Riotous Baroque: From Cattelan to Zurbarán at Guggenheim Bilbao

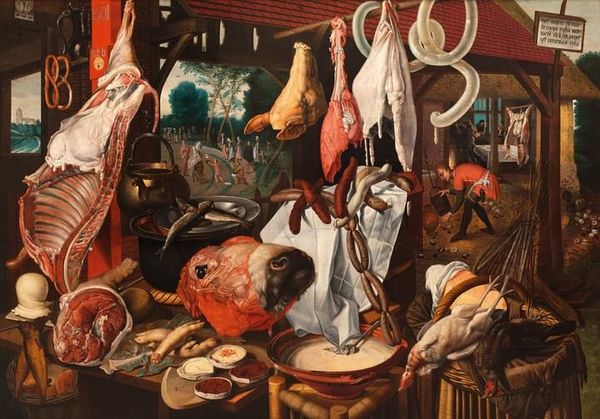

Pieter Aertsen (1507/08-1575), The carnage, 1551-1555. Collection Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht

BILBAO.- Co-organized by Kunsthaus Zürich and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Riotous Baroque. From Cattelan to Zurbarán – Tributes to Precarious Vitality strikes up a dialogue between 17th-century artworks and contemporary pieces in an attempt to extricate the concept of the Baroque from its conventional stylistic pigeonhole, moving away from clichés such as pomp, rich ornament, or gold and instead focusing on the Baroque as a "tribute to precarious vitality": the riotous yet uncertain nature of existence.

The show juxtaposes works by great 17th-century masters such as Pieter Aertsen, Giovanni Battista Langetti, Alessandro Magnasco, José de Ribera, Jan Steen, David Teniers the Younger, Simon Vouet, and Francisco de Zurbarán with that of renowned contemporary creators like Maurizio Cattelan, Robert Crumb, Urs Fischer, Glenn Brown, Tobias Madison, Paul McCarthy, and Cindy Sherman, among others. Rather than drawing superficial thematic and formal analogies, the exhibition attempts to enable the two realities, with all their differences and affinities, to collide, cross-fertilize and permeate each other, inviting the audience to see them in a whole new light.

In the words of Bice Curiger, curator of the exhibition, Riotous Baroque does not seek to "host a festival of masterpieces", nor does it attempt to "proclaim a neo-Baroque stylistic tendency"; rather, it aims to bring an art separated from us by several centuries into the world of the comprehensible, the world of experience: "In our age of massive revolutions in visual and communications media, revisiting an epoch that celebrated the visible and the sense of sight as a popular allegorical motif is both pleasurable and meaningful. The impulses of the present day will perhaps open up new ways for us to look at old art."

More than one hundred works fill the third-floor galleries of the Museum, with an arrangement inspired by cinematographic montage techniques that invites us to look back at history from a contemporary perspective, exploring a wide range of popular Baroque themes such as earthiness, coarseness, religiosity, and sensuality, the grotesque, the burlesque, and the virile from multiple angles.

In addition to pieces from Kunsthaus Zürich, the show features loans from some of Europe's leading Old Masters museums, such as the Museo de Bellas Artes of Bilbao, the Prado Museum, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and the Städel Museum in Frankfurt. The exhibition also includes a number of invaluable works from private collections.

The Bucolic and the Comical

The exhibition opens in the classical galleries with a series of works that reflect vice, dissoluteness, sinfulness, and passion, a cheerful, carefree thematic repertoire developed in the 17th century to cater to the tastes of the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, a new class of buyers that emerged from the ranks of prosperous city merchants.

Bucolic, comical scenes that depict an everyday reality filled with sensual and carnal temptations, such as Wedding Feast in a Farmer's Tavern (ca. 1665) by Jan Steen and Still Life with a Pig (La Porchetta) by José de Ribera, alternate with images of the poverty, obscenity and violence prevalent in the society of that era, as in Adriaen Brouwer's Tussling Farmers by a Barrel (1625–1638). In these works, the artists depicted worldly motifs with all their nuances which simultaneously attempt to teach a moral lesson that is not immediately apparent.

Juergen Teller, Paradis XII, 2009. Courtesy the artist and the Lehmann Maupin Gallery

This same section includes a work by Juergen Teller in which two of his female friends are photographed as they stroll naked through the empty halls of the Louvre, posing before the Mona Lis a and the Borghese or Sleeping Hermaphroditus . The convergence of life with art—and vice versa—is slightly unsettling and surreal in this publicly practiced intimacy.

An entirely different reality is presented in the photographs taken by Boris Mikhailov on the fringes of modern post-Soviet society, a community overrun by Western consumerism that now finds itself in harried, oppressive circumstances. The existential tenor of these images makes us think of the "life excluded from the art space", alluding to a kind of existence undoubtedly led by many people on our planet.

The same space contains Dana Schutz's piece How We Would Dance (2007) which, according to the artist herself, combines the fantastical and the reflective by evoking the upside-down saint in Caravaggio's Crucifixion of Saint Peter with a figure in her painting that appears to be falling backwards.

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1624), Hercules diverted the river Alpheus, 1634. Museo del Prado, Madrid

Mythology and the Glorification of Manliness

In a patriarchal society, ruling houses deliberately invoked mythology or the heroes of Antiquity to legitimize their own lineage and power. Thus, the figure of Hercules portrayed by Francisco de Zurbarán symbolized not only the personification of virility but also the ideal of a virtuous sovereign. Cautionary visual depictions of human vice and models of a virtuous lifestyle all revolved around a world of men. Homages to feminine charms, almost always subtle and discreet, stood in contrast to paeans to male virility and heroism.

The tale of Susannah and the Elders (ca. 1745-50), which shows the sexual violence done to a lovely young woman by two lecherous old men, is illustrated in an eponymous painting by Francesco Capella. This particular story was a popular motif because it satisfied buyers' voyeuristic desires in a morally unrestrained context. We come across Susannah again in Glenn Brown's Nigger of the World (2011), but here she is headless and her body covered in lacerations: she has lost her attractiveness, and the leering old men have also disappeared.

The highly disturbing picture by Christiaen van Couwenbergh, The Rape of the Negress (1632), takes a similar direction, allowing us to witness the crude scene of a black female slave being raped by three white men.

A work from the Problem Paintings series by Urs Fischer likewise immerses us in the complexity of the artistic representation of sexual relations. The artist superimposes fruits, vegetables, tools and other objects on the faces of Hollywood actors, in a personal exploration of the classic genres of art history such as the portrait and the still life.

In the case of Maurizio Cattelan, this artist frequently infiltrates the art space with signs of life that are usually excluded from it. For example, his Untitled (2007) shows two stuffed dogs closely watching a small chick, which seem to represent the Baroque idea that vitality can also be a sign of the precariousness of life, of its fragile, ephemeral nature.

Maurizio Cattelan (1960 -) Untitled, 2007-Dogs and dissected and expanded polyurethane. Chick-Dimensions variable, Installation view: Maurizio Cattelan, Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria, Feb. 2 March 24, 2008. Museo del Prado, Madrid. ParticularFoto Collection, Markus File TretterCortesia Maurizio Cattelan

The Burlesque and the Grotesque

This period also had a taste for depictions of coarse, impulsive behavior that flouted conventions and of the anomalous, the ugly and the discordant, in direct opposition to sublime classical harmony. Deformity and exaggeration were tools that artists used to address themes like the body and sexuality with detachment.

Juan Carreño de Miranda's portrait of the naked body of Eugenia Martínez Vallejo reveals to us a "shemonster", which the artist rendered both clothed and nude. The Baroque taste for the bizarre, for bruttezza , is also apparent in other works, such as Faustino Bocchi's Burlesque Scene or The Crazy Lovers by Bartolomeo Passerotti.

Certain contemporary works convey the modern reality of a world drowning in excess and hyperconsumerism, and a case in point is Under Sided, the sculptural theatre in which Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch's video installation Temp Stop (2009-10) is displayed, offering a glimpse of a darkly obsessive youth culture.

One of the large petal-shaped galleries in the building designed by Frank Gehry contains works on mythological themes that draw us into a rich universe of literary allusions, fantasy and eroticism, such as Satyrs Taking Sleeping Venus by Surprise (ca. 1925) by Nicolas Poussin and Allegorical Scene (1680–1690) by Dominicus van Wijnen.

Nicolas Poussin, Satyrs Taking Sleeping Venus by Surprise, ca. 1625 (detail). Kunsthaus Zürich

In Simon Vouet's painting The Rape of Europe (ca. 1640), the depiction of carnal lust is lent a humorous note by the bull's expression, with its lascivious, lolling tongue and bulging eyes staring at Europa's bared breast with unconcealed desire.

Simon Vouet (1590? 1649), The Rape of Europa, ca. 1640 © Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

Lasciviousness and crudeness are also present in Urs Fischer's irreverent piece entitled Noisette (2009), in which a highly realistic silicone tongue, activated by motion sensors, pokes out through a hole in the wall of the Museum and waggles gently before the eyes of the surprised visitors before retreating into the recess once more. This work is in keeping with the social conventions of the northern European Baroque, when sticking out one's tongue was considered a bawdy, rude, irreverent, rule-breaking gesture, just as it is today. However, Noisette also conveys something subtler, animating the art space and causing life to protrude from the centre of a lifeless wall.

Caravaggio and Darkness

The show continues with a series of paintings that employ the chiaroscuro technique with which Caravaggio revolutionized the art world in the 17th century, creating a heightened sense of drama that focuses on the sacred and the profane, daily life and sensual corporeality. This trend spread across Europe and was particularly popular in the north, primarily thanks to the Caravaggisti of the Utrecht School. The sculptural voluptuousness of Saint Sebastian Attended by Saint Irene and Her Maid (ca. 1615–1621) by Dirck van Baburen offers a clear example of religious emotionality and humanity. Caravaggio's influence was particularly strong among Spanish painters. In the daring composition Saint Sebastian Tended by the Holy Women (ca. 1621), José de Ribera, whose realism influenced the development of the Italian Baroque in Rome and Naples, found inspiration in Caravaggio's use of light and revisited the theme of the martyrdom of St. Sebastian with a direct, elementary pictorial style.

José de Ribera (1591-1652), San Sebastian healed by the holy women, ca. 1621. Museum of Fine Arts in Bilbao.

Glenn Brown's Carnival (2011) also uses lighting—in this case a powerful blue light to heighten the dramatic appeal of a horse head measuring more than 3 meters. As we move closer to the picture, the brushstrokes blend together in an orderly tangle of disturbing lines and patches of color that is both surprising and unsettling.

In the Late Baroque, themes related to night-time and darkness took on a new eeriness in the gloomy visions of Alessandro Magnasco and his rapid, nervous painting populated by shadowy figures of monks and brigands (Monks by a Fire, ca. 1725). In Court Scene (ca. 1710-20), Magnasco depicted a prison interrogation tableau that conveys a sense of the full dread and horror inspired by the Inquisition, which ordered people to be tortured in the name of the Lord. The counterpoint to self-flagellation was the carnival, which served as an escape valve, a legally sanctioned opportunity to contravene the established order, as we see in Pieter van Laer's Carnival Celebration at an Inn (ca. 1635).

Representations of witches and the torments suffered by St. Anthony express the phantasmagoria of temptation. In the mysterious paintings of Monsù Desiderio, considered an early forerunner of Surrealism, we see classical architectural structures, almost always devoid of human presence, that topple, explode or blaze in the spectral glow of the night.

Alongside these we find the raw, precarious, aggressive interventions of Oscar Tuazon, with their poetic allusions to both the history of modern sculpture and the counterculture of the 1970s, as well as to other speculative and utopian ideas related to housing, survival strategies and shelter. In Numbers (2012), Tuazon created a composite walk-in sculpture that refers to the modules which, in the United States, represent the minimum dimensions for small spaces like shower stalls or telephone booths permitted by law.

Vanitas , or the Manifestation of Excess

The final section of the show features a variety of allegories and portraits, as well as works that address a theme familiar since Antiquity and highly popular during the Baroque: the vanitas . In the 17th century, the presence of wars and catastrophes meant that death was ubiquitous, a fact that was reflected in countless symbols such as skulls—Vanitas Still Life with Skull, Wax Taper and Pocket Sundial (ca. 1620) by a German master—and in pictorial motifs like the ships tossed on stormy seas so eloquently rendered by Jacob van Ruisdael.

In this context, the still life acquired special significance. Cut pieces of fruit and wild game carcasses are depicted with erotic ambiguity, while the splendidly laid tables, luxuriant floral arrangements and the beauty of exotic artifacts remind us that transience and decay is our true and ultimate fate, as in David de Coninck's Still Life with Flowers, Fruit, and Small Monkey (ca. 1685).

The four hyper-realistic paintings (enamel on aluminum) by Marilyn Minter displayed in this same gallery, delightful and disturbing in equal measure, may also be an attempt to reflect excess and exuberance. An enormous baby happily plays in the midst of silver paint, representing the human quest for pleasure, expensive high heels splash in muddy puddles, and a woman's mouth, caught halfway between a mischievous smile and a grimace, drips and glistens. These images bear an excessive celebration of the surface, the visible and what has been called the ‘pathology of glamour’.

Art's closeness to the crude reality of life is also addressed in Diana Thater's large video installation on the theme of Chernobyl and the disaster that occurred on April 26, 1986, in Reactor 4 of the nuclear power plant on the outskirts of the Ukrainian city of Prypiat, now one of the world's most heavily contaminated regions. Thater's film conveys the eeriness, gloom and menace of this abandoned site. The atmosphere of ruin is pervasive, and yet there is something curiously romantic about the desolate landscape. Thater shoots the rubble and detritus of the disaster while simultaneously expressing her awe at the extraordinary power of nature.

Diana Thater (1962 -) Chernobyl (Chernobyl), 2010-Installation. Image courtesy of Hauser & Wirt

This exhibition takes a different and singular look at art history, displaying the art of centuries past alongside selected works by contemporary artists and thereby juxtaposing two distinct realities which, according to the curator, "are mutually enriched by their clash, heightening their charge and interrupting the linearity of conventional narrative techniques".

Albert Oehlen (1954 -) FM 18, 2008. Loan artist © VEGAP, Bilbao, 2013

Glenn Brown (1966 -), Happiness in the pocket (The Happiness in One's Pocket), 2012. Collection of the artist, Courtesy Gagosian Gallery © VEGAP, Bilbao, 2013

Urs Fischer (1973 -) Paint problem (Problem Painting), 2012. Gift of the artist © Photo: Mats Nordman

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240423%2Fob_981d5f_h22891-l367411650-original.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F96%2F49%2F119589%2F129580191_o.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F40%2F31%2F119589%2F128509350_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F92%2F57%2F119589%2F127733091_o.jpg)