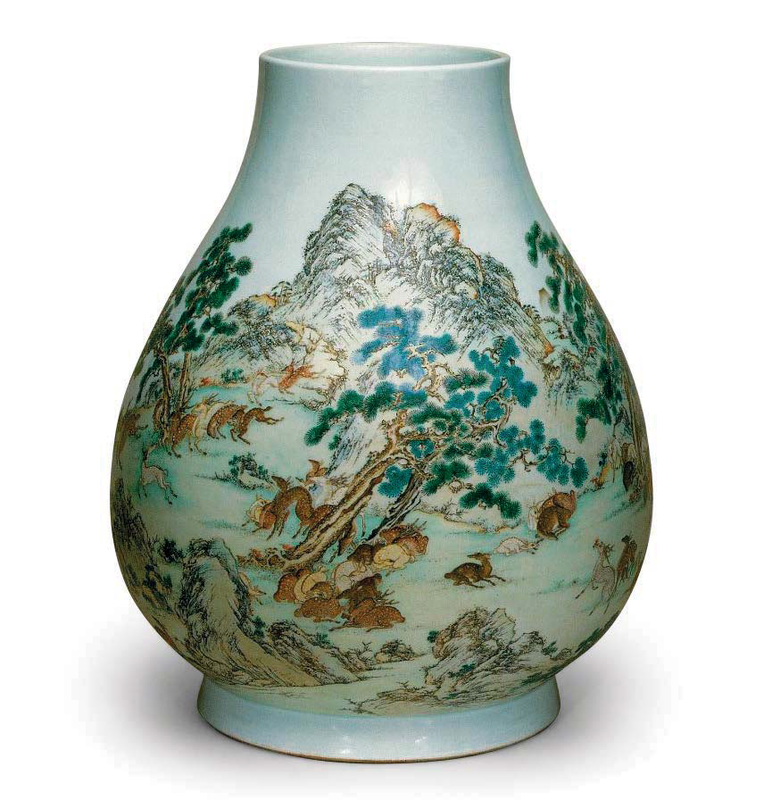

A fine magnificent and exceptionally rare yangcai 'hundred deer' blue-handled vase, hu, Qianlong mark and period (1736-1795)

Lot 2801. A fine magnificent and exceptionally rare yangcai 'hundred deer' blue-handled vase, hu, Qianlong six-character seal mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1736-1795); 17 1/2 in. (44.5 cm.) high. Estimate HKD 20,000,000 - HKD 30,000,000 (US$2,600,000-3,800,000). Price realised HKD 45,100,000 (5,765,230USD). © Christie's Images Ltd 2018.

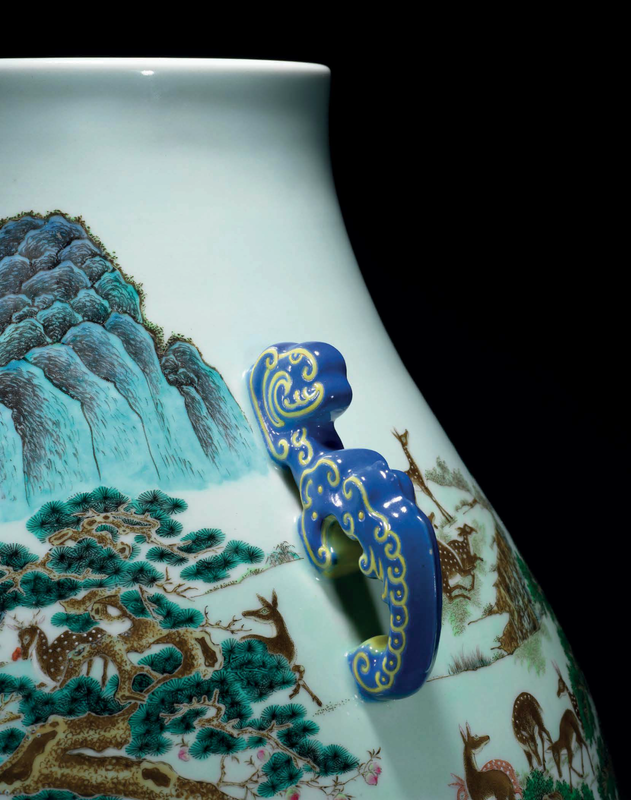

Of archaistic form, the full-bodied vase is superbly painted in vivid enamels with a herd of deer, comprising buck, does and their young with reddish-brown fur, spotted hide and dappled white coats, grazing, gambolling and resting in a lush landscape, amidst pine and peach trees, bamboo, lingzhi, and a meandering stream flowing through blue-shaded rocks from high mountains in the distance, the tapering sides set with a pair of stylised dragon handles decorated in blue and yellow enamels, box.

Provenance: The collection of a Scottish noble family, acquired prior to the 1920s.

This magnificent vase belongs to a very small group of imperial Qianlong ‘hundred deer’ vases, which are of exceptional quality and have blue-enamelled archaistic dragon handles highlighted in yellow enamel. Both the Beijing Palace Museum and the Taipei National Palace Museum have examples of these blue-handle ‘hundred deer’ vases in their collections. The pair of blue-handled deer vases in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, was included in the exhibition Stunning Decorative Porcelains from the Ch’ien-lung Reign《華麗彩瓷 – 乾隆洋彩》, held in Taipei in 2008 and was illustrated in the exhibition catalogue on pages 156-8, exhibit 51 (fig. 1) with further discussion by curator Liao Baoxiu廖寶秀on page 25. An example from the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, is illustrated in Feng Xianming 馮先銘 and Geng Baochang 耿寶昌 (eds.) Selected Porcelain of the Flourishing Qing Dynasty at the Palace Museum 《故宮博物院藏 清盛世瓷選粹》, Hong Kong, 1994, p. 279, no. 12. Another blue-handled deer vase, which was probably originally housed either in the Fengtian Palace (奉天宮, now known as the Shenyang Palace 瀋陽故宮 in Liaoning province) or in the Rehe Palace (熱河行宮, now known as the Chengde Summer Palace 承德避暑山莊in Hebei province), and is today part of the collection of the Nanjing Museum, was included in a joint exhibition with the Art Gallery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Qing Imperial Porcelain of the Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong Reigns, 1995, catalogue, no. 86. A Qianlong deer vase with blue handles from the collection assembled by two members of the Iwasaki family – Baron Iwasaki Yanosuke (岩崎彌之助1851-1908) and Baron Iwasaki Koyata (岩崎小彌太 1879-1945 - and now in the Seikadō Bunko Art Museum, is illustrated in the catalogue Seikadō zō Shinchō tōji. Keitokuchin kanyō no bi 《靜嘉堂藏 清朝陶瓷景德鎮官窯の美》 (Qing porcelain in the Seikado collection - Beauty from the Imperial Kiln at Jingdezhen), Tokyo, 2006, p. 68, no. 58. A further Qianlong deer vase with blue handles was sold by Christie’s Hong Kong in May 2005, lot 2188.

fig. 1 A pair of yangcai ‘hundred deer’ vases with blue-enamelled handles. Qianlong marks and period. Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

There is considerable variety amongst extant Qianlong ‘hundred deer’ vases. The most frequently seen examples have red and gilt handles, such as the example sold at Christie's Paris, 13 December 2017, lot 98 (fig. 2); there is a small group with blue handles, including the current vase, and occasional examples without handles. Both the layout of the design and the quality of the painting are somewhat variable between the groups. It is significant, therefore, that the especially fine examples with blue handles all have the same enamels, painting style and disposition of deer, trees and landscape. Careful comparison of the designs on the Beijing Palace Museum, National Palace Museum, Nanjing and Seikado vases with the current vase show identical depiction – the only difference being the occasional swapping of colours (white for russet, and vice versa) between some of the hinds on the current vase and that in the Seikado collection when compared to the vases in Beijing, Taipei and Nanjing. The positions and painting style of the deer are the same on all the blue-handled vases, only the colours are occasionally exchanged.

A yangcai ‘hundred deer’ vase with iron-red handles. Qianlong mark and period. Sold for EUR 4,151,250 at Christie’s Paris, 13 December 2017, lot 98. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017

Cf. my post: A very rare and magnificent famille rose 'Hundred deer' vase, hu, Qing dynasty, Qianlong mark and period (1736-1795)

The quality of the enamels which have been used to decorate this vase is particularly high. It is worth noting that enamels were on occasion sent to the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen from the specialist imperial ateliers in Beijing, which also supplied the enamels to the porcelain painting workshops in the palace. This is recorded in a palace memorandum as early as the sixth year of the Yongzheng reign (1728), and it is likely that similar provision would have been made for important commissions in the Qianlong reign. The especially rich blue of the handles on this vase, and the small number of others in the group, is unusual. It is a somewhat softer, clearer blue than the basic cobalt enamel seen on the majority of famille rose porcelains. However, the blue of the handles can also be seen as a sgraffito ground on a small number of Qianlong falangcai vases preserved in the palace collections. Vases with this ground are, for example, illustrated in Porcelain with Cloisonne Enamel Decoration and Famille Rose, The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, vol. 39, Hong Kong, 1999, pp. 36-38, nos. 29-31. (no. 30, fig. 3) The blue used on the handles is also strikingly similar in tone to that which provides the solid background colour to two Qianlong falangcai bowls decorated with yellow chi dragons and flowers. One of these bowls was bequeathed by Ernest Grandidier (1833-1912) to the Musée national des artes asiatiques-Guimet in Paris (Illustrated by Xavier Besse in La Chine des porcelaines, Paris, 2004, p. 127, no. 49), while the other, formerly in the collection of Chutaro Nakano, was sold by Christie’s Hong Kong in June 2011, Lot 3650 (fig. 4). It may be significant that the predominant colours on the bowls are blue and yellow, as they are on the handles of the ‘hundred deer’ vases.

fig. 3 A falangcai ‘flowers and butterflies’ vase. Qianlong mark and period. Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing.

fig. 4 A falangcai ‘kui dragons’ bowl. Qianlong mark and period. Sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 1 June 2011, lot 3650. © Christie's Images Ltd 2011

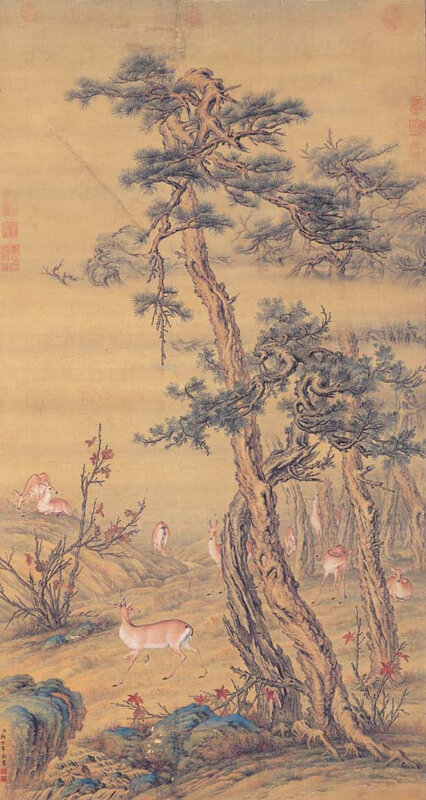

Not only is the quality of the enamels used on these vases exceptional, the quality of the painting is clearly achieved by exceptionally skilled ceramic decorators; probably from amongst the admired artists who were co-opted to paint on imperial porcelains either at the Jingdezhen kilns or the Beijing ateliers. The ceramic artist working on this vase has created very effective juxtapositions of delicate detail in the grasses, undergrowth and the deer themselves, with the bold treatment of the rocks and trees. The layout of the design is also skilful in the way that the landscape, vegetation, and streams are naturalistic whilst providing perfect clearings in which the deer can be placed to best visual advantage. The natural, playful, way in which the deer interact with each other on the vase, as well as the type of landscape in which they appear, is reminiscent of the imperial handscroll A Hundred Deer 百鹿圖 by the Bohemian Jesuit missionary Ignatius Sichelbarth (艾啟蒙 Ai Qimeng 1708-1780), which is preserved in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei (fig. 5). Indeed, images of deer in landscape, without human figures, such as Ignatius Sichelbarth’s A Hundred Deer, and images of smaller numbers of deer, such as the painting Autumn Cries on the Artemesis Plain 苹野鳴秋 by the most famous of the European missionary artists, Giuseppe Castiglione (Chinese name Lang Shining 郎世寧 1688-1766), sold by Christie’s Hong Kong in April 2000, lot 518, and Castiglione’s Deer in an Autumn Forest秋林群鹿圖, also sold by Christie’s Hong Kong in May 2005, lot 1207 (fig. 6), were much admired by the Qianlong Emperor. It is especially interesting to note similarities between the scene depicted in Deer in an Autumn Forest and that on the current vase and others in the blue-handled group. A number of the stances of the deer appear on both the porcelain and the painted silk. The depiction of ancient pine trees with twisted trunks appear on both, and in the foreground of the hanging scroll are rocks of bluish-green and a small stream reminiscent of those seen on the vases.

fig. 5 A Hundred Deer by Ignatius Sichelbarth (1708-1780). Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

fig. 6 Deer in an Autumn Forest by Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1768). Sold for HKD 20,280,000 at Christie’s Hong Kong, 30 May 2005, lot 1207. © Christie's Images Ltd 2005

While discussing the pair of blue-handled deer vases in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taiepei, in the catalogue for the exhibition Stunning Decorative Porcelains from the Ch’ien-lung Reign《華麗彩瓷 – 乾隆洋彩》, op. cit., the curator Liao Baoxiu 廖寶秀 notes a reference in the Huojii dang 活計檔, which incorporates the original records of all works undertaken by the Construction Office of the Yangxindian (養心殿 Hall of Mental Cultivation in the Forbidden City), which exclusively served the Qing imperial family. Liao notes that ‘hundred blessings’ 百祿 vases (which she refers to as jars - zun罇 - because their form originated in ancient bronze vessels) were made early in the Qianlong reign. Liao draws attention to an entry in the Huoji dang relating to the sixth month of the third year of the Qianlong reign (1738) which mentions a ‘hundred blessings’ vase and the command for another to be fired, but without handles「洋彩百祿雙耳罇一件,照樣燒造不要耳子」(see Stunning Decorative Porcelains from the Ch’ien-lung Reign 華麗彩瓷 – 乾隆洋彩, op. cit., p. 156, no. 51). Liao assumes that the ‘hundred blessings’ vase in the text is a ‘hundred deer’ vase similar to the pair with blue handles in the National Palace Museum, and therefore ascribes a 1738 date to that pair of deer vases. However, it is worth noting that the painting style on the only published deer vase without handles, in the collection of the Seikadō Bunko Art Museum (illustrated in Seikadō zō Shinchō tōji. Keitokuchin kanyō no bi《靜嘉堂藏 清朝陶瓷 景德鎮官窯の美》op. cit., p. 69, no. 59 fig. 7) is very different from all the surviving deer vases with blue handles, or indeed any of the more usual examples of this design with red handles.

fig. 7 A yangcai ‘hundred deer’ vase. Qianlong mark and period. Collection of the Seikadō Bunko Art Museum. Seikadō Bunko Art Museum Image Archives/DNPartcom

It has been suggested that the vases may have been made to celebrate the reinstatement of the imperial autumn hunt by the Qianlong Emperor in 1738. However, the Qing historian Mark Elliot has stated that the Qianlong Emperor actually reinstituted the autumn hunt in 1741 (see Mark C. Elliott, Emperor Qianlong – Son of Heaven, Man of the World, New York, 2009, p. 64). This view tends to be borne out by a scroll painting, dated to 1741, Troating for Deer 哨鹿圖 (fig. 8), by Giuseppe Castiglione, in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, which is believed to depict the Qianlong Emperor’s first hunting trip to Rehe in 1741. It is certainly possible that the vases were commissioned to commemorate the re-establishment of the autumn hunt, be that in 1738 or 1741. The unusual choice of blue and yellow for the handles of these deer vases, which does not appear to be replicated elsewhere, suggests that the small group of blue-handled deer vases were a special order, perhaps to commemorate a particular occasion. In view of the outstanding quality of the painted enamels on the blue-handled vases, the 1741 date may be more likely, since in the ‘Introduction’ to the Stunning Decorative Porcelains from the Ch’ien-lung Reign catalogue, the author notes that many of the particularly fine imperial Qianlong falangcai/yangcai porcelains in the National Palace Museum collection can be dated to the period from the 5th to the 9th year of the Qianlong reign (i.e. 1741-1744).

fig. 8 Troating for Deer by Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1768). Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing.

There are several other indications as to when in the Qianlong reign these remarkable vases were made. Recent research has suggested that spectacular imperial porcelain vessels covered with continuous overglaze enamel landscape scenes in Chinese style – like that seen on the blue-handled deer vases - were only made during the period when the great ceramicist Tang Ying (唐英 1682-1756) was supervisor of the imperial kilns. If this is the case, then it would follow that these vases must have been made in or before 1756. In addition, Professor Peter Lam has conducted detailed research into the form of reign marks during the Qianlong reign, and the reign mark on the current vase and others in the blue-handled group accords with the style which Lam denotes ‘style 6’ (Peter Y.K. Lam, ‘Towards a Dating Framework for Qianlong Imperial Porcelain’, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, vol. 74, 2009-2010, p. 24). Lam suggests that this style of reign mark was prevalent from the late 1740s to the late 1780s, but notes that the dates could be somewhat stretched at either end (i.e. perhaps into the early 1740s). In view of the various clues to dating available at present, it seems probable that fine blue-handled ‘hundred deer’ vases, such as the current example, were made in the period 1738-1756.

The National Palace Museum, Taipei, has in its collection an anonymous Ming dynasty handscroll with a similar theme of ‘a hundred deer’ in landscape with the addition of groups of immortals. It is worth noting that in most instances in the Chinese arts the term ‘a hundred’ was not intended to be taken literally, but simply implied an abundance. The title of the Ming dynasty scroll, A Hundred Blessings百祿圖, explains the rebus provided by the theme. The deer – lu 鹿 – in the paintings (and on the vases) provide a rebus for the word lu祿, which can mean good fortune or blessings. A hundred deer百鹿 bai lu thus suggests the wish受天百祿 shoutian bailu ‘May you receive a hundred blessings from heaven’. The number one hundred is implied by two other rebuses within the design on the current vase. One of these is provided by the inclusion of a cypress tree in the design, since the name for cypress in Chinese is also bai 柏. The other rebus is the inclusion of white deer amongst the brown and russet animals, since the word for white in Chinese is bai 白 – another homophone for the word meaning a hundred. It is also interesting that there are several deer with white coats depicted on the vessels – both stags and hinds -since white deer were regarded as being especially auspicious. The Jin dynasty scholar Ge Hong (葛洪 AD 283-343) wrote in his Baopuzi (抱朴子The Master Who Embraces Simplicity) that the deer can live one thousand years and turns white after five hundred years. A white deer therefore symbolises long life, as well as good fortune and nobility.

More generally, deer had a number of other auspicious associations in traditional Chinese culture. Shoulao, the Star God of Longevity, is usually depicted accompanied by a spotted deer, crane, peach and pine tree. Each of these, including the deer, thus represents long life. Deer were also believed to be the only animals that are able to locate lingzhi, the fungus of immortality. Multicoloured lingzhi fungus are included in the composition on the current vase, as are fruit-laden peach branches, emphasising the wish for longevity. The theme of ‘a hundred deer’, is therefore an especially potent wish for health, happiness, good fortune, and long life, especially when combined with peaches and lingzhi fungus.

The depiction of the deer in a rocky, wooded, landscape with winding streams on these vases was not only intended to showcase the ceramic artists’ skill in painting such encircling panoramas, but was undoubtedly intended to recall imperial gardens and hunting parks, which were frequently stocked with animals - especially deer. As early as the Bronze Age dynasties of Xia and Shang, their rulers are traditionally believed to have constructed gardens and parks. The first Qin dynasty emperor, Qin Shihuangdi (221-207 BC), is thought to have conceived the initial design for the Shanglin Park to the west and south-west of the capital Chang’an (modern Xi’an), and the Upper Grove Park near his palace was used partly as a leisure park and partly as a hunting park. The Han dynasty Emperor Wudi (140-87 BC) expanded this park and had artificial lakes created within it. Some of the pools were specifically dug to provide water for the deer, which were among the animals and plants brought to the imperial park from all over China (see N. Titley and F. Wood, Oriental Gardens, British Library, London, 1991, p. 72). The second Sui dynasty emperor (Emperor Yang隋煬帝AD 598-618) ordered the construction of a similar park outside his capital at Luoyang, into which he too commanded deer to be brought. The Northern Song emperor Huizong (AD 1101-26) was another enthusiastic builder of gardens, and the imperial garden at Kaifeng contained many different types of deer amongst its varied animal inhabitants. The Southern Song emperors also enjoyed gardens at their capital at Hangzhou, and Marco Polo’s Travels mentions a large park on the shores of West Lake containing many types of deer in the Yuan dynasty. Deer became well established in Chinese imperial gardens and parks for their visual attractiveness and interesting variety, but also to provide sport for imperial hunting parties.

Even prior to their conquest of China, organised hunts were an intrinsic part of Manchu culture. In 1630 Hong Taiji (who as successor to Nurhaci became the second emperor of the Qing dynasty 1636-43) established a hunting ground near Shenyang, which had become the administrative centre for the Manchus in 1625. Hong Taiji explained his reasons for encouraging hunting in a speech in 1636: ‘What I fear is that children and grandchildren of later generations will abandon the Old Way, neglect shooting and riding, and enter into the Chinese Way’. He predicted that if this were to happen then the Qing dynasty would fall (see Mark C. Elliott, Emperor Qianlong – Son of Heaven, Man of the World, op. cit., p. 52). However, it was the Kangxi Emperor, who established the Manchu tradition of regular imperial autumn hunts at Mulan. The Kangxi Emperor believed that: ‘The hunt is also training for war, a test of discipline and organisation: the squads of hunters have to be organised on military principles, not according to convenience on the march or family preferences (see Jonathan D. Spence, Emperor of China – Self-portrait of K’ang-hsi, Harmondworth, 1977, pp. 12-13). The Qianlong Emperor was also proud of the Manchu heritage and concerned that it might be lost. He feared that the Manchus would become too integrated into Chinese culture and would lose their martial capabilities. Hunting may have been enjoyable for the emperor and his retinue, but it was also important for the preservation and development of riding and shooting skills as well as for practice in the organisation and deployment of troops.

Not surprisingly, therefore, the theme of deer and deer hunting in art was important to the Qianlong emperor, as can be seen in numerous court paintings dating to his reign as well as in the decorative arts - not only porcelain, but other media, including cloisonné enamel. The subject was not only an auspicious one, but closely tied to important Manchu traditions. Rarely, however, was the theme so well depicted as it is on the magnificent blue-handled ‘hundred deer’ vases like that in the current sale.

Christie's. Multifarious Colours - Three Enamelled Qianlong Masterpieces, Hong Kong, 28 november 2018

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240313%2Fob_2a714e_431771440-1632540147515998-38392421212.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F52%2F41%2F119589%2F129167485_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F70%2F50%2F119589%2F129167314_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F86%2F119589%2F129167008_o.jpg)