Le Grand Mazarin. An Historic Coloured Diamond

Lot 600. Le Grand Mazarin. An Historic Coloured Diamond. Estimate On Request. Price realised CHF 14,375,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017

The light pink old mine brilliant-cut diamond, weighing approximately 19.07 carats.

Accompanied by report no. 5182785154 dated 4 October 2017 from the GIA Gemological Institute of America stating that the diamond is Light Pink colour, VS2 clarity, and Diamond Type Classification letter stating that the diamond has been determined to be Type IIa.

Provenance: Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661)

Louis XIV, King of France (1638-1715)

Louis XV, King of France (1710-1774)

Louis XVI, King of France (1754-1793)

Napoleon I, Emperor of the French (1769-1821)

Marie-Louise of Austria, Empress of the French (1791-1847)

Louis XVIII, King of France (1755-1824)

Charles X, King of France (1757-1836)

Napoleon III, Emperor of the French (1808-1873)

Eugenie de Montijo, Empress of the French (1826-1920)

Frédéric Boucheron (1830-1902)

Baron von Derwies

Private collection.

Note: To tell the story of the Grand Mazarin diamond is to delve deep into the History of France. It is also to tell the story of more than three-and-ahalf centuries of enthralling stories involving a legendary cardinal, four kings, four queens, two emperors, two empresses, a spectacular jewel robbery, a notorious auction and the greatest jewellers of France.

But like all stories that begin with ‘once upon a time...”, the story of this exceptional stone also has a starting point. Winding the hands of the clock back more than 350 years inevitably leaves room for doubt, but if there is one single fact that is completely incontrovertible, it is that the Grand Mazarin originated in the legendary Golconda diamond mines.

Long before diamonds were discovered and mined in Brazil and South Africa, India was the ‘land of diamonds’. The Golconda diamond

mines in the south of the Deccan plateau are renowned for having produced the most beautiful diamonds in the world.

As well as having exceptional clarity and incomparable transparency, Golconda diamonds also have a distinctively special aura that sets them apart from all other stones and yet defies description in words. So it is no coincidence that the most exceptional diamonds in history, including the Koh-i-Noor, the Regent Diamond and the Wittelsbach-Graff Diamond, also came from these mines.

The Grand Mazarin is no exception, and its ‘water-clear’ crystallinity is the ultimate proof of that.

Map of the Bay of Bengal, 1712 © Bibliothèque Nationale de France

The official history begins with the person who lent his famous name to this diamond: Cardinal Mazarin. Jules Mazarini, known as Mazarin (1602-1661), was an Italian-born diplomat who began his career in the service of the Pope. A few years later, he emigrated to France and joined the private inner circle of King Louis XIII, and later that of his son and successor Louis XIV.

Appointed as Chief Minister of France in 1642, his interests were not confined solely to politics. He had a passion for precious stones, and particularly diamonds. Having amassed a fortune over the course of his career, he brought together a collection of eighteen exceptional diamonds towards the end of his life; these were the most beautiful jewels in Europe purchased from the royal families of Europe or sourced from his favoured jeweller Lescot, who was commissioned to secure the very best stones.

Portrait of Cardinal Jules Mazarin, by Pierre Mignard, 1658-1660 © Musée Condé, Chantilly / Bridgeman Images.

In his will of 6 May 1661, drafted just before his death, he bequeathed this fabulous collection to his Majesty King Louis XIV, donating his diamonds to the Crown of France.

Authentic copy of Cardinal Mazarin’s will © Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Of the eighteen diamonds, only three were honoured with specific names: the Sancy Diamond, the Mirror of Portugal and the Grand Mazarin. The last of these three was the largest of the eight ‘square cut’ Mazarin diamonds; its size was unusual at the time, making it a stone for which the Cardinal had a particularly strong affection.

The diamonds from this exceptional collection became part of the French Crown jewels, and quickly established themselves as some of the king’s favourite gems. They were to remain the favourite stones of the French royal family for more than 200 years.

When the eighteen Mazarin diamonds passed into the possession of King Louis XIV, he was only 23 years old and had married the Spanish Infanta Maria Theresa of Austria just one year earlier.

She is very likely to have been the first person to wear the Grand Mazarin. In the famous portrait by Charles Beaubrun of her with her son, the Grand Dauphin of France (see page 13), she wears fabulous jewellery of pearls and diamonds. The impressive aigrette securing the feathers to her hat is set with five large pear-shaped pearls and two diamonds of very particular shapes. The shapes of these diamonds inevitably evoke two of the Mazarin diamonds that had recently passed into the ownership of the French royal family: the Mirror of Portugal and the Grand Mazarin.

B. Morel, The French Crown Jewels, 1988. Rendering by Bernard Morel.

As was the fashion, the most beautiful diamonds owned by the French royal family never stayed very long in the same setting, and were set and reset as and when jewels were required for royal events.

Being a great lover of diamonds himself, Louis XIV added the Grand Mazarin to his fabulous chain of diamonds after the death of Maria Theresa. Having amassed a large number of diamonds as new additions to the French Crown jewels, Louis XIV commanded a new inventory of his jewels in 1691. His impressive chain of diamonds figures prominently in this inventory, and each diamond is described with a very high degree of precision. This chain, similar in appearance to a necklace, was probably a chain in which individual stone settings were removable to allow the king to wear the diamonds together or separately as accessories to his robes. Which is why the precise description of the chain names the diamonds in descending order of size.

The Grand Mazarin is described at number five in the list: ‘A large, thick diamond, donated to the Crown by M. Le Cardinal Mazarin, known as LE GRAND MAZARIN, square cut, of very great limpidity, slightly vinous, clear, missing a little of the stone at its four corners, weighing 21 carats, estimated at 75 thousand livres.’

One of the most interesting items of information given here is the very particular description of the colour of the stone: ‘slightly vinous’ is a little-used but strong indication that marvellously expresses the slight rose tint of the diamond.

The diamond would remain on the chain for many years, although it was sometimes used in temporary settings to create jewellery for

special occasions. The exceptionally long 72-year reign of Louis XIV would leave its indelible mark on French history. The Château of Versailles, whose construction he supervised, has left to posterity the image of a king enamoured by grandeur and well deserving of his epithet The Sun King.

Queen Marie Thérèse and her son the Dauphin of France, by Charles Beaubrun, 1663-1666.

Louis XIV, King of France, in royal costume, by Hyacinthe Rigaud, 1701 © Musée du Louvre / Bridgeman Images.

When Louis XIV died in 1715, his successor and great-grandson was only five years old. Louis XV was crowned King of France in Reims Cathedral seven years later in October 1722.

Until that time, the Kings of France were crowned with the gold ‘Charlemagne’ crown set with precious stones. For the coronation of Louis XV, the Charlemagne Crown was accompanied by a personal crown crafted in silver-gilt and set with the most beautiful stones from the royal collection.

Created by the crown jeweller Augustin Duflot to a design by Claude Rondé, the coronation crown of Louis XV is encrusted with rubies,

topaz, sapphires, emeralds, pearls and the most beautiful diamonds from the royal collection, including the Sancy, the Regent and the

Mazarin diamonds.

A month after the coronation, the newspaper ‘Le Mercure’ published an issue running to several hundred pages reporting every detail of the coronation. In it, the crown is described precisely: ‘The heads of the eight fleurs-de-lys are formed from table-cut gems known as the Mazarin diamonds’.

After the coronation, and at the request of the king, the crown was completely stripped of its precious stones, which were replaced with

copies in glass. Having escaped destruction in subsequent centuries, it is now the property of the Musée du Louvre, where it remains on

public display.

Louis XV, King of France, by Louis-Michel van Loo, 18th Century © Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rennes, France / Bridgeman Images.

‘Journal du voyage du Roy a Rheims’, Mercure, November 1722 © Bibliothèque Nationale de France

The crown of Louis XV, 1722 (gilded silver, replacement stones and pearls) © Musée du Louvre / Peter Willi / Bridgeman Images.

A new inventory of the French Crown jewels was made following the death of Louis XV in 1774. Again, the Grand Mazarin still occupied a prominent place and had returned to the famous chain of diamonds.

The young Dauphin would succeed his grandfather just before his 20th birthday. The court jeweller Aubert was responsible for creating the new crown. Since Louis XV had been crowned at the age of 12, his crown was therefore too small for the new monarch. Aubert took his inspiration from this earlier crown to create a very similar design set with the same stones in a slightly different order. In fact, the two crowns are so similar that once the coronation was over and the jewels had been removed, it was the Louis XV crown that was depicted in the official portraits of Louis XVI.

Once again, the Grand Mazarin was removed and returned to join the other diamonds of the Crown jewels for the use of King Louis XVI

and Queen Marie-Antoinette.

The reign of Louis XVI would be turbulent to say the least, and the destiny of the diamond would prove both fantastic and incredible.

Louis XVI in royal costume, by Joseph Duplessis, 1777 © Musée Ingres, Montauban, France / Bridgeman Images.

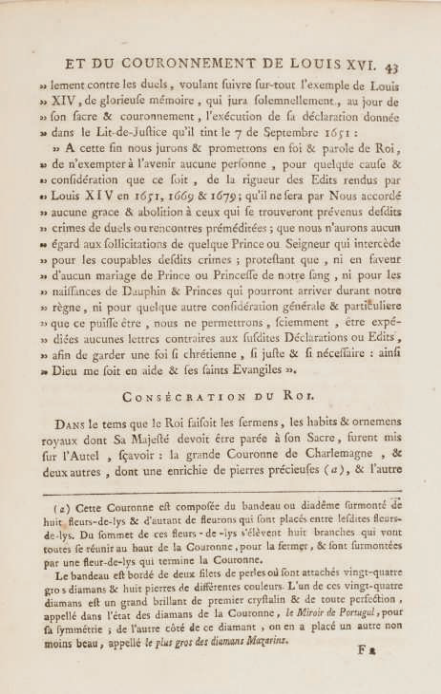

Abbé Pichon and M. Gobet, Le journal historique du sacre et du couronnement de Louis XVI, 1775 © Bibliotheque Nationale de France.

In 1792, the French Revolution had been underway for three years. Severely weakened, King Louis XVI was forced to hand over all the property of the French Crown, which was now stored in the Hôtel du Garde-Meuble (the Royal Treasury). The publication in 1791 of a complete inventory of the French Crown jewels convinced a group of around thirty plotters to pull off the crime of the century

Having first broken into the building - which is still there today on the Place de la Concorde in Paris - the robbers broke open the main cabinets and seized all the French Crown jewels.

The outrage and subsequent investigation were headline news in every French newspaper. Together with all the finest diamonds in ,

the Grand Mazarin had simply disappeared. Some would never be recovered.

Ill-prepared from the start, most of the thieves were soon arrested and sentenced to death. One of them - Depeyron - begged to be spared

the scaffold in return for surrendering his portion of the spoils. Escorted to his home in a dead-end street called Sainte-Opportune, he opened the roof window, reached out and handed back to the authorities a bag containing a number of diamonds. And so the Hortensia and Grand Mazarin diamonds were rediscovered...

Very fortunately, the 1791 inventory had provided crucial information for identifying the stone. In fact, the Grand Mazarin had been re-cut just before the inventory was compiled into a square brilliant with rounded corners, losing several carats in the process to emerge with a recorded weight of 18 9/16 (old) carats.

But the dramatic theft from the Garde-Meuble was by no means the last adventure for the Grand Mazarin…

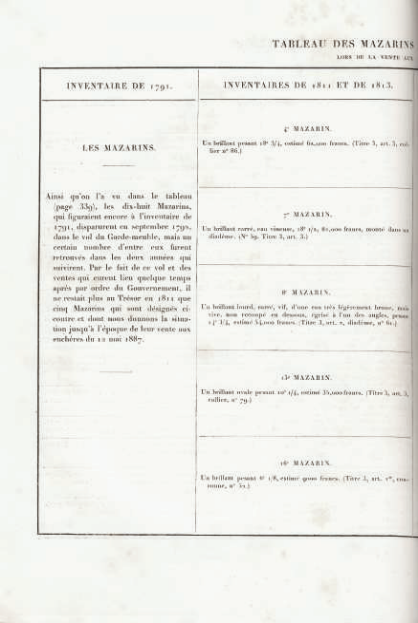

French Crown Jewels Inventory, 1791 © Bibliotheque Nationale de France.

The fall of the monarchy cast a silence over the fate of all the French Crown jewels, but the rise of Emperor Napoleon I brought with it a new fashion for celebrating the splendours of the past. He had the Regent diamond mounted on the hilt of the consular sword and showered both his wives with gold and diamonds.

In 1810, the Emperor commanded the renowned jeweller François-Regnault Nitot to create a magnificent set of diamond jewellery for his wife Marie-Louise. It included a crown, a diadem, a necklace, a comb, a pair of three-drop earrings, a pair of bracelets, a belt, ten dress jewels and eight rows of gold collets.

The diadem is set with the most beautiful of the crown diamonds. In the centre is the Fleur-de-Pêcher above the Mazarin VIII diamond and framed by the Grand Mazarin to the left and the King of Sardinia diamond to the right.

The reign of the emperor was to be short, but significant. On his return to Paris, King Louis XVIII seized the jewels surrendered by the Emperor and Empress, and gave certain pieces, including the diamond diadem, to Paul-Nicolas Meinière. He asked him to remove the stones from their settings to create a new set of jewellery for the Duchess of Angoulême.

But since the Grand Mazarin was not used in the new jewellery, it was returned by Meinière to the crown for re-use in royal jewellery of

the future.

Napoleon I on the Imperial throne, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1806 © Musée de l’Armée, Paris, France / Bridgeman Images.

Marie-Louise of Austria, Empress of the French, by Robert Lefèvre, 1812 © De Agostini Picture Library / G. Dagli Orti / Bridgeman Images.

G. Bapst, Histoire des Joyaux de la Couronne de France, 1889

B. Morel, The French Crown Jewels, 1988.

King Louis XVIII considered coronation, but eventually rejected the idea. His crown was created but never used, and the stones it contained - diamonds and sapphires - were reset for other purposes.

When his successor Charles X was crowned in May 1825, it was with the crown of Louis XVIII, which he had asked the jeweller Bapst to adapt for the purpose. In reality, the crown was largely reworked and simplified to his design. Although the transformation required

fewer sapphires than the original crown, it did make use of the great diamonds of the royal collection once again.

The De Guise, the Fleur-de-Pêcher and the Grand Mazarin diamonds were therefore among those used to crown King Charles X.

But after the splendour of the event, the Grand Mazarin was very rarely seen. The successor to Charles X, Louis Philippe, never used the French Crown jewels, so the Grand Mazarin and all the other diamonds of the crown collection remained in the guardianship of the administration of the civil list until 1848 without ever being used by any member of the royal family.

Charles X in his coronation robes, by Baron Francois Gerard, 1825 © The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, County Durham, UK / Bridgeman.

When preparing for his coronation, which never happened, Emperor Napoleon III could not use the fleur-de-lys crown of Charles X. It was therefore completely stripped bare of its stones to leave only the basic structure. In this crown, the fleurs-de-lys are replaced by the Imperial emblem of eagles.

In the event, two crowns were produced in succession; the first in 1853, followed by the second and definitive model in 1855, both created by the jeweller Lemmonier.

The second crown, which was also to be the last French crown, was shown at the 1855 World Fair in Paris. It was set with emeralds and the finest of the diamonds from the royal collection, the only exception being the Regent diamond. Once again, the Fleur-de-Pêcher and Grand Mazarin foundthemselves reunited and set on the most important jewel of France.

Napoleon III, by Winterhalter, 1855 © De Agostini Picture Library / G. Dagli Orti / Bridgeman Images.

For its final days in the company of France’s reigning family, the Grand Mazarin became one of the jewels owned by Empress Eugénie. A woman of great elegance, Eugénie de Montijo was very much a role model for the women of France. She commissioned the very finest jewellery from France’s most gifted and exceptional jewellers.

The Grand Mazarin therefore returned to the jewel cabinet of the Empress, set in a single collet with small hoop that could be sewn onto fabric bows to complement her outfits.

It was in this form that the Grand Mazarin would leave the Crown jewels forever to remain a permanent and very privileged witness to key moments in French history.

Empress Eugénie, by Winterhalter, 1853 © Château de Versailles / Bridgeman Images.

Following the fall and exile of Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie, the French Crown jewels found their way into the cellars of the Ministry of Finance.

They first emerged for the 1878 World Fair held on the Champs de Mars in Paris, where they were exhibited in a special showcase for delight of visitors.

It was not until 1884 that they would reappear, this time in the state rooms of the Musée du Louvre for an exhibition of Crown jewels in preparation for their future sale.

The plan to sell off the French Crown jewels was crystallised soon after, and was published in the Official Journal of the French in 1887.

Despite vociferous opposition, the auction was held in May 1887. A few historic diamonds, including the Regent, narrowly escaped the dispersal. But the Grand Mazarin was not spared in the same way.

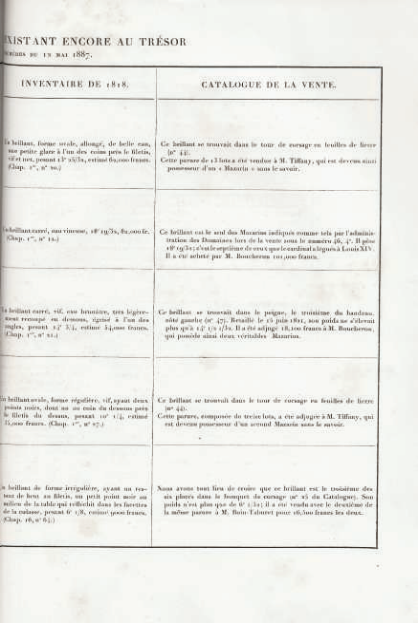

Very little attention was paid to the catalogue for the sale, which contained what remained of the splendours of the French monarchy. number 46 was a lot of 7 diamonds described as the last remaining Mazarin diamonds.

The fourth on the list is a ‘brilliant cut weighing 18 carats 19/32’, still set in the collet created for Empress Eugénie.

The Grand Mazarin was beginning a new chapter in its illustrious history...

The French Crown Jewels exhibited at the Paris World Fair, 1878.

L. Enault, French Crown Jewels, exhibition catalogue, 1884, Musée du Louvre, Salle des États.

Auction catalogue of the French Crown Jewels, 1887.

Auction catalogue of the French Crown Jewels, 1887.

Auction catalogue of the French Crown Jewels, 1887. Photo by Berthaud.

The protesters were deeply offended by the sale of jewels from the French royal collection. But these were troubled times, and France cared little about the sale of these exceptional jewels. Few of the great French jewellers deigned to attend the sale, and the American house of Tiffany would prove to be the most active bidder.

If there was one jeweller who really understood the importance and unique opportunity presented by such an event, it was undoubtedly

Frédéric Boucheron. Recognised by his guild as one of its staunchest members, he was also one of the favoured jewellers of France’s great families.

His elegant designs and talented workshop attracted not only an international client base, but also many prizes at a variety of different exhibitions.

A fine connoisseur of French history, he knew that only one of the seven stones described as the last Mazarin diamonds was authentic.

The exact weight listed in the last inventory of French Crown jewels in 1818, together with the light pink colour of the stone (which the catalogue neglected to mention), left him in no doubt. This was the seventh of the original Mazarin diamonds: the Grand Mazarin.

Bought for 101,000 French Francs - a very large sum at the time - the diamond and one other of the diamonds sold from the same collection would later be mounted into a brooch commissioned by Russian aristocrat Baron von Derwies. Heir to one of the French court jewellers, Germain Bapst wrote to Frédéric Boucheron to congratulate him on having bought ‘the only authentic Mazarin’ in the sale.

The Grand Mazarin left the expert hands of one of France’s greatest jewellers in 1888 to travel to Russia, leaving behind it a now Republican France with little appetite for celebrating the splendours of its former history.

Frédéric Boucheron © Boucheron Archives.

Invoice in the name of Boucheron for the Grand Mazarin, lot 46 of the French Crown Jewels auction, 1887 © Boucheron archives.

‘Histoire des Joyaux de la Couronne de France’, by Germain Bapst, 1889.

In 1962, the Louvre Museum held an exceptional exhibition celebrating ‘Ten Centuries of French Jewellery’.

From 3rd May to 3rd June that year, the Louvre showcased the most important jewels ever produced in France. A colossal amount of research was required to reunite the stones and jewels that together constituted the glory of the country’s jewellery history.

A very special place was reserved within the exhibition for the French Crown jewels, their history now appreciated for its full and real.

Listed as number 22, between the legendary Regent and Sancy diamonds, the Grand Mazarin, on loan from a ‘Private Collection’, finally regained its former glory.

But this would be the last time it was ever exhibited in public, and it disappeared again for more than half a century.

‘Dix siècles de joaillerie française’, exhibition catalogue, Musée du Louvre, 1962.

Christie's. Magnificent Jewels, 14 November 2017, Geneva

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F98%2F16%2F119589%2F94357347_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F44%2F83%2F119589%2F76408102_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F97%2F119589%2F74796942_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F88%2F75%2F119589%2F71849039_o.jpg)