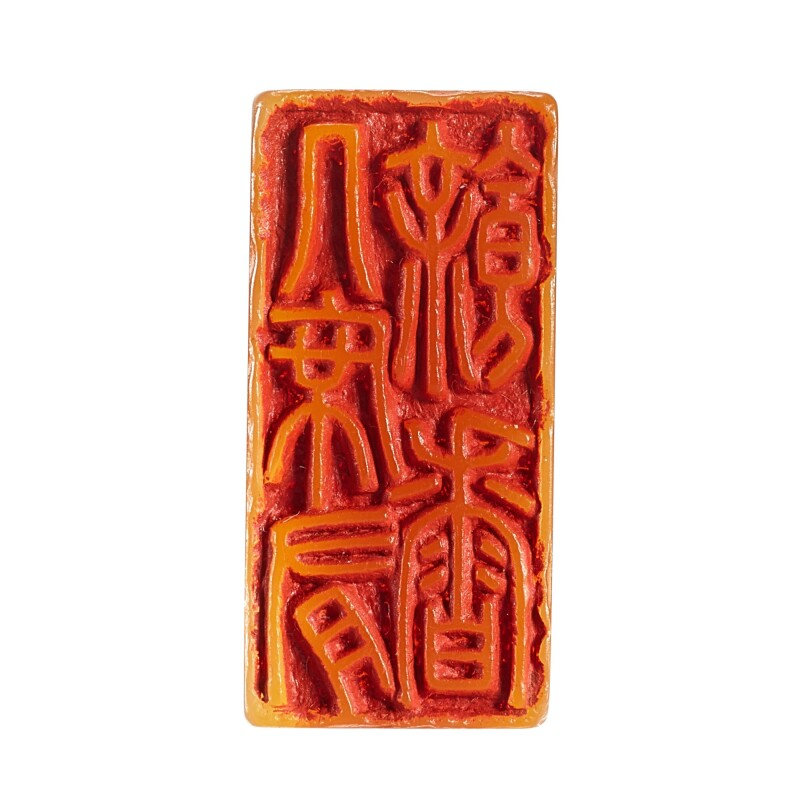

An imperial tianhuang seal, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period (1736-1795)

Lot 3650. An imperial tianhuang seal, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period (1736-1795); 2.6 by 1.2 by h. 4.1 cm; 33.44 gr. Lot sold: 6,467,000 HKD (Estimate: 2,600,000 - 3,200,000). © 2021 Sotheby's

the rectangular seal surmounted by a finial masterfully carved to depict a scroll resting atop a brocade-covered set of books, all tied together with a ribbon, the seal face carved with five-character inscription reading jixi you yuxiang ('Fragrance lingers among the desks and mats'), the stone of a rich honey-orange colour.

Provenance: Collection of Matsumoto Tadahira.

The vast majority of the Qing emperors’ seals have survived to this day. Created in various types and in complete sets, the seals shed important light on the personalities, interests, and cultural sophistication of the Qing emperors and provide invaluable material for research into Qing court history. Among them, the Qianlong Emperor’s seals are the most representative. They suggest several noteworthy phenomena. First, inscriptions on the imperial seals draw from an extremely wide range of sources. Some refer or allude to Confucian classics or are quotations from famous works of prose or poetry. More notably, many inscriptions originate in Qianlong’s own prose and poetry. As a case in point, the present tianhuang seal is inscribed with the line Jixi you yuxiang ('Fragrance lingers among the desks and mats'), drawn from a poem composed by Qianlong himself.

The seal is carved from Shoushan tianhuang stone, with a finial finely in the form of as a book and a scroll. Carved in relief, the seal text consists of the five characters Jixi you yuxiang. The seal measures 2.2 cm in length and 1.2 cm in width on its face and 4.2 cm in overall height. In material, dimensions, and calligraphic rendition and composition of the text, it matches exactly the records in the Qing court catalogues of imperial seals Qianlong baosou, Jiaqing baosou, and Daoguang baosou, and can be ascertained as an authentic imperial seal used personally by the Qianlong Emperor. Below, I summarise the historical information available about the seal to help the interested reader appreciate it further.

First, the seal text and its source reflect the basic characteristics of Qianlong imperial seals.

As is widely known, the Qianlong Emperor was highly cultivated and had a lifelong passion for composing prose and poetry. Poems attributed to him number over 40,000. Compared to extant classic poetry of the Tang dynasty, Qianlong’s poems have no lack of brilliant and memorable lines, and provided a ready and abundant source of inscriptions for his imperial seals. Indeed, the frequency with which Qianlong had his own poems inscribed on his seals was unprecedented. According to Qianlong baosou, “The twenty-six seals after ‘shuiyue liang chengming’ are all inscribed with lines from the emperor’s poems.” Inscribed on small seals, these lines evoke poetic imagery and are charged with profound metaphorical meaning. They reflect the cultivated tranquillity of Qianlong’s inner world. By having his own poems inscribed on his seals, Qianlong probably also expressed his pride and self-regard. The present Jixi you yuxiang seal is one of the twenty-six seals mentioned in Qianlong baosou. The text originated in the poem entitled “White Deer Grotto” that Qianlong had composed when he was a prince:

“Centuries after Li Bo built his hut, Ziyang unfurled his curtains [i.e. established his academy]. Observing the nation’s affairs was his destiny, and his moral virtue illuminated his writings. Penetrating the principles of moral cultivation, he conducted himself with ease in the ritual hall. Today his legacy is preserved in the Deer Grotto, where a fragrance lingers among the desks and mats.” This poem is recorded in fascicle 23 of Qianlong’s poetry anthology Leshantang quanji dingben. From context it can be determined that the emperor composed the poem in 1729, when he was still Prince Hongli and aged 19. Here Hongli not only introduces the history of White Deer Grotto, but also appraises the intellectual contributions of Zhu Xi, the great synthesiser of Confucian philosophy also known as Master Ziyang. The final couplet expresses Qianlong’s respect and admiration for this Song-dynasty philosopher. It was natural for him to select this poem and especially its last line, which contains an elegant and evocative image, to be inscribed on one of his seals. But why did Qianlong write a poem on White Deer Grotto in the first place?

White Deer Grotto is located on the foothills of Wulao Peak of Mount Lu in Jiangxi. During the Zhenyuan period of the Tang dynasty, Li Bo and his older brother Li She lived there as recluses. Li Bo kept a white deer as a companion and was thus known as Master White Deer. After becoming the governor of Jiangzhou, he built a terrace at the site of his reclusion, had streams redirected towards it, and had flowers planted around it. He named this site White Deer Grotto. During the Shengyuan period of the Southern Tang dynasty, a college was constructed at this site, and in the fifth year of the Xianping period of the Song dynasty, an academy was established there. The academy was later abandoned. During the Southern Song dynasty, the Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi, while serving as the governor of Nankangjun, rebuilt the academy, formalised its principles and pedagogical rules, and lectured there in person. He also successfully petitioned the emperor to bestow a calligraphic plaque upon the academy, greatly enhancing its reputation. For centuries afterwards, the White Deer Grotto Academy would remain an important site of culture and higher learning. Qianlong never visited White Deer Grotto personally, but he knew its history. According to his own recollection, “I started reading at age nine and writing essays at age fourteen.” Throughout his life, he perused the various classics of literature and philology and discussed them in depth in his own writing. We may reasonably surmise that Qianlong’s early education in the Confucian classics instilled in him a clear understanding of Zhu Xi’s thought and the history of White Deer Grotto. His poem on the site suggests a personal connection with Zhu Xi’s thought.

Another piece of evidence is a jade sculpture depicting the White Deer Grotto in the Palace Museum collection. One of its faces is carved with a grotto surrounded by hills. Above the grotto is a plaque that reads “White Deer Grotto.” Another face is carved with mountains and rocks, bridges, streams, a white deer carrying lingzhi fungus, and a young boy. A cartouche amongst the hills bears an inscription of Qianlong’s aforementioned poem on the White Deer Grotto. Like the present imperial seal, this sculpture is an example of court art inspired by Qianlong’s poetry.

The present tianhuang seal is notable also for its frequent use by the Qianlong Emperor.

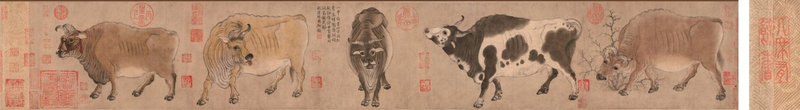

The first, second, and third compilations of Shiqu baoji and Midian zhulin – catalogues of painting and calligraphy in the Qing imperial collection – together record over 150 works impressed with this seal. Doubtlessly there were others not recorded in the catalogues. In other words, the Qianlong Emperor impressed this seal extremely frequently. In general, the seal was used in the following scenarios. In the first scenario, it was impressed as a leading seal (yinshou zhang) on Qianlong’s own calligraphy and calligraphic colophons. For example, Dong Bangda’s scroll painting A Broken Bridge and Remnants of Snow, now preserved in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, comes with a poem, separately mounted above the painting proper, on the subject composed and brushed by Qianlong. This poem is preceded by an impression of the present seal. In the second scenario, it was also used an ending seal (yajiao zhang) on Qianlong’s calligraphy and calligraphic colophons, either on its own or together with other small seals. The third compilation of Shiqu baoji records an Album of Flower Paintings by Qian Weicheng. Each of its twelfth leaves contains an inscription by Qianlong dated to 1771, and the inscription on the fifth leaf, which depicts roses, is followed by an impression of the present seal. The second compilation of the Shiqu baoji also records Two Albums of Scenes of Jiangdong by Dong Gao. The second album depicts ten scenes of Xixia in colour, and the fifth leaf, depicting “A Rock Split by Heaven,” bears a poem inscribed by Qianlong in 1780, after he saw experienced this scene in person during his Southern Tour. The poem is again followed by an impression of the present seal. These are examples of the present seal used independently as an ending seal. By contrast, Imperially Inscribed Album of Cotton Cultivation, now in Taipei, contains one leaf with a poem impressed at the top with the present seal and at the bottom with a seal reading Luozhi yunyan. Album of Thirty-Six Scenes of Bishu Shanzhuang by Zhang Zongcang, also in Taipei, contains one leaf with Qianlong’s poem on “Winding Streams Amidst Fragrant Lotuses,” again impressed at the top with the present seal and at the bottom with a seal reading Biduan zaohua. These are examples of the present seal used as an ending seal together with other small seals. The third scenario involves small-scaled paintings and calligraphy by Qianlong. In such cases, the seal impression has no fixed location and may appear in any suitable blank space. The catalogues describe such impressions as “impressed in various locations in the album” or “scroll.” The third compilation of Shiqu baoji records several small albums brushed by Qianlong, such as Sketches of the Four Friends, in which the present seal appears. In the fourth scenario, the seal was used as a “seam-riding seal” (qifeng zhang) – that is, across the seam between two separate pieces of paper or silk mounted together – very common in paintings and calligraphy in the court collection of the Qianlong period, such as Zhang Zhao’s calligraphic rendition of Lyric on the Stone Drum by Han Yu (fig. 1), sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong on 7th October, 2010, lot 2104 and recorded in Shiqu baoji. This work consists of two pieces of paper mounted together, and the seam between them is impressed with the present seal. The present seal, along with other small-scale imperial seals, can also be seen along the seams on other paintings and works of calligraphy that were remounted at the Qianlong court, either between silk borders or between the work proper and a silk border. The present seal, for example, is impressed along the seams of the front silk borders of Sui dynasty painter Zhan Ziqian’s Spring Excursion (fig. 2), and along the seams of the rear silk borders of Tang dynasty painter Han Huang’s Five Oxen (fig. 3). Straddling various sections of a work, these seam-riding seal impressions, if misaligned, clearly reveal remountings and damage and other forms of loss of integrity. It is possible that the Qing court used seam-riding seal impressions to ensure the completeness and permanence of the original mountings of its treasures. Qing records refer to such use of seals as jiancang baoxi ('seal of connoisseurship and collection'), and the present tianhuang seal was put to this use often.

Fig.1. Zhang Zhao (1691-1745), Lyric on the Stone Drum by Han Yu, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period, handscroll, ink on paper. Sotheby's Hong Kong, 9th October 2012.

Fig.2. Zhan Ziqian, Spring Excursion, Sui dynasty, handscroll, ink and colours on silk © Palace Museum, Beijing

Fig. 3. Han Huang, Five Oxen, Tang dynasty, ink and colours on silk © Palace Museum, Beijing

In practice, the Qianlong Emperor’s small-scaled imperial seals were used in a wide variety of ways. They were impressed not only on the paintings and calligraphy by Qianlong’s own hand and on works by historical personages and Qing court ministers recorded in Shiqu baoji and Midian zhulin, but also on painted catalogues of objects in Qianlong’s imperial collection. An impression of the present seal can be found, for example, at the top right corner of the verbal description on a leaf depicting a Song-dynasty dingyao lotus cup in Yanzhi liuguang, a painted catalogue of archaic porcelain, and at the bottom right corner of the image on a leaf depicting Zhoulü ge in Guanxiang zairong, a painted catalogue of archaic bronzes. Both catalogues are now at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. Furthermore, Qianlong also impressed the present seal on his everyday writings and on his own exercises in painting and calligraphy. For example, he impressed it at the end of his colophon to the Album of Heart Sutra on Bodhi Leaves with Inscriptions by His Majesty’s Hand, dated to 1768 and in the Palace Museum collection, as a collector’s seal. Another example is a fan with a jade handle that Qianlong had made in honour of the Empress Dowager in 1769. On one side is his calligraphic rendition of poems composed at the sight of lotuses. On the other side is his painting of orchids and rocks, on which he again impressed the present seal.

Lastly, the choice of tianhuang stone and the sculpting of the top finial reflect the aesthetic refinement of Qianlong’s seals.

In Qianlong baosou, Jiaqing baosou, and Daoguang baosou, the present seal is recorded as having been carved from dongshi ('grotto stone'), a general term that the Qing court used to refer to stones with a warm and translucent character. These include stones nowadays considered to be of the highest quality for seals – Shoushan tianhuang, furong, and Qingtian dongshi. With an even yellow tone resembling steamed maize, the present seal has a lucid and warmth luminescence and a fine and dense texture, with the highly appealing appearance typical of Shoushan tianhuang. Tianhuang is quarried from the shores of Shoushan Stream in Shoushan Village in Fuzhou, Fujian. Considered the finest stone from Shoushan, tianhuang is known as “the king of stones.” Some of Qianlong’s small-scaled imperial seals were made from tianhuang, and the present seal is consistent with the corresponding records in all three of the Baosou catalogues. The present small seal has a regular and symmetrical form. The finial is finely carved into the form of a book and a scroll tied together with a ribbon. The brocade pattern on the book and scroll and the soft texture of the ribbon demonstrate sophisticated artistry. Moreover, the finial appropriately mirrors the meaning of the inscription. Despite its small dimensions, the present seal is thoughtfully designed to achieve a delicate balance between detail and overall form and between different textures. Displaying superb artistry in composition and carving, it embodies the aesthetic refinement of Qianlong imperial seals.

Sotheby's. Important Chinese Art including Imperial Jades from the De An Tang Collection, Hong Kong, 13 October 2021

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_b8573a_telechargement-15.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240423%2Fob_af8bb4_telechargement-6.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240423%2Fob_b6c4a6_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_65a1d8_telechargement-31.jpg)