Under the Hammer Highlights From Eternal Resonance: Music in Chinese Art

Photo Bonhams.

HONG KONG - Music has played many vital roles throughout Chinese history, be it ritual, spiritual, social of for leisure. Bonhams is delighted to present Hong Kong’s first-ever fine Chinese works of art thematic auction dedicated to music. The sale of Eternal Resonance: Music in Chinese Art, to be held on 1 December 2020, surveys a vast range of music-themed works spanning from the Bronze age to the present time.

Discover our highlights from the auction, from an archaic bronze drum and ritual bells to bamboo flutes and works of art embellished with musical elements in jade, porcelain, lacquer, painting, calligraphy, cloisonné-enamel and many more.

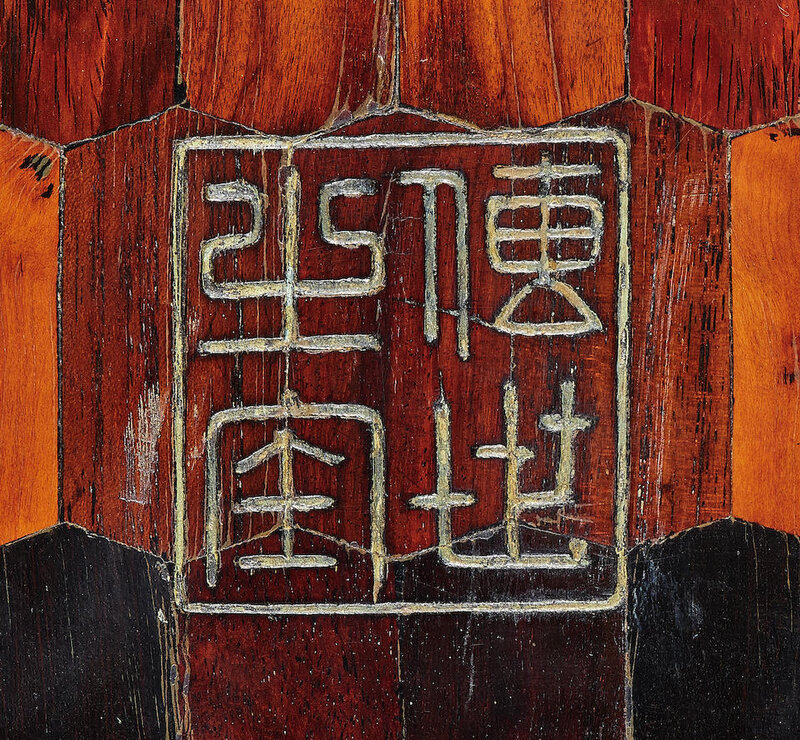

Lot 13. 'Taigu Yuanyin': An importand and rare 'Confucius-style' huanghuali and zitan-inlaid 'hundred-patch' Guqin, Ming Dynasty; 117cm (46in) long, 18cm (7in) wide. Estimate: HK$ 1,500,000 - 2,000,000 (US$100,000 - 150,000). Photo Bonhams.

Superbly constructed with various precious woods of warm and dark hues such as zitan, huanghuali, and hongmu cut hexagonally imitating Buddhist patchwork vestments, the flat elongated body with two waisted sections on both sides, the top with thirteen inlaid mother-of-pearl studs ( hui), seven strings threaded through tasseled jade pegs ( qinzhen) running over the top and tied to either of the two button-like 'goose-feet' ( yanzu) on the back, with two rectangular openings, the large one termed 'dragon pool' ( longchi) and the smaller 'phoenix pond' ( fengzhao), the underside bearing an inscription ' Tai gu yuan yin' or 'Harmony of Remote Antiquity', and the seal ' Chuan shi zhi bao', 'Treasure passed down the generations', box. Within the Chinese traditional musical instrument ensemble, the qin holds principal place with its history stretching from at least as early as the Zhou dynasty (and possibly earlier) to this date. In 2003, the qin was declared by UNESCO to be a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Yu Bosun and the present owner, 1981.

Published and Illustrated: Li Boqin, Zhongguo guqin zhenshang, Beijing, 1995, p.32, pl.11 Liu Qin, 115 Years of Memorial Birth Celebration for Mr. Chu Tunan, Beijing, 2014, p.131Liu Qirong, 'On the Dating of Qin Zithers of a Hundred Patches (baina qin) with Hardwood Marquetry' in Journal of Gugong Studies, 2015, May, pp.80-85.

Note: This Zhongni style (also known as 'Confucius-style' as this was supposedly the form of qin which the Sage played on) guqin, decorated with various precious woods cut hexagonally, was crafted using an extremely rare technique known as 'bai na' (which may be translated as 'hundred patch'), referring to the patchwork vestment worn by Buddhist monks.

At present, there are only two known bai na constructed qins in China's public museums that are similar in age and craftsmanship to the present lot. One is the Ming dynasty qin named 'E'mei song' (literally, 'Pine of E'mei [Mountain]') in the Palace Museum, Beijing, similarly decorated in a hexagonal tortoise-shell pattern with zitan; see Zheng Minzhong, Gugong guqin tudian, Beijing, 2010, no.26. The other is the Ming dynasty qin named 'Yin Feng' ('Attracting Phoenix') in the Sichuan Provincial Museum, inlaid with wood and bamboo; see Songshi jian yi: Bashu diqu diancang guqin jingpin ji, Beijing, 2015, pp.66-69.

A Ming dynasty qin named 'E'mei song' (literally, 'Pine of E'mei [Mountain]') in the Palace Museum, Beijing. Image courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing.

The earliest mention of bai na style qins date from the Tang dynasty. Tang dynasty bai na style qins were purportedly made of the finest specially selected wutong wood, as Wei Xuan (active around 840 AD) records in his 'Liu Bin Ke Jia Hua Lu':

Mr Li Qian strove to use among the best silk and wutong wood, stitching and blending the various elements together, he called this the 'hundred patch' qin. Using snail shells for the hui [harmonic markers]. Its three sides are especially magnificent. The strings will not break for ten years.' See Xuehai leibian, Shanghai, 1920, p.10.

Today there are no known bai na qins from the Tang dynasty, except for the 'Jiu xiao huan pei' qin in the Liaoning Provincial Museum. However, the only part of this qin which uses inlaid wood is the sound absorber section. The Song dynasty saw the emergence of imitation bai na qins including inlaying wood block to the sound absorber section or simply carving a tortoiseshell pattern on the surface of re-lacquered wood. Examples can be seen in the Jilin Provincial Museum, with the 'Song feng qing jie' qin, Song dynasty, as well as the Song dynasty qin 'Kunshan jade' in the Ye Shimeng (1863-1937) collection, see related discussion by M.Z.Zheng, Bainaqin kao (The Study of Bai Na Qins)in his Lice ouluji: guqin jianding ji qita (The Connoisseurship of Guqin and Other Studies), Beijing, 2010, p.87.

In the late Ming dynasty qins were made of hexagonal wood sections and bamboo, also called bai na qin. However, these were merely decorative and considered unsuitable for playing. The Ming dynasty scholar Gao Lian (1573-1620) in 'Zunsheng bajian' wrote:

'Among those bai na qins, they are also made today. Sometimes they are made of leftover beautiful materials [that were too good to be just thrown away], and so were cut into pieces and used to make a qin that is extraordinarily beautiful. Among those made today, there are those which are patterned like a tortoiseshell, inlaid with tortoiseshell, ivory, scented wood, and various other woods, with patterns inlaid with bone. The shops are filled with these qins which are called treasure qins.' See Gao Lian, Zunsheng Bajian in Qianding Siku quanshu, 1782, juan 15, p.76.

After the late Ming period, more precious hardwoods came to be used in making qins. This was related to the rise and popularity of using precious hardwoods and zitan for furniture; for further discussion, of the qins 'Tai gu yuan yin ['Harmony of Remote Antiquity']' and the 'E'mei song', late Ming dynasty, see Liu Qirong, 'Shilun xiangqian yingmu 'bai na qin' zhizuo niandai', in Gugong xuekan, Beijing, 2015, May, pp.80-85.

Lot 1. A Rare and large archaic bronze ritual bell, yongzhong, Early Western Zhou Dynasty; 47.1cm (18 1/2in) high. Estimate: HK$ 400,000 - 600,000 (€ 43,000 - 65,000). Photo Bonhams.

Of slightly flattened barrel form, both exterior faces with three rows of nine projecting mei bosses evenly distributed and divided by bands of smaller bosses separated by zoomorphic scrolls, the flat top decorated with similar scrolls, the tapering collared cylindrical shaft with a suspension loop on one side, the bronze with light malachite and azurite encrustation, stand. (2).

Provenance: Paul E. Manheim (1906-1999), USA

Sotheby's New York, 16 September 2009, lot 101 (part lot).

Exhibited: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,1968-2009 (on loan).

Note: The present bell appears to be one of the earliest-known examples of two-tone bells with motifs decorated to indicate the striking point for a second tone. Bells of this type were made in graduated sizes to form a tuned set or bianzhong, 'chime'. Two-tone bells permitted a wider range of notes with a certain number of bells. According to the Zhou Li, (the Rites of Zhou) from the Eastern Zhou period, only Kings, Marquises and other selected aristocratic groups were entitled to possess such bronze bells, and the number of sets allowed varied according to different Royal titles.

Only a few sets of early Western Zhou yongzhong bells have been found in archaeological sites. Compare with a very similar set of four yongzhong bells (the largest 46.2cm high), found in 2013 in an early Western Zhou tomb of the State of Zeng in Yejiashan, Suizhou, illustrated in Suizhou yejiashan xizhou zaoqi zengguo mudi (Early Western Zhou Tombs of State of Zeng in Yejiashan, Suizhou), Beijing, 2013, pp.138-143, pl.68. Compare with three other sets of three yongzhong bells of a similar form and decoration but smaller size (the largest 43cm high); one set found in an early Western Zhou tomb of the State of Yu in Zhuyuangou, Baoji; another set found in a tomb of the State of Yu in Rujiazhuang, Baoji, both illustrated in Zhongguo yinyue wenwu daxi: shanxi Tianjin juan, (The Great Collection of Historical Relics of Music in China: Shanxi and Tianjin), Zhengzhou, 1999, pp.29-32, fig.1-2;and a third set of three yongzhong bells of similar form and decoration excavated in Pudu village, Xi'an, illustrated by M.Hayashi in In shū seidōki sōran, Shanghai, 2017, vol.1 Illustrations, p.383, fig.Bell 33. Both archaeological sites in the former States of Zeng and Yu were dated to the early Western Zhou period.

Bell, early Western Zhou, Yejia Shan, Hubei.

See also a single bronze yongzhong bell, Western Zhou period, in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in Collections of the Palace Museum: Bronzes, Taipei, 2007, no.90, p.136. See also two related bronze yongzhong bells with similarly decorated scrolls, excavated in Shandong Province, illustrated by Zhu Xiaofang, The Research into the Bells of Zhou Dynasty in Shandong Area, Shanghai, 2016, p.48, nos.2-5 and 2-6. Compare with a further set of bronze yongzhong bells, Western Zhou dynasty, but with later inscriptions, illustrated by Chen Peifen, Research on Xia, Shang and Zhou Dynasty Bronze Vessels: The Collection of the Shanghai Museum, Shanghai, 2004, pp.568-569.

Lot 5. A Rare lushan phosphatic-splashed brown-glazed stoneware drum, Tang Dynasty; 58.5cm (23in) long. Estimate: HK$250,000 - 350,000 (€ 27,000 - 38,000). Photo Bonhams.

The attenuated hourglass-shaped body moulded with seven bowstrings and covered in a finely speckled dark-brown glaze with milky-blue phosphatic splashes with irregular trails and spots, the interior covered with a similar glaze but without splashes, stopping short of the unglazed rim at both ends, box.

The present drum is a rare example of the phosphatic-glaze-splashed ware produced in Lushan County, Henan Province during the Tang dynasty. Its hourglass-shaped form was inspired from the jiegu, a waisted wooden musical instrument adopted by members of the Tang aristocracy from the Central Asian region of Kucha, as recorded in Tang dynasty literature by Nan Zhao, Jiegu lu (Records of Jiegu), Shanghai, reprinted 1958. Instead of being carried around, a ceramic drum such as the present lot, would have been placed on a wood stand, with drumheads made of animal skins. See a waisted sancai-glazed drum, and a surviving portion of leather drumhead, Tang dynasty, in the Shosoin Repository, Imperial Household Agency, Nara, Japan (acc.no.South Section 114 and 116).

Shards of similar phosphatic-glazed drums were found in the Duandian kiln site in Lushan, Henan Province, and were included in the Oriental Ceramic Society exhibition, 'Kiln Sites of Ancient China', London, 1980, Catalogue nos.403 and 404, and also in The Discovery of Ru Kiln, Hong Kong, 1991, pl.23 (bottom left).

A similar drum with slightly narrower waist, unearthed from the site of Daming Palace of Tang Dynasty, Xi'an, in 1982, which might have been used at the Tang court, is illustrated in Zhongguo yinyue wenwu daxi: Shaanxi Tianjin juan (Compendium of Chinese Musical Instruments: Shaanxi Province and Tianjin), Zhengzhou, 1999, p.120, fig.191.

Compare with a closely related phosphatic-glaze splashed black-glazed waisted drum, Tang dynasty, illustrated in The Complete Collection of the Treasures of the Palace Museum: Porcelain from the Jin to the Tang Dynasty, Hong Kong, 2007, p.204, no.189. It is more common to find ceramic drums produced by other kilns in Henan Province, such as the sancai-glazed drum in the Shosoin Repository. See also a pale-yellow-glazed drum, Tang dynasty, illustrated in ibid., Hong Kong, 2007, p.191, no.176; and a Cizhou sgraffiato 'flower' drum, Tang dynasty in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (acc.no.18.56.34).

Image courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing.

Image courtesy of Xi’an Antique Protect Archaeology Academy.

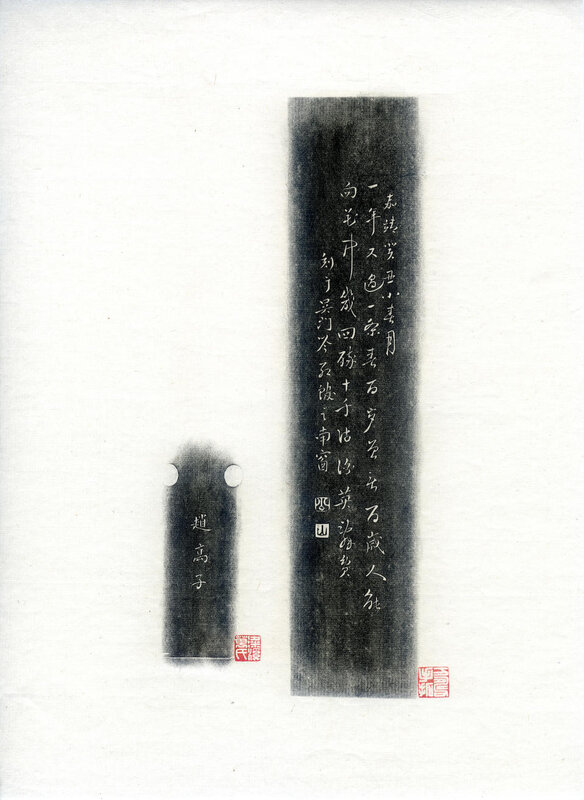

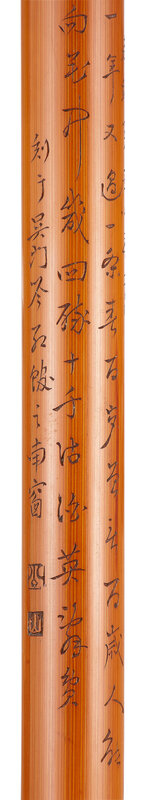

Lot 33. A very rare inscribed kunqu opera bamboo flute, dizi, Signed Zhao Gaozi, cyclically dated to the Guichou year, corresponding to 1553 and of the period; 72.2cm (28 7/16) long. Estimate: HK$ 200,000 - 300,000. Photo Bonhams.

Of long cylindrical form, carved from a length of bamboo with a bone flute head and end, each end carved in openwork with a butterfly, pierced along the length with a blowing hole, a membrane hole, six finger holes, two sound holes, and two opposing tassel holes underside, the upper part finely incised in cursive calligraphy with poetic inscriptions dated 'Spring month, Guichou year of Jiajing at Yinhong Pavilion of Wumen' the lower part incised with three characters Zhao Gaozi, the bamboo with a reddish-brown tone patina, box.

Published and Illustrated: N.Chow, The Literati Aesthetic, Hong Kong, 2018.

Note: The name Zhao Gaozi does not appear to be recorded. However, the finely-carved and dated inscription, especially with reference to Wumen (Suzhou), suggests that Zhao Gaozi was closely associated with a group of literati-artists active in Suzhou during the Ming dynasty, known as the Wu School. This was during the period when kunqu opera became the dominant form of theatre in Southern China. Bamboo dizi such as the present lot were used as the lead melodic instrument, as they were known for their lingering and more mellow lyrical tone.

The dizi is a transverse flute and one of the longest surviving major Chinese musical instruments used in many genres of Chinese folk music and opera. The earliest playable dizi was made of bone and excavated from the Jiahu Neolithic site in central Henan Province, attributed to the Peiligang Culture (circa 7000–5000 BC), now in the Henan Provincial Museum, illustrated by S.Yingying, zhongguo xinshiqi shidai chu tu yueqi yanjiu, (The Study of Excavated Musical Instruments of the Chinese Neolithic Period), Beijing, 2012, p.45, fig.2-21.

Although bamboo later became the common material for the dizi, very few examples would have survived due to the fragile organic nature of the material. See a related iron dizi, Ming dynasty, of similar form in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in zhongguo yinyue wenwu daxi Beijing juan, (The Complete Collection of Chinese Musical Instruments Cultural Relics in Beijing), Zhengzhou, 1999, fig.1-14-1.

The box of the present lot is inscribed with a Kanshi (Sino-Japanese) poem on its cover, which can be translated as:

'Playing the flute in the breeze, the moon casts shadows on the fence; sweeping the snow and brewing tea, a few plum blossoms scatter on the edge of the fence.' Following is a signature which can literally be translated as 'Written by Ehu Shanren (Gako Sanjin in Japanese) at my friend's study in the breeze of pines, at a day when the summer heat has gone away.'

There were two Japanese literati known by the literary name of Gako Sanjin, referred to in the inscription. Both were active in the first half of the 19th century. One possibility is that it could refer to Matsuzawa Yoshiaki (1791-1861), a scholar of the classics and also a komamono (fancy goods) merchant; another possibility is that it refers to Gako Suzuki (1816-1870), a Nanga master, who learned painting at an early stage from the renowned Tani Bunchō (1763-1840). In many works he signed himself as Gako Sanjin. Compare with signatures on two of his works, one on a painting of 'Red Cliffs' in the collection of the Sakano Family, Joso, Japan (acc.no.0460); the other in a book by him in the National Diet Library, acc.no.toku 1-807.

The Japanese connection is not so unusual considering that during the late Ming dynasty there was an influx of musical instruments being brought into Japan. Wei Zhiyan (1671-1689), a native of Hebei Province, and a merchant who travelled between China, Japan, and Vietnam, was also an expert of classical Chinese music. He developed close connections with many Japanese scholars, monks, and émigré Chinese monks in Japan such as Ingen (1592-1673) who founded the Obaku Zen sect. His disciples recorded and compiled fifty pieces of music inherited from him in the Gishi gakuhu (Wei's Music Scores), which was published in Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto in 1768.

In 1780, Wei's disciple Iku Tsutusi compiled Wei's collection of di, xiao, sheng, gongs, pipa, yueqin and other instruments that he brought from China to Japan in the Illustrations of Wei's Musical Instruments.

Holes of Ming dynasty flutes are slightly closer to each other than those of flutes made in the Qing dynasty. Chinese bamboo flutes of the Ming dynasty rarely survived in China, however, they survived in Japan in relatively larger numbers. Compare with a closely-related bamboo dizi from the Hosokawa collection, in the Eisei Bunko Museum, Tokyo, illustrated by M.Hosokawa, Eisei Bunko meihinsen: bungu, Tokyo, 1978, p.129, where the author notes that although its form is related to the early Qing dynasty, the tight arrangement of the finger holes indicates a late Ming dynasty date.

Lot 29. Pu Ru (1896-1963), Sage playing qin. Ink and colour on paper, inscribed by the artist with a poem reading shideng lianyuqi, huanhui chumiaoming, niaofei choubuxia, dishou wangkongqing, signed Xinyu with three artist's seals, reading Songchao ke, Puru zhiyin, Jiangshan weizhu bizongheng, frame and glazed. 132.5cm (52in) high x 33.5cm (13 1/4in) wide. Estimate: HK$ 420,000 - 480,000 (€ 46,000 - 52,000). Photo Bonhams.

Published and Illustrated: Chew's Culture Foundation, A Fine Collection of 100 Chinese Painting of Hong–Gah Museum, 2006, p.104.

Note: The poem inscribed on the painting is included in Pu Ru's Xishan ji (Poems of Xishan) in a volume of his complete works, the Hanyu tang shiji (Poems of Hanyu Tang). It is titled Hutian ge (Pavilion of Hutian) and was written after a visit to Mount Tai in Shandong in Yimou year (1915). The poem may be translated as:

'Rocky ledges piercing the clouds,

Twisting and turning in the dark realm of apricot blossoms,

Birds fly up fearing they will not land again,

Looking down they see only the azure sky.'

The painting was executed with an unusual composition. The main figure, a sage playing a qin by a ledge, is not placed in the usual space in the lower section of a Chinese painting, but rather occupies the upper section. This immediately draws the viewer's eyes up to the musician, creating a sense of height and quiet solitude.

Compare with a joint work with Zhang Daqian (1899-1983) dated 1945, also inscribed with the same poem and depicting two sages on Taishan Mountain, in the Sichuan Provincial Museum, illustrated in the catalogue of the Liaoning Provincial Museum and Sichuan Provincial Museum, Daqian yu duanhuang sichuan bowuyuan cang zhangdaqian huihua jingpingji (Zhang Daqian and Dunhuang Caves: A Selection of Zhang Daqian's Painting), Shenyang, 2012, pp.140-141.

Lot 14. A unique Nanmu, Tongmu and lacquered qin table, Qinzhu, Designed by Jerry J.I. Chen. Wunian In Praise of Rectitude Qin table series, 2019, No.AC23.6219; 110cm (43 1/4in) long x 40cm (15 3/4in) deep x 68cm (26 3/4in) high. Estimate: HK$ 200,000 - 300,000 (€ 22,000 - 33,000). Photo Bonhams.

Published and Illustrated: Jerry J.I. Chen, Chunzai Design, Fujian, 2020, pp.246-249.

Note: 'To keep our mind free from defilement under all circumstances is called 'wu nian'.'

By Dajian Huineng (638–713 AD).

The Chinese word 'wu', which literally means 'nothingness', has different connotations. On one level, it can be interpreted as 'emptiness', so one has unlimited tolerance to accept all things. At another level, it represents a sense of 'infinity', when one reaches such a boundless state of tolerance.

The word 'nian' means 'to think of'. However, when putting the two words together as 'wu nian', the connotation does not form the meaning 'doing and thinking nothing'. On the contrary, it means 'to comprehend', which encourages one to behave with a free and purified mind; to have an authentic understanding of things, a clarity which one would see in a mirror.

Dajian Huineng (638–713 AD), also known as the Sixth Patriarch of Chan Buddhism and the central figure in the early history of Chan, once stated: 'To keep our mind free from defilement under all circumstances is called 'wu nian'.'

The phrase 'wu nian' is further considered to describe a state of mind that is free from impurities and restraints; and it can therefore represent a statement for freedom of conscience. As it is written in the Diamond Sutra: 'one should not give rise to the purest aspiration whilst still abiding in form, in sound, odour, taste, touch or concepts. One should give rise to the purest aspiration when not abiding in anything.'

The present qin table is made from carefully selected nanmu wood, with the single-top panel of antique well-figured tongmu wood enclosed within a wide, straight-edged frame. The underside of the table is set with another single panel in tenon-and-mortise joints to form the 'resonator', both panels are reinforced by transverse braces, each narrow side of the 'resonator' with a slim 'fish-eye' aperture to amplify the sound waves, all standing on slender corner legs of slightly-tapering square section.

The exterior of the 'resonator' is further decorated by applying multiple layers of raw lacquer, polished and wrapped with a hemp cloth enhanced with further coatings of lacquer, which creates a mixture of purple and brown textures elegantly contrasting with the chestnut ground.

Refined and restrained in form, the present table represents a contemporary interpretation of the highest standards in classical Chinese furniture. The lower part of the table displays a simple design in the apron and waist, presenting a sense of simplicity, fluidity and superb balance, made possible by sophisticated and concealed joinery. The essence of literati taste is encapsulated by its design, making it a perfect table on which to play the guqin.

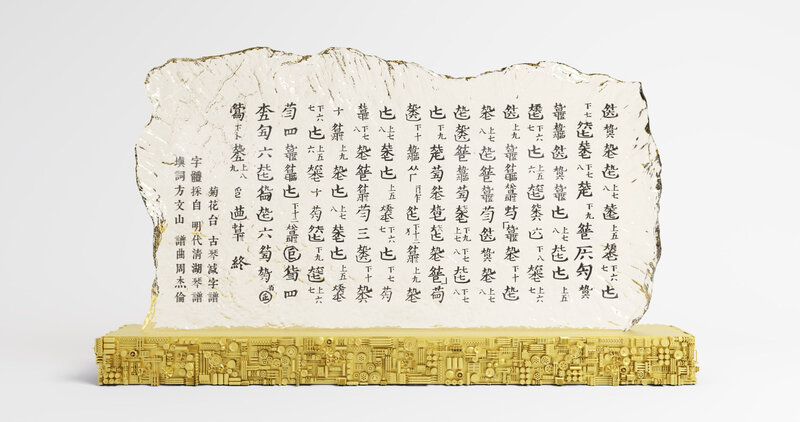

Lot 51. Vincent Fang, Juhua Tai (Chrysanthemum Terrace), October 2020. Signed by the artist. Epoxy, cast resin, polyvinyl chloride and mixed media. Edition:1/4; 175cm (68 3/4) long × 28cm (11in) wide × 104cm (40 3/4in) high. Estimate: HK$ 120,000 - 150,000 (€ 13,000 - 16,000). Photo Bonhams.

Note: Juhua Tai (Chrysanthemum Terrace), was written for Zhang Yimao's movie Curse of the Golden Flower (2006) which was adapted from William Shakespeare's Hamlet, and was also included in Jay Chou's album Still Fantasy published in the same year. The current work is inspired by jianzi pu, a unique form of tablature for guqin. Jianzi, literally 'abbreviated characters', consisting of strokes from different characters, was developed from wenzi pu or full-character tablature detailing the tuning, finger positions and comprising a step-by-step method and description of how to play a piece. Jianzi pu dramatically reduced the length of a guqin piece, whilst increasing the accuracy and efficiency of the guqin music notation.

The artist invited a young guqin musician, Ms Zhang Lu, who graduated from the Central Conservatory of Music, China, in 2011, to convert the music of Juhua Tai which was written by Jay Chou into jianzi pu. He carved the tablature on a glassy transparent plaque and placed it on a yellow industrial-style stand, creating another artful combination of Chinese classic and modern media, just as he has done in his writing.

Vincent Fang (b.1969), a Taiwanese multi Golden Melody Award winner lyricist, is best known for his collaboration with singer-songwriter Jay Chou. His work is rooted in the rich tradition of Chinese literature, reinterpreting the classic language to a modernist form. Fang is considered to be at the forefront of 'China Wind music', a fusion genre which became popular since the 2000s, combining modern rock and contemporary R&B together with traditional Chinese music.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_78c699_440320998-1657454638357882-17494889713.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240421%2Fob_1dddd2_438878301-1654314112005268-81048289869.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240421%2Fob_df8c96_438328730-1653747745395238-34643333091.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240417%2Fob_961e87_437772831-1653147868788559-54808306367.jpg)