National Museum of Women in the Arts showcases women artists' uninhibited views of flora and fauna

Maria Sybilla Merian, Plate 70 (from “Dissertation in Insect Generations and Metamorphosis in Surinam”, 2nd Ed.), 1719; Hand-colored engraving on paper; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay © 2014 National Museum of Women in the Arts.

WASHINGTON, DC.- The National Museum of Women in the Arts presents Super Natural, an exhibition focusing on historical and contemporary women artists’ unrestrained absorption with nature. Rather than merely document beauty, artists in this exhibition engage with the natural world as a place for exploration and invention. The exhibition’s paintings, sculptures, photographs and videos present singular plant specimens, little-seen creatures, invented beasties and the artists’ own bodies tucked into the natural landscape. On view June 5–Sept. 13, 2015, Super Natural underscores the way in which historical women artists’ renderings of nature directly inspire today’s artists.

Composed of art from the museum’s collection as well as loans from notable private lenders, Super Natural includes 50 works and installations by 25 artists, including Louise Bourgeois, Ana Mendieta, Maria Sibylla Merian, Patricia Piccinini, Rachel Ruysch, Kiki Smith and Sam Taylor-Johnson. This exhibition will provide context to NMWA’s biennial exhibition Organic Matters—Women to Watch 2015, on view at the same time, which explores the complex relationships between women, art and nature.

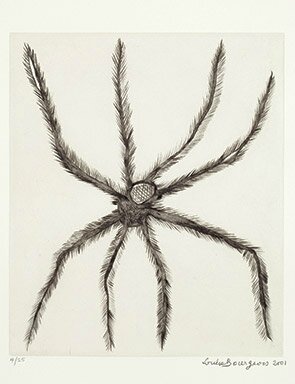

Louise Bourgeois, Hairy Spider, 2001; Drypoint on paper, 19 x 16 in.; On loan from the Holladay Collection; Art © The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA New York; Photo by Lee Stalsworth.

“Throughout history, artists have been inspired by nature. This summer visitors will be able to enjoy two exhibitions exploring women’s complex reactions to the natural world within their art,” said NMWA Director Susan Fisher Sterling. “Both exhibitions demonstrate that women artists, historical and contemporary, are often adventurous, inventive and subversive when dealing with nature in their work.”

From antiquity, women were linked with nature due in part to their generative, life-giving capacities. In art, the female form often stood as the allegorical representation of Spring, Earth or times of the day. Historical women artists took up the subject of nature, but not always in the genteel manner or on the small scale typically expected of them. They created lavishly detailed still-life paintings, botanical studies and images of insects and reptiles. In Super Natural, these historical pieces are juxtaposed with contemporary artworks depicting fruits and flowers at monumental scale or consumed by decay, as well as animals, real and imagined, evoking wonder and fear.

Flora

“Because of their purported keen powers of observation and appreciation for what was pretty or attractive, women artists were historically encouraged to study plants,” said Chief Curator Kathryn Wat. “Like artists of any gender, however, women have always been attracted to nature’s diversity, peculiarities and uncontrollable power.”

In the 17th century, artists served patrons who collected plant and animal specimens as well as paintings and prints of them. In Roses, Convolvulus, Poppies, and Other Flowers on a Stone Ledge (ca. late 1680s), Dutch artist Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750) formed her still life with precise floral details and insect species following the Baroque-era custom of inventing a complex composition based on direct study of individual specimens. American photographer Sharon Core (b. 1965) also creates her works through a meticulous process—Single Rose (1997) appears to be a dreamy, commercial-style floral study while close inspection reveals not an earth-grown flower but a small sculpture crafted from pigs’ ears.

Rachel Ruysch, Roses, Convolvulus, Poppies and Other Flowers in an Urn on a Stone Ledge, ca. 1680s; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay © 2014 National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Sharon Core, Single Rose, 1997; Color print, 14 x 13 in.; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection, Washington, D.C.; © Sharon Core, Image courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery.

In contrast to traditional austere botanical illustrations, Monika E. de Vries Gohlke (b. 1956) enlivens black-andwhite etchings with hand-colored fruits and slightly haphazard cropping. Her works create an impression of expansive and dynamic vegetation, as do the colossal and surreal watercolors of Patricia Tobacco Forrester (1940–2011).

Maggie Foskett (1919–2014) used a photograph enlarger in Rain Forest (1996) to create large-scale, collaged images of nature suffused with light. She credits her childhood in Brazil with her interest in the unfamiliar and sometimes menacing details of the natural world: “It was second nature to be wary, to shake out our shoes in the morning and to look closely at what lay underfoot.”

When rendering fruits, artists often choose to present pristine specimens at peak ripeness. In her time-lapsed, looped video Still Life (2001), Sam Taylor-Johnson (b. 1967) demonstrates the powerful forces of decay as an artfully arranged pyramid of fruit decomposes at an accelerated pace. Through the time-based medium of video, the fruits continually decay and revivify, surpassing the allusions of conventional still-life painting.

Fauna

Unlike plants, which were more easily transported, the study of live animals often required extensive travel to observe them in their natural habitats. Swiss artist-naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717) specialized in the study of insects, which she raised herself, and in 1693, she embarked without a male companion on a dangerous six-month voyage to Suriname, South America, where she worked for two years.

The lavishly detailed images in Merian’s Dissertation in Insect Generation and Metamorphoses in Surinam (2nd edition, 1719) present life cycles of the country’s insects, as well as its native reptiles and mammals. She drew insects devouring seeds and plants while being hunted by predators. In homage to Merian’s print depicting a caiman—a semiaquatic reptile—Monika Gohlke created an etching that shows a caiman attacking a snake that has eaten one of its eggs.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Plate 1 from Dissertation in Insect Generations and Metamorphosis in Surinam, 1719; Hand-colored engraving on paper; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay © 2014 National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Natural history and the study of animals are ostensibly pursued in the interest of intellectual stimulation and enlightenment, but human emotion plays a large role too. Humankind’s anxiety about the strength and capabilities of other animals often drive our inquiries, and we regard other species—particularly those that appear to be most different from us—with both wonder and fear.

To make her sculpture Britain’s Birds and Their Nests (2015), British artist Kerry Miller dissected a discarded natural history book. She painstakingly carved out pages and cut from them images of birds, which she handcolored and reassembled within the book’s cover. Her dense, chaotic arrangement of birds evokes the flapping and cacophony of screeching flocks. Another artist’s book, Peggy Johnston’s Reptalien (2011), is a tongue-incheek interpretation of the natural history book. Its sharp, scale-like folds, punctuated by taxidermy fish eyes, can be curved and flexed, approximating an animal’s essence in a literal manner difficult to achieve through words in a book.

Kerry Miller, Pflanzenleben des Schwarzwaldes (Plant Life of the Black Forest), 2015; Mixed media, hand-cut assemblage; On loan from the artist.

In addition to emotion, humans’ perceptions of other animals are shaped profoundly by social politics. The Stags (2008) by Australian artist Patricia Piccinini (b. 1965) presents two customized motor scooters as living animals. Her art frequently centers on bioengineering and questions what the outcome will be as humanity and technology become more enmeshed. She observes, “Technology has become increasingly natural to us, and it’s this contemporary condition that has allowed me to imagine a lifecycle for machines which is closer to animals than it is to something more artificial.”

Patricia Piccinini, The Stags, 2008; Fiberglass, automotive paint, leather, steel, plastic, rubber; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection, Washington, D.C.; Photograph by Graham Baring

Mother Earth Anew

Adventurous travel and exploration has long been a gendered activity thought to exemplify masculine traits. Yet artist Janaina Tschäpe (b. 1973), who develops performance-based videos and photographs as she travels the world, cites Merian and 19th-century women adventurers as vital sources of inspiration. A gallery in Super Natural is devoted to works by Tschäpe and Ana Mendieta (1948–1985) who both recast ancient ideas about feminine symbols of the earth.

In the early 2000s, Tschäpe photographed models dressed in biomorphic costumes wandering river banks and emerging from ocean waters. Livia 2 (2003) amplifies the mythology of lemanjá, the ancient sea goddess in AfroBrazilian culture. Mendieta’s sculptural interventions in the landscape, called siluetas, represent her own body or its silhouette, but their shapes also resemble archaic goddess sculptures. She built a range of these temporary works from materials such as blood, dirt, rocks, leaves, mushrooms and fire. Photographs titled Volcano Series, No. 2 (1979) document a silueta made with gunpowder and sugar, which Mendieta ignited and let burn. Her works demonstrate that both nature and artists possess formidable productive—and destructive—powers.

This exhibition is co-curated by NMWA’s Chief Curator Kathryn Wat, Curator of Book Arts Krystyna Wasserman and Director of Education and Digital Engagement Deborah Gaston.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F39%2F48%2F119589%2F127886773_o.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F37%2F29%2F119589%2F122491438_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F94%2F14%2F119589%2F102515292_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F71%2F11%2F119589%2F95659131_o.jpg)