The Huntington Mansion rénové

Jori Finkel writes: Walking through the newly renovated Huntington mansion, John Murdoch makes it clear that he would rather not discuss “The Blue Boy,” once heralded as the most expensive painting ever sold. It was purchased in 1921 by the railroad tycoon Henry E. Huntington for £182,200 (roughly $700,000 at the time, or $8 million today).

“The problem is, there’s a tendency of people to say, I don’t need to go to the Huntington because I’ve seen ‘Blue Boy,’ ” he said. “It’s like people at the Louvre running through the museum to see the Mona Lisa and missing everything along the way.”

Photo: Courtesy of the Huntington Library

Now, as Mr. Murdoch prepares to reopen the mansion on Wednesday after a three-year shutdown and a $20 million renovation, his goal is just the opposite: to slow down the crowds by offering different points of interest.

“If we can get someone who normally spends one minute in a room to stop and spend two minutes there,” he said, “that’s the best measure we have of how well we’re doing our job.”

John Murdoch at the Huntington Mansion. Photo: J. Emilio Flores for The New York Times

Mr. Murdoch hopes that visitors will relax in the new rattan chairs on the house’s rebuilt loggia, enjoying the potted orchids and Roman sarcophagi at hand and the Huntington gardens — some 120 acres in all — in the distance.

Photo: Tim Street-Porter, Courtesy of the Huntington Library

He hopes that they will stop and notice the modeling on the face on Jean-Antoine Houdon’s original 1782 life-size bronze of Diana the Huntress.

In essence he wants them to luxuriate in the textures, colors, artworks and objets d’art that make up one of the great Gilded Age estates west of the Mississippi, an Italianate villa that Henry E. Huntington once called his ranch.

Photo: Tim Street-Porter, Courtesy of the Huntington Library

In 1907, when he hired the architect Myron Hunt to build the Beaux-Arts house, Mr. Huntington was newly divorced and preparing to retire from the railway business that had made him and his uncle Collis P. Huntington both millionaires many times over. He was ready to devote himself to nature, literature and art.

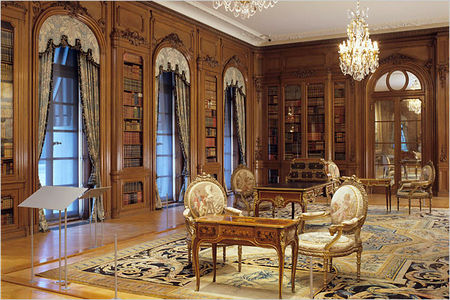

If this house was a businessman’s Arcadian dream from the start, today it remains a fantasy of another sort. The main floor still has period rooms evoking the often-bookish aspirations of Mr. Huntington and the more lavish “gout de Rothschild” aesthetic of his second wife, Arabella (who had previously, and scandalously, been married to his uncle Collis).

Photo: J. Emilio Flores for The New York Times

The Grand Library brings together numerous leather-bound books, four Beauvais tapestries, and two Savonnerie carpets that were originally commissioned by Louis XIV.

But generally the curators did not attempt the kind of slavishly detailed re-creations associated with historic houses, as correspondence reveals that rooms were constantly rearranged to accommodate a steady stream of European masterpieces. And very few photographs of the mansion’s original interior have survived.

Photo: Tim Street-Porter, Courtesy of the Huntington Library

Instead the curators have reconceived the first floor to convey a general sense of the Huntingtons’ tastes. They have also transformed the second floor into a sequence of intimate galleries for European art. (American art is housed elsewhere on the property.)

In effect they have transformed one of the great American house-museums — that odd and theatrical genre of private spaces on public display — into more of a museum than ever before.

The small drawing room on the first floor. Photo: Tim Street-Porter, Courtesy of the Huntington Library

Upstairs, one new suite of galleries features 18th-century French sculpture and decorative arts drawn from a large memorial collection Mr. Huntington assembled in honor of Arabella in 1926, two years after her death. These pieces, including a trove of top-quality Sèvres porcelain that fills what was once the master bedroom, have never before been exhibited in the mansion.

A room with Sèvres porcelain in the Huntington Mansion. Photo: Tim Street-Porter, Courtesy of the Huntington Library

Downstairs, the art is strategically arranged to animate different domestic spaces. A small drawing room features charming 18th- century British portraits of women peering coyly from behind extravagant hats.

“What I have in mind with all of these rooms is: When you’re taking a class of graduate students around a gallery, is the hang there useful? Do you have something to talk about?” said Mr. Murdoch.

"Emma Hart, later Lady Hamilton, in a Straw Hat" circa (1782-1784) by George Romney. Photo: Tim Street-Porter, Courtesy of the Huntington Library

Mr. Murdoch in the newly renovated dining room. He turned the corner into the handsome dining room, lined with British landscapes from the late 18th century. In that era, he said, “the theory of propriety in picture-hanging said that you should put up something safe like flowers or landscapes. You absolutely do not want to put up pretty ladies, certainly not your wife and daughter, lest guests cast lascivious eyes.”

Photo: J. Emilio Flores for The New York Times

Another addition is a set of marble busts, mainly 18th-century, by artists like Joseph Nollekens and Louis-François Roubiliac. Here too Mr. Murdoch has a bit of an agenda: to save the sculptures from being seen as mere décor. “Apart from just putting all the swanky objects in one room, you should be able to use this room to discuss portraiture in the highest media, painting and sculpture,” he said.

The Thornton Portrait Gallery.. Photo: John Edward Linden, Courtesy of the Huntington Library

Visitors will also notice that the 14 full-length British portraits in the gallery have been rearranged, creating new juxtapositions and pairings. One coupling to be expected is “The Blue Boy” and Thomas Lawrence’s portrait of the young Sarah Goodin Barrett Moulton, better known as “Pinkie,” which face each other across the long space. The paintings are often twinned in the popular imagination, perhaps because of their colorful titles.

Mr. Murdoch has another take: “The two paintings have nothing to do with each other art-historically. They’re just associated because they were both controversial exports from England.”

A portrait of Sarah Goodin Barrett Moulton, also known as “Pinkie”, (1794) by Thomas Lawrence

In a less likely pairing, Reynolds’s 1784 portrait of the actress Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse, flanked by ghostly visions of pity and terror, hangs across from Gainsborough’s 1777 portrait of the Baroque composer Carl Friedrich Abel at his writing desk with his viola da gamba at his feet. Both works celebrate artists, not your usual aristocrats. And both depict the genesis of artistic inspiration.

That choice reflects a larger and bolder principle that guided the entire project. “There was nothing wrong with putting Mrs. Siddons at the far end of the gallery,” Mr. Murdoch said of her previous perch. “But whenever we had the choice of changing something or not, we’ve opted to change it. We want to help people see the collection in a new light.”

A portrait of Sarah (Kemble) Siddons by Joshua Reynolds. Photo: Tim Street-Porter, courtesy of the Huntington Library

Lire l'article "Attention, ‘Blue Boy’ Fans: Slow Down" By JORI FINKEL http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/25/arts/design/25fink.html?partner=rssnyt&emc=rss&pagewanted=print

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240515%2Fob_ad0b40_telechargement-6.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240515%2Fob_a1c116_telechargement-4.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240515%2Fob_e979bd_telechargement-2.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240515%2Fob_3389d0_telechargement.jpg)