Chagall to Malevich: 130 masterpieces of the Russian avant-garde on view at the Albertina

Natalia Goncharova, The Blue Cow, 1911, Vienna, Albertina - Batliner Collection

VIENNA.- The art of the Russian avant-garde numbers among the most diverse and radical chapters of modernism. At no other point in the history of art did artistic schools and artists’ associations emerge at such a breathtaking pace than between 1910 and 1920. Every group was its own programme, every programme its own call to battle – against the past as well as against competing iterations of the present.

Marc Chagall, The walk, 1917-1918, St. Petersburg, Russian State | Chagall® | © Pretty, Vienna | 2016

The Albertina is devoting a major presentation to the diverse range of art from that era: 130 masterpieces by Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky, and Marc Chagall illustrate fundamentally different styles and their dynamic development from primitivism to cubo-futurism and on to suprematism, as well the chronological parallels between figurative expressionism and pure abstraction. In eleven chapters, Chagall to Malevich traces the brief epoch of the Russian avant-garde as a climactic drama stemming from the diversity of avant-garde movements that were diametrically opposed to one another. Enabling the public to see and experience the visual tensions inherent in this heroic phase of Russian art is the stated goal of this exhibition.

Kus'ma Petrov-Vodkin, fantasy, 1925, St. Petersburg, Russian State.

The Russian avant-garde went hand in hand with a phenomenon of comprehensive artistic renewal. Artists drew on differing and occasionally contradictory thematic material and impulses: on the one hand, the Western European avant-garde served as a point of orientation that brought forth such revolutionary expressive forms as fauvism and cubism, after the example of Paris-based artists such as Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso, and Braque. But on the other hand, the Russian artists were equally keen on making reference to the folkloric pictorial tradition of their homeland.

Mikhail Larionov, Officer hairdresser, 1907-1909. Albertina, Vienna - Batliner Collection.

With their demands for pure painting and abstraction as advanced by suprematism (Kazimir Malevich, Ivan Kliun, Olga Rozanova) and constructivism (El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko) alongside the seemingly more traditional forms preferred by figural artists (Marc Chagall, Boris Grigoriev, Pavel Filonov), what they all had in common was an intent to break with the past – representatives of the one side via that past’s radical negation, those of the other by making reference to it. This era’s artists were also united by the desire to arrive at a synthesis between Western Europe’s modernism and the folkloric idioms of Eastern Europe. This desire gave rise to a number of independent, dynamically developing artistic movements – neoprimitivism, rayonism, cubo-futurism, suprematism and constructivism – that were ultimately smothered by the Stalinist regime or forced into an ideologically charged socialist realism.

Natalia Goncharova, The Cyclist, 1913. Saint Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

The artists felt confirmed in their understanding as avant-gardists when Lenin overthrew the bourgeois government in October 1917 and declared the Communist Party the “avant-garde of the working class.” The Bolsheviks’ political program was not only received with enthusiasm by the underprivileged and discontented, but also by the artists, who saw themselves as innovators, as “Futurists”: Larionov and Goncharova, Malevich, Popova, and Exter, Chagall and Kandinsky, Lissitzky and Rodchenko.

Marc Chagall, The violinist, 1912. Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum | Chagall® | © Pretty, Vienna | 2016

The downfall of the Russian avant-gardes had in fact been ushered in with Stalin’s seizure of power in 1924. It had been preceded by Chagall’s emigration to Paris and Kandinsky’s call to the Weimar Bauhaus in the early 1920s.

By 1932 the partnership between the Revolution of the new Soviet state and the artistic avantgarde had finally come to an end: groups and organizations not in line with Socialist Realism were decreed to disband. Malevich’s Suprematism was condemned as formalist degeneration; exhibitions were closed; artists were arrested and persecuted. The utopia of a new society that had been euphorically welcomed and the much-desired implementation of the avant-garde’s artistic spirit in everyday life collapsed.

Marc Chagall, Jew in Red, 1915. St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum | Chagall® | © Pretty, Vienna | 2016

Chagall to Malevich illustrates the striking diversity of disparate but contemporaneous stylistic trends, formal languages, and theories, making use of the “simultaneity of the nonsimultaneous” conceived by German philosopher Ernst Bloch. Radical breaks can be ascertained both within that generation and its nascent artistic groups as well as within the oeuvres of individual artists. The visual juxtaposition of contrasting principles and the highlighting of stylistic leaps between successive or competing “-isms” is an important aspect of this exhibition.

Marc Chagall, Self Portrait with seven fingers, 1912-1913. Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum | Chagall® | © Image Rights, Vienna, 2016

Also a theme are the exciting and controversial teaching activities of two central figures of the Russian avant-garde – Chagall and Malevich – at the art school in Vitebsk. The fronts of the various avant-gardes lay far apart or were locked in battle, with some of the most important artists’ eventual emigration to the West, such as of Wassily Kandinsky and Marc Chagall, owed above all to having been displaced by other, hostile avant-gardes: Kandinsky had to give way to the constructivism of Rodchenko, and Chagall had to make way for Lissitzky and Malevich – both of whom he had appointed to teach at the art school he’d led only a brief while before. Malevich’s radical abstraction leaves no space for Chagall’s poetic variant of the avant-garde. And even so, none of these artists equalled Chagall in his uniting of the complex diversity of an artist’s existence within his own self: an existence between Western European modernism and the Russian shtetl, between the Christian world, naïve folk art, and Judaism.

Liubov Popova, Man + air + Space, 1913, St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

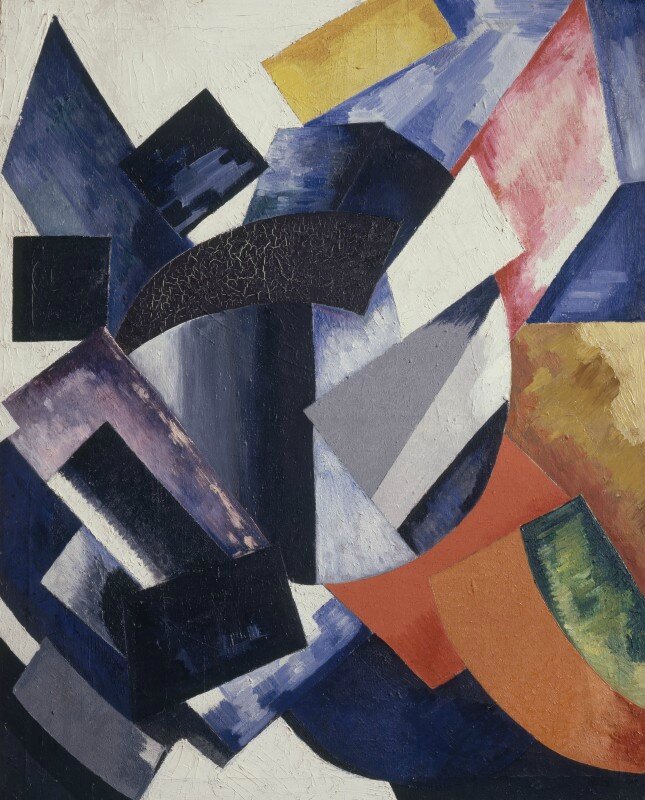

Alexandra Exter, Abstract Composition, 1917-1918, St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

Kazimir Malevich, Aviator, 1914, St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

Kazimir Malevich, Perfected Portrait of Ivan Kliun, 1913, St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

Vasily Kandinsky, On White I, 1920, St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

Kazimir Malevich, Man in Suprematist landscape, 1930-31, Albertina, Vienna - Batliner Collection.

Kazimir Malevich, Red cavalry, about 1932, St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

Kazimir Malevich, Girl in the frame, 1928-1929, St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

Natan Altman, Portrait of the Poet Anna Akhmatova, 1914. Saint Petersburg, State Russian Museum © Bildrecht, Vienna, 2016.

Vladimir Lebedev, Nude model in 1935, St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

Insight into the exhibition hall © Albertina, Vienna

Insight into the exhibition hall © Albertina, Vienna

Insight into the exhibition hall © Albertina, Vienna

Views THE BLACK SQUARE by Kazimir Malevich © Albertina, Vienna

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F42%2F82%2F119589%2F112755609_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F07%2F18%2F119589%2F110945949_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F27%2F29%2F119589%2F103989986_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F05%2F119589%2F95799104_o.jpg)