Sotheby's to offer one of the greatest portraits by Gustav Klimt to come to auction

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Gertrud Loew -Gertha Felsőványi, signed Gustav Klimt and dated 1902 (upper left), oil on canvas, 149.5 by 45cm., 58 7/8 by 17 3/4 in. Painted in 1902.. Estimate: £12-18 million / $18.5-27.7 million / €16.8-25.3 million. Photo: Sotheby's

LONDON.- Sotheby’s London today announces that Gustav Klimt’s extraordinarily beautiful and captivating portrait Bildnis Gertrud Loew of 1902 will be offered for sale in its 24th June Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale following a settlement between the Felsöványi family and The Gustav Klimt | Wien 1900-Privatstiftung (Klimt Foundation). The painting (est. £12-18 million / $18.5-27.7 million / €16.8-25.3 million) depicts the ethereal figure of Gertrud Loew, later known by her married name Gertha Felsöványi, a member of fin-de-siècle Viennese society, wreathed in diaphanous folds of gossamer fabric.

Helena Newman, Sotheby’s Co-Head of Impressionist & Modern Art Worldwide said: “Gustav Klimt’s exquisite and ingenious representations of women have led to him become the most celebrated painter of the female portrait of the early 20th Century. Bildnis Gertrud Loew, from a crucial period in the artist’s career, is one his finest portraits to appear at auction in over twenty years.”

Gertrud Felsöványi’s granddaughter, commenting on behalf of the family heirs, said: “This portrait portrays the brave and determined nature of my grandmother. Her strength of character and beauty lives on in this visual embodiment. My father, Anthony Felsöványi, last saw this painting in June 1938 when he left the family home for the last time to depart for America. At that time my grandmother had been advised to leave her family home to live in a less grand home to try to avoid the attention of the Nazis, given her Jewish ancestry. Eventually, under duress, in 1939 she left Vienna altogether to join my father in America, having left all of her belongings behind - including this painting. Her home had been taken over as a Nazi headquarters and she had left her valuable belongings with friends and acquaintances. After the war, she never returned to Vienna. Only my father’s sister did, with the hope of retrieving some of their belongings, but to no avail. My father said that my grandmother never again mentioned the painting or the valuable belongings she had left behind.

“My father recalled that throughout his childhood the painting was displayed in the entrance hall of their family home. It was displayed prominently on a stand rather than hung on the wall, and faced out to the gardens. After he had left Vienna, my father hung a reproduction of the Klimt portrait of his mother in his home in America.

While sadly my father is no longer alive, having died two years ago aged ninety-eight, this settlement would have meant a great deal to him, as it does to me and the other family heirs with whom this settlement has been agreed. Before his death my father had wanted to thank Mrs Ucicky for her longstanding desire to work towards this settlement, and our family wishes to thank her as well as the researchers and others involved in bringing about this resolution.”

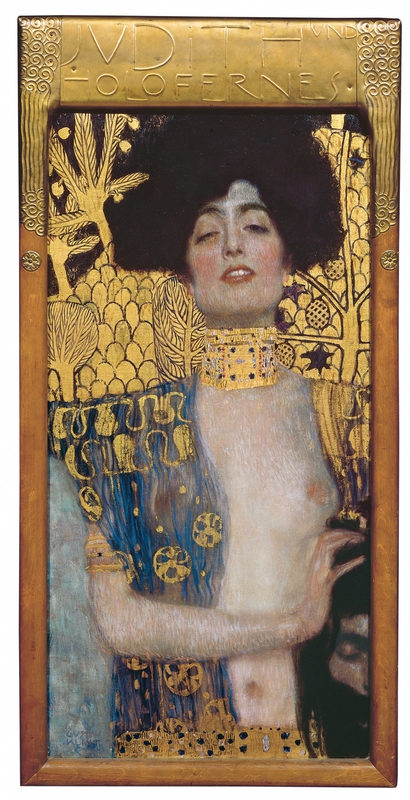

Bildnis Gertrud Loew was commissioned by Gertrud’s father Dr Anton Loew, at the time one of the most celebrated physicians in Vienna. The Loew family lived in a palatial residence adjoining the Sanitorium Loew – the largest and grandest private sanatorium in Vienna where a number of important fin-de-siècle figures were treated, including Gustav Mahler and Gustav Klimt, as well as Ludwig Wittgenstein. The success of the Sanitorium enabled Anton Loew to acquire some of the greatest masterpieces of the time, including Ferdinand Hodler’s Der Auserwählte (now in the Kunstmuseum, Bern) and a further important work by Gustav Klimt, Judith I (now housed in the Belvedere, Vienna). He had also commissioned the artist Koloman Moser to design Gertrud and her first husband’s apartment in the Wiener Werkstätte style, but following Anton’s death Gertrud moved back to the family’s residence where she continued to run the Sanatorium. When the Nazis arrived in Vienna she came under increasing pressure due to her Jewish ancestry, and in early 1939 reluctantly agreed to leave Vienna for exile in the United States, leaving the entire Felsöványi art collection behind. When Gertrud’s daughter, Maria, returned to Vienna after the war to reclaim her family’s property she discovered that it had all been sold by her mother’s friend – herself under duress by persecution - and the Felsöványi family was not able to retrieve a single work of art.

Untraceable by the Felsöványi family, by then Bildnis Gertrud Loew had been acquired by Gustav Ucicky, one of Gustav Klimt’s sons by Maria Ucicka who had modelled for the artist. Gustav Ucicky was a film director who rose to prominence during the Weimar Republic. He acquired a considerable number of works by his father, which he left to his wife Ursula after his death in 1961. In 2013 Ursula Ucicky established Gustav Klimt | Wien 1900-Privatstiftung which houses this collection of works and is also a non-profit cultural, art historical, scientific and educational centre. In addition to aiming to preserve and research the life and oeuvre of Gustav Klimt, Ursula Ucicky wished to research the history of the acquisition of the artworks in the collection, enlisting notable provenance experts to carry out the research. Following extensive research, a settlement between the Felsöványi family and the Klimt Foundation was reached under the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art and an agreement that Bildnis Gertrud Loew will be offered for sale.

Commenting on the sale, Peter Weinhäupl, Chair of the Board of Directors of The Gustav Klimt | Wien 1900-Privatstiftung (Klimt Foundation), said: “Mrs Ucicky and the Klimt Foundation are happy and grateful that a just and fair settlement was reached with the heirs of the Felsöványi family on the basis of the Washington Conference Principles and in accordance with our Foundation’s charter.”

A photograph of Gertrud Felsőványi, circa 1902.

Gertha Felsöványi

Gertrud Loew, known as Gertha, was nineteen years old when she was painted by Gustav Klimt in 1902. Dr Anton Loew had become one of the first benefactors of the Secession movement, co-sponsoring the building of the Secession, and in addition to works by Klimt, Hodler and Segantini, he collected antiques, baroque and renaissance art.

In 1903 Gertha married Hans Eisler von Terramare in the Minoritenkirche in Vienna. After the early death of the couple’s only daughter Gertrude, the marriage fell apart. Gertha moved back into the family residence next to the Sanitorium and took over the running of the Sanatorium after Dr Anton Loew’s death in 1907. In 1912 she married the Hungarian industrialist Elemér Baruch von Felsöványi with whom she had three children. In November 1923 her husband caught pneumonia returning from a nightclub without an overcoat and died a few days later.

When the Nazis arrived in Vienna, Gertha was encouraged by her lawyer to leave her home and move into more modest accommodation, and then under increasing duress she reluctantly left in 1939, entrusting her artworks to a friend for safekeeping. Although her son Anthony was already living in America, Gertha was denied an entry visa and was not allowed to disembark when she docked in New York harbour; it was only through the intercession of Eleanor Roosevelt that she was allowed a day pass to spend Christmas 1939 with her son. She continued her journey to Colombia and spent time as a French teacher in Barranquilla while she waited for the grant of a US visa. In June 1940 she arrived in the USA where she started a new life, working nightshifts. When Gertha’s daughter Maria returned to Vienna after the war to reclaim her family’s property she discovered the fate of her family’s collection. Having learned about the losses of her father’s legacy, Gertha Felsöványi never returned to Austria. She died in Menlo Park, California in March 1964 at the age of 80.

A Portrait Painter of International Acclaim

Bildnis Gertrud Loew was exhibited on numerous occasions during the artist’s lifetime, both in Austria and Germany. The portrait was first exhibited in the Wiener Secession's Klimt exhibition in 1903 where it was reviewed by the great Viennese art critic, Ludwig von Hevesi, and described as ‘. . . the most sweet-scented poetry the palette is able to create.’ Klimt’s foundation of the Secession and its association with private supporters allowed him to cultivate prospective commissions as well as exhibitions on a large scale, in a manner rarely afforded to artists before him. The growth of private patronage from the haute-bourgeoisie was needed to replace the large-scale commissions from the State and city of Vienna which previously supported many of Austria’s artists.

Gustav Klimt’s exquisite and ingenious representations of women have led to him become the most celebrated painter of the female portrait of the early 20th Century. Bildnis Gertrud Loew, painted in 1902, is an extraordinarily beautiful and captivating work from a crucial period in the artist’s career. Wreathed in diaphanous folds of gossamer fine white and lilac cloths, the sitter’s delicate features are composed into an expression of dreamy repose and gentleness, animated only by points of reflected light in her eyes. Klimt’s vertically inclined composition helps to enhance the figure’s somnambulant detachment by removing all extraneous details.

Discussing the narrow format and other compositional elements of the present work, Alfred Weidinger comments: ‘In a way similar to the portrait of Serena Lederer [fig. 1], Klimt here uses a strikingly narrow vertical format for his likeness of the nineteen-year-old girl – except that here the format is even narrower. Along the right-hand side, a portion of her shawl is cut off by the edge of the picture. This elongates the figure and reduces her distance from the viewer. The narrow format seems to have been inspired by Japanese art. Even the colour accents set by Klimt by means of his signet and the ornament in the area of the upper left of the picture are reminiscent of Japanese woodblock prints’ (A. Weidinger, op. cit., p. 275). A passion for Japanese and Chinese art had gripped European intellectuals since the latter half of the 19th century. Numerous illustrated journals, exhibitions, recently opened museums and burgeoning private collections fuelled its integration with the avant-garde artistic practises of the day. Klimt’s own devotion to Orientalism is evident in a number of works from 1900 onwards, culminating in the boldly experimental inclusion of Asian motifs in his later portraits of Friederike Maria Beer and Elisabeth Lederer.

fig. 1. Gustav Klimt, Bildnis Serena Lederer, 1899, oil on canvas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The symbolist treatment of the female portrait was to be one of Klimt’s definitive developments at the start of the 20th Century. The virginal purity of the tonalities and ethereal atmosphere evoked in Bildnis Gertrud Loew serve to elevate the work from its primary biographical purpose and engage with allegorical themes of youth and feminine purity. Quoting from another source, Doris H. Lehmann argues: ‘Each of Klimt’s female portraits is more than just a representation of his model. As Thomas Zaunschirm has written: Fundamentally, Klimt was less a portraitist than a painter who used female portraits for the purpose of his own allegories”’ (D. H. Lehmann in Facing the Modern. The Portrait in Vienna 1900 (exhibition catalogue), National Gallery, London, 2013, p. 99). This effect was achieved in part by the impressionistic brushwork which only loosely defined a sense of space in the picture, and was also due to the lack of topographical reference – a conceit that was a particular feature of Klimt’s portraits until the introduction of geometrical forms in the portrait of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s sister Bildnis Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein of 1905, now in the Neue Pinakothek in Munich (fig. 2).

fig. 2. Gustav Klimt, Bildnis Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein, 1905, oil on canvas, Neue Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.

fig. 3. Gustav Klimt, Bildnis Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann, 1900-01, oil on canvas. Sold: Sotheby’s, London, 31st March 1987

fig. 4. Gustav Klimt, Bildnis Hermione Gallia, 1903-04, oil on canvas, The National Gallery, London

Toward the turn of the century Klimt began to employ a near monochromatic palette in his portraiture. This development drew his work in line with the chromatic experimentations James Abbot McNeill Whistler undertook in London. The similarities between the two artists’ work was well noted at the time and has subsequently been seen as an important element of Klimt’s development as a painter. Discussing Whistler and Klimt, Manu von Miller writes: ‘Both were interested in deploying an increasingly abstract form of portrayal in order to convey the underlying meaning and elevate if to a plane of detachment and timelessness. Whistler did so by using colour as a means of expression, creating a lyrical atmosphere through the graduation of colours and the soft fluidity of contours. Klimt breaks the surface up into a densely woven tapestry of ornament, conjuring sublime surface effects by playing with the contrast between abstract ornamental forms and the highly erotic sensuality of the figures. Both these artists use a visual syntax that evokes a vague dreamlike fantasy world full of profound and exalted passions beyond the bounds of modern reality’ (M. von Miller in A. Weidinger (ed.), op. cit., pp. 69-70). In portraits such as Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl (fig. 6), Whistler’s use of limited palettes accord with Klimt’s own use a few decades later. These simplified tonal ranges enabled Klimt and Whistler to enhance the stylisation whilst retaining the elegant allure of the formal portrait style. Furthermore, these daring painters assumed a technique which had long been considered the academic painters' finest attribute - the virtuosic application of ‘white-on-white’ paint.

fig. 6. James Abbot McNeill Whistler, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, 1862, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

When this portrait was exhibited at the Kollektiv Ausstellung Gustav Klimt at the 1903-04 Secession exhibition, the critic Ludwig Hevesi commented on a group of the artist’s most recent works as ‘three or four female portraits in all the magical charm of radiant filminess’ of Klimt’s distinctive brushwork, and admired the present work specifically for the ‘gauziest lyricism of which the painter’s palette is capable’ (L. Hevesi quoted in T. G. Natter, op. cit., p. 583). A week or so later Havesi further stated that the Bildnis Gertrud Loew possessed certain stylistic distinctions particular to Klimt’s latest paintings: ‘Take […], at the other end of the scale, the very young lady in white from this year, a pure whisper, with four stripes of pale lilac silk running the length of her gauzy, crumpled dress. Within the shimmering cascade of the fabric, each stripe meanders this way and that, in a random fashion that conceals the most exquisite painterly plan’ (L. Hevesi in ibid., p. 583).

The fashion-conscious artist - whose ‘soul-mate’ was the designer Emilie Flöge (fig. 7) - often incorporated extravagant patterns and geometric designs into his work. However, those who sat for his portraits and may have been actually dressed in the current fashions were often reimagined entirely to the artist’s own taste and for allegorical reasons, as Angela Völker explains: ‘Gustav Klimt clearly had a preference for pale-coloured dresses. A number of the women he painted are wearing white or pastel shades. This does not necessarily comply with current fashion trends. The softly fluid fabrics, often transparent, of the classical style robes in his early allegories are echoed in the thoroughly different pink and white dresses in his portraits of Sonja Knips, Serena Lederer [fig. 1] and Gertrud Loews [sic]. Knips’ highly fashionable frilled dress underlines the wearer’s girlishness, while Serena Lederer’s empire-style Reformkleid designed for a body unrestricted by whalebone-corsets, emphasises the clearly sensual aspect of the wearer. Gertha Felsöványi wears a close-fitting white dress with broad sleeve flounces and a transparent shawl with a pale blue border. Together with the unusual vertical format of the portrait, the dress underlines the petite stature and fragile complexion of this red-haired woman’ (A. Völker in Klimt und die Frauen(exhibition catalogue), op. cit., p. 45).

fig. 7. Gustav Klimt, Bildnis Emilie Flöge, 1902-04, oil on canvas, Wien Museum, Vienna

Klimt’s portraiture was almost exclusively the product of commissions from private individuals, and helped to establish him in Vienna as the most successful artist of his day. Klimt’s art was the subject of heavy promotion through the various national and international exhibitions in which he took part, and through his correspondence with Whistler he became a member of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Engravers. The present work was exhibited on numerous occasions during the artist’s lifetime, both in Austria and Germany. Klimt’s foundation of the Secession and its association with private supporters allowed him to cultivate prospective commissions as well as exhibitions on a large scale, in a manner rarely afforded to artists before him. The growth of private patronage from the haute-bourgeoisie was needed to replace the large-scale commissions from the State and city of Vienna which previously supported many of Austria’s artists. Gemma Blackshaw explains: ‘Vienna’s art market shifted dramatically during Klimt’s career, from the public commissions of the city’s liberal heyday to the rise of private patronage, and from the academy system to the commercial gallery and dealer system. The privatisation of the art-market was a Europe-wide phenomenon, but the small size of Vienna in comparison with other capitals such as London, Paris and Berlin heightened the artists' experiences of these shifts’ (G. Blackshaw in Facing the Modern. The Portrait in Vienna 1900 (exhibition catalogue), The National Gallery, London, 2013, p. 114).

Klimt’s portraits were much in demand and he rapidly became the highest paid artist in Vienna. His popularity and status led to a number of prominent exhibitions – not least the Kollektiv Ausstellung Gustav Klimt at the 1903-04 Secession – but also to a market for reproductions of his best works. In 1908 the art dealer H. O. Miethke, of the eponymous gallery, initiated the creation of a series of 50 lithographs of Klimt’s finest work, simply entitled Das Werk Gustav Klimts. The present work was chosen alongside several of the great Golden period works, as well as a selection of landscapes, portraits and allegorical works. Published from 1908 to 1914 in an edition of only 300 - this was the only series of lithographs produced during the artist’s lifetime. Using collotype lithography and embossed by a signet designed specially by Klimt himself, this collection of prints helped the artist to gain an international reputation outside of the Teutonic European countries, and the Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria was the first person to purchase a folio set of Das Werk Gustav Klimts in 1908.

The sitter in the present work was born Gertrud Franziska Sophie on 16th November 1883, and was the daughter of Sophie Unger and Dr Anton Loew. Her grandfather Heinrich Loew founded the Loew Sanatorium (fig. 5) in the Leopoldstadt area in Vienna in 1859 (it was moved to the Mariannengasse in 1882, and was known as the Wiener Sanatorium Dr Anton Loew from 1907 onwards). During her father’s tenure as director and chief doctor it became one of the most highly-regarded medical institutions in Europe. The portrait was commission by Anton Loew the year before Gertrud's short-lived marriage to Dr Johann Arthur Eisler von Terramare (called Hans). Gertrud (known as Gertha) married the Hungarian industrialist Elemér Baruch von Felsőványi in April 1912 and bore him three children. In November 1923 her husband caught a chill returning from a nightclub and died a few days later.

fig. 5. Photograph of the Loew Sanatorium at Mariannengasse 20, Vienna

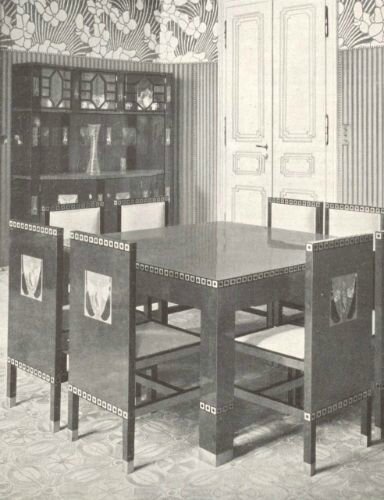

The Loew Sanatorium was particularly notable for its treatment of a number of important fin-de-siècle figures, including Gustav Mahler and Gustav Klimt, as well as Ludwig Wittgenstein. In their study of Wittgenstein’s time in Vienna, Allan Janik and Hans Veigl give an account of the philosopher’s time at the Sanatorium and its milieu: ‘The Loew Sanatorium was a place where the well-to-do frequently went to spend their waning days. Private hospitals were part of the elegant lifestyle of the patrician class at the time. They too were a part of a life of fashionable luxury’ (A. Janik & H. Veigl, Wittgenstein in Vienna: A Biographical Excursion through the City and its History, Vienna & New York, 1998, p. 153). This thriving hospital enabled the Loew family to join society’s elite and give commissions to some of the most important artists of the day. Aside from his daughter’s portrait, Anton Loew also acquired Ferdinand Hodler’s Der Auserwählte (Kunstmuseum, Bern; fig. 8) and Klimt’s Judith I (Belvedere, Vienna; fig. 9). Gertha and her first husband Hans Eisler von Terramare – both serious enthusiasts of the Jugendstil aesthetic - engaged the artist Koloman Moser to design their apartment in the Wiener Werkstätte style (fig. 10). Gertha took over her family’s sanatorium after her father’s death in 1907, continuing to run it until the Anschluss in 1938.

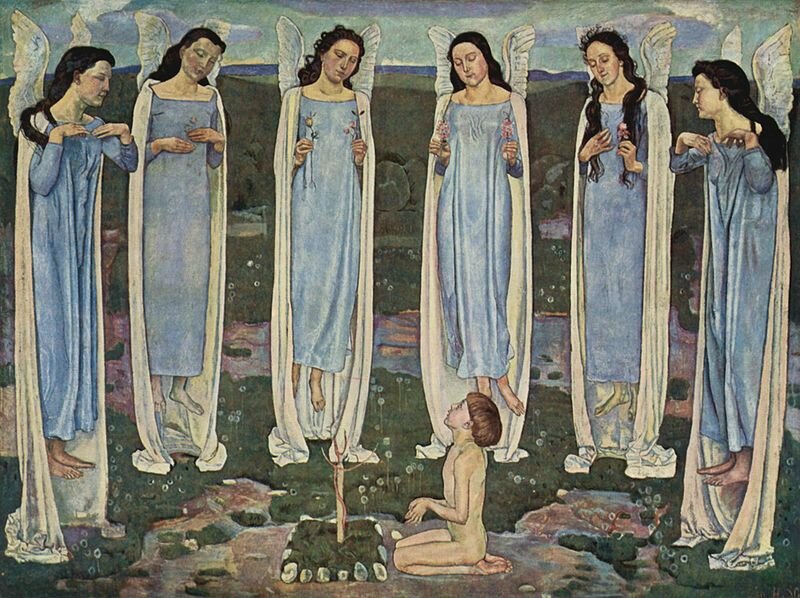

fig. 8. Ferdinand Hodler, Der Auserwählte, 1893-94, oil on canvas, Kunstmuseum, Bern.

fig. 9. Gustav Klimt, Judith I, 1901, oil on canvas, Öterreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna

fig. 10. Photograph of Hans and Gertha Eisler von Terramare's dining room decorated and designed by Koloman Moser

Sotheby's is grateful to Sonja Niederacher and Ruth Pleyer for their research concerning this lot.

This work has been requested for the forthcoming exhibition Gustav Klimt and the Women of Vienna's Golden Age, 1900-1918, to be held at the Neue Galerie in New York from September 2016 to January 2017.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F04%2F34%2F119589%2F126029126_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F78%2F18%2F119589%2F122525383_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F05%2F02%2F119589%2F121570920_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F53%2F17%2F119589%2F120956167_o.jpg)