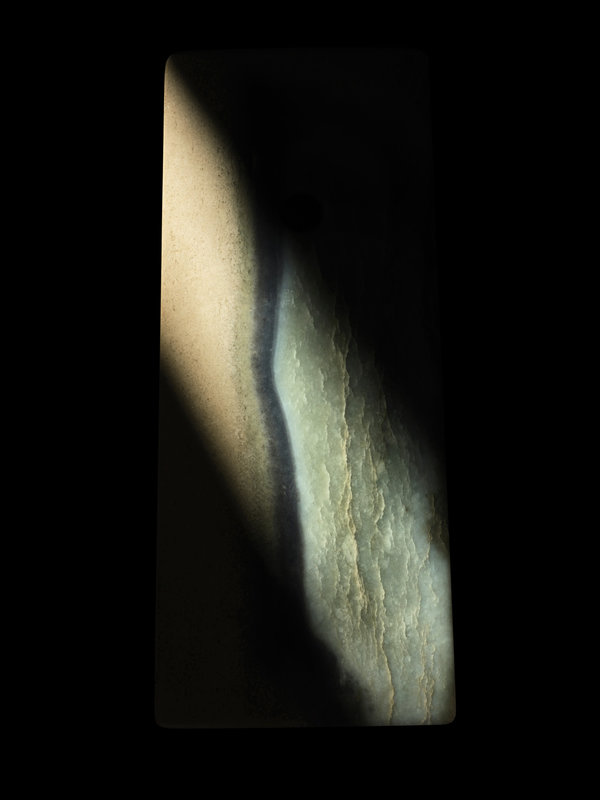

The Guennol archaic jade ceremonial axe (Yue), Neolithic period - Zhou dynasty

Lot 525. The Guennol archaic jade ceremonial axe (Yue), Neolithic period - Zhou dynasty. Length 4⅝ in., 11.7 cm. Lot Sold 1,016,000 USD (Estimate 400,000 - 600,000 USD). © 2023 Sotheby's

Property from the Collection of Robin Bradley Martin

Provenance: Sydney L. Moss, London, until February 1957.

Bluett & Sons Ltd., London, 26th April 1957.

Collection of Lord Cunliffe, The Rt. Hon. Rolf, 2nd Baron Cunliffe of Headley (1899-1963).

Bluett & Sons Ltd., London.

Collection of Count Dominique de Grunne.

Barry Sainsbury Oriental Art, London, 1977.

The Guennol Collection (collection of Alastair Bradley Martin and Edith Martin), until 1983, and thence by descent.

The present lot illustrated in Early Chinese Art, Bluett & Sons Ltd., London, 1973, cat. no. 57.

Literature: Amy G. Poster, 'Ceremonial Knife', The Guennol Collection, vol. II, New York, 1982, p. 83.

Minao Hayashi, Studies of Ancient Chinese Jades, Tokyo, 1991, p. 510, fig. 6-130.

Minao Hayashi, Yang Meili trans., Zhongguo guyu yanjiu [Studies of ancient Chinese jades], Taipei, 1997, p. 346, fig. 6-130.

Exhibited: Early Chinese Art, Bluett & Sons Ltd., London, 1973, cat. no. 57.

Brooklyn Museum, New York, 1977-2023 (on loan).Sotheby's. Important Chinese Art, New York, 22 March 2023

A Ceremonial Jade of Power: The Guennol Yue

his jade axe is exceptional for the richly varied colors of the stone and the simple yet powerful silhouette. The central striation, which has been incorporated in the design of this axe, runs almost snake-like through the middle, contrasting strikingly with the rigid shape. This masterwork of jade from ancient China has a timeless aesthetic that blurs the boundary of the past and present. It is an embodiment of the ingenuity and imagination of the ancient Chinese carvers, who attained near perfection in working with this precious material using only primitive tools. As the level of workmanship involved in the creation of jade objects was an indication of its owner's importance, it is likely that the present axe belonged to a powerful person who was in the position to command such a important piece.

There are two closely comparable jade blades known. One is preserved in the Fogg Museum, Cambridge (accession no. 1943.50.96) (fig. 1), donated by Grenville L. Winthrop in 1943, published on the Museum's website and in Max Loehr, Ancient Chinese Jades from the Grenville L. Winthrop Collection in the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, 1975, pl. 345; the second, from the Drummond Collection, is in the American Museum of Natural History, New York (acc. no. 70.3/ 3015), published in Minao Hayashi, Yang Meili trans., Zhongguo guyu yanjiu [Studies of ancient Chinese jades], Taipei, 1997, p. 317, fig. 6-68. Both the Winthrop and Drummond jades, although oriented horizontally in the form of a blade, bear a striking resemblance to the present axe in terms of the stone color and natural markings, indicating the possibility of these works originating from the same stone. Max Loehr attributed the Winthrop blade to possibly the Eastern Zhou dynasty. This attribution has been revised by the Fogg Museum on their website to the Shang dynasty. The Drummond blade has been attributed by Mino Hayashi to the Erligang period (c.1500 - c.1300 BC).

fig. 1. Trapezoidal Knife-Shaped Jade Tablet, Harvard Art Museums / Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Bequest Of Grenville L. Winthrop. Photo © President And Fellows Of Harvard College, 1943.50.96

The present jade axe is named yue 鉞 in Chinese. While related jades of this form are collectively termed 'axe' in English, they have several different names in Chinese, including fu 斧, chan 鏟, yue, and qi 戚. Yu Yanjiao and Fang Gang provided a clarification in their book, Zhongguo yuqi tongshi. Xiashangjuan [The history of Chinese jade. Xia and Shang dynasties], Shenzhen, 2014, p. 160, where the authors suggests fu, chan, yue, and qi all originated from late Neolithic period stone prototypes of the Longshan culture. Jade fu and chan are both functional items, whereas jade yue and qi are ceremonial weapons. Ceremonial jades of a trapezoidal form with either a straight or curved edge should be named yue.

Jade yue of this type have been produced for a long period of time in China, from as early as the Neolithic period to the Zhou dynasty. As a ceremonial weapon, jade yue symbolized power and authority in ancient Chinese culture. According to Shiji. Yinbenji [Records of the Grand Historian. Annals of Yin], Tang 湯, the founder of the Shang dynasty used yue to defeat Jie 桀, the notorious last king of the Xia dynasty. Zhoubenji [Annals of Zhou] further records that King Wu of Zhou 周武王 decapitated Di Xin 帝辛, the last king of the Shang dynasty, with huang (yellow) yue and xuan (mysterious) yue. Jade yue were originally attached to a wood pole decorated with a matching ferrule, dui 鐓 and a crown, mao 瑁. See Teng Shu-p'ing ed., Gugong Yuqi jingxuan quanji. Yuzhiling / Select Jades in the National Palace Museum. The Spirit of Jade, vol. 1, Taipei, 2019, p. 251, fig. 193, for a diagram showing how these parts were originally assembled.

As a symbol of status and prestige, jade yue are rare, as Jessica Rawson states, "...they were rarely made of jade. Flat axes were of a better shape to show off the stone to its advantage and therefore display power and authority" (Chinese Jade from the Neolithic to the Qing, London, 1995, p. 169). Archeological findings indicate jade yue can be found in several Neolithic cultures, including Longshan, Qijia, and Shimao (see op. cit., 2019, p. 62). Compare a Longshan culture jade yue of a smaller size, excavated from tomb no. 203 at Xizhufeng site, Linqu, Shandong province, now in the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing, published in Gu Fang, Zhongguo chutu Yuqi quanji / The Complete Collection of Jades Unearthed in China, vol. 4, Beijing, 2005, pl. 22; and another of a related stone color, in the British Museum, London (accession no. 1937,0416.26), attributed to possibly from northwestern Neolithic cultures, illustrated on the Museum's website and in op. cit., 1995, p. 177, fig. 1.

Even fewer jade yue of this quality from the Shang and Zhou dynasties have been recorded. See a middle Shang dynasty jade yue of a smaller size, excavated in Xinzheng county, Henan province, published in Yang Boda, ed., Zhongguo yuqi quanji [The complete collection of Chinese jade], vol. 1, Shijiazhuang, 2005, p. 134, pl. 24; and another with a curved edge and a short, protruding shaft, excavated from the Fuhao Tomb in Yinxu, published in The Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, ed., Yinxu fuhao mu / Tomb of Lady Hao at Yinxu in Anyang, Beijing, 1980, pl. CXVII.

For Zhou dynasty jade yue, see a slightly smaller example of a similar stone, from the Bahr Collection, now in the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, illustrated in Berthold Laufer, Archaic Chinese Jades Collected in China by A. W. Bahr Now in Field Museum of Natural History Chicago, New York, 1927, pl. IV; another, discovered from tomb no. 5 at the burial site of Yongningpu, Hongtong county, Shanxi province, now preserved in the Shanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Taiyuan, attributed to the Western Zhou dynasty, published in Gu Fang, op. cit., vol. 3, pl. 72; and a third of a similar size, excavated in Cuimu town, Fengxiang county, Shaanxi province in 1961, now in the Shaanxi History Museum, Xi'an, attributed to early Western Zhou dynasty, illustrated in Chen Zhida and Fang Guojin, ed., Zhongguo yuqi quanji [The complete collection of Chinese jades], vol. 2, Shijiazhuang, 2006, pl. 197.

While it is nearly impossible to trace the geographical origins of the Guennol jade yue, this stone material, characterized by the distinct variegated colorations with dark markings, can be compared to some of the ritual jades discovered in Gansu province. A group of such examples from the Qijia culture is published in Gu Fang, op. cit., vol. 15, including a jade bi disc, excavated from Huangniangniangtai, Wuwei city, now in the Gansu Provincial Museum, Lanzhou, pl. 1; another, discovered from Houliugou village, Jingning, currently preserved in the Jingning Museum, pl. 4; and a jade cong, unearthed in Lintao, now in the Dingxi Museum, Dingxi, pl. 31.

Sotheby's. Important Chinese Art, New York, 22 March 2023

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F12%2F01%2F119589%2F127239311_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F44%2F63%2F119589%2F127209167_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F18%2F79%2F119589%2F122531217_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F66%2F86%2F119589%2F121530778_o.jpg)