Buddhist Masterworks at Asian Art Museum

Seated Buddha, 338. China, Later Zhao dynasty (319–350). Gilded bronze. The Avery Brundage Collection, B60B1034. Asian Art Museum © 2014 Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture

This Buddha has a unique status among Buddhas in China.

It bears an inscription on the back that is equivalent to the year 338. This is the earliest date inscribed on any Buddha sculpture from China, anywhere in the world.

The Buddha was completely covered in gold except for the head, which was probably painted dark blue or black.

While the sculpture is almost completely intact, there are some elements missing. On the back of the head is a square protrusion with a round hole in the middle. It suggests that something was once attached to the back of the Buddha, most likely an umbrella. On the front there are three holes. These most likely would have supported a pair of guardian lions, one on each side, with a lotus in the center.

Around the year 310, Northern China fell under the control of non-Chinese invaders called the Jie—Indo-Iranian people who came from Central Asia. The Jie used the spread of Buddhism to establish their right to rule the Chinese population of the area they had conquered.

Standing Brahma (Bonten). Japan, Nara period (710–794). One of a pair; hollow dry lacquer. The Avery Brundage Collection, B65S13. Asian Art Museum © 2014 Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture

Standing Brahma (Bonten) (detail). Japan, Nara period (710–794). One of a pair; hollow dry lacquer. The Avery Brundage Collection, B65S13. Asian Art Museum © 2014 Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture

Standing Indra (Taishakuten). Japan, Nara period (710–794). One of a pair; hollow dry lacquer. The Avery Brundage Collection, B65S12. Asian Art Museum © 2014 Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture

Standing Indra (Taishakuten) (detail). Japan, Nara period (710–794). One of a pair; hollow dry lacquer. The Avery Brundage Collection, B65S12. Asian Art Museum © 2014 Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture

Brahma and Indra, or Bonten and Taishakuten as they are known in Japanese, were Hindu deities brought into Buddhism as attendants of the Buddha or of bodhisattvas.

These two sculptures were created for Kofukuji, one of the most important temples in Nara, where the capital of Japan was located in the 700s.

A Rare Technique

This pair is important for many reasons, one being that the sculptures were made using the hollow dry lacquer technique, an ancient method that produced lightweight, portable statues. It was only used in Japan for about 100 years.

The technique begins with a clay core. Since these figures are almost life-sized, the core would have been built on wooden scaffolding. Once the clay core is built, layers of textile are dipped in Asian lacquer, called urushi, and applied to the figure in layers.

Once the lacquered textile is dry, the figure is cut open, usually at the back, and the clay core is scraped out. The original wooden support is also removed and a new one is added to the interior for reinforcement. The panel that was cut away is replaced, and finishing layers are applied to the now hollow figure. Once dried, it can be painted and gilded as desired.

A Historical Mystery

The Asian Art Museum’s Bonten and Taishakuten are the only large-scale, matched Japanese hollow dry lacquer sculptures from the Nara period in a U.S. collection. Even in Japan, sculptures like these are extremely rare and most have been designated as National Treasures or Important

These statues were among a number of items sold from Kofukuji in 1906. Photographs of the temple’s contents were taken at that time and these figures can be seen in one of the photographs. However, in the photograph the figures are missing their hands and feet, and there is damage to one head, and the other head is missing . By the time the museum’s founding collector, Avery Brundage, purchased them in the early 1960s, the figures were complete. So the question ever since then has been: how much of each of these figures is restoration, and how much is original?

Many historians believed that the restored parts were 20th-century replacements, making the statues less important. But research conducted in 2012 by a team of Japanese scholars and the Asian Art Museum indicates that many of those parts are original.

X-rays taken of the statues revealed a wooden framework inside the statues, as well as both ancient and modern nails used in the construction and repair of the figures.

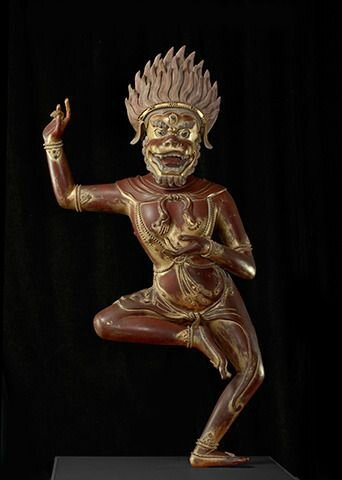

The Buddhist deity Simhavaktra Dakini. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), reign of the Qianlong emperor (1736–1795). Dry lacquer inlaid with semiprecious stones. The Avery Brundage Collection, B60S600. Asian Art Museum © 2014 Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture

The Buddhist deity Simhavaktra Dakini (detail). China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), reign of the Qianlong emperor (1736–1795). Dry lacquer inlaid with semiprecious stones. The Avery Brundage Collection, Asian Art Museum © 2014 Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture

Simhavaktra means “lion faced” or “lion headed,” and a dakini is a “sky-walker”—an inhabitant of the realm of the sky in the mind.

Created in China during the 1700s, Simhavaktra’s style nonetheless reflects strong Tibetan influence. Such cross-cultural influences have historically been common in Himalayan forms of Buddhism.

Simhavaktra balances deftly, despite her apparently awkward posture. To successfully create a sculpture of this type, extremely high levels of artistic skill were necessary. Indeed, Simhavaktra is one of only two comparable sculptures still extant in the world.

Symbolic details abound on Simhavaktra, but perhaps her most startling feature is the dakini’s ferocious appearance.

The Dakini in Tibetan Buddhism

With her flaming hair and human skin cape, Simhavaktra might seem violent and scary. But here she is a force for good; the dakini’s fierce appearance symbolizes her power to overcome obstacles to enlightenment, such as lust, anger or ignorance.

Every aspect of the statue conveys deep meaning. For example, her flaming hair symbolizes the blazing fire of her wisdom. The human skin cape symbolizes the stripping away of the veil of illusion from perception. Even Simhavaktra’s jewelry is symbolic. Her two bracelets, two armlets and necklace symbolize the Five Buddhas who preside simultaneously over the cardinal directions of the cosmos (four directions plus central axis) and the negative components of ordinary human psychology (lust, hatred, delusion, pride and jealousy). If you look at Simhavaktra’s forehead, you’ll see a wonderful, gleaming third eye that indicates she’s able to see past these same negative forces.

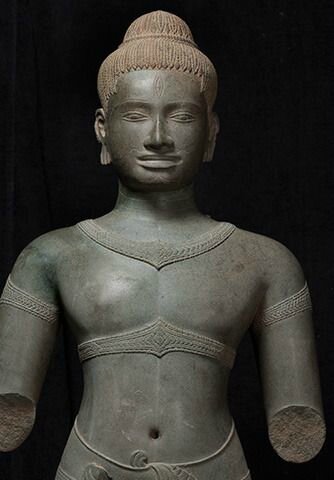

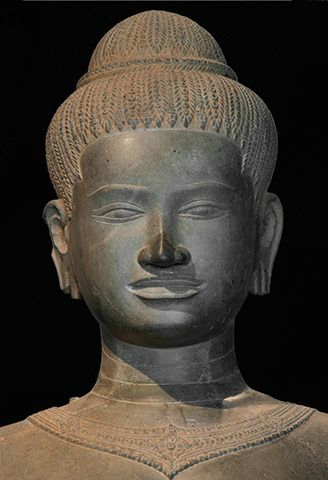

The Hindu deities Shiva and Parvati, 1000–1100. Cambodia. Sandstone. The Avery Brundage Collection, B66S2 and B66S3. Asian Art Museum © 2014 Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture

The Hindu deity Shiva (detail), 1000–1100. Cambodia. One of a pair; sandstone. The Avery Brundage Collection, B66S2. Asian Art Museum © 2014 Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture

The Hindu deity Parvati (detail), 1000–1100. Cambodia. One of a pair; sandstone. The Avery Brundage Collection, B66S3. Asian Art Museum © 2014 Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture

Apart from their damaged limbs, these 1,000-year-old Cambodian sculptures survive in excellent condition, and the fact that they have remained together makes them rare.

It was typical for artists of this period to contrast large smooth surfaces with highly textured areas. In addition to the jewelry, look at the pleats carved into their lower garments. These figures also reflect a change from the formal way deities had been portrayed earlier, when their might and godly distance from mortals was emphasized. Instead, here they appear younger and more accessible, and have a sense of tenderness. You may be reminded of ancient Greek deities like Apollo or Aphrodite, whose physical beauty and approachability are part of what attract us to them.

Religious Use

Shiva has powerful creative and destructive capabilities. He’s associated with fertility but also with destruction. Shiva was usually the primary deity worshipped in the great temples of ancient Cambodia. His wife, Parvati, who was associated with peaceful stability, was worshipped as a deity in her own right. Pairing them suggests the unity and wholeness of the principles they represent.

The Buddha triumphing over Mara, 900–1000. India. Stone. The Avery Brundage Collection, B60S598. Asian Art Museum © 2014 Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture

The main figure in this stone sculpture from the 900s shows many characteristic features of images of the Buddha.

The lump on the top of his head is sometimes said to indicate extraordinary wisdom. He is represented in a posture portrayed widely, seated with his legs crossed in a meditative position.

The twisted garland of beads behind the Buddha’s head represents his halo, a symbol of radiance. Around the inside of this halo, incised in low relief, is a standard formulation of a basic Buddhist belief:

“The Buddha has explained the cause of all things that arise from a cause. He, the great monk, has also explained their cessation.”

Here we see elements that tell us we’re in the presence of the Buddha as he was on the threshold of achieving enlightenment. Above his head are branches of heart-shaped leaves. They indicate the sacred bodhi tree, under which he is said to have attained enlightenment some 2,500 years ago.

His right hand reaches downward to touch the pedestal—symbolizing the ground on which he sat. Buddha images seated with the right hand in this earth-touching gesture memorialize the victory of the Buddha-to-be over the demon Mara, an embodiment of delusion and uncontrolled passions.

After many lifetimes of spiritual and intellectual preparation, while the Buddha-to-be sat in meditation under the bodhi tree, he and Mara repeatedly challenged each other’s power and accomplishments. Mara approached at the head of a monstrous army, determined to stop the Buddha’s enlightenment. The Buddha stretched out his right hand, calling out to the earth to witness his right to attain Buddhahood. The mighty earth thundered, “I bear you witness with a hundred thousand roars.” And Mara’s followers fled.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F06%2F39%2F119589%2F129007933_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F83%2F41%2F119589%2F128989180_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F65%2F49%2F119589%2F128551133_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F78%2F119589%2F126903004_o.jpg)