"Balenciaga and Spain" @ de Young Museum

Cristobal Balenciaga. Detail of cocktail dress of fuchsia silk shantung and black lace with black silk satin ribbons, summer 1966

SAN FRANCISCO, CA.- You can feel the pulse of Spain beat in every garment in Balenciaga and Spain. A dress ruffle inspired by the flourish of a flamenco dancer’s bata de cola skirt; paillette-studded embroidery that glitters on a bolero jacket conjuring a nineteenth-century traje de luces (suit of lights) worn by a matador; clean, simple, and technically perfect lines that extrapolate the minimalist rhythms and volumes of the vestments of Spanish nuns and priests; a velvet-trimmed evening gown aesthetically indebted to the farthingale robe of a Velázquez Infanta.

On March 26, 2011, the de Young Museum in San Francisco opens Balenciaga and Spain, an exhibition curated by Hamish Bowles, European editor at large of Vogue, featuring 120 haute couture garments, hats, and headdresses designed by Cristóbal Balenciaga (1895–1972). The exhibition illustrates Balenciaga’s expansive creative vision, which incorporated references to Spanish art, bullfighting, dance, regional costume, and the pageantry of the royal court and religious ceremonies. Cecil Beaton hailed him as “Fashion’s Picasso,” and Balenciaga’s impeccable tailoring, innovative fabric choices, and technical mastery transformed the way the world’s most stylish women dressed. The exhibition closes on July 4, 2011.

A symposium organized by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco that focuses on the influence of Spanish culture on the work of Balenciaga will also take place at the de Young on March 26 and features speakers Hamish Bowles; Pamela Golbin, chief curator of the Musée de la Mode et du Textile at the Louvre; Miren Arzalluz, curator of the Balenciaga Foundation and author of Cristóbal Balenciaga: La forja del Maestro (1895–1936); and Lourdes Font, associate professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology. The Balenciaga symposium will be available for viewing via the Internet on FORA.TV for $9.95 as a live broadcast on March 26 and for unlimited, on demand viewing during the run of the exhibition. For additional information, visit fora.tv/conference/Balenciaga_and_Spain.

The exhibition originated in 2010, in a presentation at the Queen Sofía Spanish Institute in New York City titled Balenciaga: Spanish Master. The exhibition was conceived by Oscar de la Renta, who began his career in fashion working at Balenciaga’s Madrid couture house in the 1950s. De la Renta invited Hamish Bowles to curate the exhibition. For the de Young Museum, the themes are expanded to include twice as many objects, drawn from museum and private collections around the world and including an unprecedented loan of 30 pieces from the House of Balenciaga in Paris, which generously opened its archives of historically significant Cristóbal Balenciaga garments, iconography, and related materials. In addition to displaying eight garments from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s own significant collection of Balenciaga, the exhibition features loans (some of which have never been exhibited before), from a number of important international institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Musée de la Mode et du Textile and the Musée Galliera in Paris, the Museum of the Fashion Institute of Technology, the Hispanic Society of America, LACMA, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of the City of New York, the Phoenix Art Museum, and the Texas Fashion Collection, as well as private couture collectors such as Sandy Schreier. A special loan of seventeen pieces comes from Hamish Bowles’s own collection. The ensembles featured include garments commissioned and worn by some of the world’s most iconic tastemakers, among them Doris Duke, Baroness Pauline de Rothschild, Countess Mona Bismarck, Gloria Guinness, Ava Gardner, Thelma Chrysler Foy, Claudia Heard de Osborne, and the Bay Area’s own Eleanor Christenson de Guigné and Elise Haas.

As legendary fashion editor Diana Vreeland vividly described him, “Balenciaga was the true son of a strong country filled with style, vibrant color, and a fine history,” who “remained forever a Spaniard… His inspiration came from the bullrings, the flamenco dancers, the fishermen in their boots and loose blouses, the glories of the church, and the cool of the cloisters and monasteries. He took their colors, their cuts, then festooned them to his own taste.” Curator Hamish Bowles notes, “Balenciaga’s ceaseless explorations and innovations ensured that his work was as intriguing and influential in his final collection as it had been in his first.”

Balenciaga and Spain begins with an introductory gallery featuring three decades of Balenciaga’s signature silhouettes, all in tones of black, that demonstrate his mastery of volume, his sophisticated use of fabric and embellishments, and his supreme technical innovations. The exhibition then unfolds in six areas of focus:

Spanish Art — Balenciaga drew inspiration from the great artists of Spain: the atmospheric color palette of Goya, Velázquez’s portraits of courtiers and royalty, and the draped volumes of fabric in El Greco’s and Zurbarán’s haunting seventeenth-century images of saints. Included in the exhibition is Balenciaga’s iconic 1939 Infanta dress, a modernist interpretation of the dresses worn by the Infanta Margarita in Velázquez’s celebrated portraits—an inspiration that he revisits in a smart lace-trimmed day suit of 1938. Late in his career, Balenciaga turned to contemporary Spanish art and was inspired by the abstraction of Joan Miró’s paintings and the modernist, monumental sculptures of Basque countryman Eduardo Chilida.

Dance — Whether he literally represented it in such recognizable elements as the bata de cola (dress with a ruffled train) of the flamenco dancer, or more loosely suggested it in the use of lunares (polka-dot patterns), a bold, traditional print used in flamenco costumes, Balenciaga incorporated and abstracted the rich culture of Spanish dance in his work, using tiers of fabric, ruffles, flounces, and fabric choices that accentuated movement. Balenciaga was also captivated by the traje corto costume of the male flamenco dancer and deconstructed its elements of close fitting cropped bolero, cummerbund, and tight pants into his work. Flamenco’s influence can be seen in whimsical hats that accessorize the ensembles, simulating a flower tucked in a dancer’s hair or a scarf knotted around the head.

Bullfighting — “From his earliest collections, Balenciaga included designs that contained overt allusions to the costume of the matador,” writes Bowles. Using the traditional stiffened bolero of the matador, decorated with sumptuous embroidery, alamar (frog and braid trimming), and distinctive borlones (pompom tassels), as a starting point, Balenciaga softens the silhouette for his female clients throughout the 1940s and early 1950s. Here he collaborates with embroidery houses such as Bataille and Lesage to re-create the passmenterie, beading, and embroideries of the matador costumes, themselves as intricate as haute couture garments. By the 1960s, Balenciaga takes these embroideries and embellishments out of the traje de luces context and uses them as decoration on eveningwear and millinery. Inspiration also comes from the color palette of the matador’s capes and his work includes splashes of bright fuchsia, deep red, and vibrant yellow. Even the carnation, the traditional flower thrown in tribute to matador at the end of a successful bullfight, appears in Balenciaga’s work in embroideries and printed fabric.

Religious Life — A devout Catholic all his life, who once considered joining the priesthood, Balenciaga was deeply moved by both the everyday dress and the pageantry of the Spanish church. He reinterpreted elements suggesting a nun’s habit, a priest’s embroidered chasuble or severe black cassock, a monk’s hooded robe, and even the spectacular, brilliantly colored and embellished robes that clad the statues of the Madonna carried through the streets of Spain during Holy Week. It is here that Balenciaga’s technical mastery and tailoring shine as he plays with ideas of volume, structure, and linear purity.

The Spanish Court — “The dress of Spain’s monarchs, their families, and their courtiers, depicted in some of the most striking portraiture in the history of art, exerted a powerful effect on Balenciaga’s creative imagination,” notes Bowles. For example, he references early-seventeenth-century farthingales, distinctive features of Spanish court dress for three centuries, in a literal way, with silhouettes featuring exaggerated hips, and then abstracts them later in his career in the six-pointed peplums of evening gowns. Sumptuous embroideries, ermine tails, and pearl details present luxurious, contemporary versions of royal themes.

Regional Dress — Balenciaga’s imagination was fueled with ideas driven by the diverse regional costume of Spain and by some of the original folkloric pieces that he gathered for his personal collection. He translated traditional Spanish garments such as a mantón de Manila, a fringed silk shawl embroidered with brilliant floral motifs, into haute couture embroideries by Lesage that he used to decorate spectacular evening clothes. His shaggy vests of innovative mohair textiles recall the practical garments of a Navarran shepherd. Humble cloaks and capes reappear in sumptuous fabrics with voluminous lines. Loose, unfitted cotton piqué blouses evoking fishermen’s shirts recall the clothing of his Basque homeland. “Balenciaga revolutionized fashion by referencing the sturdy, utilitarian garments worn by the Spanish laboring classes—as well as the attitude and philosophy that shaped them—to create a new paradigm of mid-century elegance,” explains Bowles.

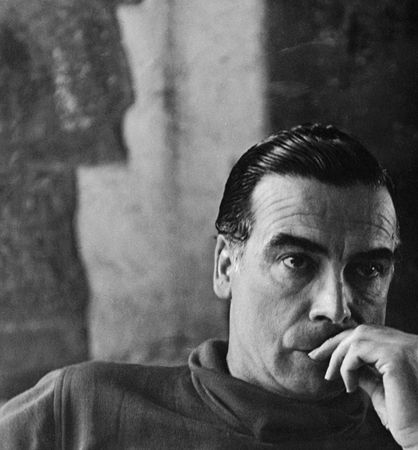

Cristóbal Balenciaga (circa 1952). © Bettmann/CORBIS

Left: Bolero of garnet velvet and black jet embroidery, winter 1947. Collection of The Costume Institute of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photograph by Craig McDean. Center: Detail of evening bolero jacket of burgundy silk velvet and jet and passementerie embroidery by Bataille, winter 1946. Collection of Hamish Bowles. Photo by Kenny Komer. Right: Scarlet silk ottoman evening coat with capelet collar, autumn/winter 1954–1955. Collection of The Costume Institute of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photograph by Craig McDean

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F97%2F38%2F119589%2F31737909_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F24%2F64%2F119589%2F129100261_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F89%2F93%2F119589%2F127899898_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F00%2F59%2F119589%2F126968614_o.jpg)