The J. Paul Getty Museum presents 'Blurring the Line: Manuscripts in the Age of Print'

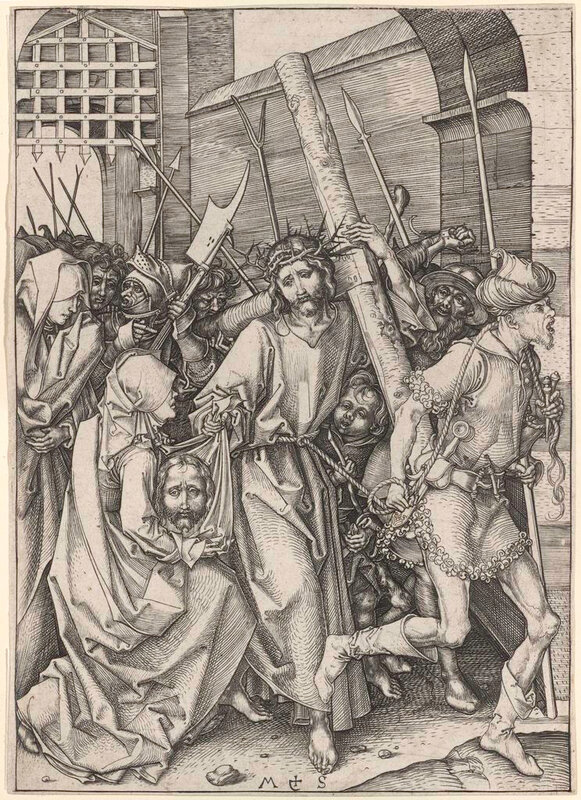

Left: The Way to Calvary and Saint Veronica with the Sudarium (detail), from the Spinola Hours, Bruges, about 1510-20, Master of James IV of Scotland; tempera colors, gold, and ink on parchment. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Right: Christ Carrying the Cross (detail), Germany, about 1475-80, Martin Schongauer, engraving on paper. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Mrs. Edgar Sinton, 1981.1.106.

LOS ANGELES, CA.- Throughout the Middle Ages (about 500-1500), texts and images were disseminated primarily through handwritten and hand-drawn materials. In the 15th century, with the invention of new printing technologies, a revolution swept through Europe giving rise to a rich cross-fertilization between mechanical innovation and painterly tradition.

Including both printed and illuminated masterpieces, Blurring the Line: Manuscripts in the Age of Print (on view from August 6 through October 27, 2019 at the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center) challenges the assumption that printed media immediately replaced the production of handmade books, revealing instead a convergence of technology and artistry during the Renaissance.

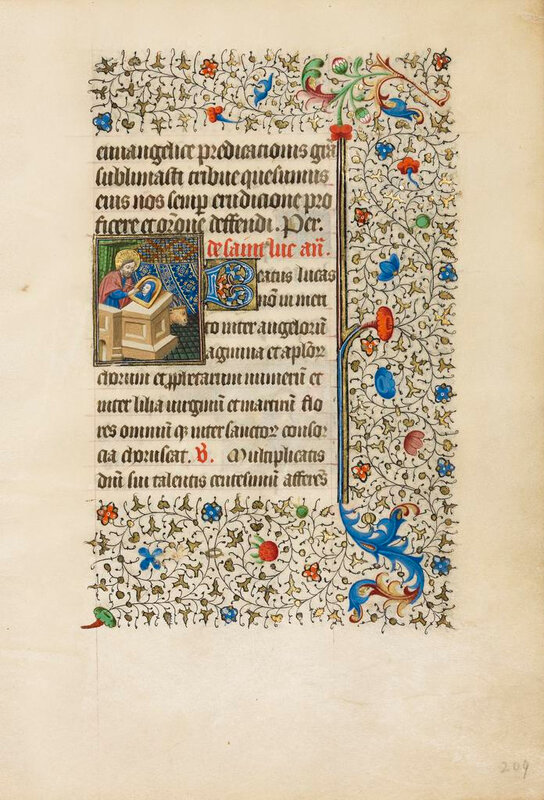

Saint Luke Painting an Image of the Virgin, from a book of hours (text in Latin), France, about 1440–50, Workshop of the Bedford Master, tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, and ink on parchment. Leaf: 23.5 × 16.4 cm (9 1/4 × 6 7/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 6, fol. 209.

“An innovation of the medieval world, print was a medium that grew and changed in response to those who created and consumed it,” says Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “This is especially evident in the medieval and Renaissance periods, but the dynamic interaction between technology and artistic change is timeless—as we see in the transition from painting to photography, film to digital, and paper books to eReaders.”

In a world before print, text and images were manually copied in books and on panels by skilled artists, inevitably introducing variations. Exact replication was associated with divine intervention, perceived as a miraculous transfer of likeness through a saintly intermediary. The printed image opened new and more straightforward possibilities for precise reproduction while drawing heavily on medieval conventions of composition, such as iconography, two-dimensionality, added color, and portable size.

Christ Carrying the Cross, Germany, about 1475–80, Martin Schongauer, engraving on paper. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Mrs. Edgar Sinton, 1981.1.106. © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Just as many different technologies overlap in today’s world, printing did not immediately eclipse all other forms of book art in the 15th century; it was a much more complex relationship. Printers and illuminators readily shared ideas, frequently borrowing compositions from one another. Printers recognized the importance of enhancing their new products by imitating the craftsmanship in illuminated manuscripts, a form associated with wealth and prestige. Nevertheless, the illuminator’s skill continued to be valued by those with the means to commission luxury handmade books. As a result of the competition and coexistence of these two media, the 15th century saw an expansion of pictorial literacy and a new era of affordable images at the same time the art of illumination was pushed to new levels of creative achievement.

The Way to Calvary and Saint Veronica with the Sudarium, from the Spinola Hours, Bruges, about 1510-20, Master of James IV of Scotland; tempera colors, gold, and ink on parchment. Leaf: 13.5 × 10.5 cm (5 5/16 × 4 1/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig IX 18, fol. 8v.

The exhibition includes a selection of handmade books produced in the centuries after the introduction of the printing press. Though production of illuminated manuscripts slowed, handmade books were valued for their specialized craftsmanship and the prestige of the tradition they represented. They were treasured in religious, courtly, governmental, and other exclusive circles. Such personalized, made-to-order books attested to the wealth, high social status, and good taste of their patrons and owners. While print increasingly became the dominant mode of book production, illuminated manuscripts were preserved and reinvented in the post-medieval era.

The Visitation, Italy, 1505–15, Marcantonio Raimondi after Albrecht Dürer, engraving on paper. Unframed: 30.5 × 21.6 cm (12 × 8 1/2 in.) Framed: 60 × 49.8 × 3.2 cm (23 5/8 × 19 5/8 × 1 1/4 in.). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Helen Lundenberg Feitelson in memory of Lorser Feitelson, M.80.33.74. Image: www.lacma.org.

According to Larisa Grollemond, assistant curator in the department of Manuscripts and curator of the exhibition, “The late 15th century is a fascinating moment in terms of artists experimenting with manuscript illumination and print, often fusing the two media in the same book. We tend to think that when print was introduced in Western Europe, illumination became a thing of the past. There’s actually a really complex artistic negotiation between these two forms that I think is similar to what’s happening today between digital and print media. I hope that visitors will be able to find some (perhaps surprising) parallels between the 15th and 21st centuries!”

Blurring the Line: Manuscripts in the Age of Print is curated by Larisa Grollemond, assistant curator in the Manuscripts Department, and Alexandra Kaczenski, former graduate intern in the Manuscripts Department, and will be on view August 6 through October 27, 2019 at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

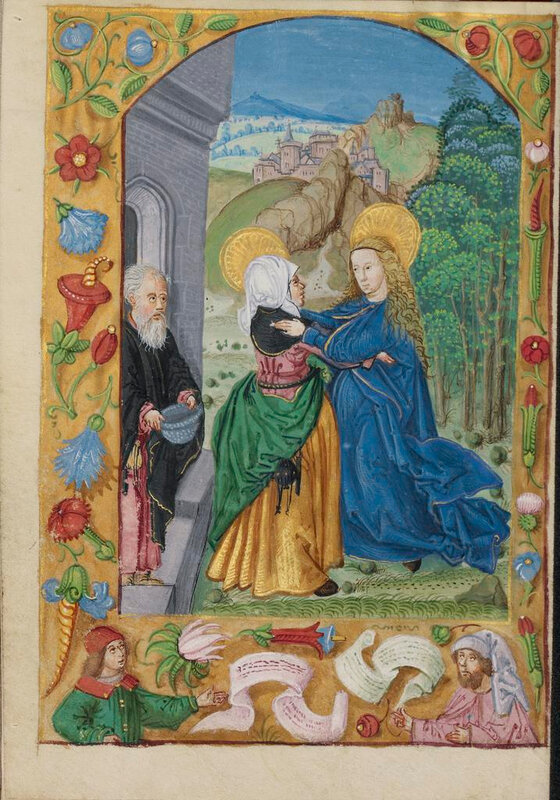

The Visitation, from a book of hours (text in Latin), France, early 16th century, artist unknown, tempera colors on parchment. Leaf: 13.5 × 10.5 cm (5 5/16 × 4 1/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museumm, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig IX 16, fol. 165v.

The Sudarium, Displayed by Two Angels, 1513, Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471 - 1528). Unframed: 10.2 × 14.3 cm (4 × 5 5/8 in.). Framed: 39.7 × 52.4 × 3.2 cm (15 5/8 × 20 5/8 × 1 1/4 in.). L.2018.147. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Fund. image: www.lacma.org.

Crucifixion, from Missal of Bishop Antonio Scarampi (text in Latin), Italy, 1567, Fra Vincentius a Fundis, tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment. Leaf: 41 × 27 cm (16 1/8 × 10 5/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig V 7, fol. 11v.

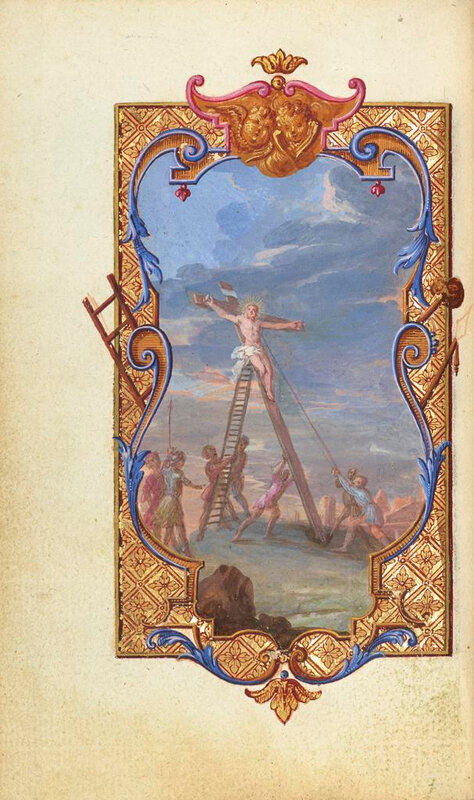

The Raising of the Cross, about 1720 – 1730, Jean Pierre Rousselet (French, active about 1677 - 1736). Tempera and gold leaf on paper bound between pasteboard covered outside in original dark blue morocco, and inside in red morocco in fanfare style. Leaf: 11.9 × 7.1 cm (4 11/16 × 2 13/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig V 8, fol. 19v.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F46%2F19%2F119589%2F111230959_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F54%2F20%2F119589%2F93291728_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F67%2F63%2F119589%2F71503890_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240406%2Fob_91443a_gg-6944-202104-nr.jpg)