Orientalist masters at Sotheby's spring auction of 19th Century European Art in New York

NEW YORK, NY.- Sotheby’s spring auction of 19th Century European Art in New York on 9 May 2013 will feature an exceptional collection of Orientalist paintings. The group is highlighted by four major works by the master of the genre, Jean-Léon Gérôme, including Le Tigre et le Gardien (est. $300/400,000), as well as The Colossus of Memnon (est. $400/600,000). While he painted the Colossus a number of times and from different viewpoints throughout his career, this early work was devised on his first ambitious and long anticipated visit to Egypt in 1856. Also included in the sale is Une Journée Chaude au Caire (Devant la Mosquée) (est. $150/250,000) and a rare sculpture by Gérôme, Corinthe, a gilt bronze model, cast by the renowned Parisian foundry Siot (est. $50/70,000).

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 - 1904), Le Tigre et le Gardien. Oil on canvas, 18 1/4 by 15 1/8 in. 46.3 by 38.4 cm; signed J.L. GEROME. (lower left). Est. $300/400,000. Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: Bernard K. Crawford, Lyndhurst, New Jersey

Private Collection, New York

LITERATURE: Gerald M. Ackerman, The Life and Work of Jean-Léon Gérôme, with a Catalogue Raisonné, New York, 1986, p. 248, no. 299 (as The Grief of the Pasha (variant), measurements reversed and some information inverted with no. 300)

Gerald M. Ackerman, Jean-Léon Gérôme, monographie révisée, catalogue raisonné mis à jour, Paris, 2000, p. 302, no. 299 (as La douleur du pacha, le tigre mort, measurements reversed and with incorrect provenance), illustrated

NOTE: In 1885, Jean-Léon Gérôme painted The Grief of the Pasha (Joslyn Art Museum), a picture featuring the massive and lifeless body of a Bengal tiger (fig. 1). Immediately purchased by an American collector for the impressive sum of 30,000 francs and hailed by modern scholars as “one of the finest canvases produced by Gérôme during this period” (The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1824-1904, exh. cat., J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, and travelling, 2010, p. 204), this painting has only one documented variant in oil, the present work. More intimate in scale and somewhat starker in detail, the present work nevertheless includes all of the most significant features of The Grief of the Pasha while also introducing a new emphasis on costume – one of the most highly valued hallmarks of Gérôme’s distinctive Orientalist style.

The extraordinary subject of the present work alludes to a poem of the same name, written by Victor Hugo in 1827 and included in the published collection, Les Orientales. When asked to illustrate a new edition of this volume in 1882, Gérôme chose as the frontispiece a drawing inspired by the concluding verse of the poet’s “La Douleur du Pacha”: “No, no, ‘tis not those dismal figures who/inspire his wretched soul’s remorse/through shadowy visions that gleam with blood./What, then, ails this Pasha, beckoned by war/yet weeping like a woman, vacant and sad?/-his Nubian tiger is dead.” This drawing, a reimagined Lamentation scene, would later become The Grief of the Pasha.

In both The Grief of the Pasha and the present work, Gérôme includes a seated Arab man in an ornate setting. Here, the background architecture derives from the artist’s sketches of the Alhambra, which he visited first in 1873 and again a decade later, and from a cache of photographs in the artist’s collection by Juan Laurent (1816-1892). (In Le tigre et le gardien it is a portion of the Arrayanes courtyard that the artist portrays.) The man – the grieving Pasha of

the paintings’ titles – contemplates the dead tiger before him, which lies on a dark blue Oriental rug. (Though the central medallion in the present work suggests that it is a prayer rug, the peculiar cruciform-shape of the stylized motif defies convention.) The man is positioned closer to his beloved pet in the present work than in the larger version, and wears markedly different clothing. Indeed, he is outfitted in the colorful dress of a nineteenth-century Cairo soldier, recorded by Gérôme in several of his most celebrated works; the man’s pink satin sleeves, burgundy salvars, and distinctively wrapped turban are rendered with an ethnographer’s accuracy, as are the pair of ornately carved and decorated flintlock pistols tucked into his belt. (An Ottoman saber, or yatagan, is also visible at his waist.) The benign presence of these weapons is a poignant reminder of the tiger’s erstwhile danger, as well as the waning power of the,once ferocious Ottoman Empire. The eclecticism of this work – from Spain to India to Egypt – and the unexpected profundity of its message were typical of Gérôme, who often combined meticulously observed ethnographic and,architectural details into a single, seamless, and remarkably compelling whole.

The subject of this work follows a broader, longstanding tradition in Orientalist painting as well. In the early 1830s, Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) had accompanied his friend Antoine-Louis Barye (1796-1875) to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, in order to sketch the newest addition to their menagerie – a Bengal tiger from India. These studies served Delacroix well in a series of vigorous oil paintings created soon after his transformative journey to North Africa, in which tigers are portrayed in the midst of struggle or strife (see The Tiger Hunt, circa 1854, Musée d’Orsay, Paris).

Wealthy European collectors found much to admire in these vaguely Orientalist works, including a heightening of emotion, a pleasurable frisson, and a momentary escape from their modern urban lives.

In the 1870s and 1880s, Gérôme created his own, highly successful series of pictures of lions, tigers, and leopards in varying sizes and qualities to suit nearly every taste and economic class. (Like Delacroix, Gérôme made studies in hisyouth at the Jardin des Plantes, which aided him in this endeavor. For some of the many examples of Gérôme’s tiger series, see Ackerman, 1986, pp 226, 248, 300-1, and passim, plates 191, 300, 537-9, and passim.) Gérôme took particular delight in depicting tigers in the desert, watchfully eyeing advancing troops or running full-tilt towards some unseen prey, or, occasionally, in death, tragically sprawled on the marble floors of a Pasha’s palace, as here, or, equally tragically, wrapped around the shoulders of a pelt merchant in Cairo. The tension between the wild and the tamed, the power of nature and the power of man, and the parallels drawn between the tiger on the prowl and military marauders in foreign lands, seems to have been a resonant theme for this artist, and for contemporary audiences as well.

This catalogue note was written by Dr. Emily M. Weeks.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 - 1904), The Colossus of Memnon. Oil on canvas, 25 1/2 by 32 in. 64.8 by 81.3 cm; signed J.L. GEROME and dated MDCCCLVII (lower center). Est. $300/400,000. Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: Dijon (1858)

Haro (sale, Paris, 1881)

Jay Turner

Sterling H. Sockley House, Regent's Park, London

Arthur Tooth & Sons, London

Henry Wyndham

French & Co., New YorkH. Schickman Gallery, New York

Joseph J. Dodge, Jacksonville, Florida (by 1972)

A Middle Eastern Prince (and sold, Sotheby's Parke Bernet, New York, October 12, 1979, lot 313, illustrated)

Private Collection, California (and sold, Sotheby's, New York, October 24, 1989, lot 65, illustrated)

Private Collector, New York (acquired at the above sale

EXHIBITED: Possibly, Paris, Salon, 1857, no. 1161 (as Memnon et Sésostris)

Poughkeepsie, New York, Vassar College Art Gallery, Gérôme and his Pupils, 1967, no. 2

New York, Schickman Galleries, The Neglected 19th Century, 1970, no. 19

St. Petersburg, Florida, Museum of Fine Arts: Jacksonville, Florida, Cummer Art Gallery, Remnants of Things Past,

1971, no. 52

DaytoLITTERAn, Ohio, The Dayton Art Institute; Minneapolis, Minnesota, The Minneapolis Institute of Arts; Baltimore,

Maryland, The Walters Art Gallery, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), 1972-73, pp. 36-7, no. 5, illustrated

LITERATURE: Théophile Gautier, "Gérôme: Tableaux, Etudes et Croquis de Voyage," L'Artiste, December 28, 1856, p. 23

Fanny Field Hering, The Life and Works of Jean Léon Gérôme, New York, 1892, p. 66

Jean-Léon Gérôme 1824-1904, exh. cat., Musée de Vesoul, 1981, pp. 106-7, mentioned under no. 122

Gerald M. Ackerman, The Life and Work of Jean-Léon Gérôme with a Catalogue Raisonné, London, 1986, p. 48, 200, no. 73, illustrated

Herman de Meulenaere, Ancient Egypt in Nineteenth Century Painting, Belgium, 1992, p. 59, illustrated

Gerald M. Ackerman, Jean-Léon Gérôme, monographie révisée, catalogue raisonné mis à jour, Paris, 2000, p. 232, no. 73, illustrated

NOTE: The Colossi of Memnon have stood guard at the ancient necropolis of Thebes since 1350 BC. Standing at a towering height of 18 meters, they were intentionally imposing and would have made a powerful impression on any visitor. Gérôme was known to have painted the subject a number of times, including a view from the side in The Colossi of Thebes, Memnon and Sesostris (1856, Musée Georges Garrett de Vesoul), Caravan Passing the Colossi of Memnon, Thebes (1857. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes), and the oil sketch of the present view, Memnon and Sesostris (fig. 1, 1856, private collection). The present work, which depicts camels resting beside the colossus of Memnon, lacks the third of the original composition recorded in the Gérôme Paris Photographs at the Cabinet d'Estampes, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris (vol. IV, no. 10) and exhibited at the Salon of 1857 as Memnon et Sésostris. As the placement of the signature and all other details correspond exactly with the original photograph, it is likely that the present picture is a result of the former having been cut down (ommitting the portion with a view of the colossus of Sesostris); alternatively, this might be a second version of the wider composition.

This work was painted after Gérôme's first ambitious and long anticipated visit to Egypt in 1856, a journey which started, as Gérôme himself describes, "with friends, being one of five - all of us with little money and abundant spirits! ... We rented a sailboat and stayed for four months on the Nile, hunting, painting and fishing, from Damietta to Philae... We returned to Cairo, where we passed four months more in a house in old Cairo, which Sulieman Pasha rented to us" (as quoted in Ackerman, 1986, p. 44)

Ackerman writes that in the Salon of 1857 in Paris "several landscapes drawn from the experinces of this trip were exhibited. The vigor of the drawing, the strength of the touch, and lack of refinement makes it seem almost as if the picture were painted on the spot or on the houseboat where the painter maintained a studio. The brightness of the light makes it seem painted in immediate reaction to the blinding light of Egypt, without aesthetic monitoring. Of all Gérôme's Egyptian pictures, only a few have the feeling - like this one - of having been painted on location" (JeanLéon Gérôme, 1972-73, exh. cat., p. 36).

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 - 1904), Une Journée Chaude au Caire (Devant la Mosquée). Oil on canvas, 25 3/4 by 18 in. 65.4 by 45.8 cm; signed J.L. GEROME (center right, below the awning). Est. 150,000 - 250,000 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: Hammer Galleries, New York (and sold, Parke-Bernet, New York, March 12, 1969, lot 98, illustrated)

Dr. James Nelson

Private Collection (and sold, Sotheby's, New York, May 24, 1988, lot 40, illustrated)

LITERATURE: Gerald M. Ackerman, The Life and Work of Jean-Léon Gérôme, with a catalogue raisonné, London, 1986, pp. 270-1, no. 403, illustrated

Gerald M. Ackerman, Jean-Léon Gérôme, monographie révisée, catalogue raisonné mis à jour, Paris, 2000, p. 333, no. 403, illustrated

NOTE: Called “the city of a thousand minarets,” Cairo captivated Western artists during the nineteenth century with its distinctive skyline and wide array of elaborately decorated religious structures. Jean-Léon Gérôme’s many paintings of the interiors and exteriors of Cairene mosques form an important subgenre within his expansive Orientalist oeuvre, and indicate the artist’s deep appreciation of both local culture and historical accuracy. The architectural precision of the individual components of these works, however, attributable to Gérôme’s vast library of contemporary photographs and the numerous studies that he made during his travels abroad, is oftentimes deceiving: the artist’s imaginative reconfigurations of Cairo’s religious topography defy any attempt at map-making, and elevate Gérôme’s paintings from mere documentation to the realm of well-composed art.

In the present work, three sunlit minarets are silhouetted against a brilliant blue sky. In reality, they are separated by many miles of twisting, turning streets, while in Gérôme’s painting, they are effortlessly brought together for picturesque effect. On the left is the minaret built by Sultan al-Ghuri at ‘Arab Yasar (1510 AD) on the western side of Cairo’s Suyuti cemetery (fig. 1). Rather than standing above the roof of the mosque, as do most medieval minarets, with a first gallery well above adjacent rooftops, it flanks the mosque’s northern corner at street level. To the right of this unusual structure —again, on canvas if not in fact — is the short-lived mabkhara, or incense-burner, style minaret of Sultan Baybars al-Jashankir (1303-4 AD). Its ribbed helmet, which rests on a pierced pavilion atop a cylinder, was once decorated with green ceramic tile — the earliest example of a minaret adorned in this way. Its lower rectangular shaft features the ablaq courses of contrasting colored stone and the crowning bunches of stucco stalactites that distinguish Mamluk-era architecture. A favorite of Gérôme’s, this minaret can be seen in several other works dating from the early 1890s (see: Vue du Caire, 1891; Une journée chaude au Caire [variation], 1890, both illustrated in Ackerman, 1986). The central minaret, with its pencil-shaped Ottoman turret, is also repeated in compositions from this time (see: The Minarets, circa 1891, Haggin Museum, Stockton, California). (Studies for this minaret, as well as several others, are housed at the Musée Georges-Garret, Vesoul.) The dramatic emphasis on vacant space in the foreground of Gérôme’s painting, on the other hand, broken only by a wandering dog and the gangling form of a patient camel, may be traced to a much earlier work — The Death of Marshall Ney (1868, Sheffield City Art Galleries). The presence of the blue-robed muezzin on the first gallery of the al-Ghuri minaret links Une Journée Chaude to additional masterpieces from the 1860s – notably, the hauntingly beautiful series of prayer paintings that he produced after a second Egyptian tour (see: Prayer on the Housetops, 1865, Kunsthalle, Hamburg; and Muezzin [Call to Prayer], 1866, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska).

This catalogue note was written by Dr. Emily M. Weeks.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 - 1904), Corinthe. gilt-bronze with semi-precious stones, height: 29 inches, 73.5 cm. Est. 50,000 - 70,000 USD. Photo: Sotheby's

PROVENANCE; Sale: Sotheby's New York, October 23, 1990, lot 56, illustrated

Private Collection, New York

LITERATURE: Gerald Ackerman, Jean-Léon Gérôme, Monographie révisée. Catalogue raisonné mis à jour, Paris, 2000, p. 382-383, S 9

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), L'Histoire en spectacle, exh. cat., Musée d'Orsay, Paris, 2010, p. 326-328, nos. 192 - 193.

NOTE: The present gilt bronze model, cast by the renowned Parisian foundry Siot, is directly drawn from what is undoubtedly the most iconic sculpture of Jean-Léon Gérôme’s oeuvre. The original plaster model was created in 1903-4, and was certainly the last sculpture made before his death (sold, Sotheby's Paris, June 25, 2008, lot 38, now held by the Musée d’Orsay). Although the polychrome and wax plaster model can be viewed as a finished work itself, it was nonetheless a model for a larger marble version meant to be presented at the 1904 Paris Salon as number 2922 and described as follows: "une femme nue couverte de veritable bijoux est assise sur le chapiteau d’une colonnecorinthienne en marbre vert”.

Gerald Ackerman recorded no more than six bronze casts in either gold or silver finish. They all were cast by Siot and measure 70 cm in height. One of the six was in the collection of Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge, and sold in these rooms February 20, 1976

American artist Frederick Arthur Bridgman, known for painting imagery from North Africa and the Middle East, is well represented in the sale with two works, including the magnificent The Diversion of an Assyrian King (est. $400/600,000). A pupil of Gérôme, Bridgman made his name winning a medal at the 1877 Salon and a place at the Paris Exposition Universelle with Les Funerailles d’une momie. The current work was the second of three highly acclaimed historical reconstructions that Bridgman painted in three consecutive years. The light palette and rigorous brushwork in certain passages of the picture – trademarks of his maturing style – were widely commented upon, perhaps due to the uncommonness of these formal elements in academic history painting. Also included in the sale by Bridgman is An Egyptian Procession (est. $200/300,000).

Frederick Arthur Bridgman(1847 - 1928), The Diversion of an Assyrian King. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 by 92 in. 113 by 233.7 cm; signed F.A. Bridgman (lower left). Est. 400,000 - 600,000 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: W. S. Hobart, San Francisco

W. W. Crocker, Burlingame, California (and sold, Parke-Bernet Galleries, Inc., New York, November 12, 1970, lot 83,illustrated)

Bernard Crawford, New Jersey

Sale: Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, May 12, 1978, lot 235, illustrated

Coe Kerr Gallery, New York

Jerald Dillon Fessenden, New York (until 1985)

Sale: Sotheby's, New York, October 27, 1988, lot 50, illustrated

Private Collector, New York (acquired at the above sale)

EXHIBITED

Paris, Salon, 1878, no. 334 (as Divertissement d'un roi Assyrien)

London, Royal Academy, 1879, no. 441 (as A Royal Pastime at Nineveh)

New York, Samuel Putnam Avery Gallery (1880)

Boston, William and Everett Gallery (1880)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Second Annual Exhibition of the Philadelphia Society of Artists, 1880, p. 23, no. 375 (as A Royal Pastime at Nineveh)

New York, The American Art Gallery, Exhibition of Pictures and Studies by F.A. Bridgman, 1881, p. 21, no. 284 (as A Royal Pastime at Nineveh)

New York, Mr. Moore's American Art Gallery, Group Show

New York, Kirby's Gallery, October 1882

Possibly, London, The Fine Art Society, One Man Exhibition, no. 92 (as A Lesson in Archery)

Possibly, New York, Fifth Avenue Art Galleries, Catalogue of Mr. F.A. Bridgman - Exhibition of Pictures and Studies,1890, no. 24 (as Assyrian King Teaching his Son Archery)

New York, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, Adventure Inspiration: American Artists in Other Lands, 1988, pp. 86-7, no. 53, illustrated

LITERATURE: Lucy H. Hooper, “Art in Paris,” Art Journal (American ed.), n.s. 3, December 1877, p. 381

Mario Proth, Voyage au pays des peintres: Salon Universel de 1878, Paris, 1878, p. 47

“Art Preparations for the Coming Salon,” American Register, February 2, 1878, p. 4, col. 7

Lucy H. Hooper, “American Art in Paris,” Art Journal (American ed.), n.s. 4, March 1878, p. 90

Louis Énault, “Le Salon de 1878,” Figaro, Paris, May 25, 1878, p. 1, col. 4

Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science, and Art, vol. 46, no. 10, August 1878, p. 176

"American Painters - Winslow Homer and F.A. Bridgman," The Art Journal, vol. XVIII, 1879, p. 155

Henry Blackburn, ed., Academy Notes, London, 1879, p. 45

G. W. Sheldon, American Painters, New York, 1879, p. 152

Richard Whiteing, "Cham," Scribner's Monthly, vol XIX, no. 5, March 1880, p. 750

Montezuma, "My Note Book," The Art Amateur, vol. II, no. 5, April 1880, p. 91

"The Bridgman Collection," The Art Interchange, A Household Journal, vol. VI, no. 3, February 3, 1881, p. 25

Frederick Arthur Bridgman, "The Art of Two Worlds," The Studio and Musical Review, vol. I, no. 5, February 26, 1881, p. 1

Edward Strahan, "Frederick A. Bridgman," The Art Amateur, vol. IV, no. 4, March 1881, pp. 70-1

Edward Strahan, "Frederick A. Bridgman," Harper's New Monthly Magazine, vol. LXIII, no. 377, October 1881, p. 700

M. G. Rensselaer, "Frederick Arthur Bridgman," The American Art Review: A Journal Devoted to Practice, Theory,

History and Archaeology of Art, vol. II, 1881, p. 51

Valabrègue, Galeries contemporaine des illustrations françaises, 8, [1882], part 3, n.p.

"The Fine Arts: Art Notes," The Critic, vol. II, no. 47, October 21, 1882, p. 287

Edward Strahan, "F. A. Bridgman," Grand Peintres Français et Etrangers; ouvrage d'art public avec le concours

artistiques des Maîtres, vol. I, 1884, pp. 94-6

James Grant Wilson and John Fiske, ed., Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography, New York, 1888, vol. I, p.373

Walter Montgomery, ed., American Art and American Art Collections, Boston, 1889, vol. I, p. 183

"Famous Paintings Owned on the West Coast, VII: Bridgman's 'Diversions of an Assyrian King', owned by the Hobart Estate," Overland Monthly, vol. XXII, no. 127, July 1893, pp. 78-9, illustrated

Nouveau Larousse illustre, 1898, p. 101

William Howe Downes, Dictionary of American Biography, New York, 1930, vol II, p. 37

Ilene Susan Fort, "The Original Genre Paintings of Frederick Arthur Bridgman," unpublished paper, 1979, p. 5, 19, 20, illustrated

Lynne Thornton, Les Orientalistes: Peintres voyageurs 1828-1908, Paris, 1983, p. 172

Ilene Susan Fort, “Frederick Arthur Bridgman and the American Fascination with the Exotic Near East,” Ph.D.

NOTE: “In drawing and in general execution, the firm and practical hand of the master is everywhere visible [in The Diversion of an Assyrian King] . . . Gérôme himself might be proud to sign this page.” (Hooper, 1878)

These words, written at the time of this picture’s exhibition at the 1878 Paris Salon, summarized the opinion of many who encountered Frederick Arthur Bridgman’s art. A pupil of the great Orientalist painter Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), Bridgman had made his name one year earlier, winning a medal at the 1877 Salon and a place at the Paris Exposition Universelle with the archaeologically exacting Les Funerailles d’une momie (location unknown). Like thatwork, and true to Gérôme’s artistic principles, The Diversion of an Assyrian King was based on hundreds of sketches made abroad, an impressive personal collection of ancient artifacts, architectural fragments, and historical costumes, and countless hours of scholarly research. Bridgman’s many visits to the Louvre and the British Museum are evidenced by the precisely copied Assyrian wall reliefs in the background of the picture (it may, in fact, have been the celebrated lion hunt series of bas reliefs from Nimrod, ancient Nineveh, and Khorsabad, displayed since 1847 at these museums, that inspired the gripping subject of Bridgman’s work), while his assiduous study of large folios of engravings produced in the wake of the astonishing discoveries in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) of Austen Henry Layard (1817-1894) and Paul-Émile Botta (1802-1870) in the 1840s and the much-publicized efforts of the Englishman George Smith (1840-1876) to find ancient Assyrian accounts of the Deluge in the early 1870s, are reflected elsewhere in the composition.

The Diversion of an Assyrian King was the second of three highly acclaimed historical reconstructions that Bridgman painted in three consecutive years, and its progress was closely followed in the media. The light palette and vigorous brushwork in certain passages of the picture – trademarks of Bridgman’s maturing style – were widely commented upon by critics upon its debut, perhaps due to the uncommonness of these formal elements in academic history painting. Such idiosyncrasies, along with a fine balance between appealing spectacle and fearsome violence, are today what distinguish Bridgman’s theatrical tableaux from those of his mentor Gérôme (see Pollice Verso, 1872, Phoenix Art Museum), and from those of his peers, especially Bridgman’s friend Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), who also capitalized on contemporaries’ increasing fascination with the ancient world.

This catalogue note was written by Dr. Emily M. Weeks.

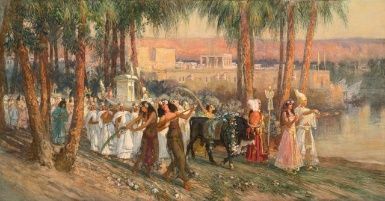

Frederick Arthur Bridgman(1847 - 1928), An Egyptian Procession. Oil on canvas, 33 by 63 in.. 83.7 by 160 cm; signed F.A. Bridgman and dated 1902 (lower left). Est. 200,000 - 300,000 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: Gerald P. Peters Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Pan Arabian Corporation

EXHIBITED: Paris, Salon, 1903, no. 264, as Procession en l'honneur d'Isis

New York, Society of American Artists, 1905, no. 233

LITERATURE: Ilene Susan Fort, “Frederick Arthur Bridgman and the American Fascination with the Exotic Near East,” Ph.D. diss., The City University of New York, 1990, pp. 405-6, 462 and 465, illustrated pl. 202, illustrated (as Egyptian Procession in Honor of Isis, with incorrect provenance)

Gerald M. Ackerman, American Orientalists, Paris, 1994, p. 48, illustrated p. 49 (as Procession in Honor of Isis)

NOTE: In 1903, Frederick Arthur Bridgman exhibited an Egyptian processional scene at the Paris Salon. Called Procession en l’honneur d’Isis and featuring an elaborately detailed Egyptian interior, it was later sent to the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis and the National Academy of Design in New York. Though the present whereabouts of that highly acclaimed canvas are not known, the variation presented here, painted in 1902, offers a clear indication of the reason for its fame.

An Egyptian Procession was one of several historical genre scenes produced late in Bridgman’s career, and one of four major processional scenes painted between 1879 and 1919. These works were closely related — both thematically and compositionally — to the artist’s historical reconstructions of the 1870s, the most famous of which were Les funerailles d’une momie (location unknown), exhibited at the 1877 Paris Salon, and the Procession du boeuf Apis of circa 1879 (Private Collection). The archaeological detail and exotic subject matter of these paintings immediately compelled comparisons to Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), Bridgman’s teacher and mentor in Paris during the 1860s. (Indeed, it was said that, “[W]hen translated into American, Gérôme means Frederic A. Bridgman,” The Perry Magazine, June 1904, 6.10, p. 421). Bridgman would later bring his own sensibility to Gérôme’s academic teachings, adopting a more naturalistic aesthetic emphasizing the opalescent colors and painterly brushwork seen here.

In the present work, the Graeco-Roman temple of Philae acts as a picturesque backdrop for an ancient Egyptian religious procession in honor of the goddess Isis (Navigium Isidis), to whom it was dedicated. The pharaoh who leads the way, incense-burner in hand, wears the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, indicating Isis’s universal worship, while the sacred Apis bull just behind him is adorned with flowers and a solar disk. (As the cow goddess, Isis was believed to be the mother of Apis.) Bridgman made sketches at the fabled site first in 1874 and again during his numerous subsequent visits to the region; these, combined with his diligent research into the manners and customs of the ancient Egyptians, allowed him to create a remarkably vibrant — if ultimately over-embellished — scene of ritual and revel.

It is worth noting that the setting of Bridgman’s picture would have been particularly resonant in 1902 – this was the year that the Aswan Low Dam was built by the British, threatening the monuments at Philae by changing the rise and fall of the surrounding Nile River.

This catalogue note was written by Dr. Emily M. Weeks.

Consigned by a private California collector is Horses at the Ford – Persia by Edwin Lord Weeks who, like Frederick Arthur Bridgman, is among the most important American Orientalist painters of the late 19th century (est. $250/350,000). This large, expansive composition shows the artist’s own caravan crossing a stream in the vast Persian desert somewhere between Tabreez and Teheran in the fall of 1892. The finished work was painted in the artist’s studio around 1894-5, shortly after his return to Paris.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F13%2F89%2F119589%2F126209480_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F88%2F53%2F119589%2F126057534_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F92%2F94%2F119589%2F93970540_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F37%2F38%2F119589%2F73692413_o.jpg)