Art to wear: Christie's to offer jewellery by artists selected by Didier Ltd

.jpg)

Harry Bertoia (1915-1978), A unique and substantial gong pendant, 1960s. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

LONDON.- Christie’s presents an online selling exhibition of jewellery, miniature artistic expressions by leading 20th century artists. Art to Wear is a partnership with Didier Ltd, a London-based gallery that specialises in twentieth-century artist-designed jewellery. Producing pieces to adorn the body of the wearer, artists including Salvador Dalí, Claude Lalanne, Georges Braque, and Alexander Calder found the medium provided a means to free their imagination, crafting portable artworks that are as functional as they are expressive. The exhibition will explore the creative process with photographs, sketches and texts giving viewers insight into this unique aspect of the artist’s oeuvre. The 17 objects presented transcend eras and channel art, innovation and technique to create luxurious and bespoke expressions suitable for daily wear. The exhibition will underline the cultural and art historical contexts within which these objects were brought into existence. Works from the exhibition are available for immediate purchase with a price range of £20,000-150,000.

Arman’s playful necklace encapsulates the sense of abandon that artists embraced when crafting wearable sculptures. The 19 small gold paint tubes form a classic V-shape around the neck. Harry Bertoia’s hand-hammered gong pendant echoes the principal exploration of sound that his work is renowned for, whilst simultaneously celebrating a form that appears ancient, and timeless. Bertoia first started making and indeed teaching jewellery while he was head of the metalwork department at the Cranbrook Academy of Art during the Second World War. As metal supplies dwindled during the war, Bertoia started to work out his ideas on a smaller scale, his jewels becoming maquettes with which to organise and develop his ideas. Claude Lalanne’s work has a sinuous, organic form, incorporating flora and fauna in a manner that is reminiscent of Art Nouveau, with a delicate infusion of surrealism and fantasy. The exhibition will include an 18ct gold front fastening necklace that is formed from articulated hydrangea flower petals arranged in a graduated manner.

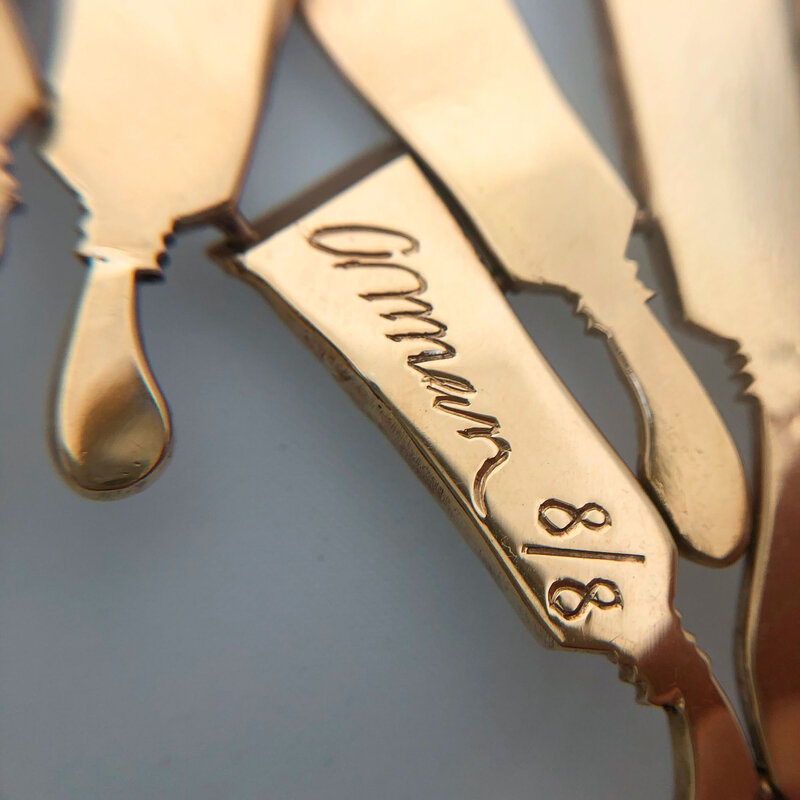

Arman (1928-2005), A necklace, 1991. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

18ct gold, clasp with double safety clip, cast as cascading paint tubes suspended from triple-link chain, produced by Argeco, Nice, number 8 from the edition of 8 plus 4 artist's proofs, 38 cm. long (14.17/16 in.), pendant 5 x 10.5 cm. (2 x 4 1/8 in.), stamped with signature on the reverse Arman, 8/8 and with Nice hallmark, the clasp further stamped with Nice eagle's head hallmark.

Literature: J.L. Billant, Rare Collection of Artist’s Jewels by Argeco, Arman 1928-2005, Nice, another example illustrated pp. 37, 43, 46.

Note: This necklace design is recorded in the Arman Studio Archives, New York, under number APA 7041.91,002.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Arman (1928-2005), A cased set of eight pendants, 1995-2000. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

18ct gold, three with enamel decorations, the square pendant with acrylic inset, together with original case marked with artist’s facsimile signature, produced by Pierre Hugo for Galerie Stéphane Klein, each pendant from their respective limited editions.

The set comprising:

A ‘Pinceaux’ 18ct gold pendant with two suspension loops, decorated with 17 wet paint brushes and their brush strokes, number 19 from the edition of 25, inscribed 3012 1809/A, 19/25, signed Arman in the cast and stamped with Pierre Hugo's Société les Cyprès d'or and French eagle's head hallmarks, 6.1 high x 5.7 cm. wide (2 3/8 x 2 ¼ in.)

A ‘Tubes’ 18ct gold pendant with two suspension loops, squashed screw-topped paint-tubes arranged in two rows of eleven, number 19 from the edition of 25, inscribed 3013, 1810/A, 19/25, signed Arman in the cast and stamped with Pierre Hugo's Société les Cyprès d'or and French eagle's head hallmarks, 7.6 high x 5.5 cm. wide (3 x 2 3/16 in.)

A ‘Long Term Parking’ 18ct gold pendant, a miniature of the artist’s sculpture depicting nine rows of cars set in concrete, retractable suspension loop, number 19 from the edition of 50, inscribed 2958 1812/A, 19/50, signed Arman in the cast and stamped with Pierre Hugo's Société les Cyprès d'or and French eagle's head hallmarks, 5.7 x 1.8 cm. square (2 ¼ x 0.9/24 in.)

A ‘Violons’ 18ct gold pendant with three sliced violins joined by violin bows, arranged in a triangle, with a single loop, number 19 from the edition of 25, inscribed 3015 1811, 19/25, signed Arman in the cast and stamped with Pierre Hugo's Société les Cyprès d'or and French eagle's head hallmarks, 5.6 cm. square (2.6/16 in. )

A ‘Dollar’ 18ct gold pendant with a 1895 Double Eagle Liberty Head US 20$ coin sliced into five parts and set in acrylic within a gold frame, number 19 from the edition of 50, inscribed 19/50, signed Arman in the cast and stamped with Pierre Hugo's Société les Cyprès d'or and French eagle's head hallmarks, 5.6 high x 5.1 cm. wide (2.6/16 x 2 in.)

A ‘Long Term Parking’ 18ct gold pendant, a miniature of the artist’s sculpture depicting nine rows of cars set in concrete, further decorated with black, red, blue and green enamel, retractable suspension loop, number 19 from the edition of 50, inscribed 3011 1812/B, 19/50, signed Arman in the cast and stamped with Pierre Hugo's Société les Cyprès d'or and French eagle's head hallmarks, 5.7 x 1.8 cm. square (2 ¼ x 0.9/24 in.)

A ‘Pinceaux’ 18ct gold pendant with two suspension loops depicting 17 wet paint brushes and their brush strokes highlighted in dark and light blue enamel, number 19 from the edition of 25, inscribed 1809 3002, 19/25, signed Arman in the cast and stamped with Pierre Hugo's Société les Cyprès d'or and French eagle's head hallmarks, 6.1 high x 5.7 cm. wide (2 3/8 x 2 ¼ in.)

A ‘Tubes’ 18ct gold pendant with two suspension loops, squashed screw-topped paint-tubes arranged in two rows of eleven, the paint in shades of red enamel, number 19 from the edition of 25, inscribed 3014 1810/B, 19/25, signed Arman in the cast and stamped with Pierre Hugo's Société les Cyprès d'or and French eagle's head hallmarks, 7.6 high x 5.5 cm. wide (3 x 2 3/16 in.)

Provenance: Jan & Monique des Bouvrie.

Literature: C. Siaud, P. Hugo, Bijoux d'artistes, Hommage à François Hugo, Aix-en-Provence, 2001, another set illustrated pp. 210-15;

M.S. Newby Haspeslagh, Art to Wear, Jewellery by Post-War Painters and Sculptors, Didier Ltd., London, 2012, this set illustrated pp. 10-11, no. 6.

Note: The present cased and complete set of eight different pendants must be considered scarce, as many examples of the designs would have been retailed individually.

In order to cultivate maximum exposure for his creations, Arman collaborated with numerous specialised jewellers to include Argeco, Artcurial, Arthus-Bertrand, Filippini, F. & F. Gennari, and Pierre Hugo. Pierre Hugo had assisted his celebrated goldsmith father François Hugo since the late 1960s with the production of jewellery and sculptures in precious materials by, among others, Andre Derain Max Ernst, Pablo Picasso and Dorothea Tanning. Arman was the first artist that Pierre Hugo began working with after his father’s death, inaugurating a new chapter in the production of artists’ jewellery in Aix-en-Provence.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Harry Bertoia (1915-1978), A unique and substantial gong pendant, 1960s. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

hand-hammered white metal, stylised lower female torso decorated with a cylindrical coral bead attached by a gold rivet, together with a certificate by Val Bertoia, dated 28 October, 2014, pendant 12 cm. square (4 ¾ in.)

Provenance: Clarence Haack, Ventura, CA, USA.

Literature: M. S. Newby Haspeslagh, Jewelry by Contemporary Painters and Sculptors @50: 1967-2017, exh. cat., Didier Ltd., London, 2017, illustrated p. 26, no. 10.

Exhibited: 'Bent, Cast and Forged, The Jewelry of Harry Bertoia', Museum of Art and Design, New York, 3 May – 25 September 2016.

Note: Harry Bertoia first started making and indeed teaching jewellery while he was head of the metalwork department at the Cranbrook Academy of Art during the Second World War. As metal supplies dwindled during the war, Bertoia started to work out his ideas on a smaller scale, his jewels becoming maquettes with which to organise and develop his ideas. Like Calder, he set himself severe working limitations by only using cold connections, which meant he refused to use solder, preferring instead to use rivets, like the gold rod that holds the coral bead in place on this pendant. Of large and impressive scale, the pendant features a gently hammered surface, with finer hammering towards the edges, that appears inspired by prehistoric flint tools and arrowheads. To achieve this personality the silver was repeatedly hand-beaten heavily, reheated, and hand-beaten again to compress the crystalline structure and make for a very hard metal that vibrates and resonates when tapped. This process takes great skill and assuredness — too much beating and the silver becomes brittle. Reheat it too much it can melt or the surface become crizzled. Afterwards, this piece was given a deliberate dark patination through a process of chemical oxidisation. The pendant therefore incorporates sonic as well as sculptural properties, confirming the importance of Bertoia’s handcrafted jewellery alongside the vast portfolio of metal sculptures executed during his lifetime, from ‘Sonambient’ to ‘Bush’ forms, all meticulously executed to perfection.

This unique pendant is one of a group of unique Bertoia jewels from the collection of Clarence Walter Haack (1915-2010), whose company the International Metals Corporation and Halaco Engineering of Ventura, California, provided Bertoia with the metal alloys his employed in his sculptures. Bertoia would often travel to California to meet with Haack, where they would discuss business and seemingly jewellery too, as a drawing for a silver necklace with a gong central pendant appears in on the back of one of the company’s ledgers (M.S. Newby Haspeslagh, Jewelry by Contemporary Painters and Sculptors @50: 1967-2017, Didier Ltd, London, 2017, pp. 24, 27, no. 11).

.jpg)

Claude Lalanne (1925-2019), A ‘Hortensia’ necklace, circa 1990. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

18ct gold, front fastening, formed from articulated hydrangea flower petals arranged in a graduated manner, together with original case marked Arcurial, edited by Artcurial, Paris, number 13 from the gold edition of 30, 38 cm. long (14.15/16 in.), stamped on back of clasp with two French eagle's head hallmarks, 750, and stamped on the hook ARTCURIAL, 13/30, PT maker's mark, C. LALANNE and with French eagle's head hallmark.

Literature: M. Chapsal, Claude Lalanne, Bijoux, Sacs-Bijoux et La Montre-Oignon, Paris, 1996, another example illustrated p. 35.

Note: The jewellery created by Claude Lalanne, inspired by nature with a surreal twist, is among the best-known and most desired 20th Century jewellery by artists. Her contribution to jewellery design has been long celebrated and admired by collectors since before the artist’s collaboration with the visionary fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent, who did not hesitate to ask Ms Lalanne to design a series of jewellery designs to appear alongside his models for the 1969 season. The collection, which is today considered a pivoting and iconic moment in fashion history, featured bronze bust-shaped belts, breast plates, finger jewellery, earrings and others. The artist used flowers, buds, petals, leaves, twigs and tendrils retrieved from her own gardens as inspiration for her forms in galvanised in copper, combining the single elements to either create unique works or casts for multiples executed using precious materials. According to a price list from December 1992 the Hortensia necklace cost 54,000 FFr, while the silver or vermeil examples (from the single edition of 100 pieces) cost 9,200 and 10,200 FFr respectively, while the bronze edition of 250 examples were 7,800 FFr.

Surrealism and Fashion proved immediate companions, and this was especially true of Surrealist jewellery. Salvador Dalí’s lobster telephone became one of the most iconic pieces of surrealist design and this is continued in the pair of earrings fashioned in the form of melting telephone receivers. Constructed from fine bone-like gold, they are decorated with rubies and diamonds, and were produced to order around 1949. Hans / Jean Arp’s surreal sterling silver necklace conjures the image of a broken bottle-head which is set with polished cabochon carnelian and chrysoprase eyes. Two flat moustache-shaped link to either side of the long rounded oval links.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Salvador Dalí (1904-1989), ‘Persistence of Sound’, an important pair of Surrealist earrings, designed 1949. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

18ct gold, shaped in the form of melting telephone receivers, with clip and post fittings, at the top a facetted domed ruby with a double band of five and four small diamonds, above a kinetic paisley-shaped cabochon ruby drop, at the bottom a single band of four diamond diamonds, a cabochon emerald and a kinetic paisley-shaped cabochon emerald drop, produced by Alemany & Ertman Inc., New York, together with original fitted burgundy leather box, the interior lid lined in cream silk with purple velvet mount, 4.7 high x 1.6 cm. wide (1 7/8 x 0 5/8 in.), each with cast signature Dalí, each finding stamped 18K.

Literature: L. Livingston, Dalí, A Study of his Art-in-Jewels, The Collection of the Owen Cheatham Collection, New York, 1959, pp. 34-5, no. XII for the original pair from 1949;

S. Dalí, M. Auger and O. Tusquets, Dalí Jewels – Joyas, The Collection of the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation, Salvador Dalí Foundation, Figueres, 2001, for the original pair from 1949 pp. 13, 58-61;

D. Venet, From Picasso to Jeff Koons, The Artist as Jeweler, exh. cat., the Bass Museum of Art and the Museum of Arts and Design, Miami and New York, 2011, pp. 78-79 for the pair from the collection of Audrey Friedman;

M. S. Newby Haspeslagh, Jewelry by Contemporary Painters and Sculptors @50: 1967-2017, exh. cat., Didier Ltd., London, 2017, this pair illustrated p. 44, no. 33;

D. Venet, Bijoux d'Artistes de Calder à Koons, La Collection Idéale de Diane Venet, exh. cat., Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paoris, 2018, this pair illustrated pp. 66-7, no. 58;

P. Stroppiana, Scultura Aurea, Gioielli d'Artista per un nuovo Rinascimento, exh. cat., Palazzo Ducale, Urbino, 2019, this pair illustrated p. 83;

K. Wouters, J. Verlinden and K. Hendrix, Wonderkamer II: Wouters & Hendrix, exh. cat., DIVA, Antwerp, 2019, this pair illustrated pp. 38, 42, no. 67.

Exhibited: ‘From Picasso to Jeff Koons, The Artist as Jeweler’, the Bass Museum of Art, Miami, 15 March – 21 July 2011 and the Museum of Arts and Design, New York, 20 September – January 8, 2012;

‘Bijoux d'Artistes de Calder à Koons’, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, 7 March – 9 September 2018;

‘Scultura Aurea, Gioielli d'Artista per un nuovo Rinascimento’, Palazzo Ducale, Urbino, 31 May – 8 September 2019;

‘Wonderkamer II: Wouters & Hendrix’, DIVA, Antwerp, 13 September 2019 – 16 February 2020.

Note: “The ear is a symbol of harmony and unity: the telephone design a reminder of the speed of modern communications - the hope and danger of instantaneous exchange of thought”.

Salvador Dalí

(L. Livingston ed. 1959, p. 34)

Salvador Dalí’s first jewellery designs appeared in Vogue in March 1937, with a further four (from the total of six) unique designs, executed for the Duke Fulco di Verdura, following in Vogue July 1941, in an article entitled ‘Dali’s Dream of Jewels’. These unique examples were subsequently exhibited November 1941 – January 1942 at the Salvador Dalí exhibition at MoMA, before travelling onwards to eight other US cities. By 1943 these items had entered private collections and were not exhibited again. When Dalí and his wife Gala came to New York for their annual visit they resided in style in the St Regis Hotel, which is how they met the Argentinian-born society jeweller Carlos Alemany, who had a small shop in the foyer’s mezzanine. Alemany had previously purchased one of Dalí’s early paintings, and in 1949 he approached the artist to design some jewellery.

The initial group of five jewellery designs commissioned by Alemany, at the cost of $5000, included the design for these ‘Persistance of Sound’ earrings. The commission needs to be contextualised in the light of the 1942 MoMA exhibition, and within the immediate post-war environment of New York, with many of Europe’s avant-garde artists, designers, musicians and architects having emigrated from Europe since the late 1930s. Therefore, this was a richly cultural, and indeed financially wealthy environment – suitably positioned to embrace Dalí’s luxurious designs that incorporated precious metals and valuable gemstones – and when Surrealism and Biomorphic Modernism remained the dominant artistic movements, before the iconoclasm of Abstract Expressionism that was to soon follow. In order to finance the project Alemany partnered with Eric Ertman, a Finnish shipping magnate, and together they had the designs copyrighted between 1949 and 1954 — the first jewellery designs ever to be so in the United States. These jewels were just the beginnings of a collaboration between Alemany & Ertman and the artist that endured throughout the 1950s and that eventually produced in the region of 50 jewellery designs. Some were unique and others were made to order.

Dalí’s interest in fashion and ornamentation had been cultivated during the 1930s, encouraged by, amongst others, Elsa Schiaparelli - for whose Place Vendome boutique he delivered one of his famous ‘Lip’ sofas, and with whom he collaborated on numerous garments and textiles, including the celebrated ‘Torn’ dress of 1937, now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. By 1944, Dalí’s own designs for ‘dream vs, reality’ dresses had been published in US Vogue, illustrating that his interests in costume and jewellery designs were parallel, and by turn an essential means of expression adjacent to painting. The imagery of this rare cased pair of earrings, the title of which references one of Dalí’s most celebrated paintings, ‘The Persistence of Memory’ (1931), are quintessentially, essentially Dalí-esque – the notion that a telephone receiver should be miniaturised, partially ‘melted’, and reimagined as earrings is no less mischievous than his concept for the Lobster Telephones created for Edward James at Monkton, Sussex, in 1936-37.

Another pair of ‘Persistence of Sound’ earrings, originally acquired from Alemany in 1953, is today in the collection of the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation in Figueres, Spain.

.jpg)

Jean (Hans) Arp (1886-1966), A ‘Tête de bouteille et moustache’ necklace, designed 1960. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

925 sterling with broken bottle head pendant set with polished cabochon carnelian and chrysoprase eyes, and with a flat moustache-shaped link to either side, joined by long rounded oval links with hook fastening, produced by Johanaan Peter Ein Hod, Israel, number 16 from the edition of 100, pendant 7.8 high x 5.5 cm. diameter (3 1/16 x 2 1/8 in.), overall 48.5 cm. long (19 in.), stamped on reverse DESIGN BY Arp, 16/100, PETER EIN-HOD, MADE IN ISRAEL, ST 925.

Literature: G. Bott, International Ausstellung Schmuck, Jewellery, Bijoux, exh. cat., Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt, 1964, another example illustrated, no. 6;

Jewelry by Contemporary Painters and Sculptors, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1967, another example illustrated, no. 4;

M.S. Newby Haspeslagh, Jewelry by Contemporary Painters and Sculptors @50: 1967-2017, Didier Ltd., London, 2017, this example illustrated pp. 22-23, no. 5.

Note: German-French artist and poet Jean (Hans) Arp was a prominent abstract artist and known today as one of the founders of Dadaism. Born in Strasburg, where it attended the Ecole des Arts et Métiers, Arp later moved to Weimar and finally to Paris where he studied at the Académie Julian. Here, Arp became involved with the Dada movement and the circle of artist frequenting the Cabaret Voltaire. A practiced artist in collages and sculpture, Arp became interested in jewellery design only in his mature years, the pieces created easily recognisable as part of his oeuvre of biomorphic forms with soft contours. This necklace and its companion brooch called “Profil” were designed in 1960 by Arp to help his fellow Dada artist Marcel Janco raise funds for an artistic community that he had set up in a deserted Palestinian Arab village at Ein Hod, in the foothills of Mt Carmel in Israel. The jewels themselves were made by Johanaan Peter in an edition of 100 for both. The first gold jewellery Arp designed were half a dozen decoupage pendants made in editions of six by François Hugo in Aix-en-Provence and exhibited after he died at Le Point Cardinal, Paris, in 1967, alongside other jewellery and sculptures in precious metals designed by Andre Derain, Max Ernst, Picasso and Dorothea Tanning.

French post-war jewellery is encapsulated by three very different personalities - Georges Braque’s textured gold chain confers an ancient, Giacometti-esque authority, the pendant cartouche with red-enamelled detail, perhaps a phoenix, suggestive of post-war reconstruction. Georges Braque devoted the last two years of his life to designing jewellery when he took a fancy to creating a cameo ring for his wife on the occasion of her 80th birthday. By contrast, César’s life-sized matchstick pendant is pure Pop Art, a disposable wooden stick, of no intrinsic value, now made precious in gold. Niki de St Phalle’s The Key is an 18ct gold key with polychrome enamel dots on one side, and black enamel on the other, with the words “the key” written using diamonds. To be worn on a string around the neck, The Key fuses Pop Art with the bold energy of 1980s design.

Georges Braque (1882-1963), A ‘Procris’ pendant and ‘Minos’ chain, 1963. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

18ct textured gold pendant with red enamel details depicting a standing bird, 18ct gold chain of 23 textured links with rings at both ends, produced by Heger de Löwenfeld, the pendant number 24 and the chain number 15 from the respective partially executed editions of 75, pendant 3.7 high x 5.2 cm. wide (1 ½ x 2 1/16 in.),chain 69 cm. long (27 1/8 in.), reverse of pendant inscribed BIOUX DE BRAQUE, PROCRIS, R24/75, LP3037, HEGER DE LOEWENFELD and stamped French eagle's head hallmark, OR 750, one chain link inscribed BIJOUX DE BRAQUE, MINOS, R15/75, LP2648, another stamped OR 750 and with two French eagle's head hallmarks.

Literature: R. de Cuttoli, H. de Löwenfeld, Métamorphoses de Braque, Gouaches, bijoux, livres d'art, lithographies, Paris, 1989, another example illustrated pp. 50, 52;

M. S. Newby Haspeslagh, Jewelry by Contemporary Painters and Sculptors @50: 1967-2017, exh. cat., Didier Ltd., London, 2017, this example illustrated pp. 30-31, no. 15;

P. Stroppiana, Scultura Aurea, Gioielli d'Artista per un nuovo Rinascimento, exh. cat., Palazzo Ducale, Urbino, 2019, this example illustrated p. 55.

Exhibited: ‘Scultura Aurea, Gioielli d'Artista per un nuovo Rinascimento’, Palazzo Ducale, Urbino, 31 May-8 September 2019.

Note: Georges Braque, pioneer of Cubism and one of the century’s most celebrated artists, chose to dedicate the last years of his life to designing jewellery. His initiation into this medium was pioneered by his design for a cameo ring for his wife’s birthday, which featured the head of Hécate, a miniature version of his painting “Tête Grecque” of around 1957. He was subsequently introduced to the lapidary and jeweller Héger de Löwenfeld and together they entered such a close relationship that Braque referred Löwenfeld as “the extension of my hands”.

The Classical personality of this important and highly personal design, with strong reference to allegory and the Antique, reveals parallels to the sinuous bronze lamps, tables and chairs created around the same period by Diego Giacometti, or the films of Jean Cocteau, most specifically Orphée (1950), or the literature of the post-war Existentialists, all of which have intellectual origins that trace direct lineage to the Parisian Surrealists of the early 1930s.

According to the Greek myth, Procris was tested for her fidelity by her husband Cephalus who tempted her with jewels. At first she resisted but later succumbed, at which point Cephalus revealed himself and banished her. Annotations on the original gouaches for the pendant and the chain show that they were intended to be worn together, while the letter R engraved in front of the edition number refers to the colour of the enamel, in this case red or rather rouge. Other colours were available: V for vert, B for bleu, Bl for blanc and RR for rouge rose.

In all, Braque designed over 100 items of gold jewellery for Löwenfeld to create, and yet what is today largely forgotten is that these works were exhibited to great acclaim at 34 locations round the world between 1963 and 1971, and visited by just under a million people. Furthermore, by way of recognition Heger de Löwenfeld was made baron by the French government.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), A rare ‘Personnage aux bras levés’ brooch, cast after 1962. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

silver-gilt brooch cast with the figure of a man with typical elongated limbs in sunken relief, cast by Pierre Monsel, 4 cm. diameter (1 9/16 in.), stamped on the edge with French boar's head hallmark and Pierre Monsel maker's mark PM either side of a chalice.

Literature: G. Wood, Surreal Things, exh. cat., Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 2007, this lot illustrated p. 133;

D. Venet, Bijoux d'Artistes de Calder à Koons, La Collection Idéale de Diane Venet, exh. cat., Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, 2018, this lot illustrated p. 89, no. 85.

Exhibited: ‘Surreal Things’, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 29 March – 22 July 2007 then travelled to; Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, 29 September 2007 – 13 January 2008 and Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, 3 March – 7 September 2008;

‘Bijoux d'Artistes de Calder à Koons’, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, 7 March – 9 September 2018;

‘Jewellery - material craft art’, Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum, Zurich, 19 May 2017 – 22 October 2017.

SOTO : This lot is registered in the Fondation Alberto and Annette Giacometti online Database as no. 1241.

In his biography of Alberto Giacometti, Yves Bonnefoy notes how in 1929 Giacometti took over the decoration of the Parisian boutique of Italian couturier Elsa Schiaparelli, as well as making jewellery and other elements to be integrated in the pieces the designer was making for the Élite Parisienne. This collaboration with Schiaparelli took place before the one of Salvador Dalí and Jean Cocteau, but whilst Dalí was later feted for his work, Giacometti’s was “considered to be a kind of moral decay” (“Alberto Giacometti. A Biography of His Work”, Paris 2001, p. 553). At a financially challenging time in the artist’s career, the opportunity presented means of earning money. The figure modelled on this silver-gilt brooch presents all the common traits typical of Giacometti’s work. Other examples of such forms by Giacometti can be found today on a perfectly conserved wool jacket made by Elsa Schiaparelli, previously in the collection of Marlène Dietrich, now in the collection of the Deutsche Kinemathek Museum für Film und Fernsehen, Berlin (inv. no. 70624); on this period couture piece, three bronze buttons prominently dominate the front of the jacket, each depicting figures in similar positions.

Giacometti also created similar medallion-shaped forms in occasion of another collaboration, this time with interior decorator Jean-Michel Frank, for which the artist created standard lamps, candle holders and other elements to complement Frank’s own designs. In this instance, Giacometti’s bronze medallions were used as complements to architectural features, such as mantelpieces, in interiors of traditional and neo-classical inspiration. Although not celebrated at the time, the work of artist was in its aestheticism ahead of his time but fully accepted and sought after by creative minds with a certain artistic sensitivity for its versatile nature.

.jpg)

César Baldaccini (1921-1998), A unique ‘Compression’ pendant, 1970s. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

comprising elements in 18ct yellow and rose gold, with a suspension hole for a cord to pass through, 5.7 x 0.4 x 0.3 cm (2 ¼ x 0.5/24 x 0 1/8 in.),engraved César in the middle of one side and stamped with three hallmarks for foreign gold, mixed 18ct gold, and Pascale Morabito maker's mark below: ET in a square, MD in rectangle, and BM separated by a pair of callipers.

Note: A fervent supporter of the Nouveaux realistes movement, French sculptor César approach to art involved, from his early years as a sculptor, the use of discarded elements of metal to create complex forms. Of great importance to the artist’s artistic development were his iconic ‘Compressions’ works, starting from 1960, the subject of which were motorbikes, automobile bodies and, discarded metal compressed using a hydraulic crushing machine. A decade later he started applying the same creative process to miniature compression pendants or ‘microsculptures’ using pieces of scrap gold and silver, often still set with diamonds and other gemstones. These elements were crushed together in such a way that all the pieces were internally locked together without any soldering necessary to maintain them in place. Each jewel was made unique, often born out of recycled or up-cycled jewellery, medals and watch fragments, made in collaboration with Gérard Blandin and Pascal Morabito in Nice. Pascal Morabito first worked with César in occasion of his first exhibition of gold compressions, which took place at the Place Vendôme, Paris, in 1970. The exhibition, entitled "Pas de quartier pour Cartier" included examples of ‘compressions’ of three crushed Cartier jewels: a Tank watch, a triple ring, and a marine chain.

.jpg)

Niki de St Phalle (1930-2002), A ‘The Key’ pendant, 1991. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

18ct gold pendant, one side decorated with black enamel with the legend "THE KEY" spelt out in tiny diamonds, the other with polychrome enamel splashes, edited by T.M., Paris, from the edition of 30, together with original fitted suede leather jewellery box in bright fuchsia, the inside of the lid with facsimile signature Niki de Saint Phalle, and editor's mark T.M. Paris, 7.8 long x 4.25 cm. wide (3 1/16 x 1 5/8 in.), jewellery box 15 cm sq. (5 7/8 in.), incised to one side 5/30, Niki de Saint Phalle, 1991, stamped near the teeth with editor's mark T.M. Paris, 750 hallmark along the edge, two Italian hallmarks 121 MI, 1277 MI and a French eagle's head.

Provenance: Gift of the artist;

Private collection, New York.

Literature: D. Küppers, Künstlerschmuck, Objets d'art, Von Picasso bis Warhol, Künstlerschmuck der Avantgarde, exh. cat., Museum fu¨r Angewandte Kunst and Stiftung Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Cologne and Duisburg, 2009, another example illustrated p. 148;

Bodyguard, Une collection priveé de bijoux d'artistes, exh. cat., Passage de Retz, Paris, 2010, another example illustrated p. 56;

E. Guigon, Bijoux d'artistes, Une collection, exh. cat., Galerie du Crédit Municipal, Paris, 2012, another example illustrated p. 141;

P. Stroppiana, Scultura Aurea, Gioielli d'Artista per un nuovo Rinascimento, exh. cat., Palazzo Ducale, Urbino, 2019, this example illustrated p. 163.

Exhibited: ‘Scultura Aurea, Gioielli d'Artista per un nuovo Rinascimento’, Palazzo Ducale, Urbino, 31 May – 8 September 2019.

Note: De Saint Phalle designed her first jewellery in 1971 in collaboration with GianCarlo Montebello in Milan, and again in the late 1980s with Diana Küppers in Mülheim. This gold and enamel key dates to this latter period, and is a perfect example of her characteristic, colourful Pop style. Conceived to be casually, informally worn around the neck suspended from a thong, with this design De Saint Phalle inverts to playful effect the youthful tradition of wearing one’s own housekey around one’s neck.

Artists from the Americas pioneered innovative expressions within jewellery design. Alexander Calder’s brooches were often made as gifts for friends, as in the unique silver initials showcased in Art to Wear, which were made for Kurt Valentin to give as a gift. Taking its appearance as if from a fibula on a Roman cloak, the single stream of silver ribbon was hand hammered to form two mirrored ‘R’s that appear archaic, almost primitive. Venezuelan Jesús Rafael Soto saw how Calder had integrated time and movement in sculpture and wanted to attempt the same in painting. He began creating pieces based on repetitions, rotations, serializations and progressions, which would become the foundation on which his future work would stand. The pair of large rhodium-treated silver and silver-gilt earrings see him explore three dimensional objects, becoming kinetic sculptures in their own right. Louise Nevelson’s unique rectangular pendant looks like an extension of her oeuvre painted in her typical matt black – a condensed, sculptural façade ready-to-wear.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Alexander Calder (1898-1976), A large and unique brooch, circa 1948. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

hand-hammered from a single piece of white metal wire and with a steel prong fastening, 5.2 high x 12 cm. wide (2 1/16 x 4 ¾ in.).

Literature: M. S. Newby Haspeslagh, Jewelry by Contemporary Painters and Sculptors @50: 1967-2017, exh. cat., Didier Ltd., London, 2017, this lot illustrated no. 29.

Note: Simplicity of equipment and an adventurous spirit in attacking the unfamiliar or unknown are more apt to result in a primitive, rather than decorative, art. And somehow the primitive is usually much stronger than that in which technique and flourish abound.

Alexander Calder, 1943

The present brooch, of impressive large scale, was made by Calder around 1948 for Curt Valentin, the German-born New York gallerist, reputedly as a gift for the latter’s love interest. Of characteristic personalised form, this example benefits from symmetrical, mirror-backed ‘R’ initials yielded from a continuous ribbon of hand-hammered silver wire, anchored by a wrought steel pin. The scale is reassuring, suggestive of the functionality of Roman fibula or Antique cloak-clasps, and confirms the earnestness of Calder’s craft.

As a child, Calder improvised jewellery for his sister’s dolls from wire found discarded in the street, and later as a young artist living in New York in 1926, with neither clock nor wristwatch, fashioned a working, rooster-shaped sundial, again from scraps of wire. Whilst Calder’s later mobiles and sculptures rightly anchor public spaces or museum halls internationally, it is through the artisanal crafted artefacts, structures, domestic paraphernalia and personalised jewellery that the artist most reveals his poetry.

.jpg)

Jesus Rafael Soto (1923-2005), ‘Penetrabile’, a pair of large earrings, 1967. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020

rhodium-treated white-metal and part-gilded earrings, with clip fittings and loops designed to hang over the ears to afford extra support and stability; each earring with a long and shallow moveable horizontal rectangular box from the inside of which are suspended three rows of 23 thin kinetic rods, decorated with silver-gilt to the top half of one and the bottom half of the other, produced by GEM Montebello, Milan, from a first edition of 200 pairs (model JS/1), of which only 35 were executed, together with a certificate of authenticity from Giancarlo Montebello, overall 13.3 cm. (5 ¼ in.), pendant 6.9 cm. square (2 11/16 in.), stamped on the back of the earring, GEM, X, 800

Literature: L. Yarlow, Jewelry as Sculpture as Jewelry, exh. cat., Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 1973, another pair illustrated no. 124

Bijoux d'artistes, Artists' Jewellery, exh. cat., Galerie Sven, Paris, 1975, another pair illustrated, p. 13, no. 21;

D. Küppers, Künstlerschmuck, Objets d'art, Von Picasso bis Warhol, Künstlerschmuck der Avantgarde, exh. cat., Museum fu¨r Angewandte Kunst and Stiftung Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Cologne and Duisburg, 2009, another pair illustrated p. 152;

D. Venet, From Picasso to Jeff Koons, The Artist as Jeweler, exh. cat., the Bass Museum of Art and the Museum of Arts and Design, Miami and New York, 2011, another pair illustrated p. 220;

D. Venet, Bijoux d'Artistes de Calder à Koons, La Collection Idéale de Diane Venet, exh. cat., Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, 2018, another pair illustrated pp. 180-81, no. 188;

M. S. Newby Haspeslagh, From the Surreal to the Kinetic, Jewellery by Latin and South American Artists, exh. cat., Didier Ltd., London, 2018, this pair illustrated pp. 72-73, no. 67 and front cover;

P. Stroppiana, Scultura Aurea, Gioielli d'Artista per un nuovo Rinascimento, exh. cat., Palazzo Ducale, Urbino, 2019, this example illustrated p. 167;

K. Wouters, J. Verlinden and K. Hendrix, Wonderkamer II: Wouters & Hendrix, exh. cat., DIVA, Antwerp, 2019, this pair illustrated p. 94, no. 136.

Exhibited: ‘Scultura Aurea, Gioielli d'Artista per un nuovo Rinascimento’, Palazzo Ducale, Urbino, 31 May – 8 September 2019;

‘Wonderkamer II: Wouters & Hendrix’, DIVA, Antwerp, 13 September 2019 – 16 February 2020.

Note: Jesus Rafael Soto was one of the most important exponents of optical and kinetic art. Between 1942 and 1947 he studied at the Escuela de Artes Plásticas in Caracas alongside Carlos Cruz-Diez, and later directed the Escuela de Bellas Artes in Maracaibo from 1947 to 1950. Similarly to many other South American artists, Soto later moved to Paris where he held his first show in 1956. In 1966, in occasion of the XXXIII Venice Biennale, Soto presented in the Venezuelan pavilion the first of his iconic Penetrabile installations, consisting in a curtain of fine oscillating wire rods suspended in the through which people could walk. Within a couple of years Soto developed the design of the Penetrabile earrings together with the Milanese artistic jeweller GianCarlo Montebello which, similarly to his large-scale installations, featured a multitude of kinetic rods free to move and swish with the movement of the wearer. Between 1967 and 1968 Soto collaborated with Montebello to create a total of four jewellery designs as part of the project. In those years GEM Montebello was collaborating with over fifty internationally recognised artists to produce a new generation of radical, experimental models, integral to the body of work of each respective artist. To guarantee availability to the audience, GEM Montebello intended to issue a large number for each design however only the production of a few of these editions were completed. Following a robbery in 1978, GianCarlo Montebello decided to discontinue the production of jewellery by artists and shift the focus of the firm towards different objectives.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Louise Nevelson(1899-1988), Unique pendant, 1980-1985. Estimate on request. © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

painted wood, of rectangular shape with rounded corners, the top set with a selection of wood off-cuts and mouldings and even half a clothes peg, all painted in the artist's typical matt black and highlighted with white metal and with suspension loop, 12 high x 7.9 wide x 3.2 cm. deep (4 ¾ x 3 1/8 x 1 ¼ in.), reverse with applied strip of white tape numbered with Pace Wildenstein’s, New York, inventory number 28406 in black ink.

Provenance: Estate of the Artist (no. 50040);

Pace Wildenstein, New York (no. 28406).

Literature: M. S. Newby Haspeslagh, Paint it Black, The Jewels of Louise Nevelson, Didier Ltd., London, 2019, illustrated p. 55, no. 21.

Note: Recognition for this renowned sculptress of ground-breaking sculptural environments came only in middle age when in 1957 aged 58 Louise Nevelson's exhibition “The Forest” at the Grand Central Moderns Gallery received enthusiastic reviews and success then quickly followed. Nevelson created bold, non-figural assemblages formed from scraps of wood mostly scavenged from the streets of New York, or from pieces she had cut with unconventional tools like scissors. These she would build up into monumental structures, which she would paint in a monochrome colour, usually matt black, to create her own brand of minimalism. And she applied these principals when she made jewellery, initially for herself to wear. She was depicted often wearing her own jewellery in contemporary photographs but they are so much part of the persona she presented that these large black sculptural adornments blend in to become part of the whole. Her regard was so high that her black painted wood and gold earrings were used as the cover illustration for the Museum of Modern Art’s ground-breaking international traveling exhibition, Jewelry by Contemporary Painters and Sculptors in 1967, the first exhibition devoted solely to artists’ jewellery.

Art to Wear encourages viewers to explore a piece of jewellery not just as an expression of its materiality but as an extension of an artist’s oeuvre, a site of experimentation and artistic freedom.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F15%2F12%2F119589%2F96191999_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F02%2F05%2F119589%2F32528116_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F74%2F57%2F119589%2F32152192_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F18%2F63%2F119589%2F128563279_o.jpg)