Exhibition at The Met illustrates what visitors encountered at The palace of Versailles

NEW YORK, NY.- The palace of Versailles has attracted travelers since it was transformed under the direction of the Sun King, Louis XIV (1638–1715), from a simple hunting lodge into one of the most magnificent public courts of Europe. French and foreign travelers, royalty, dignitaries and ambassadors, artists, musicians, writers and philosophers, scientists, Grand Tourists and day-trippers alike, all flocked to the majestic royal palace surrounded by its extensive formal gardens. Opening April 16 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Visitors to Versailles (1682–1789) tracks these many travelers from 1682, when Louis XIV moved his court to Versailles, up to 1789, when Louis XVI (1754–1793) and the royal family were forced to leave the palace and return to Paris.

The exhibition brings together nearly 190 works from The Met, the Palace of Versailles, and more than 50 lenders worldwide. Through paintings, portraits, furniture, tapestries, carpets, costumes, porcelain, sculpture, weapons, guidebooks, and more, the exhibition illustrates what visitors encountered at court, what kind of welcome and access to the palace they received, and what impressions, gifts, and souvenirs they took home with them.

Versailles was always truly international and surprisingly public. Countless visitors from around the world were welcomed at the palace. The openness reflected both a long French tradition of granting the king’s subjects access to their sovereign and a politically calculated display of the French State’s power and wealth. Many visitors described their experiences and observations in correspondence and journals. Court diaries, gazettes, and literary journals offer detailed reports on specific events and entertainments as well as on ambassadorial receptions that were also documented in paintings and engravings.

Informed by these surviving records, the exhibition unfolds in 12 thematically organized galleries to convey the unforgettable experience of visiting Versailles in the 17th and 18th centuries.

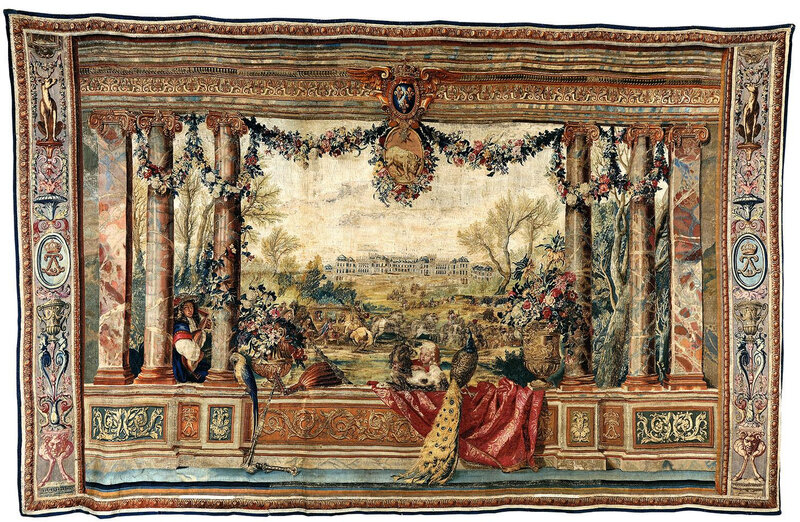

Manufacture Nationale des Gobelins (French, established 1662), The Palace of Versailles and the Month of April, from the series The Royal Residences and the Months of the Year, Jans Fils and workshop, After designs by Charles Le Brun (French, Paris 1619–1690 Paris), ca. 1673–77. Wool, silk, metal thread, 400 × 650 cm, 182 kg. Mobilier National, Paris (GMTT 108/4). Collection du Mobilier national, photo © Isabelle Bideau

Tabletop with Map of France. Probably Manufacture Nationale des Gobelins (French, established 1662), 1684. Hardstones, marble, alabaster, 110 × 78 × 4 cm. Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon (V 3537), on long-term loan from the Musée du Louvre, Paris (OA 6632) © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY, photo by Jean-Marc Manaï

Armchair, ca. 1700–1710. Carved and gilded walnut, caning; velvet, 144.8 × 70.2 × 71.1 cm. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.1738) © 2000–2018 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Charles Cozette (1713–1797), Folding Screen, ca. 1768–70. Wood, oil on canvas, painted leather, 02 × 390 cm. Collection of Monsieur and Madame Dominique Mégret, Paris. Photo by F. Doury

Exhibition visitors will first encounter a large Gobelins tapestry dating to 1673–77. Woven with shimmering gold and silver threads, it depicts the king riding in his carriage toward the palace. The following galleries capture the modes of transportation to Versailles and the French code of dress. Among the reasons to visit the royal residence were its extensive gardens and the prized opportunity to catch a glimpse of the king. Highlight works include a beautiful robe à la française believed to have been worn by the wife of renowned textile manufacturer Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf for her audience with Marie Antoinette, three animal sculptures that were once part of the fountains in the Labyrinth, and uniforms and weapons of the king’s household.

Dress (grande robe à la française) believed to have been worn by the wife of a successful cotton-printing entrepreneur (Christophe Philippe Oberkampf of Jouy-en-Josas, near Versailles) for a visit with Marie Antoinette, 1775–85, French, Silk brocade (woven 1760s). The Kyoto Costume Institute (AC11075 2004-2AB)

Suit (habit à la française), French, 1780s. Embroidered silk (modern breeches), Nordiska Museet, Stockholm (NM.0154745A–C). Image © Nordic Museum, photo by Mats Landin

Court Suit, French, 1774–93, silk, Rogers Fund, 1932 (32.40a–c) © 2000–2018 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Formal Ball Gown (robe parée). Attributed to Marie-Jeanne "Rose" Bertin (French, 1747–1813), 1780s (with later alterations). Silk satin, with silk embroidery, appliqués of satin; metallic threads, chenille, sequins, applied glass paste, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (925.18.3.A–B). With permission of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM

Pierre Le Gros the Elder (French, 1629–1714) & Benoît Massou (French, Richelieu, Indre-et-Loire 1627–1684 Paris), Monkey Riding a Goat, 1672–74. Painted lead, 100 × 118 × 40 cm, 1000 kg.,Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon (MV 7926) © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY, photo by Jean-Marc Manaï

Fox Setting Fire to the Tree with the Eagle’s Nest. Painted lead, 120 × 84 cm, 1000 kg, Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon (MV 7946.1) © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY, photo by Didier Saulnier

Benoît Massou (French, Richelieu, Indre-et-Loire 1627–1684 Paris), Wolf, 1672–74. Painted lead, 89 × 35 × 61 cm, 150 kg, Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon (MV 7181) © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY, photo by Didier Saulnier.

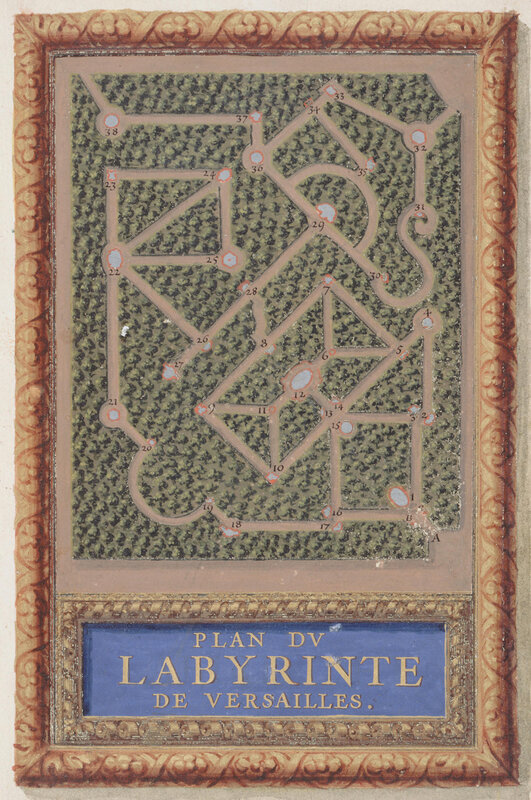

Le Labyrinte de Versailles. Written by Charles Perrault (French, Paris 1628–1703 Paris) andIsaac de Benserade, ca. 1677. Vellum, gouache, ink, gold; binding: red morocco leather, 18.2 × 13.8 × 2.4 cm, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Collection Dutuit (LDUT00724) © Petit Palais/Roger-Viollet

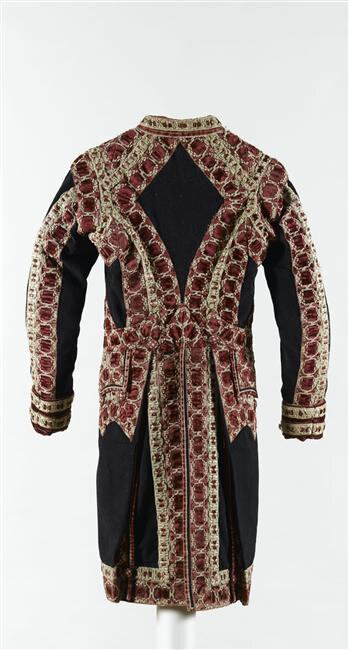

Coat (justaucorps) from the Grand Livery of the Royal Household, 1770–80. Wool with silk and linen trim, 103.5 × 50 × 15 cm, Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon; Gift of the Forum Connaissances de Versailles through the Société des Amis de Versailles, 2011 (V 2011.4) © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY, photo by Gérard Blot

Partisan Carried by the Bodyguard of Louis XIV (1638–1715, reigned from 1643), Paris, ca. 1658–1715. Steel, gold, wood, textile, brass; Rogers Fund, 1904 (04.3.64) © 2000–2018 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Partisan Carried by the Bodyguard of Louis XIV (1638–1715, reigned from 1643), Inscription probably refers to Bonaventure Ravoisie (French, Paris, recorded 1678–1709), Paris, ca. 1678–1709. Steel, gold, wood, textile, brass; Rogers Fund, 1904 (04.3.65) © 2000–2018 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Partisan Carried by the Bodyguard of Louis XIV (1638–1715, reigned from 1643), Jean Berain (French, Saint-Mihiel 1640–1711 Paris), Paris, ca. 1679. Steel, gold, wood, textile; Gift of William H. Riggs, 1913 (14.25.454) © 2000–2018 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The exhibition proceeds to focus on the different types of visitors to Versailles. Overseas ambassadors were received with great fanfare in the sumptuous Hall of Mirrors. Often at the palace to negotiate trade deals, they brought exotic gifts, including a recently discovered silver inlaid cannon given to Louis XIV by the Siamese ambassadors. Incognito visitors were those who assumed lower-level titles to avoid the protocol expected of royal guests. The exhibition features a fashionable French hunting costume presented to one of these incognito visitors, the Crown Prince and future Gustav III of Sweden. Portraits of some travelers, along with souvenirs and guidebooks, are also on view.

Attributed to Pierre Paul Sevin (French, 1650–1710), The Royal Reception of Ambassadors from the King of Siam by His Majesty, 1687. Published by François Jollain (French, Paris 1641–1704 Paris). Etching and engraving on paper, 82 × 52 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Arts Graphiques, Collection Edmond de Rothschild (26985LR) © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY, photo by Angèle Dequier

Cannon, Siamese, before 1686. Cast iron, silver-plated brass inlay, 6.1 × 187 cm, 128.4 kg. The Royal Artillery Museum, Larkhill, United Kingdom (GUN1/020) © Royal Artillery Historical Trust, photo by Dean Belcher

The Arrival of the Papal Nuncio, before 1692. Oil on canvas, 124 × 155 cm. Collection of Aline Josserand-Conan, Paris. Photo by Christophe Fouin

Attributed to Nicolas de Largillierre (French, Paris 1656–1746 Paris), Louis XIV Receiving the Persian Ambassador Muhammad Reza Beg, after 1715. Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon (MV 5461) © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY, photo by Christophe Fouin

Louis Michel Dumesnil (French, Paris 1663–1739 Paris), The Formal Audience of Cornelis Hop at the Court of Louis XV, ca. 1720–29. Oil on canvas, 104.5 × 163 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, On loan from the Koninklijk Oudheidkundig Genootschap (SK-C-512) © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Jacques André Joseph Aved (French, Douai 1702–1766 Paris), Mehmed Said Efendi, Ambassador of the Sublime Porte, 1742. Oil on canvas, 239 × 162 cm, Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon (MV 3716) © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY, photo by Christophe Fouin

Jean Bernard Restout (French, Paris 1732–1797 Paris), The Tunisian ambassador Süleyman Aga, 1777. Oil on canvas, 81 × 68 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Quimper, Bequest of Jean-Marie de Silguy, 1864 (873-1-597) © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY, photo by Mathieu Rabeau

Maupérin, Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh, prince of Cochinchina (modern Vietnam), 1787. Oil on canvas, 175.5 × 116 cm, Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris. Archives des Missions étrangères de Paris, photo © Thomas Garnier

Hunting Costume presented to the Crown Prince and future Gustav III of Sweden. Tailor: Le Duc (French, recorded 1771), recorded 1771. Body: broadcloth with velvet details, gold and silver galloons; lining: wool (coat), silk (waistcoat), chamois (breeches); swordbelt: chamois with gold galloons; boots: leather. The Royal Armoury, Stockholm (11596–99, 27511–12) © The Royal Armoury, Stockholm, photo by Matti Östling

Alexander Roslin (Swedish, Malmö 1718–1793 Paris), Gustav III, 1775. Oil on canvas, 73 × 59 cm. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm (NM 1012) © Åsa Lundén/Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

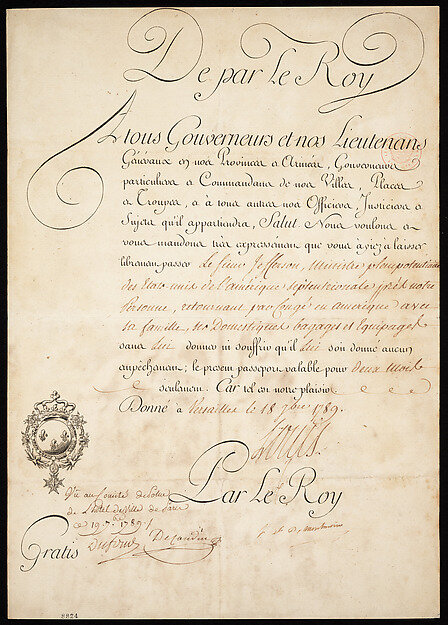

A number of Americans journeyed to Versailles, either as tourists or diplomats. Benjamin Franklin first visited Versailles in 1767 and played a significant role especially after 1776, when France became the colonists’ only military ally in their rebellion against Great Britain. Franklin captivated the French, shamelessly playing to their expectations of Americans, forgoing a wig and dressing in plain, unadorned clothes. The exhibition features one of Franklin’s suits, on loan from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and rarely displayed to the public, as well as his portrait by Joseph Siffred Duplessis and French commemorative porcelain. Also displayed are Thomas Jefferson’s passport signed by King Louis XVI and a gold-hilted sword presented to John Paul Jones.

Joseph Siffred Duplessis (French, Carpentras 1725–1802 Versailles), Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), 1778. Oil on canvas, Oval, 28 1/2 x 23 in. (72.4 x 58.4 cm),The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931 (32.100.132).

Passport Issued to Thomas Jefferson by Louis XVI, King of France (French, Versailles 1754–1793 Paris), September 18, 1789. Brown and black ink on paper, 33.3 × 23.8 cm, The Thomas Jefferson Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (Thomas Jefferson Papers, Box 37, Folder 1, Doc. 8824). Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Presentation Sword to John Paul Jones, a Scottish-born seaman and one of the founders of the American Navy, after he defeated the fifty-gun British frigate Serapis. Hilt by an unidentified goldsmith, mounted by the workshop of Veuve Guilmino, Versailles, 1780. Sword: partly blued steel, gold hilt; scabbard: black-painted leather and gold; case: wood covered with morocco leather with gold tooling and lined with chamois; brass. US Naval Academy Museum. Image courtesy of the U.S. Naval Academy Museum

The exhibition concludes with the dramatic events of October 1789, when an angry mob forced the royal family to return to Paris. Upon visiting the abandoned palace in June 1790, Russian writer Nikolai Karamzin poetically compared Versailles without a court to a body without a soul. Yet his written reflection on the experience—“I have never seen anything more magnificent than the palace of Versailles”—is a testament to visitors’ enduring fascination with the former royal residence, even to this day.

The exhibition design is meant to evoke the grandeur and opulence of Versailles. Five galleries with aligned doorways were constructed to emulate the enfilade of rooms, generating a long theatrical vista and a sense of anticipation for the visitor. Custom-designed wallpaper suggests the defining architectural elements of the palace’s interiors—its marble inlays, pilasters, gilded paneling, wall hangings, and mirrors.

An immersive audio experience brings alive the impressions of visitors to the château and court of Versailles in the 17th and 18th centuries. Using high-quality headphones, listeners can hear dramatizations adapted from actual visitor accounts, produced in atmospheric 3-D soundscapes. The rich, binaural sound evokes the setting, from courtiers walking on a marble staircase to a singer performing a Handel aria in a private salon. Part of the audio production took place at Oldway Mansion, a country house in Devon, England. The unique estate, rebuilt in the style of the palace of Versailles, provided acoustics that ultimately lend the audio experience a compelling authenticity.

"Visitors to Versailles (1682–1789)" at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018. Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

"Visitors to Versailles (1682–1789)" at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018. Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

"Visitors to Versailles (1682–1789)" at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018. Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F50%2F81%2F119589%2F121359672_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F74%2F70%2F119589%2F111709125_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F05%2F46%2F119589%2F110103929_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F33%2F95%2F119589%2F110103720_o.jpg)