'Silent Poetry. Delicate paintings from the Southern Song dynasty' at National Palace Museum, Taipei

TAIPEI - Although literature and painting are two different modes of artistic expression, during the Southern Song dynasty, the surfaces of fans, albums, and small paintings were graced with no small number of paintings where "poetic sentiments merged with painted imagery." These richly poetic, finely-painted, small-sized artworks are broadly referred to as "delicate paintings" in this exhibit. The creation of artworks where painting and poetry blend into one another can be traced back to Su Shi (1037-1101) and other Northern Song dynasty literati, who believed that paintings are "silent poetry" and that poems are "formless paintings" or "paintings made from sound." Their stance stirred up a tsunami of artistic responses, and moreover, Northern Song dynasty emperor Huizong (1082-1135) enthusiastically supported the inscription of poetry atop paintings, further leading court painters to put the ideal of "poetry and painting merged as one" into practice.

The works on display in this exhibition fall into five sections: "Poems in the Emperor's Own Hand," "Small Landscapes: Ease and Repose in the Empty Wilderness," "The Pure Sounds of Mountains and Rivers," "The Poetics of Palace Gardens," and "The Joys of Floriculture." The first section, "Poems in the Emperor's Own Hand," draws attention to the importance Southern Song dynasty emperors placed upon artistic refinement, their calligraphic talents, and their intimate familiarity with well-known poetic and lyric writings. Emperors were actively involved in the creation of poetry and paintings, and their calligraphic inscriptions of verse can be found on the works of court painters. The second section, "Small Landscapes: Ease and Repose in the Empty Wilderness," aims at how many Southern Song dynasty delicate paintings used misty, sparse landscapes to create poetic ambience—a characteristic that in fact evolved from Northern Song dynasty "small landscape" painting.

Section three, "The Pure Sounds of Mountains and Rivers," guides visitors towards the profundities of landscape painting appreciation. During the Southern Song dynasty, depictions of the West Lake in Hangzhou and other scenery in the region south of the Yangtze River held primacy in landscape painting, but in subtle ways, the pervasive influence of the artistry of the Northern Song dynasty series of paintings "Eight Views of Xiaoxiang" can be detected in these works. The small-sized landscapes in this exhibit include scenes from the four seasons, ranging from dawn to dusk, creating the poetic sense of enjoying peace and quiet in a secluded slice of nature. This section displays two contrasting works, "Perched atop Boulders, Gazing upon Clouds" and "Dragging a Staff Beneath Pines," in order to explore how the ethos of "silent poetry" and "paintings made from sound" from art criticism influenced Southern Song painting.

The fourth section, "The Poetics of Palace Gardens," highlights the overlap between the imagery found in poetry and ci lyrics and Southern Song dynasty palace garden landscapes. Members of the imperial clan employed paintings that recreated poetic imagery to express the romantic and aesthetic sentiments. The fifth and final section, "The Joys of Floriculture," reflects the ways in which Southern Song dynasty paintings of flowers and plants are artistically interwoven with the charms of flower appreciation and poetic odes to flowers. We hope that visitors to this exhibit will enjoy themselves as they see the ways in which painting and poetry merged within the "delicate painting" of the Southern Song dynasty.

Poems in the Emperor's Own Hand

The Song dynasty was a period of governance through literacy, a time when importance was laid upon emperors' learnedness in fine arts and letters, including poetry, prose, and calligraphy. For generation after generation during the Southern Song dynasty, nearly every member of the imperial household was a capable calligrapher, and some were virtuosos. The emperors were deeply familiar the poetry, ci lyrics, poetic essays, and songs of past literary giants. They not only transcribed excerpts of these writings as gifts for their ministers, but also brushed them calligraphically atop paintings. In so doing, the imperial clan actively guided the artistic merger of poetry and painting.

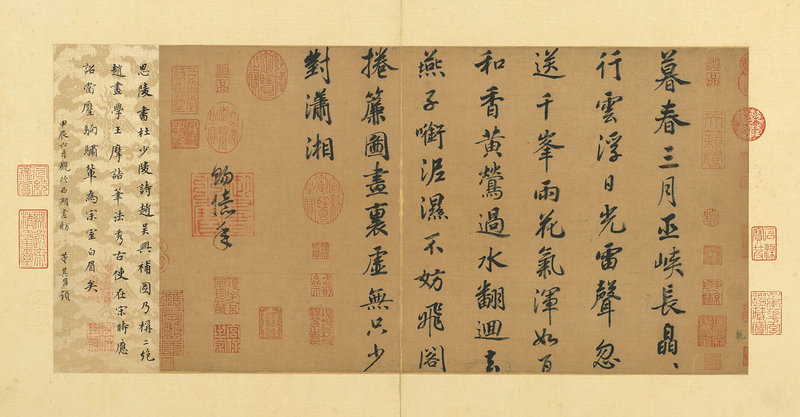

Poem in Seven Character Regulated Verse, Emperor Gaozong, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

As the Song dynasty was a period of governance through literacy, great importance was laid upon emperors' learnedness in fine arts and literature, including calligraphy. Gaozong (1107-1187), the first Southern Song dynasty emperor, was born in Zhuojun as Zhao Gou; he had the style name Deji. The last two emperors of the Northern Song dynasty, Huizong and Qinzong, were captured by the rival Jin dynasty; at this time Zhao Gou, then a prince, ascended to the throne.

Waking Up Next to a Rustic Window, Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

In this painting, a gentle breeze skims over the water's surface, willow trees greeting the wind with swaying branches. Atop the skiff moored beside the shore, a white-clad fisherman who has just risen from slumber stretches his limbs while looking out into the endless watery expanse, filling the scene with languorous contentment. The painting itself is unsigned, but it bears a transcription of "The Fisherman's Ode," a lyric poem by the Southern Song dynasty's first emperor, Gaozong 1107-1187). The poem was transcribed by Xiaozong (1107-1194), the second Southern Song dynasty emperor.

The fisherman theme seen in paintings such as this one usually alludes to the idealized life of a "hermit fishmonger." In ancient China, emperors were the most respected figures in the nation, yet they often pined for the worry-free lives of fishermen. Paintings devoted to this theme intimate pursuit of a state of mind marked by simplicity, serenity, languidness, and contentment. Poetry was combined with painting to help convey these sentiments. History records that the Southern Tang dynasty's final ruler, Li Yu (937-978), made an inscription upon a painting entitled "A Fisherman on the River in Spring." Clearly, in inscribing "The Fisherman's Ode" upon this painting, emperor Xiaozong was continuing a long tradition.

A Spring Walk on a Mountain Path, Ma Yuan, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

In the foreground, an elegant scholar wearing white robes and a headpiece of sheer black muslin slowly strolls along a path lined by flowers and willows. Near the lower left edge of the frame can be found a signature reading "Ma Yuan," the name of a court painter who was active during the reigns of Southern Song dynasty emperors Guangzong (r. 1190-1194) and Ningzong (r. 1194-1224). The poetry in the upper right corner reads "Wildflowers brushing my sleeves dance all by themselves, distant birds flee as I approach, not making a peep." The style of the calligraphy suggests that it was brushed by Ninzong, while the poetry is a single couplet taken from Northern Song dynasty scholar Cheng Hao's "Spring Day Serendipities." Cheng's poem describes tranquil wildflowers in a natural setting; a scholar brushing past them sets the flowers into motion, and causes the black-naped orioles on the willow branches to abscond in flight. The painting's layout creates exquisite reciprocity between its elements. Its focus is centered on the foreground, with the middle distances depicted with mysterious obscurity, and the far distance comprised of a few peaks wispily brushed in the upper left. The scholar's gaze extends into the world's empty vastness, naturally coaxing viewers' eyes towards the poetic thoughts that inspired this work, which were written by the emperor's hand. Brush and ink were used in this work in an utterly sublime manner.

Small Landscapes: Ease and Repose in the Empty Wilderness

Painters of small scale, poetic landscapes during the Southern Song dynasty excelled at using their brushes to create misty, indistinct ambience. This mode of artistic expression was a transformation of "small scenes" painting inherited from the Northern Song dynasty. During the Northern Song period, arts critics held that the "small scenes" works of the renowned Five Dynasties landscape painter Li Cheng and the famous Buddhist monk Huichong were characterized by a sense of ease, repose, and spaciousness. The central subject matter of Huichong's "small scenes," which he painted during the Northern Song dynasty, was waterfowl on the shoals of river isles. He used level distance composition to create emotionally evocative spaces within which viewers could allow their thoughts the freedom to roam.

Ducks and Birds in a Frigid Forest, Attributed to Huichong, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

A native of Jianyang in Fujian province, the renowned Northern Song dynasty Buddhist monk Huichong (fl. ca. early 11th century) was a talented poet and painter—his poetry was esteemed by the great scholar Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072). This painting takes wild geese and herons as its subject matter, in a composition centered around the frigid shoals of a remote river isle. It is a scene that conveys the easy repose that can be found in vast, empty wildernesses. Huichong painted such "small landscapes" (xiaojing), which, in their time, were considered to be rich with poetic meaning. Although none of his actual paintings remain in the world, surviving contemporaneous artworks depicting waterfowl on small islets in misty expanses demonstrate how Huichong's "small landscapes" influenced other painters during and after the Northern Song dynasty. Being traditionally ascribed to Huichong, "Ducks and Birds in a Frigid Forest" is this genre's representative work.

Human Figures, Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

This painting depicts a scholar seated upon a tatami bed, seated in a position of ease, reciting poetry and enjoying the flower arrangement before him. He is surrounded by a desk laden with tomes, a woven bamboo stool, a zither, a game of Go, scrolls, a stove for boiling tea, flowerpots, wine, and delicacies—an accurate representation of the elegant curios to be found in the studies of Song dynasty literati, who widely appreciated items of timeworn elegance.

A small scroll hanging from the painted screen behind the scholar seems that it may very well be a portrait of the selfsame individual. Worthy of note is that the room-dividing screen behind the scholar is painted with a scene of waterfowl on the shoals of an islet—this is a painting of the "small landscape" genre fashionable in the day. The upper portions of this piece carry seals reading "Xuanhe" and "Zhenghe," which indicate that it was part of Song dynasty emperor Huizong's collection, as well as the qian trigram and "Shaoxing," which show that it was also held in Emperor Gaozong's collection. These seals provide insight into the continuation of artistic trends during the period of transition between the Northern and Southern Song dynasties.

Yellow Oranges and Green Mandarins, Attributed to Zhao Lingrang, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

The calligraphy and painting seen here were both originally affixed to circular fans, and were later mounted in album format. The calligraphy is Song dynasty emperor Gaozong's transcription of a poem written by the Northern Song dynasty scholar-official Su Shi (1037-1101). Su wrote this piece, entitled "A Poem for Liu Jingwen," in the fifth year of the Yuanyou reign period under Emperor Zhezong (1090). The painting is a refined blue-and-green landscape depicting orange and mandarin groves along the undulating shores on both sides of a river. Between the banks can be seen wagtails and teals. The overall composition is suffused with a hint of misty forests and river wilds, merged with river-islets-and-waterfowl subject matter. This elaboration of Huichong's "small landscape" compositions (fl. ca. early 11th century) mirrors the accompanying lines of poetry, "Remember, of all the beautiful sights the seasons bring, none are better than early winter, when the oranges are yellow and the mandarins are green."

The original label on this album attributes the painting to Zhao Lingrang (style name Danian, fl. ca. 1070-1100), a northern Song dynasty painter who was a member of the imperial family. However, a close analysis of the style of painting indicates that it is most likely the work of an unnamed court painter from the early Southern Song dynasty.

The Pure Sounds of Mountains and Rivers

Capital of the Southern Song dynasty, the city of Hangzhou's most striking scenery was immortalized in "Ten Scenes Around the West Lake" and other small landscape paintings. The works, which were fused with depictions of the four seasons and scenery at dawn and dusk, are profoundly unique. This genre of painting was heavily influenced by artistic techniques descending from the Northern Song dynasty's "Eight Views of Xiaoxiang." In this section of the exhibit, a special space entitled "Silent Poems/Aural Paintings" shows two paintings—"Perched atop Boulders, Gazing upon Clouds" and "Dragging a Staff Beneath Pines"—next to one another. The contrast found in their pairing highlights a stance shared by Su Shi and many others during the Song dynasty, that painting is "silent poetry," and poetry is "formless painting" or "painting with sound."

Snowy Twilight by a Mountain Stream, Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

This painting's foreground depicts groves of trees growing streamside on uneven ground. Amid them, a traveler carrying a load makes his way, his head huddled against the cold. Also in the near ground can be seen structures with snow-covered eaves, the gate to the bamboo fence enclosing them left halfway open, with a murder of crows circling above. Across the stream, in the middle ground and half-obscured in the misty foothills, birds play in the water, creating a scene that is at once expansive and indistinct. In the far distance is a cluster of massifs under the clear skies following a snowfall, with a Buddhist temple tucked into a dense convergence of ridges and trees. The furthest mountain, which looks almost as though a paper cutout, stands unilluminated in the falling dusk. This painting's creator is unknown, but its style marks it as likely to be the work of an early Southern Song dynasty artist. One of the landscapes in Northern Song dynasty literati painter Song Di's (ca. 1015-1080) renowned series of paintings, "Eight Views of Xiaoxiang," is entitled "A Snowy Riverscape by Evening." The work on display here is an intentional continuation of the theme of snowy sunsets, but it integrates "small scene" subject matter, creating a remarkable sense of liveliness.

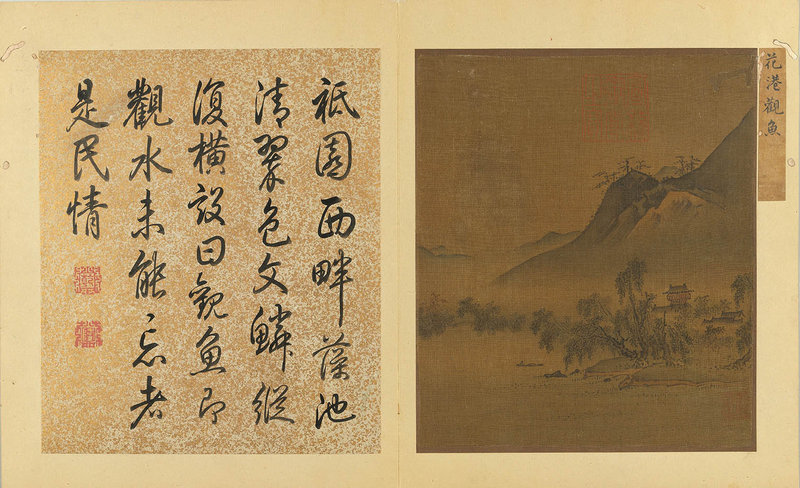

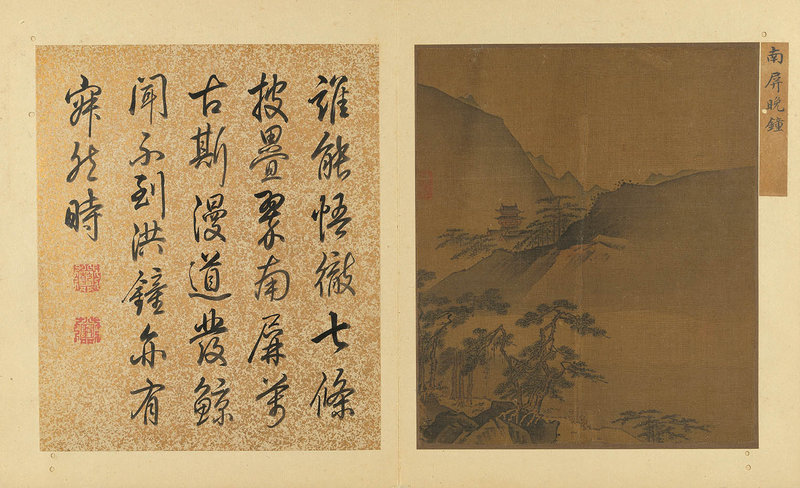

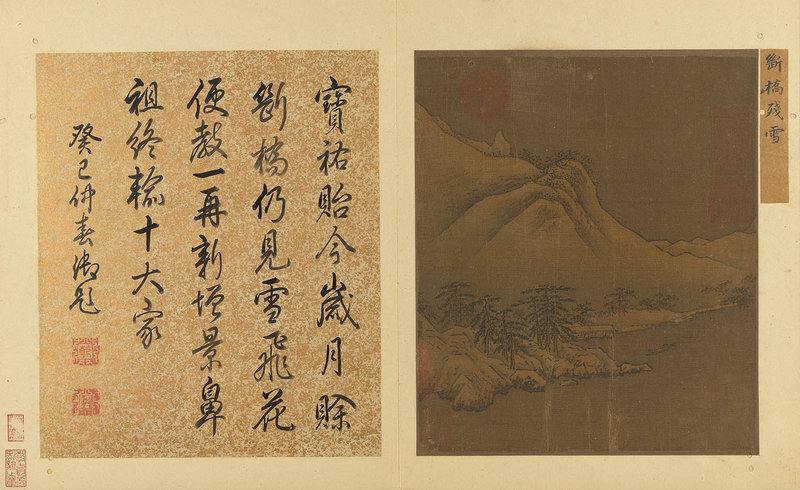

Ten Scenes Around the West Lake, Ye Xiaoyan, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

The lower left-hand corner of this album's tenth leaf is signed with two characters—"Xiaoyan." Ye Xiaoyan was a painter from Hangzhou who was active during the first half of the thirteenth century. His extant works are few in number, and records of his life are scarce. References to the "Ten Scenes Around the West Lake" subject, which became popular during the Southern Song dynasty, can be found in writings dating to the thirteenth century. The ten scenes included "Spring Dawn at Su Dongpo's Dyke," "Listening to Orioles Under Swaying Willows," "Gazing at the Fish of Flowery Cove," "Lotus-scented Breezes at the Winery," "Twin Peaks Piercing the Clouds," "Sunset Over Thunder Ridge Pagoda," "Three Ponds Imprinted with the Moon," "Placid Lake, Autumn Moon," "The Evening Bells of Nanping Hill," and "Vestiges of Snow at the Broken Bridge." Each painting corresponds to different scenery around the lake, portrayed in lucid and elegant style throughout the four seasons and at different times of day. The Northern Song dynasty album of paintings entitled "Eight Views of Xiaoxiang" originated a genre of paintings that depict famous, real-life locales both night and day at different times of year in order to the elicit poetic sentiments connected to each site. The genre evolved during the Southern Song dynasty, leading to landscape paintings richly imbued with the spirit of the city of Hangzhou.

Clear Skies After a Snowfall over a Placid Lake, Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

The recorded name for this unsigned work is "Clear Skies After a Snowfall over a Placid Lake." Composed in the "leaning to one corner" (bianjiao) manner, this painting is stylistically similar to the works of Southern Song dynasty painter Xia Gui (fl. 1180-ca. 1230). The "placid lake" of the title refers to the serene, mirror-like surface of the lake's water. Small-scale landscapes depicting expansive lakes were a common sight in Southern Song dynasty painting, and it is quite possible that this work was meant to portray the environs of the West Lake in the dynastic capital of Hangzhou. On the far shore are depicted low-hanging willow trees, a bamboo fence, and a snow-covered dwelling hidden in the woods. The painting illustrates the moments when a snowfall ceases and gives way to clear skies, creating the atmosphere of a tranquil redoubt surrounded by nature.

Perched atop Boulders, Gazing upon Clouds, Li Tang (ca. 1070-1150), Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

Li Tang (ca. 1070-1150) was a renowned painter who lived during the transition between the Northern and Southern Song dynasties. His "Wind in Pines Among Myriad Valleys," created during at the end of the Northern Song dynasty, portrays layer upon layer of densely packed mountains, painted with "axe-cut" texturing strokes and blue-and-green washes of varying shades applied to the mountains and boulders. The painting transports the viewer into a flourishing pine forest spanning a network of plunging valleys.

The painting displayed here is unsigned. It has traditionally been recognized as one of Li Tang's works, but it is in actuality a Southern Song dynasty work painted in his style. It depicts a pair of eremitic scholars whose peregrinations have taken them to the cusp of the wilds. Perched atop boulders, the two recluses look with pleasure upon the scene of roiling mists before them. From deep within the forest of twisting, verdant pines emanate the sounds of a gushing spring, as clouds surge skywards like steam before the scholars' eyes. Seated creekside, the gentlemen cool their feet in the flowing waters, their manner suggesting unsurpassable joy. Beholding this painting, one feels the pull of the imagery in a couplet in Tang dynasty poet Wang Wei's "Zhongnan Mountains Pied-à-terre." The couplet reads: "We stroll to where the waters meet their end, and sit to witness the moment when the clouds ascend."

Dragging a Staff Beneath Pines, Attributed to Xu Daoning, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

A signature reading "Daoning" can found on this painting's lower left, and it was previously labeled as the work of Northern Song dynasty painter Xu Daoning (ca. 11th century). However, the pine tree, bamboo, and human figure all show the influence Liu Songnian's (fl. late 12th century) painting style, indicating that it was actually created during the late Southern Song dynasty.

This painting depicts a scholar, staff in hand, following a narrow lakeside trail under the shade created by a deep green pine and verdant bamboo. His headdress and sash flutter softly in the wind as the scholar stands still to enjoy the sounds of the soughing pine. Paintings such as this one attempted to use visual art to convey the aural motif of "listening to pines" found in poetry and lyrics—to Southern Song dynasty painters, this subject matter presented no small challenge. Early on, during the Northern Song dynasty, Su Shi and others were devoted to the fusion of poetry, lyrics, and painting. They described paintings as "silent poetry" and poems either as "formless paintings" or "paintings made from sound." This train of thought further developed during the Southern Song dynasty, with the creation of "acoustic paintings."

The Poetics of Palace Gardens

Southern Song dynasty imperial palace gardens were places richly instilled with poeticism. The names of structures built on their grounds were chosen with a sense of literary nostalgia from lines of famous poetry, with the intent of creating an aesthetic mood of elegance and romanticism amid the gardens. The imperial family's activities within the palaces and gardens were also modeled in an attempt to recreate and experience the sentiments written down in poetry. The delicate paintings that have been passed down through history reveal both the ephemeral moments and eternal aspirations found in the meeting of sensibility and setting in imperial palace gardens.

The Lotus-scented Breezes of Taiye Pond, Feng Dayou, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

This unsigned painting was previously catalogued as the work of Feng Dayou (fl. 12th century), a native of Suzhou in Jiangsu province. Feng rose to the rank of case reviewer in the Court of Judicial Review; he used the sobriquet Yizhai.

This beautiful scene is filled with swaying lotus leaves interspersed with pink and white lotus flowers. The painting overflows with life, with swallows and butterflies dancing in the air above, and a raft of ducks languidly searching for food in the water below. The title, "The Lotus-scented Breezes of Taiye Pond," is a nod towards both the painting and the accompanying poetry. The poetry is Song dynasty emperor Gaozong's calligraphic rendition of Tang dynasty poet Wang Ya's (?-835) "Autumnal Thoughts." "Taiye" was the name of a pond in the palace of Emperor Wu of Han, which was recorded in "The Treatise on Religious Sacrificial Ceremonies" in The Records of the Grand Historian. Later, it came to mean any pond in an imperial palace garden. Records state that, during the Southern Song dynasty, Emperor Xiaozong had 10,000 pink and white lotuses planted in his pond in separate, sunken pots that could be removed and swapped for fresh plants to maintain the scenic beauty. The alternating pink and white lotus flowers in this painting reveal the aesthetics of Southern Song dynasty palace gardens.

A Candlelit Nighttime Excursion, Ma Lin (ca. 1180-after 1256), Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

A signature reading "Your servant, Ma Lin" appears on the lower right side of this painting. Ma Lin (ca. 1180-after 1256) was a court painter active during the reigns of Southern Song dynasty emperors Ningzong and Lizong.

This painting depicts a building modeled with graceful beauty. Its pointed, hexagonal roof with double layered eaves rises upwards, while ambulatories stretch in either direction. Its subject sits on a round-backed chair, reveling in the flowers and trees in the courtyard. Candleholders line the courtyard path, while a full moon high in the night sky shines down upon the indistinct nightscape. The scene is a painted rendition of the imagery found in Northern Song dynasty writer Su Shi's poem "Begonias," which contains the lines "My only worry is that deep in the night the flowers will drift to sleep, so I light these tall candles to shine on their pink petals." During the Southern Song dynasty, floriculture was very popular in the imperial gardens. Annals of the Qiandao and Chunyi Reign Periods records that Emperor Xiaozong's location for enjoying begonias in his private garden was called "Shimmering upon Rouge Pavilion," evidence that names for some sites in the imperial gardens were adapted from Su Shi's poetry. This piece illustrates the Southern Song emperor's romantic penchants for viewing begonias by night and chasing the imagery in Su Shi's stanzas.

Watching the Tidal Bore on a Moonlit Night, Li Song (fl. ca.1190-1264), Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

The city of Hangzhou, formerly the capital of the Southern Song dynasty, borders the Qiantang River. Watching the tidal bore surge up the river by night was a popular mid-autumn festival diversion in the Song period. The architecture of the two-story building portrayed in this painting is sumptuous. It has hip-and-gable roof with single eaves, and soars high over the riverside, while its viewing platform is connected to a winding ambulatory that abuts a courtyard embellished with miniature mountains built of stacked stones. The human figures within were originally painted using pigments from powdered clam shells, but unfortunately they have flaked away over time, leaving difficult to discern.

The calligraphy on this painting, transcribed from Su Shi's poem "Watching the Tidal Bore on the Fifteenth Day of the Eighth Lunar Month," was written by Empress Yang (1162-1233), consort of Emperor Ningzong (r. 1195-1224). Next to it is the imprint of a seal carved with the kun trigram, which represents earth and femininity. On the lower left the painting is signed, "Your servant, Li Song." Li Song was a court painter active from 1190 to 1264, during the reigns of emperors Guangzong, Ningzong, and Lizong, noted for his outstanding skill at painting architecture.

The Joys of Floriculture

During the Southern Song dynasty, viewing flowers, writing poetry about them, and engaging in floriculture were all very much in vogue. These pastimes were in fact all continuations of Northern Song dynasty royalty and literati's similar passion for poetically singing the praises of various flowers and plants. Painters, like poets, had the ability to portray the world and its objects in exquisite detail, and they too turned their brushes towards giving full expression to flowers' beauty and vitality.

Painting from Life of Poppy Flowers, Ai Xuan, Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

Ai Xuan was a native of Jinling (present day Nanjing). A talented painter of flowers, bamboo, birds, and mammals, his remaining works are exceedingly rare. This painting is a renders the bright, colorful glory of poppy flowers in full bloom in summertime. The stems and leaves were outlined with a fine brush, while the flowers were painted with powdered clamshell pigments and colored washes, a technique that gave them equal parts density and brightness.

The accompanying poetry was written by Empress Yang (1162-1233), consort of Emperor Ningzong (r. 1194-1224); it carries the imprint of a seal reading "Emperor's Calligraphy." The style of calligraphy is that of the empress's later years, when she shifted from writing delicate characters to those with ample, lustrous appearances. The term "Palace of Eternal Springtime" appears in the poem—it is a reference to a side hall in the palace of Northern Song dynasty emperor Zhenzong. During the Southern Song dynasty, Zhao Sheng recorded this palace hall's name in Important Affairs of Court and Country, adding that it was a place where magnificent feasts were held. This union of poetry and painting allows the splendor of poppy flowers to blossom before the viewer, accenting the auspicious settings enjoyed in imperial palaces. The color palette, which was chosen in accord with gongbi painting methods, yields poppy flowers as glorious as the sun.

Yellow Oranges and Green Mandarins, Lin Chun (fl. ca. 1174-1189), Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

Much as with flowers and certain plants, oranges and mandarins were an object of aesthetic appreciation in the Southern Song dynasty court. Zhou Mi's Remembrances of Wulin records that, on royal grounds, "oranges and mandarins could be enjoyed from the Gilded Pavilion at Lucid Swallow Palace." During the Southern Song dynasty, a trend of venerating literature dating to the Northern Song dynasty's Yuanyou reign period began under Emperor Gaozong, resulting in the poetry of Su Shi and his contemporaries rising in popularity and importance. A couplet from one of Su Shi's poems which reads, "remember, of all the beautiful sights the seasons bring, none are better than early winter, when the oranges are yellow and the mandarins are green," was especially relished during this period.

The left border of this painting is signed "Lin Chun" in regular script. Lin painted this small fan's surface by outlining branches laden with leaves and citrus fruit. The colored washes used to portray the oranges were further dotted with color, yielding gold-like patina, while the mandarins were rendered using washes of green ink with superb tonal variation. These advanced techniques for painting lifelike scenery deftly elicit the poetic sentiments in Su Shi's words.

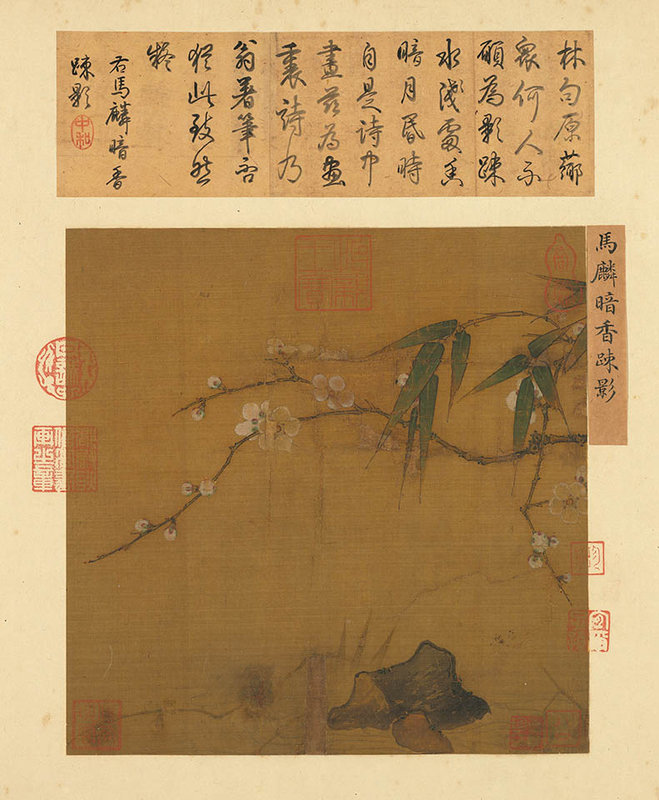

Subtle Scents, Diffuse Shadows, Ma Lin (ca. 1180-after 1256), Song dynasty (960-1279). © National Palace Museum.

This painting is unsigned, but it was previously catalogued as "‘Subtle Scents, Diffuse Shadows' by Ma Lin." It portrays white plum blossoms whose stems and calyxes were pigmented with malachite and carmine. This coloring matches the description of "green calyx plum blossoms" found in Fan Chengda's (1126-1193) Plum Taxonomy. Fan wrote, "in the Wu region there is another varietal, the stem and calyx of which are slightly green, and whose rims are of a pale purplish-red. It is most rare." This painting depicts the imagery found in a couplet by the Northern Song dynasty poet Lin Bu (968-1028), which reads, "Diffuse shadows crisscross the clear, shallow waters; subtle scents undulate beneath the twilight moon." The inclining branches of a plum tree can be seen mingling with leaves of bamboo. The composition moves diagonally from right to left, the angular turns of the plum branch painted with consummate elegance atop a featureless backdrop. In the reflection of the plum branch and bamboo leaves on the surface of the water below, the white flower buds and green stems and calyxes can be vaguely discerned. Refraining from painting the moon, but painting the shadows and reflections cast by the moonlight, the artist reached the apogee of refinement.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240315%2Fob_7bd30a_431977340-1633099410793405-26442445716.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F38%2F119589%2F129504991_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F47%2F86%2F119589%2F129060970_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F33%2F75%2F119589%2F129054916_o.jpg)