age.

Retired to the Rocky Crag Studio, I sincerely offer my congratulations and comfort,

Where window coverings are painted with the reds and greens of beautiful peaks.

Another of these summer palaces is referred to in his poem ‘Inspired by a Summer Day at the Garden of Quietude and Repose (Jingyiyuan) in the Fragrant Hills’, west of Beijing (also translated by Richard Lynn):

At a country retreat not very far, to and from it an easy trip,

Where orchid and capsicum spread and climb I open its cloudy gate.

Here viewing mountains I can better endure a half day’s fast,

Or escaping summer heat fleetingly chance the leisure of an entire day.

Cranes lead their fledglings hither to preen their young feathers,

And deer after molting’s finished grow new dappled coats.

So why must one’s study be a place where only stitched volumes are opened?

For behold, Fu’s mother earth trigrams [the broken and unbroken lines attributed to the mythological sage Fu] are recorded all over this place!

The most renowned painter at the Emperor’s court, the Italian Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), painted these cranes with their young, and was also commissioned for the sixtieth birthday of the Empress Dowager to record an auspicious white ‘long life’ deer that had been offered that year by Mongol tribes on the occasion of the autumn hunt, a painting that the Emperor himself inscribed to the effect (Wang Yaoting, Lang Shining yu Qing gong xiyang feng/New Visions at the Ch’ing Court. Giuseppe Castiglione and Western-Style Trends, catalogue of an exhibition at the National Palace Museum, Taipei, 2007, pls 17, 22).

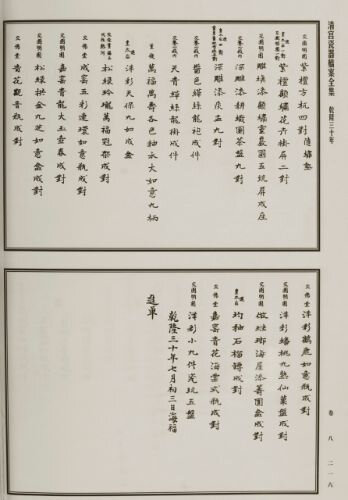

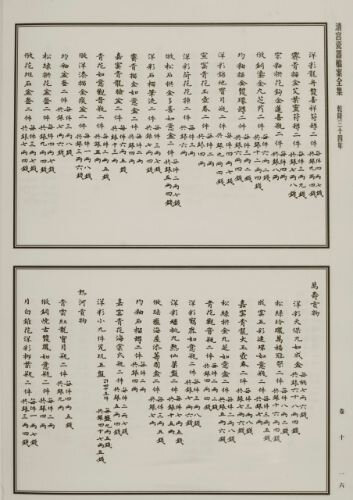

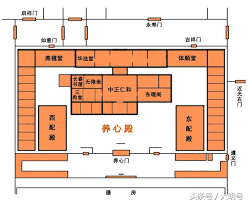

Idyllic landscapes with deer and cranes such as depicted on this vase are, however, exceedingly rare on Qing imperial porcelain and did not form part of the imperial kilns’ regular production lines. In the Qing gong ciqi dang’an quanji[Complete records on porcelain from the Qing court] ‘Yangcai ruyi vases with cranes and deer’ are recorded only twice. In the thirtieth year of Qianlong (1765) a pair of such vases is recorded by the Eunuch Haifu to have been delivered to one of the Buddha Halls (fotang) (Fig.2) ; and in the thirty-forth year of Qianlong (1769) two such vases are recorded as having been ordered as a birthday tribute, each costing three liang (taels) and eight qian, together seven liang and six qian (Fig. 3 ). ‘Buddha Halls’ were places of private worship, housing altars for domestic ancestral rites and were part of the Emperor’s private residences. Two Buddha Halls, one east, one west, were flanking the courtyard of the Yangxindian inside the Forbidden City, next to the Sanxitang, the Hall of Three Rarities, and equally formed part of the Emperor’s residence within the Yuanmingyuan (Fig. 4).

Fig.2. Qing gong ciqi dang’an quanji, juan 8 : 216.

Fig. 3. Qing gong ciqi dang’an quanji, juan 10 : 16.

Fig. 4. Plan of the Yangxindian.

Such special orders of yangcai were sent to the Jingdezhen imperial workshops and represented the cream of the ateliers’ production. Yangcai was the imperial Jingdezhen workshop’s answer to the challenge represented by falangcai, porcelains made in Jingdezhen but exquisitely painted in imperial workshops in Beijing. Both terms mean ‘foreign colours’ and acknowledge technical exchanges with the West, both making use of the new palette, that had been enriched by enamels introduced to the Chinese workshops by European Jesuit craftsmen. Yangcai in addition often incorporates Western-style shading in its floral compositions. In both cases, pieces tended to be produced either as unique items or in pairs, but not in greater numbers, as distinct from Jingdezhen’s regular supply for the imperial court, which was executed in much larger series.

The enchanting scene on the present vase shows nine deer, some grouped as pairs, with males and females glancing at each other, one holding a lingzhi in its mouth, the females with differently coloured coats, and five cranes in flight or on the ground, in a landscape with dramatic rock formations, ancient gnarled pine trees and misty mountain peaks in the distance. Deer, lu, homophone with a word signifying happiness and prosperity, are often depicted as a mount for Shou Xing, the God of Longevity. Cranes, he, symbolizing old age already on account of their white feathers, are similarly represented carrying immortals through the air. The evergreen pine tree symbolizes long life, the rare lingzhi, a fungus believed to grow on the island abodes of the Immortals, immortality. The ruyi motif, itself derived from the shape of the ling fungus, is best known from ruyi sceptres that are shaped in this way, which were bestowed as wish-fulfilling talismans.

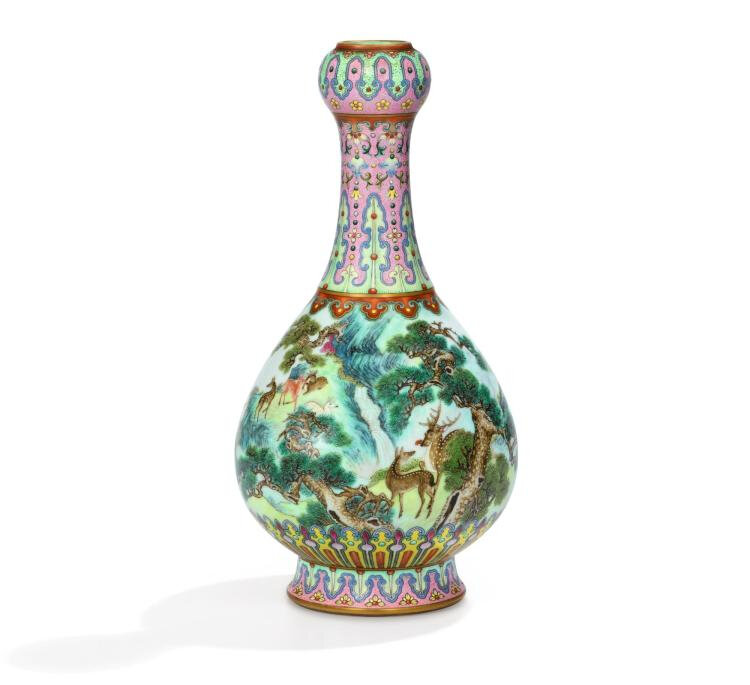

Only one other vase of similar design appears to be recorded, also preserved in France, from the important collection of Ernest Grandidier (1833-1912), today in the Musée Guimet, Paris, illustrated in Xavier Besse, La Chine des porcelaines, Paris, 2004, pl. 56 (fig. 1). Although very different in execution and almost certainly painted by different hands, the two vases are closely comparable in their basic form and design, and the painting manner of their respective nature scenes seems equally indebted to the style of Giuseppe Castiglione’ paintings on silk.

A rare pink-ground Yangcai ‘auspicious deer’ garlic-mouth vase, Qianlong mark and period, Collection Ernest Grandidier, G 620, Musee Guimet © RMN-Grand Palais (MNAAG, Paris) / Richard Lambert.

What makes yangcai distinctive, besides its superior quality, was an innovation of the Jingdezhen workshops under the patronage of the Qianlong Emperor: the highly complex, labour-intensive, multi-coloured brocade-like fields and borders of formal floral-and-pearl designs on a sgraffiato or mock-sgraffiato ground that were clearly devised to create an effect as opulent and luxurious as possible. The sgraffiato scrollwork, usually incised with a needle into the coloured enamel, is on the present piece and on the Grandidier vase replaced by delicately painted lines, a process perhaps even more demanding than the fine engraving itself. The pearl motifs among the floral designs, shaded to appear three-dimensional, give the whole design a rich, bejewelled aspect, and the ruyi and lanceolate borders with their highly sophisticated shading in subtle enamel tones lend the surface a rare vibrancy.

Yangcai porcelains are extremely rare outside the National Palace Museum, Taipei, whose rich collection has been the subject of a study by Liao Pao Show (Liao Baoxiu), Huali cai ci: Qianlong yangcai/Stunning Decorative Porcelains from the Ch’ien-lung Reign, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 2008. It shows the wide variety of vases decorated in a similar combination of nature scenes and ornamental brocade-like patterns on coloured grounds. Although many vases in Taipei are stylistically comparable and display very similar supporting designs, the publication documents how rarely we encounter yangcai vases with complete ‘paintings’ in handscroll format, like the auspicious landscapes on the present vase and that from the Grandidier collection. Liao illustrates one vase of similar shape, but of much smaller size, decorated with floral panels on a gold-decorated ground, with similar pale green ruyi lappets filled with scrollwork, ibid., pl. 38, identified as an order of 1742, and indeed, orders for these yangcai vases generally seem to date from a few years in the early 1740s. The successful completion of such tours de force can undoubtedly be ascribed to the ambition and expertise of Tang Ying (1682-1756), the unsurpassed kiln supervisor at Jingdezhen, who managed to push the porcelain industry at Jingdezhen to its very limits.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F84%2F15%2F119589%2F129856641_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F80%2F06%2F119589%2F129835168_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F77%2F85%2F119589%2F122169587_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F74%2F57%2F119589%2F122168457_o.jpg)