Unveiling timeless treasures from the collection and library of Count & Countess de Ribes

PARIS.- The name “de Ribes” resonates internationally with a timeless sense of style – the essence of French chic and elegance. On 11 and 12 December, Sotheby’s Paris will offer for sale a selection of historical pieces from the collection of the Count and Countess de Ribes. Held over two sessions, the auction will present artworks, fine books and manuscripts from the family’s ancestral home in Paris – covering three centuries of French history.

In the exquisite setting of their “Hotel Particulier”, built in 1865, Edouard de Ribes and his wife Jacqueline, née de Beaumont, were custodians of an exquisite collection of objects that had entered the family in the 18th century. They were also keen collectors, acquiring works of the highest-quality to enhance the sumptuous and sophisticated décor of their mansion. The Count and Countess were recognised as respected patrons in the art world, and the intellectual and artistic elite would gather at their home for parties that encapsulated the French “art de vivre”. In line with this, part of the proceeds from the sale will benefit philanthropic causes and cultural organisations.

The first auction will be dedicated to the “treasures” of the collection – exceptional pieces boasting remarkable provenance that have been passed down through the ages by distinguished historical figures. Famed previous owners include Louis XIV and XV at the Château de Versailles, Louis XVI at the Château de Saint-Cloud, the Count of Artois at the Palais du Temple, Marie-Antoinette and the Duke of Orléans. Eminent figures from the decorative and fine arts are represented, including Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Hubert Robert, André-Charles Boulle and Bernard II Vanrisamburgh.

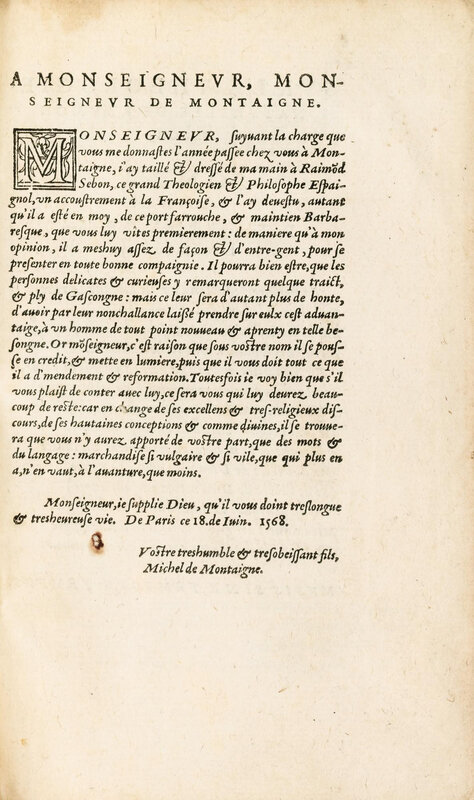

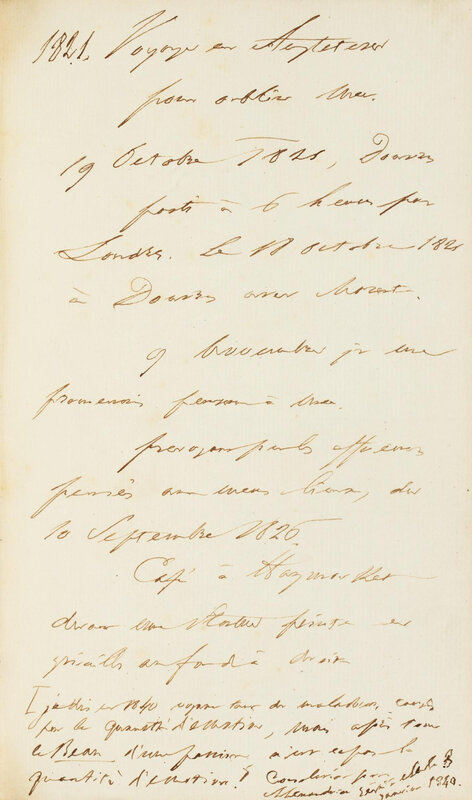

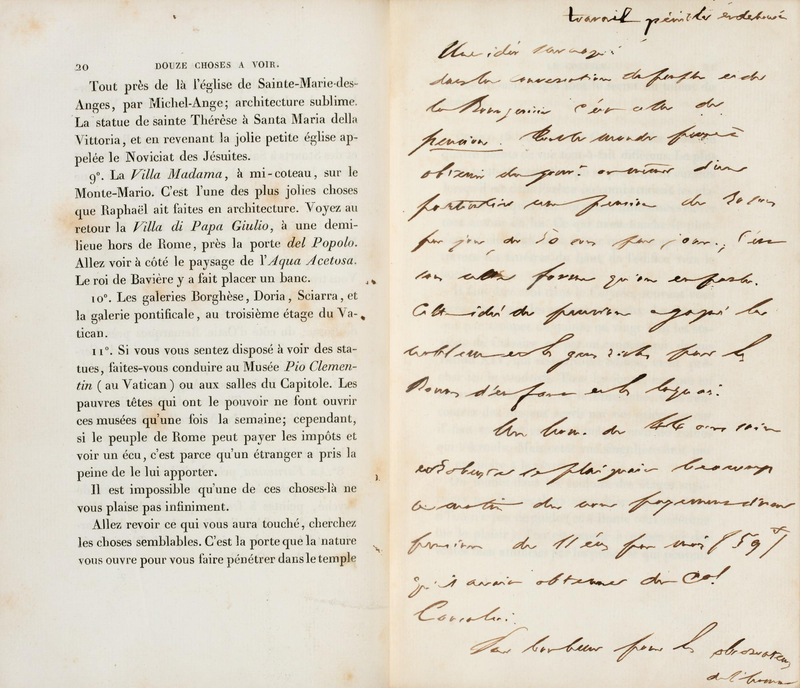

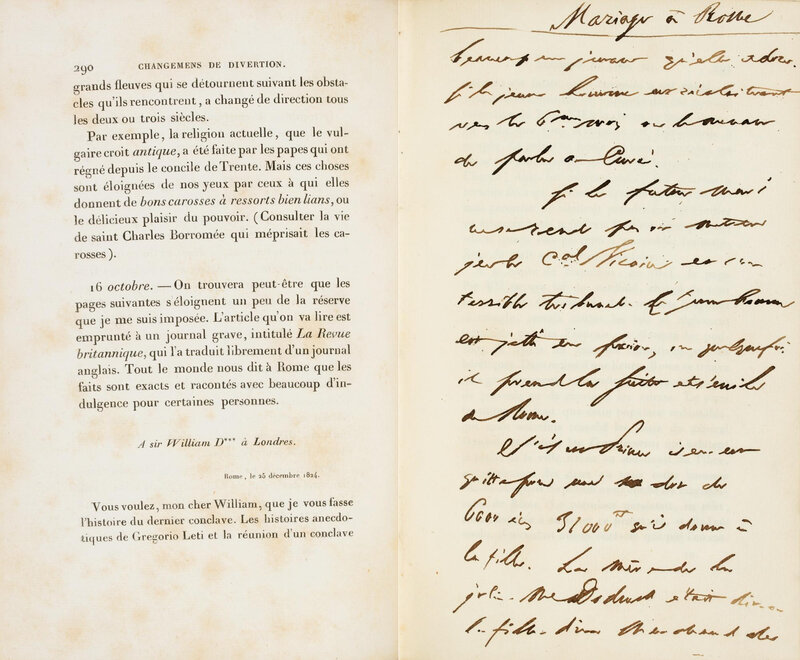

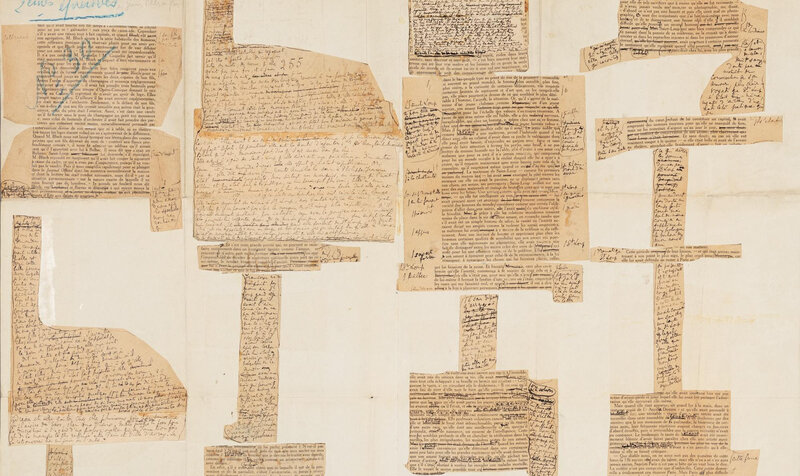

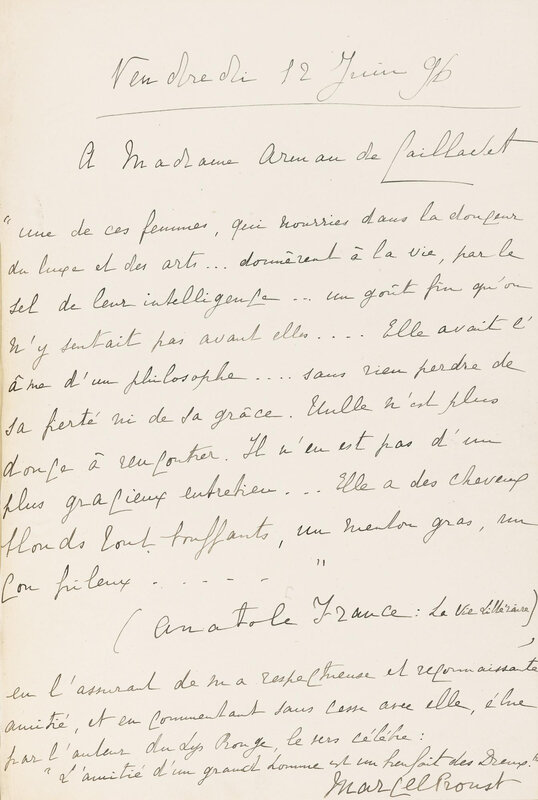

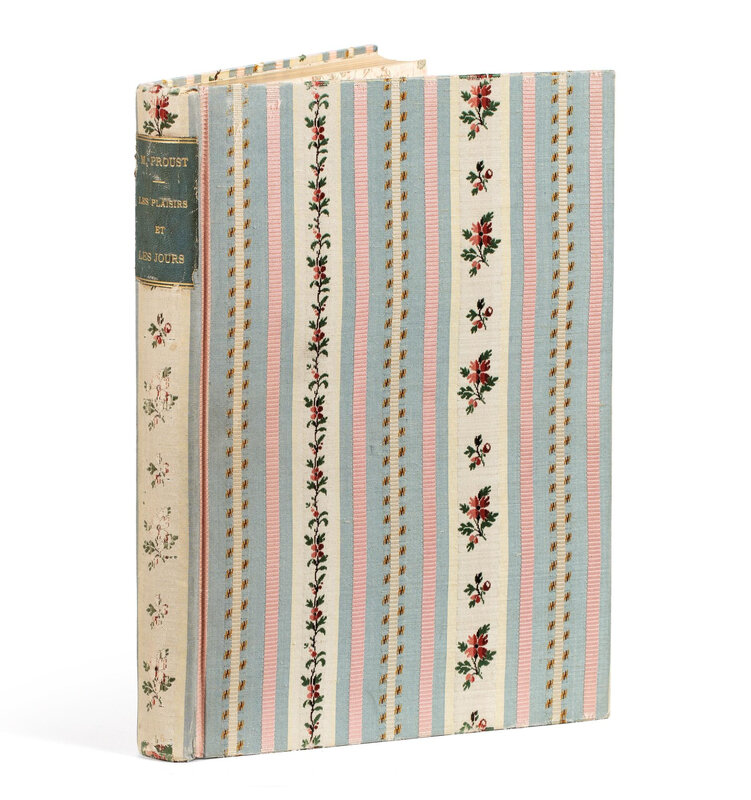

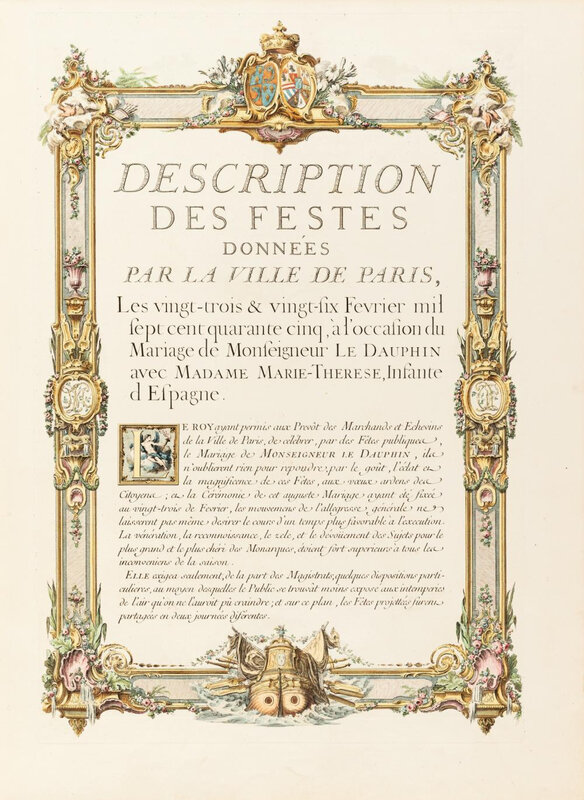

The second sale is a sanctuary for fine books, featuring precious volumes from the 16th to the 21st centuries. Built up by two generations of bibliophiles, Édouard de Ribes (1923-2013) and his father Jean (1893-1982) – both members of the prestigious Société des Bibliophiles François – the exceptionally diverse library has only been seen by a few select visitors until now.

Major paintings and prestigious commissions

Leading the paintings is Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun’s rediscovered Juno borrowing the belt of Venus (estimate: €11.5 million), which had been believed lost since 1803 and until now had only been known from a preparatory study. Commissioned in 1781 by Charles X, the count of Artois and younger brother of reigning king Louis XVI, the painting was passed down to the Count’s godson before entering the line of descent to the Comte and Comtesse de Ribes.

This mythological composition is based on a scene in the Iliad, and depicts Venus – whom the hedonistic aristocracy of the French courts had long worshipped in a cult-like fashion – and was one of the most important paintings the artist sent to her first Salon, shortly after being accepted into the Royal Academy.

Lot 3. Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Le Brun (1755 - 1842), Juno Borrowing the Belt of Venus. Oil on canvas ; signed and dated lower centre: Louise Le Brun. f.1781, 147,3 x 113,5 cm ; 58 by 44 2/3 in. Estimate 1,000,000 — 1,500,000 EUR. Courtesy Sotheby's.

- Seized from the Temple on 7 June 1794 [19 Prairial, Year II] by revolutionary authorities, along with other works belonging to the prince, and sent to the Hôtel de Nesle, Rue de Beaune;

- Transferred on the orders of the Interior Minister to Antoine Gabriel Jourdan (1740-1804), 'farmer' from the Müntzthal national glassworks in Lorraine;

- His sale, Paris, 4 April 1803 [14 Germinal, Year IV], lot 90 (withdrawn after a bid of 1,710 francs);

- By descent to his godson, Aimé Gabriel d'Artigues (1773-1848), director of the Saint-Louis glassworks;

- His daughter, Anne Gabrielle d'Artigues (1833-1889), who in 1853 married Charles-Édouard, Comte de Ribes (1824-1896), mayor of Belle-Église (Oise);

- Their son, Charles-Aimé-Auguste, Comte de Ribes (1858-1917);

- His son, Jean, Comte de Ribes (1893-1982);

- His son, Édouard, Comte de Ribes (1923-2013);

- The current owners.

Exhibited: - Paris, Hôtel de Lubert, November 1781

- Paris, Salon de 1783, n°113.

RELATED WORK

Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun’s preparatory study for the final version is in a New York private collection (oil on canvas; H. 49 cm; L. 38.5 cm ; fig. 1)

E.L. Vigée-Le Brun, Junon demandant à Vénus de lui prêter sa ceinture magique, modello, collection privée

The portraitist Élisabeth Louise Vigée painted very few history paintings during her teenage years, apart from the three Allegories of the Arts that she sent to the Salon of the Académie de Saint-Luc in 1774 (see exh. cat. Vigée Le Brun, Grand Palais, 2015-16, p. 131, no. 31). From a very young age, while accompanying her mother on visits to the most important Paris collectors, and later in the stock of the connoisseur and art dealer Jean Baptiste Pierre Le Brun, whom she married in 1775, she was able to admire the boudoir paintings of the mid-eighteenth century, and it was these that were her inspiration.

In 1779, four years into her marriage, Vigée-Le Brun produced a pastel allegory for Pierre Louis Éveillard de Livois, a collector from Angers: Innocence Taking Refuge in the Arms of Justice (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Angers, inv. no. MBA 25J.1881). This was the first time that she devised a composition depicting two young women, one fair and one dark-haired. From this year on and until she left France at the very beginning of the French Revolution, the portraitist produced a number of compelling history paintings. In 1780, the year that her daughter Jeanne Julie Louise was born, she created a composition with a mythological theme: Venus Tying the Wings of Love, commissioned by her most important private patron, the Comte de Vaudreuil. This pastel is known mostly through the etched and engraved print published in 1786 by the Dresden printmaker Christian Gottfried Schulze. Vigée-Le Brun painted another history painting in the same year, an allegory of Peace Bringing Back Abundance (fig. 2), which she presented as her reception piece for admission to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture on 31 May 1783. In 1781, Vigée-Le Brun produced the present painting, Juno Borrowing the Belt of Venus. This was commissioned by the younger brother of Louis XVI, Charles Philippe de France, Comte d’Artois, (fig. 3) – a prince known before the Revolution for his expensive whims and libertine lifestyle. In forming his collection Artois was guided by his best friend the Comte de Vaudreuil, cousin and lover of the Duchesse de Polignac and a great admirer of works of the modern French school.

E. L. Vigée-Le Brun, La Paix ramenant l’Abondance, Paris, Musée de Louvre © RMN-Grand Palais / Philippe Fuzeau

Jean-Baptiste Moitte, Charles Philippe de France, comte d’Artois en chasseur, Amiens, Musée de Picardie Photo © RMN-Grand Palais / Agence Bulloz

Before painting the full-size version of Juno, Vigée-Le Brun submitted a very finely finished preparatory modello in oil on canvas for her royal patron’s approval (fig. 1; see exh. cat. Vigée Le Brun, Grand Palais, 2015-16, no. 35), in which she depicted the two most important (and to some degree rival) goddesses of Graeco-Roman mythology: Juno and Venus (examples exist of French painters from earlier generations, such as Pierre Mignard and Jean Raoux, producing modelli of this type before the execution of important works of art).

E.L. Vigée-Le Brun, Junon demandant à Vénus de lui prêter sa ceinture magique, modello, collection privée

The theme of this mythological composition with three figures was drawn from an episode in Book XIV of the Iliad. Homer’s poem recounts the story of the siege of Troy in Asia Minor by a coalition of Greek city states. The initial cause of the war was the abduction of Helen – wife of Menelaus, King of Sparta, and sister-in-law of Agamemnon, King of Mycenae – by Paris, son of Priam, King of Troy. Juno, who was Jupiter’s sister as well as his wife and therefore queen of the Olympian gods, had a fierce hatred of Troy because Paris had humiliated her by preferring Venus (Aphrodite in Greek), mother of Cupid, in a beauty contest. She meant to take revenge by ensuring a Greek victory. But Troy and its mortal inhabitants were protected by the all-powerful Jupiter. To rekindle her unfaithful husband’s love, she asked Venus to lend her a multi-coloured belt woven from threads of desire and passion, containing all the charms of seduction: the girdle worn across the breast that the Romans called cestus himas. She felt sure that if she wore this enchanted article, Jupiter would not be able to resist her and would abandon the Trojans.

Venus, who had for a long time been a sort of cult figure for the hedonistic aristocracy at the French court, embodies the pleasures of licit and illicit love. The goddess prevailed at that time in the king’s palaces and in the homes of rich private individuals; many Academicians paid homage to her. The work of François Boucher (1703-1770), who had died not long before, and his successor Jean Baptiste Marie Pierre (1714-1789) represents a clear expression of their contemporaries’ taste for female nudity and it is evident that for them mythology was simply a pretext for revealing the charms of alluring models.

Juno Borrowing the Belt of Venus held a prime position among the large number of works that Vigée-Le Brun entered to her first Salon after being received into the Académie. The critical reception was mostly positive, but particular note should be taken of the review by Barthélémy Mouffle d’Angerville, editor of Mémoires Secrets:

"If this composition [Peace Bringing Back Abundance]…should not be enough to assure Madame le Brun the honour of a place among the artists of history, it would be difficult to resist another whose theme drawn from Homer proves that she can, like her masters, show a passion for the divine works of the prince of poets as well as of painters, since the latter never fail to be inspired by him. The subject is Juno borrowing the belt of Venus. There are three figures, with Cupid playing a part, amusing himself by playing with the belt, which has already been relinquished to the Queen of Olympus: he is reluctant to let it go, as though aware of its worth and fearing that if she loses the belt his mother will also lose her most precious charms. Indeed, perhaps in an extension of this idea, or in homage to the first among goddesses, whom the artist has felt bound to make her principal figure, no admirer in this instance could fail to prefer Juno to Venus. The first, dark-haired, combines both the majesty of the throne and the piquancy of beauty; the second, fair-haired, exhibits none of the nobility of a divinity, even bringing to mind a common woman, a little banal and consequently lacking in seductive qualities. Despite this defect relating to the head, so crucial in history painting, the body is full of feminine charms, its nudity in the style of Boucher, very lovingly depicted and with the same tones and colouring. To judge by the price it fetched, the painting must have much merit, since Monsieur le Comte d'Artois was advised to pay fifteen thousand francs for it. He bought it at that price and his Royal Highness is now its owner."

Among other paintings that belonged to the Comte d’Artois, mention must be made in particular of A Young Woman Praying at the Altar of Love by Jean Baptiste Greuze (Wallace Collection, London, inv. P441); Mars leaving Venus, on a chariot harnessed with sprightly horses driven by Bellona, the spirit of Victory floating on a cloud above, with Venus reclining in her bed in her palace beside the Three Graces by François Guillaume Ménageot (lost work); Rinaldo and Armida by François André Vincent (lost from the French Ministry of the Interior after 1879) and its pendant The Loves of Paris and Helen by Jacques Louis David (Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. 3696; fig 4). This last painting, dated 1788, has very close thematic and chromatic links with Vigée-Le Brun’s Juno Borrowing the Belt of Venus, painted seven years earlier.

J. L David, Les Amours de Pâris et d’Hélène, Paris, Musée du Louvre © RMN-Grand Palais / Gérard Blot

Known for his reactionary ideas, the Comte d’Artois was an unpopular prince, and he was forced to leave France just two days after the Storming of the Bastille. He was accompanied by his family and much of the Polignac set, including his friend Vaudreuil. Since his oldest son, the young Duc d’Angoulême (1775-1844), had since early childhood been Grand Prior of the Maltese Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, Artois used the palatial Hôtel du Temple as his residence in town. Most of his collection of works of art and precious objects was located there, even those that before the Revolution had graced his other residences near Paris, the Château de Bagatelle and Château de Maisons.

When the revolutionaries seized the Temple, Juno Borrowing the Belt of Venus and other paintings were transferred as national assets to the Hôtel de Nesle in Rue de Beaune. Here, artistic treasures seized from those who had emigrated or been guillotined were accumulated. On 19 Prairial, Year II of the revolutionary calendar (7 June 1794) and over the following days, an inventory was compiled: Inventory of the Works of Art previously belonging to the emigré d’Artois, found in the Temple and retained by the Temporary Arts Commission in the presence of citizen Virginien Leduc, Superintendent of the Department (French National Archives, ref.: F17 1269. Dossier 20). It was here too, on 15 Fructidor, Year II of the revolutionary calendar (1 August 1794), that Jean Baptiste Pierre Le Brun, Vigée-Le Brun’s divorced husband, drew up an estimate or appraisal of the works of art that had belonged to the emigré d’Artois (French National Archives, ref.: F17 1267, no. 34: ‘Juno coming to borrow the Belt of Venus. Life-size, half-length figure: on canvas, height 63 pouces, width 41 pouces. By Citizen Le Brun [valued at] 3,000’ (cf. Louis Tuetey, ed., Procès-verbaux de la Commission temporaire des Arts, Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, 1912, vol. I, p. 380).

The painting remained for two years in the Nesle depot, but on 14 June 1796 (26 Prairial, Year IV), the Minister for the Interior, Pierre Bénézech, sent the custodian Jean Naigeon the following message: ‘Citizen Jourdan, farmer of the Mandtzal national glassworks, offers to pay the sum of 120,000 francs for some of the engravings and paintings kept at the Hôtel de Nesle. Please note that he is authorised to choose those that he requires.’ Jourdan was director of the Müntzthal national glassworks in Moselle, formerly the Saint Louis royal crystal factory, based in Saint-Louis-lès-Bitche. Among the paintings he chose were the Juno and Venus by Vigée-Le Brun and Mars leaving Venus by Ménageot.

Citizen Jourdan was Antoine Gabriel Aimé Jourdan (fig. 5), former secretary to his foster father, Jean Gilles du Coëtlosquet, Bishop of Limoges (1700-1784), who was preceptor to the future Louis XVI, Louis XVIII and Charles X, the sons of the Dauphin, Louis Ferdinand, and the Dauphine, Marie Josèphe de Saxe. Jourdan had served as president of the District des Petits-Augustins and the Section des Quatre-Nations, districts of revolutionary Paris. He had been one of the witnesses to the September Massacres (1792) and in 1795 he published a chilling account of the events.

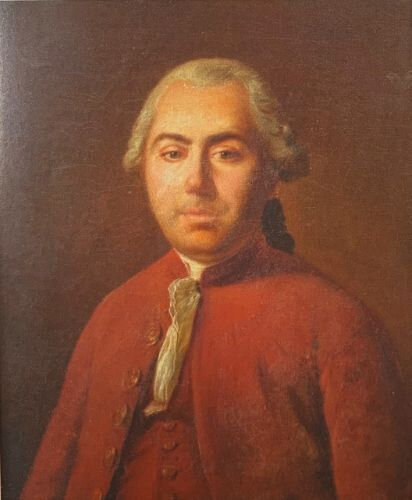

Ecole française du XVIIIe siècle, Portrait d’Antoine Gabriel Aimé Jourdan, localisation inconnue.

Two pendant paintings by Hubert Robert, Le matin and Le soir (estimate: €1-1.5 million), are perfect examples of the capriccio scenes of ancient ruins produced by the artist during the 1770s and 1780s. Both were commissioned directly by Madame Geoffrin, who hosted one of the most brilliant salons in Paris at her house on Rue Saint-Honoré. A rare opportunity to acquire works by the artist still in private hands, these paintings have not been seen since they last appeared at auction in 1961.

Lot 31. Hubert Robert (1733 - 1808), Le matin (Morning) and Le soir (Evening). Oil on canvas, a pair ; both signed, bottom right: peint par H. Robert, 165,2 x 129,5 cm (1); 165 x 129,8 cm (2) ; 65 by 51 in. (1) ; 65 by 51 in. Estimate 1,000,000 — 1,500,000 EUR. Courtesy Sotheby's

Provenance: - Madame Marie-Thérèse Geoffrin (1699-1777) ;

- Marquise de La Ferté-Imbault (1715 - 1791), her daughter ;

- Louis-Dominique d'Estampes, marquis of Mauny (1734 - 1815), his nephew ;

- Collection of comte de La Bédoyère ;

- His sale Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, 8 June 1921, lots 2 and 3 (ill.) ;

- Collection H. de Montbrison ;

- His sale, Galerie Charpentier, 8 June 1933, lots 6 and 7 (ill.) ;

- Anonymous sale, Paris, Palais Galliera, Maître Etienne Ader, 20 June 1961, lots I and J, pl. VI and VII (ill.)

Literature: - P. de Nolhac, Hubert Robert, Paris, 1910, cité et décrit pp. 48-49

- M. Fumaroli, dans cat. exp. Madame Geoffrin, Une femme d'affaire et d'esprits, La Vallée aux Loups, Musée de Chateaubriand, 2011, p. 74

- J.-C. Gaffiot dans cat. exp. Madame Geoffrin, Une femme d'affaire et d'esprits, La Vallée aux Loups, Musée de Chateaubriand, 2011, p. 106, sous le N° 42

- M.-M. Dubreuil dans cat. exp. Hubert Robert, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2016, p. 106

- S. Catala et C. Voiriot dans cat. exp. Hubert Robert, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2016, p. 311, sous le n. 88

- C. Voiriot dans cat. exp. Hubert Robert, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2016, p. 457 (with a mistake regarding the format she considers "oval")

Note: Aprolific and versatile artist of unfaltering talent, Hubert Robert was one of the painters who left their decisive imprint on the art of the last years of the Ancien Régime.

Initially destined for a career as a sculptor, his early training was under Michel-Ange Slodtz, who taught him the rudiments of perspective. However, he soon turned his energies towards painting and in the company of the Comte de Stainville – the future Duc de Choiseul – he travelled to Rome in 1754. He spent eleven decisive years there developing his art. As well as undertaking advanced and careful studies of the antique and modern Roman monuments that would always feature in his work, he became friends with Fragonard and crossed paths with Piranesi and Pannini, encounters that were to have a crucial effect on the development of the art of his maturity.

In July 1766, shortly after his return from Italy, he was admitted to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture and his career began to take off. Specialising in the genres of landscape and capriccio, he regularly exhibited at the Salon du Louvre and soon attracted a large and wealthy clientele who gave him many commissions, including some important ones from royal quarters. Success never left him, at least until the French Revolution, when he lost many of his patrons.

Capriccio

When Hubert Robert was admitted to the Académie, it was as a ‘painter of architecture’, a description that now might seem rather reductive, far from doing justice to the artist’s profuse pictorial output.

A productive painter and draughtsman, master of variations on a theme, he was skilled in all formats, from small panels to large decorative canvases.

Inspired by his Roman tour, he was known as the painter of ruins and monuments ravaged by time, reflecting Diderot’s ideas about capturing the ‘poetic’ in them, which he did to great effect. This fascination with ruins, which consumed art lovers, collectors and painters in the second half of the century, opened the way for Romanticism, but also sounded a prophetic knell just before the collapse of the Ancien Régime.

Hubert Robert orchestrated all his motifs – crumbling temples, half-buried statues, colonnades engulfed by climbing plants and brambles – with endless diversity and a rarely equalled felicity, creating theatrical scenes populated by more contemporary figures of fantasy: shepherds and shepherdesses, washerwomen, livestock and horsemen…

The two paintings from the Ribes collection are among the most perfect examples of capriccios of ruins produced by the artist in the 1770s and 1780s.

Painted as pendants, the first shows a morning with a clear sky and a rural landscape containing antique ruins: in the background there is a temple whose portico recalls the Pantheon. In the foreground, a majestic and grandiose fountain, its architecture inspired by the Arch of Septimius Severus, is the focus of activity for the figures gathered around it. A niche in the centre of the fountain contains a statue of Jupiter, at whose feet a river god and a nymph empty an urn, filling the great basin with the clear water that the washerwomen have come to fetch. The scene is peaceful and serene.

The second painting depicts a sunset, with the warm light of a blazing sky flooding an imposing architectural complex in marked perspective, with arches, fountains, stairways and colonnades, which seem to disappear towards the horizon in the manner of Piranesi.

In each of the paintings, Robert demonstrates an impressive mastery of the composition. The balance is perfectly controlled, the distribution of elements is carefully considered, the relationship between the figures and the landscape and architecture surrounding them is natural. Although they were originally intended for the decoration of a drawing room, the artist goes beyond the decorative and anecdotal to reach the poetry that Diderot was calling for. Hubert Robert evokes a lost fantasy world that still touches the modern viewer, despite the passing of the centuries.

From one Salon to another: from Madame Geoffrin to the Rue de la Bienfaisance

The provenance of a work by Hubert Robert still in private hands has rarely benefited from such prestigious and precisely documented origins. Such paintings rarely come on to the market, and these two examples have not been seen since they were last sold in 1961.

Detailed records in the catalogue of Comte de la Bedoyère’s sale in 1921, written by Catroux, confirm that the two works are those that Madame Geoffrin (1699-1777) commissioned directly from the artist, probably in 1771 or 1772, along with a third, The Forest of Caprarola (presents whereabouts unknown; fig. 1). The collector herself described the circumstances of the commission in her journal: ‘I began my collection of paintings in 1750. They were all made before my eyes.’ She goes on to describe in detail the various works she commissioned from Hubert Robert, including ‘three large paintings of fabriques and landscapes to replace the three large Van Loo paintings that I sold to the Empress of Russia’. Two of these paintings of ‘fabriques and landscapes’ (as compositions representing imaginary architecture were described in France at that time) are the present works. For this significant commission, Robert received the considerable sum of 2760 livres.

Marguerite Gérard has only recently emerged from behind the figure of her brother-in-law Jean-Honoré Fragonard, restoring her to her rightful place in the history of French painting at the turn of the 19th century. On Gérard’s arrival in Paris in 1775, Fragonard quickly took her under his wing, and they collaborated on a number of works including The Interesting Student (estimate: €300,000-€400,000). One of her most accomplished compositions, the painting invites reflection on the nature of the artistic relationship between Gérard and her brother-inlaw and teacher, Fragonard (who painted the white cat).

Lot 18. Marguerite Gérard (1761 - 1837) & Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732 - 1806), L'élève intéressante (The Interesting Student). Oil on canvas, 64,6 x 55 cm ; 25½ by 21⅔ in. Estimate: 300,000 € - 400,000 €. Courtesy Sotheby's.

Revolutionary seizure during his exil in italy and transport of the collection to Nesle's depot (Arch. nat., F17*372, 8 avril 1794 [19 germina an III]; Acquired by Antoine-Gabriel Aimé Jourdan, fermier of the cristallerie de Saint-Louis, with part of the collection stored at the Nesle's depot (Arch. m. nat., Registre de Réception des objets d'art et antiquités trouvés chez les Emigrés et condamnés, réservés par la Commission temporaire des Arts adjoints du Comité d'Instruction publique, 1 DD 6);

Sale Jourdan, Paris, 4 avril 1803 [ Alexandre-Joseph Paillet et Hippolyte Delaroche), n° 18 (Marguerite Gérard), sold 505 francs.

- Collection of Joseph François Xavier Le Pestre, Comte de Seneffe de Turnhout, Paris;

- Seized from the Temple on 8 April 1794 [19 Germinal Year III] by the revolutionary authorities, along with other works belonging to the same prince, and sent to the Hôtel de Nesle, Rue de Beaune;

- Transferred on the orders of the Interior Minister to Antoine Gabriel Jourdan (1740-1804), ‘farmer’ from the Müntzthal national glassworks in Lorraine;

- Jourdan sale, Paris, 4 April 1803 (Alexandre-Joseph Paillet and Hippolyte Delaroche), lot 18 (Marguerite Gérard), sold for 505 francs;

- By descent to his godson, Aimé Gabriel d’Artigues (1773-1848), director of the Saint-Louis glassworks;

- His daughter Anne Gabrielle d’Artigues (1833-1889), who in 1853 married Comte Charles-Édouard de Ribes (1824-1896), mayor of Belle-Église (Oise);

- Their son, Comte Charles-Aimé-Auguste de Ribes (1858-1917);

- His son, Comte Jean-Édouard de Ribes (1893-1982);

- His son, Comte Édouard-Auguste-Édouard de Ribes (1923-2013);

- The current owners.

Exhibited: - Petits Théâtres de l'intime – La peinture de genre française entre Révolution et Restauration, Toulouse, Musée des Augustins, 2011-2012, p. 90-91, n° 19

Literature: - L. Tuetey, « Procès-verbaux de la Commission des monuments (1790-93), Nouvelles Archives de l'Art français ». Revue de l'Art français ancien et moderne, t. XVII, 1901. Société de l'Histoire de l'Art français, 1902, p. 338

- Doin, « Marguerite Gérard (1761-1837) », La Gazette des Beaux-Arts, décembre 1912, p. 436

- S. Wells-Robertson, Marguerite Gérard, Ph. D, New-York University, 1978, pp. 750-751, n°17

- S. Wells-Robertson, "Marguerite Gérard et les Fragonard », Bulletin de la Société de l'Histoire de l'Art français, 1979, p. 184

- J.-P. Cuzin, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Vie et oeuvre. Catalogue complet des peintures, Fribourg, 1987, p. 355, n° D212 "(Marguerite Gérard (et Fragonard?)"

- G. Scherf, « Problèmes d'attribution : Marbres de Falconet, Tassaert et Broche », dans cat. exp. Falconet à Sèvres 1757-1766, Sèvres, Musée national de Céramique de Sèvres, 2001-2002, note 21 p. 44

- J.-P. Cuzin, "Fragonard en 2006", dans cat. expo. Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732 - 1806), Barcelone, 2006-2007, p. 201 (vers 1785-1786, "Fragonard et Marguerite Gérard?")

- C. Blumenfeld dans cat. exp. Marguerite Gérard – Artiste en 1789, dans l'atelier de Fragonard, Paris, musée Cognacq-Jay, 2009, p. 19

- C. Blumenfeld, Marguerite Gérard et la peinture de la fin des années 1770 aux années 1820, thèse de doctorat, Lille, 2011, p. 32, n° 27

- C. Blumenfeld, Marguerite Gérard, 1761-1837, Montreuil, 2019, n° 25 P, repr. p. 26. Sur le processus de collaboration par morceaux, voir texte p. 42, sur le sujet p. 27-31

Note: Only recently has Marguerite Gérard’s name re-emerged from the long shadow cast by her brother-in-law, Jean-Honoré Fragonard. It took a lengthy and patient process of rehabilitation before she at last found her well-deserved place in the history of French painting between the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century.

The gradual reconstruction of her œuvre, thanks to the work of Sally Welles-Robertson, Jean-Pierre Cuzin and more recently Carole Blumenfeld, has allowed us to rediscover this major female artist.

Born in 1761, Marguerite Gérard left Grasse in 1775 for Paris, where she joined her sister Marie-Anne, who had married Fragonard. He quickly took his sister-in-law under his wing and trained her, at first in drawing and printmaking. In 1778 she put her name to her first print, The Swaddled Cat. But her talent as a painter grew rapidly and before long she was able to collaborate with Fragonard himself, contributing to varying degrees to paintings that they produced together.

Meanwhile, her own individual artistic style evolved, soon becoming distinct from her brother-in-law’s art. She developed her own themes and idioms, which assured her success far into the early decades of the nineteenth century.

The Interesting Student was the subject of a well-known 1787 engraving by Géraud Vidal (1742-1801; fig. 1) and numerous copies of it exist. The painting features one of the young Marguerite Gérard’s most accomplished compositions – if not the most accomplished, despite coming so early in the artist’s career. In later years she rarely achieved such felicity in her composition and such refinement in her technique.

L’élève intéressante, gravure par Géraud Vidal, 1787

Marguerite drew inspiration from various sources for this painting, but her principal influence was the Dutch painting of the Golden Age, especially that of the fijnschilders, the painters of everyday life and intimate interiors, admired for their extremely precise and detailed pictorial technique, as well as for their almost obsessively illusionistic rendering of textiles and surfaces. Emulating the development of her brother-in-law’s art in the years 1770 -1780, Marguerite Gérard turned her gaze towards painters such as Gerard ter Borch, Gabriel Metsu and Frans van Mieris the Elder, drawing from their examples her delicate and precise technique and her taste for interior scenes. Along with Louis-Léopold Boilly, her exact contemporary, she was one of the first to encourage the fashion for such themes.

Marguerite was only twenty-six years old when she painted The Interesting Student, her first major canvas, but in it she demonstrated that she had completely mastered her pictorial technique. The delicate treatment of fabrics, the fluidity of their folds and the lustre of the young woman’s satin dress, as well as the rendering of surfaces and the shine of the metal, are all executed with the most perfect eye for detail. The composition is enriched by the dominating presence of a profusion of artworks – sculptures, prints, paintings – and objects of domestic life: from the metal sphere at the bottom left of the canvas (to which we will return) to the two statuettes on the table, from the young woman’s hat casually resting on the sculptural group to the stand on which it is placed. Many of these elements can be found in the artist’s later works, for example the three-legged table on which the sculpture rests. This interesting detail (fig. 2), showing Two Cupids Fighting Over a Heart (or perhaps Love and Friendship, according to an old sale catalogue) reprises a composition that was celebrated in its time, long considered to be the invention of Falconet, but in reality attributable to the brothers Nicolas and Joseph Broche (see G. Scherf, op. cit., note 20 p. 44).

D’après N. et J. Broche, Deux Amours se disputant un cœur ou l’Amour et l’Amitié

The title of the work, The Interesting Student, is known from the inscription on Vidal’s engraving. Although it might have been tempting to see Marguerite Gérard herself in the young woman absorbed in contemplating a print, it seems that such a hypothesis must be discarded: Vidal dedicates his print to ‘Mlle Chéreau’, and the monogram ‘AC’ appears in the centre of the inscription, surrounded by a wreath of flowers. These elements suggest that the young woman portrayed is in fact Anne Louise Chéreau, born in 1771 and herself from a family of engravers and print publishers.

At first sight, the painting’s subject matter is very simple, but it is possible that it conceals a deeper meaning. Through its title, The Interesting Student, through the elements disposed in the room, and through the metal sphere at the bottom left, Marguerite Gérard appears to be presenting the viewer with a puzzle that must be decoded. The print that Anne Louise Chéreau is holding is not insignificant: it is a print of Fragonard’s Fountain of Love, executed by Regnault in 1785 (fig. 3), which was widely admired. The theme of love is also evoked in the sculptural group by the Broche brothers. Finally, the sphere of polished steel placed on the ground on top of a crumpled print, whose model is difficult to identify (fig. 4), acts as a mirror in the painting, reflecting an image of the rest of the room and four figures including Marguerite Gérard herself, sitting at her easel with her master and mentor Fragonard behind her. The remaining two figures have been identified as Marie Anne Fragonard and Henri Gérard or perhaps the engraver Géraud Vidal himself.

Gravure par Regnault d’après J. H. Fragonard, La Fontaine d’Amour, 1785.

Détail du lot 18.

Looking beyond its purely technical qualities, The Interesting Student once again raises the question of the artistic relationship between Marguerite Gérard and her brother-in-law and master, Fragonard. Leaving aside the possibility that has sometimes been suggested of an intimate relationship between the master and his charming young sister-in-law, the theory that the two painters collaborated on many of Marguerite’s early paintings has frequently been proposed. It now seems to be accepted that Fragonard, in the first paintings produced by his young sister-in-law and pupil, must often have assisted with the design of their composition as well as supplying one or more details. In a mischievous vein, Fragonard was responsible for the white cat (which he had already added to an earlier painting by Gérard, The Angora Cat) teasing the dog lying on a stool covered in blue velvet. Is this perhaps an allusion to a marked complicity that went further than a simple artistic collaboration?

One of Jean-Baptiste Leprince’s most accomplished paintings, The Futile Lesson from 1772 (estimate: €150,000-€200,000) was commissioned by the Duke of Choiseul-Praslin and was exhibited at the Salon the following year. Inspired by Dutch genre painting from the previous century, the theatrical work depicts a domestic scene being played out in a luxurious bedroom, as a young girl’s letters and portraits from her suitor have been discovered by her parents.

Lot 21. Jean-Baptiste Leprince (1734 - 1781), The Futile Lesson. Oil on canvas; signed and dated bottom left: Le Prince 1772, 73,2 x 92,5 cm ; 28 3/4 by 36 1/3 in. Estimate: 300,000 € - 400,000 €. Courtesy Sotheby's.

Provenance: - Collection of duc Renaud César Louis de Choiseul-Praslin (1735-1791) ;

- His sale, Paris, 18-25 February 1793, lot 170, with its pendant, « Le médecin aux urines » (adjudicated 861 pounds to Gendrier) ;

- Collection Aimé Gabriel d'Artigues (1773-1848), director of the Saint-Louis glassworks ;

- His daughter Anne Gabrielle d'Artigues (1833-1889), who in 1853 married Comte Charles-Édouard de Ribes (1824-1896), mayor of Belle-Église (Oise) ;

- Their son, comte Charles-Aimé-Auguste de Ribes (1858-1917) ;

- His son, le comte Jean-Édouard de Ribes (1893-1982) ;

- His son, le comte Édouard-Auguste-Édouard de Ribes (1923-2013) ;

- To current owners.

Exhibited: - Paris, Salon of 1773, n°54 with the following description : Une mère, ayant surpris une cachettte qui renferrmait un portrait, des lettres et des bijoux, faits les plus vifs reproches à sa fille, qui malgré l'apparence de son repentir, reçoit encore une lettre qu'une servante lui donne en cachette; le père cherche à lire les sentiments de sa fille dans ses yeux, tandis que la grand-mère lit une de ces lettres

Literature: - Eloge des tableaux exposés au Louvre, Paris, 1773, p. 42-43

- L.-P. de Bachaumont, Mémoires Secrets pour servir à la République des lettres, Lettre II, 14 septembre 1773 (éd. 1995, p. 41)

- Le Mercure de France, octobre 1773, t. I, p. 169

RELATED WORK: Engraving by Isidore Stanislas Helman (1743-1806) from 1781, titled The Futile Lesson (fig. 1)

French Royal bronzes

Having been part of the Royal collections until the Revolution, two rare bronzes from the collection of Louis XIV are set to be offered at auction for the very first time.

Presented in 1796 as payment to the state contractor Gabriel Aimé Jourdan, these two exceptional school of Giambologna masterpieces, Rape of a Sabine and Fortuna, are both attributed to Antonio Susini (1558-1624) – the principal bronze-caster to the Florentine master and an important Mannerist sculptor in his own right – during Giambologna’s lifetime.

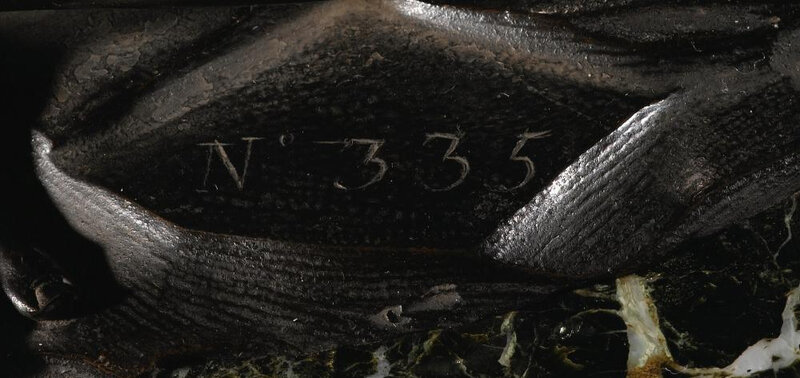

Rape of a Sabine, attributed to Antonio Susini, after Giambologna (1529-1608), circa 1590-1610 (estimate: €2.5-5 million), is considered one of the oldest and finest casts of this model – the original of which is one of the architectural glories of the Late Renaissance in Florence. Magnificently detailed, it is engraved with the number 335 in the inventory of the French Royal Bronzes and was exhibited for the last time in 1956 – before its significance was truly known.

Lot 14. Attributed to Antonio Susini (1558-1624), the model by Giambologna (1529-1608), Italian, Florence, circa 1590-1610, Rape of a Sabine, bronze, brown patina; on an associated sea green marble and gilt-bronze mounted socle, French, early 19th century, engraved on the terrace : N° 335, the bronze: 59,5 cm; 23 1/4 in. Estimate 2,500,000 — 5,000,000 EUR. Courtesy Sotheby's

Provenance: - In the inventory of the Grand Dauphin, Versailles, 1689, no. 28 or 29 (see also the French Royal Bronze N° 331, another « Enlèvement »)

- in the diary of the Garde-Meuble royal, Hôtel of the Petit-Bourbon, Paris, 1738 (as coming from Versailles, « l'enlèvement des Sabines »)

- in the inventory of the new Garde-Meuble royal by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, Louis XV Place (currently Place de la Concorde), Paris, 1775

- mentioned as « mis en couleur de fumée » by Pierre Gouthière (1732-1813), 1785-1786

- in the inventory of appartments of Marc-Antoine Thierry, Baron of Ville-d'Avray (1732-1792), Versailles, 1788

- ibidem, 1791

- delivered to Gabriel Aimé Jourdan, on 2 Fructidor of the Year IV (19 August 1796)

- in the inventory of the estate of his godson, Aimé Gabriel d'Artigues, by Me Turquet, assisted by Me Sibire, auctioneer, and S. Mannheim, expert, 1848 (no 167).

LITERATURE: - Inventaire des diamans de la Couronne, perles, pierreries, tableaux, pierres gravées, Et autres Monumens des Arts & des Sciences existants au Garde-Meuble, par les commissaires MM. Bion, Christin & Delattre, Députés à l'assemblée nationale, suivit d'un rapport sur cet Inventaire, par M. Delattre, Paris, 1791

- Le Cabinet de l'amateur, exh. cat. Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, 1956, no. 199 (described as the Enlèvement d'Orithye)

- S. Castellucci, « La collection de bronzes du Grand Dauphin, in Curiosité. Etudes de l'histoire de l'art en l'honneur d'Antoine Schnapper, Paris, 1998, pp. 355-363

- S. Baratte, G. Bresc-Bautier, Les Bronzes de la Couronne, exh. cat. musée du Louvre, 1999, p. 24 (mentioned in the footnote no. 19) and p. 186

- P. Wengraf, Renaissance & Baroque Bronzes from the Hill Collection, Londres, 2014, pp. 148-156 (same height than the Nos. 186 and 187, mentioned in footnote no 11)

RELATED LITERATURE: - B. Sermartelli, Alcune Composizioni di diversi autori in lode del ritratto della Sabina, Florence, 1583

- G. P. Lomazzo, Trattato dell'arte della Pittura, 1584

- F. Baldinucci, Notizie dei professori del disegno da Cimabue in qua, book 3, Florence, 1681-88, pp. 7, 89

- R. Weihrauch, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum München, Band XIII, 5, Die Bildwerke in Bronze und in anderen Metallen, Munich, 1956, pp. 84-87, cat. 110

- K. Watson and C. Avery, 'Medici and Stuart: a Grand Ducal Gift of 'Giovanni Bologna' Bronzes for Henry, Prince of Wales (1612)', The Burlington Magazine, 115, 1973, pp. 493-507

- Die Bronzen der Fürstlichen Sammlung Liechtenstein, exh. cat. Museum Alter Plastik, Frankfurt, 1986, p. 177, cat. 16

- M. Leithe-Jasper and P. Wengraf (eds.), European Bronzes from the Quentin Collection, exh. cat. Frick Collection, New York, 2004, pp. 166-173

- P. Wengraf, 'Zur Bedeutung der "Signaturen" an Giambolognas Marmor -und Bronzefiguren', in W. Seipel (ed.),Giambologna. Triumph des Körpers, exh. cat. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 2006, pp. 102-139

- D. Zikos, 'Die Dresdner Giambolognas. Apologie ihrer Eigenhändigkeit', Giambologna in Dresden. Die Geschenke der Medici, exh. cat. Grünes Gewölbe, Dresden, Munich, 2006, pp. 89-94

- W. Seipel (ed.), Giambologna. Triumph des Körpers, exh. cat. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 2006, pp. 120f., pp. 273-275

- D. Zikos, 'Giovanni Bologna and Antonio Susini: an old problem in the light of new research' in P. Motture, E. Jones and D. Zikos (eds.), Carvings, Casts & Collectors. The Art of Renaissance Sculpture, London, 2013, pp. 194-209

- P. Wengraf (ed.), Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes from the Hill Collection, London, 2014

- C. Kryza-Gersch, 'Antonio Susini Rape of a Sabine' in P. Wengraf (ed.), Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes from the Hill Collection, London, 2014, pp. 148-155

- D. Zikos, 'A bronze group of the Rape of a Sabine by Giambologna', in The Exceptional Sale, Christie's, London, 10 July 2014, lot 30, pp. 134-141

- D. Zikos, 'Raub einer Sabinerin (nach Giambologna)', in J. L. Burk (ed.), Bella Figura. Europäische Bronzekunst in Süddeutschland um 1600, exh. cat. Bayerischen Nationalmuseum, Munich, 2015, pp. 200-203

Note: Un grouppe (sic) de l'enlèvement d'Orithye de vingt-un pouces et demi de haut [58,2 cm], estimé quinze cent livres." (cf. Inventaire des diamans [...], 1791, op. cit., p. 186)

This exquisitely cast and chased bronze is engraved with the Royal inventory number 335. It was last exhibited in 1956, at which time its significance was not fully recognised. The emergence of the Ribes Sabine onto the art market provides an opportunity to reassess its importance, and underline its status as one of the prime casts of this seminal Florentine late Renaissance model.

Giambologna's Rape of a Sabine: The Creation of an Icon

Artistic rivalry has often inspired great creative achievements. This holds true for Giambologna’s marble group of the Rape of a Sabine, one of the glories of late Renaissance Florence (fig. 2). The unveiling of the marble in January 1583 was surely an exciting event, because the group was installed, but kept under wraps for six months whilst Giambologna added the masters final finish to the surface – his ultima mano – hidden from public gaze. This spiraling, dynamic composition took the place in the Loggia dei Lanzi of Donatello’s late masterpiece in bronze, Judith and Holofernes, which was moved to a more exposed location in the Piazza della Signoria (Kryza-Gersch, op. cit., p. 150). It is not known if Giambologna thought his marble rivalled Donatello’s bronze, but we can be more certain that he was conscious of his being judged against the legacy of Michelangelo. As an old man Giambologna is said to have recalled an episode in his youth when as a student in Rome he approached Michelangelo with a wax model he had diligently worked to great refinement (Baldinucci, op. cit.). Michelangelo is said to have taken the modello in his hand, crushed it, rapidly remodeled it and returned it to the young sculptor instructing him to go and learn the art of modelling before he practised the skill of finishing. Now in his fifties, Giambologna was able to unveil a triumph in marble carving that had eluded even the seminal genius of Michelangelo: a monumental three figure group which epitomised the older sculptor’s vision for a multi-figure composition – ‘there is no better form than that of a flame, because it is the most mobile of all forms and is conical. If a figure has this form it will be very beautiful. The figure should resemble the letter 'S' (Lomazzo, op. cit.).

Giambologna (1529-1608), L’Enlèvement d’une Sabine, marbre, Loggia dei Lanzi, Piazza della Signoria, Florence

The unveiling of the Rape of a Sabine inspired spontaneous poetic eulogies, immediately compiled in a volume by Bartolomeo Sermartelli (op. cit.). The nobleman Bernardo Davanzati described it as ‘the glory of all divine art embodied in a triform statue, an ideal and paradigm for all great artists’ (ibid., p. 7). Inevitably, collectors across Europe wished to acquire copies of this renowned work, and the shrewd Medici knew how to capitalize on the fame of their court sculptor. For example, in 1610 Henry Prince of Wales, the elder brother of Charles I, singled out the Rape of the Sabine in his request for models after Giambologna as part of the marriage negotiations for the union with Caterina de’ Medici, the sister of Cosimo II: 'et amerebbe d'haver fra l'altri nella soprad.a picciolezza quel ratto delle sabine, che e nella gran Piazza di Firenze', ('and amongst others I would like to have a small Rape of a Sabine which is in the great Piazza in Florence' - Watson, Avery, op. cit., p. 505). A visual testimony to the primacy of the Rape of a Sabine is shown in a version of Jan Breughel the Younger’s allegorical painting of Sight, dating to around 1660, which shows a large gilt bronze version at the centre of the composition (see Sotheby’s, A selection from Old Masters. A brush with Nature, Hong Kong, 2018, fig. 3).

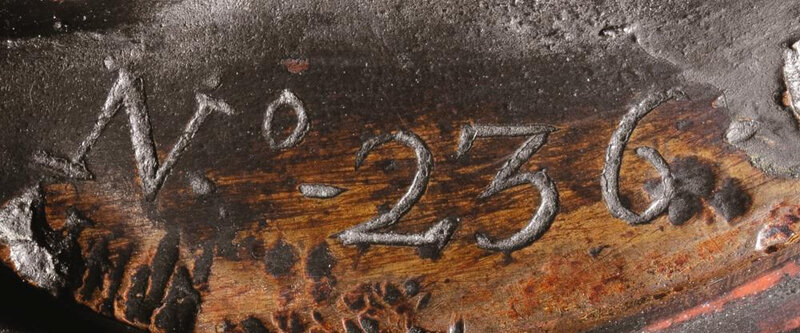

A further exceptional cast attributed to Antonio Susini, after Giambologna, circa 1580-1600, Fortuna (estimate: €1-2 million) has never previously been shown to the public. Comparable with the model held in the collection of the Louvre, it is one of the most beautiful versions known of this cast and is also numbered in the royal inventory.

Lot 15. Attributed to Antonio Susini (1558-1624), the model by Giambologna (1529-1608), Florence, circa 1580-1600, Fortuna, bronze, light brown patina ; on a red griotte marble base with gilt bronze mounts, French, circa 1796-1800, the bronze engraved on the terrace N° 236(bronze) 47,3 cm; 18 5/8 in. ; (totale) 63 cm ; (overall) 24 4/5 in. Estimate 1,000,000 — 2,000,000 EUR. Courtesy Sotheby's.

Provenance: - 1689, legacy of the painter Charles Errard (1606-1689), ), first director of the Académie de France in Rome from 1666 to 1673

- 1707, in the inventory of the royal Garde-Meuble, Hôtel of Petit-Bourbon, Paris

- 1722, ibidem

- 1733 , ibidem

- 1775, in the inventory of the new royal Garde-Meuble by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, Louis XV Place (currently Place of the Concorde)

- 1778, ibidem, exhibited in the Gallery of the Bronzes

- 1791 , ibidem

- 1796, delivered to Gabriel Aimé Jourdan, on 2 Fructidor of the Year IV (19 August 1796)

- 1803, sale by Me Lemonnier, assisted by A-J. Paillet and H. Delaroche, Paris, 4 April 1803, lot 90, bought by Glaise

- 1848, in the inventory of the estate of Aimé Gabriel d'Artigues (1773-1848), god son of Gabriel Aimé Jourdan, by Me Turquet, assisted by Me Sibire, auctioneer, and S. Mannheim, expert (no. 141).

Literature: SOURCE

- Livraison à Jourdan le 2 Fructidor de l'an IV, A. N. O 1 3376.

LITERATURE

- Inventaire des diamans de la Couronne, perles, pierreries, tableaux, pierres gravées, Et autres Monumens des Arts & des Sciences existants au Garde-Meuble, par les commissaires MM. Bion, Christin & Delattre, Députés à l'assemblée nationale, suivit d'un rapport sur cet Inventaire, par M. Delattre, Paris, 1791, p. 226

- K. Watson, Ch. Avery, "Medici and Stuart: a Grand Ducal Gift of Giovanni Bologna Bronzes for Henry Prince of Wales", in Burlington Magazine, CXV, 1973, pp. 493-507

- Ch. Avery, A. Radcliffe, Giambologna 1529-1608, Sculptor to the Medici, exh. cat. Edinborough, Londres, 1978 et Vienne 1979, pp. 69–71, no. 13-16

- B. Jestaz, "La statuette de la Fortune de Jean Bologne", in Revue du Louvre et des musées de France, 1978, XXVIIIth year, pp. 48-52 Ch. Avery, Giambologna. The complete Sculpture, London, 1993, p. 136, no. 57

- W. Seipel, Giambologna, Triumph des Körpers, exh. cat. Vienna, 2006, pp. 273-275.

- D. Zikos, 'Giovanni Bologna and Antonio Susini: an old problem in the light of new research', dans Carvings, casts & collectors. The art of Renaissance Sculptors , Londres, 2013, pp. 194 – 209.

Note: 'A standing female nude, holding in each hand a type of rolled-up cloth, and looking at the cloth held in her raised left hand; her feet resting on a small oval bronze base: height seventeen and a half pouces [47.3 cm], from the socle to the end of the left arm, modern bronze, estimated value 600 livres’ (see Inventaire des diamans [...],1791, op. cit., p. 226).

The Fortuna from the Ribes collection is of exquisite quality and one of the most beautiful of the known bronze versions of this model. Once in the French Royal Collection, and delivered to Jourdan in 1796, the statuette was in the d’Artigues collection and remained in the family from the beginning of the nineteenth century – certainly well before 1848. It has never been shown in public.

Documents brought to light by Avery and Watson demonstrate the existence of a Fortuna in the collections of Lorenzo Salviati and Benedetto Gondi, close friends of Giambologna, enabling the subject to be identified as a work by the sculptor, executed for the first time between 1565 and 1570 (see Ch. Avery, K. Watson, op. cit., 1973, p. 502-504). A statuette of Fortuna is indeed mentioned in the 1609 inventory drawn up after the death of Lorenzo Salviati, numbered 1084 and described as an ‘invention’ of Giambologna, cast – like the present bronze – by Susini ‘… A small bronze female figure, its height around 2/3 of a braccio, … by the afore-mentioned Susini … these ten bronzes come from Gio. Bologna’.

Antonio Susini (1558-1624) was one of the most important sculptors and bronze-casters in Florence to have worked in Giambologna’s atelier (1529-1608). Along with his master, he is the most emblematic artist of Italian Mannerism. After training as a goldsmith, Susini was employed in casting and making moulds in Giambologna’s workshop, becoming his most important assistant. After Giambologna died in 1608, Susini opened his own workshop where he made bronzes after his master’s models. These were sought after for their high quality: known for the precision of their casting and the exquisite chasing of their surface finish, the refinements of Susini’s bronzes was indeed superior to those produced by his master.

Among the published versions, the Fortuna in New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. no 24.212.5) and the version in Stanford (inv.no 62.235) are considered to have been cast in the seventeenth century after Giambologna’s model. This subject is rare, and there are known variants showing Fortuna poised on a globe (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (inv.no.1970.57), or appearing as Venus Marina standing on a seashell, where she holds in her hands the ends of a sail billowing in the wind (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; inv.no.PL5885). The example once in the Uzielli collection in London, formerly in the collection of the Marchese della Gherardesca, reprises this same composition (see Ch. Avery, op. cit., 1978, no. 16). Another bronze depicting exactly the same subject is described in the inventory of the collections of King Charles I of England, in 1640. Given in 1612 to Henry, Prince of Wales (1594-1612) by the Grand Duke of Tuscany, this cast would appear to have been commissioned from Pietro Tacca and is described as: ‘a standing woman with her left hand over her head and the other down to hold a fortune’s veil’ (see Ch. Avery, K. Watson, op. cit., p. 506).

One of the first Renaissance depictions of Fortuna appeared in 1551 in an engraving of ‘Ars naturam adiuvans’, book 98 of Andrea Alciati’s Emblemata (fig. 2). Giambologna may have been inspired by this iconography showing Fortuna in a similar pose, here blindfolded with long hair blown by the wind but with the same swaying stance, standing on a globe opposite Mercury. As Avery suggests, Fortuna seems to have been created by Giambologna to form a pair with his famous Mercury, the first model of which dates to 1563. Indeed, the entries for Mercury and Fortuna follow each other in the 1609 Gondi collection inventory. The figures' body postures seem to reflect each other, their gestures are closely complementary. An association between these two figures goes back to antiquity, a popular theme being the opposition between chance (Fortuna), apparently holding sway over human affairs, and the ingenuity (Mercury) that human beings could deploy in their activities.

Andrea Alciati, Ars naturam adiuvans, dans Emblemata, gravure, 2e éd. Lyon, 1551.

The present exceptional cast of Fortuna has all the attributes of a bronze made by Antonio Susini. The Ribes Fortuna can be considered with the version in the Louvre, - engraved with no. 68 from the French Royal collections - as one of the best published examples of this model. Already Jestaz acknowledged the Louvre Fortuna as a cast made by Antonio Susini during Giambologna’s lifetime (inv.no.OA10598; op.cit. 1978, p.52). The Louvre version can be distinguished from our bronze by its engraved irises, whereas in the Ribes bronze the eyes are left blank.This feature appears generally in casts made by Antonio Susini in the late 1580s, after 1587 (D. Zikos, op.cit, p. 196-198). The absence of this detail in the Ribes Fortuna, where the irises are not incised, likely indicates that our bronze may be slightly earlier than the Louvre example. In fact, it may therefore be considered as one of the earliest known versions of this model.

The Ribes Fortuna is remarkable for the superlative quality of the casting: each detail is rendered with great precision. The features of the face and eyes are finely drawn, as well as her ear lobes, the long fingers and the toes with their clearly defined nails, set convincingly in the flesh. Susini’s virtuosity is especially evident in the fine modelling of her hair, divided by a parting at the back and shaped into slender bands of sinuous curls. The chiselling of the evenly wire-brushed surface gives emphasis to the forms of the body and reveals a golden-brown patina, covered with a dark brown translucent varnish.

Bequeathed to Louis XIV by the painter, engraver and architect Charles Errard (1606-1689), first director of the Académie Royale, the present bronze was mentioned as early as 1689 in the collections of the King’s Garde-Meuble. Like Abundance (lot 14), the Fortuna was displayed from 1788 in the Bronzes Gallery of the new Garde-Meuble, designed by Anges-Jacques Gabriel (see the introduction and the catalogue entry for lot 14 for further information). Although the elevation drawing of the south wall by Jean-Démosthène Dugourc (1749-1825) – the architect in charge of the arrangement of the bronzes – shows the statuettes displayed there in reverse (it was probably taken from a tracing), they are nevertheless easily identified. Abundance was destined for the long north wall of the gallery and is therefore absent, but the Ribes Fortuna can be clearly recognised as the fifth bronze to the left of the first left-hand door in Dugourc’s drawing (fig. 3).

Jean-Démosthène Dugourc (1749-1825). Détail du projet de décor pour le mur Sud de la Galerie des Bronzes du Garde-meuble de la Couronne, 1786, musée Carnavalet, Paris.

Decorative arts with historical provenance

The Ribes collection features a rare pairing: a Louis XVI bureau à cylindre by Claude-Charles Saunier with a highly sculptural Louis XIV-era Pendule aux Parques mantel clock attributed to André-Charles Boulle (estimate: €250,000-€500,000). The pair hail from the Stroganov collection in St Petersburg and were acquired by Jean de Ribes at the Soviet sales in Berlin in 1931.

Lot 7. A Louis XVI gilt-bronze mounted ebony 'bureau à cylindre', stamped C.C.SAUNIER and JME, circa 1775; with a gilt-bronze mounted ebony and tortoiseshell 'Parcae' clock, attributed to A.-C. Boulle, late Louis XIV, circa 1710. Estimate 250,000 — 500,000 EUR. Courtesy Sotheby's.

The bureau: with a grey veined marble top, the veneer on each side with satinwood inlay, the cylinder top opening to reveal two satiné, tulipwood, mahogany and amaranth drawers with bone handles and five recesses, above three lower drawers.

The clock: the movement and the dial associated and signed Ageron / A PARIS, the enamels of the dial signed A.N. Martinière, émailleur et penfionnaire du roy 1746; the base of the clock with twisted feet created during the reign of Louis XVI.

The clock and the bureau associated circa 1820.

Le bureau : haut. 116,5 cm, larg. 130 cm, prof. 62 cm ; the desk: height 45¾in., width 51¼in., depth 24½in. ; La pendule : haut. 65,5 cm, larg. 56 cm, prof. 37 cm ; the clock: height 25¾in., width 22 in., depth 14½in.

Provenance: - Collection Counts Stroganov, Stroganov Palace, St. Petersburg;

- Thence Sale Collection Stroganov, Berlin, Lepke Gallery, 12-13 May 1931, lot 217; where bought by Jean, 5th Comte de Ribes (1893-1982).

Literature: - L. Réau, « L'art français du XVIIIe siècle dans la collection Stroganov », in Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de l'art français, 1931, p. 67

RELATED LITERATURE

- H. Demoriane, « Le château que les ducs de Wellington habitent depuis un siècle et demi », in Connaissance des Arts, n°153, November 1964, p. 107

- C. Fontana, « Claude-Charles Saunier, un Ebéniste du Siècle des Lumières », in L'Estampille L'Objet d'art, n° 373, October 2002, pp. 70-82

- C. Frégnac and J. Meuvret, L es Ebénistes du XVIIIe siècle français, Paris, 1963, p. 226, fig. 5 and p. 227

- P. Hunter-Stiebel, Stroganoff, the palace and collections of a Russian noble family, New York, 2000

- P. Kjellberg, « Saunier », in Connaissance des Arts, n° 205, March 1969, p. 81, fig. 11

- J.-N. Ronfort, A ndré-Charles Boulle, un nouveau Style pour l'Europe, exh. cat. Frankfurt, 2009, n° 14, pp. 224-225

- J.-P. Samoyault, André-Charles Boulle et sa famille, Geneva, 1979, pp. 14, 67, 145, 171 and 177

- P. Hunter-Stiebel, Stroganoff, the Palace and Collections of a Russian Noble Family, Texas, 2000.

Bureau à cylindre by Claude-Charles Saunier

Claude-Charles Saunier (1735-1807) was born into an important family of respected cabinetmakers and received his Master cabinetmaker status on 31 July 1752. He shared his workshop at Faubourg Saint-Antoine with his father Jean-Charles, but later moved to Rue Saint-Claude. His production started during the reign of Louis XV, but he is especially known for the resplendent furniture he produced during the reign of Louis XVI. Distinguished by a great Neoclassical simplicity, his creations are exemplified by the delicate stringing which highlight the wooden veneer.

This type of bureau à cylindre (cylinder desk) was notably made by Saunier and several examples decorated in vernis Martin, painted sheet metal or veneer, with the same architectural structure above the cylinder and sometimes with a large circular medallion at the centre of the cylinder are known:

- former Luigi Laura Collection, Sold Sotheby's and Poulain and Le Fur, Paris, 27 June 2001, lot 83 (Parisian varnish), cf. fig. 4;

- former Collection of the Dukes of Mortemart, Sold Sotheby's, Paris, 11 February 2015, lot 104 (painted sheet metal), cf. fig. 6;

Bureau de Saunier, collection des ducs de Mortemart, Sotheby’s, Paris, 11 février 2015, lot 104 © Sotheby’s

- Collection of Nissim de Camondo Museum, Paris, inv. CAM 55 (speckled mahogany veneer)

The gilt bronze ornamentation also holds a prominent place in his styling and we find the same rosette which adorns our cylinder desk on a pair of corner cabinets in the Nissim de Camondo Museum (CAM inv. 125.1 and 2, cf. fig. 5).

Encoignure d’une paire, musée Nissim de Camondo, Paris © Photo Les Arts décoratifs, Paris/Jean Tholance

Saunier collaborated with the marchand-mercier Dominique Daguerre on many pieces of furniture. Daguerre had a list of prestigious clients which necessitated his request and expectation for the highest quality production. Thus, in 1787, the Duc d’Harcourt, Governor of the Grand Dauphin, via Daguerre, took delivery of a secrétaire cabinet stamped by Saunier. Other clients included Comte de Narbonne, Secretary of War under Louis XVI, Jean-Baptiste Roslin d’Ivry and Lord and Lady Spencer.

Mantle clock with Parcae belonging to Monsieur Coustou, by André-Charles Boulle (1642-1732)

Created around 1710-1725, this model is described in his posthumous inventory of 1732 at number 76: “a clock case with Parcae for Mr. Coustou, the cartouche, frames, three figures and a fourth which is the old ... 164 l”. André-Charles Boulle asked the sculptor Nicolas Coustou (1658-1733) to create the three Parcae figures, specifically for this clock.

This mythological theme is an allegory of time, when the three Parcae - sisters born of Erebus and Night, determine the length of Life. Clotho, on the left, spins the thread of Life with her spindle, Lachesis measures it and Atropos, the eldest, cuts it.

The Parcae figures belong to the cabinetmaker’s repertoire as evidenced in his posthumous inventory of 1732 and published by J.-P. Samoyault: “a box containing the models of old [mantle clocks] with Parcae, with support prototypes and culs-de-lampe” and “a [box] containing models of mantle clocks with Parcae with the isolated time”.

The motif of the three gilt bronze Parcae was applied, as with the figures of Aspasia and Socrates, onto medal cabinets and can also be found on the upper part of a cabinet with shelves in the Collection of the Duke of Marlborough at Blenheim Palace, with another in the Wallace Collection in London (inv. F413, see fig. 10).

Finally, our clock not only adopts this theme, but tranforms it as the three Parcae figures are sculptured in the round, thus different from the models which used relief carved panels.

Among the copies listed, with some variations, we can cite:

- a model fitted with an ebony plinth like the one presented during the Boulle exhibition in Frankfurt, no. 14. An example bought by the Duke of Wellington around 1960 for the Stratfield Saye House is fitted with a central cartouche on the plinth (op. cit. Connaissance des Arts, nov. 1964, p. 107);

- a model without a plinth on a filing cabinet, one of which is kept at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore and one in the Wallace Collection, London (see P. Hughes, Wallace Collection Furniture Catalogue, vol. 2, pp. 696-706, fig. 10);

Pendule aux Parques d’après A.-C. Boulle, Collection Wallace, Londres © Wallace Collection, London, UK / Bridgeman Images

- a model entirely in gilt bronze auctioned by Sotheby's Paris, on 5 July 2001, lot 18;

- a model fitted with a barometer and spiral fluted feet. A mantle clock cited in the posthumous inventory of Mr. Eustache Bonnemet established 6 September 1771, no. 126 (A.N. Min XLV);

This last model could relate to our clock which had its movement and its dial changed after 1771, the date of the Bonnemet Collection auction. The placement of the clock on our desk is difficult to date and could have taken place during the 1770s, a period which was known for the rekindling of Boulle works, recreated by the great cabinetmakers Adam Weisweiller and Étienne Levasseur. However, it seems more likely that the affiliation took place in France, or Russia during the 1820s. Perhaps at this time, the Louis XV dial and the movement, signed by François Ageron (master clockmaker status in 1741), was also inserted into the Louis XIV casement with the Parcae. The spiral feet to the base, although resembling a Louis XIV aesthetic, typical on certain Boulle clocks (see Frick collection, New York, inv. 1999.5.148 and Château de Versailles, inv. O 117.1) is a creation from the reign of Louis XVI, and thus earlier than the placement of the mantle clock onto the cylinder desk.

This mantle clock model is found without precise description in several important 18th century collections:

- a mantle clock adorning a wardrobe’s lower part by Pierre Gruyn in 1722;

- another is described by the decorative arts dealer Thomas-Joachim Hébert in 1723;

- one featured on a Samuel Bernard desk;

- two were kept at Paul-Louis Randon's house in Boisset, one with astronomical signs;

- one would have been offered by Louis XV to the Marquis de Puyzieulx, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs from 1747 to 1751.

Count Alexander Sergeyevich Stroganov (1733-1811)

Alexander Sergeyevich was born in 1733 (fig. 1) into a powerful family from Novgorod, who occupied an area in the Ural Mountains during the 16th century and mined its fabulous ore deposits.

A. Roslin, Portrait du comte Alexandre Stroganoff, 1772, Palais Stroganoff, The State Russian Museum, Saint-Pétersbourg © The State Russian Museum, Saint-Pétersbourg

In 1768, Sergeyevich participated in the founding of the Imperial Academy of Arts. He first married Anna Vorontsova in 1758, and in 1771 he married Ekaterina Trubetskaya. He undertook a second trip to Europe and settled in Paris in Rue de Richelieu, moved to Rue Montmartre and finally settled in Rue de Verneuil. His two children Pavel Alexandrovich and Sofia were born in Paris.

Passionate about the arts, he built one of the most important collections of paintings, buying from the most prestigious auctions of the time. He commissioned paintings by Hubert Robert and Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, busts of Voltaire and Diderot by the sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon, a pair of ebony consoles after a very original design by the cabinetmaker Jacques Dubois and also from the widow Dulac, Rue Saint-Honoré. He notably owned the pair of vases from the former Anton Luigi Laura Collection (Sotheby's Sale, Paris, 27 June 2001, lot 76). According to the art historian and curator Otto von Falke (1862-1942), who wrote the preface for the Stroganov auction in 1931, it appears that “Count Stroganov had a predilection for ebony with strong contrasts of gilt bronze. Almost all the Louis XVI furniture in the palace is clad with this wood type and comes from the best cabinetmakers such as Martin Carlin (...)”. He also listed as belonging to the Count, “Saunier's cylinder desk with the pendulum (lot 217)” (fig. 8).

In 1801, Tsar Paul I appointed Count Stroganov to the Construction Supervisory Board of the Cathedral of Our Lady of Kazan.

The Stroganov Palace

The Stroganov Palace, in the heart of St. Petersburg on Nevsky Prospect, known as one of the jewels of St. Petersburg architecture, was built by the architect Francesco Batolomeo Rastrelli in 1753, (fig 2). He was also responsible for the Winter Palace. Distinctly influenced by the Italian Baroque, the Palace during its construction, had a Baroque decor similar to those found in churches in Bavaria. When the Count returned to Russia, he undertook a reconstruction of the Palace which entailed both expansion and a renovation in the ‘antique’ style. In around 1790, the famous picture gallery and the mineralogical cabinet were built (fig. 7).

Vue du palais Stroganoff, Saint-Pétersbourg

Vue du bureau dans la cabinet minéralogique du palais Stroganoff, vers 1931

Soviet Auctions

In 1914, Sergei Alexandrovich (1852-1923), last Count of the Stroganov dynasty decided to open the Palace to the public. Four years later, the Bolsheviks occupied the fourth floor of the Palace, which in 1919 became a museum in the city of Petrograd and was subsequently annexed to the State Hermitage Museum. The Soviet government, proprietor of the contents, began to disperse the collection. This desk was relinquished by the Soviet Union during large auctions of the artworks between the two World Wars, in order to finance industrial development. The lack of liquidity (currency and gold) led the Politburo to consider exporting in order to make a profit on art and antiques. These sales were studied by Elena A. Osokina, “Gold for industrialization. The sale of artworks by the USSR in France during the period of Stalin’s five-year plans”, in Cahiers du Monde Russe, no. 41/1, January-March 2000. Auctions began in the early 1920s and increased after 1927 when a whole process of expropriation and confiscation of property was put in place. In 1927, the Sovnarkom proposed “to organize the export out of the USSR of antiques and luxury items, namely: antique furniture, household objects, devotional artifacts, bronze, porcelain, crystal, silver, brocade, rugs, tapestries, paintings, autographs, precious gems of Russian origin, handicrafts and other objects not of value to museums”. This last point was not retained and was especially adapted to enable the auction of “objects having a value for the museums”.

The Soviets thus orchestrated several auctions where the old paintings and the most beautiful pieces of French decorative arts were presented for public sale at the Rudolph Lepke Gallery in Berlin. The Stroganov Collection was sold on 12 and 13 May 1931 (see fig. 8 and 9).

Couverture du catalogue de la vente Stroganoff, 1931.

The large salon of the house was decorated with a Louis XVI fire screen. Made by Jean-Baptiste Sené and Alexandre Régnier under the direction of Jean Hauré (estimate: €70,000-€100,000), it was presented to King Louis XVI in 1787 at the Château de Saint-Cloud. After the upheavals of the Revolution, it was used by Napoleon I at the start of his reign, before joining the “Garde-Meuble”, where the official furniture was stored, in 1808.

Lot 12. A carved giltwood firescreen, Louis XVI, by Jean-Baptiste Sené, the sculpture by Alexandre Régnier, under the direction of Jean Hauré, delivered in 1787 for King Louis XVI at the Château de Saint-Cloud, regilt. Estimate 70,000 — 100,000 EUR. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the carved upper frame centred with the head of Athena wearing a helmet with an owl, flanked by rosettes and scrolls ending in lion masks, above egg and dart and fluting, the stiles with entwined berried laurel leaf fasces ending with rosettes and lion masks, on four scrolled acanthus leaf and lion paw feet, the lower frame centred by allegories of Trade and Prudence, caduceus and a mirror with a snake; with a double sided silk screen.

Provenance: - By Jean-Baptiste Sené and Alexandre Régnier under the direction of Jean Hauré for King Louis XVI's Bedroom at the Château de Saint-Cloud in 1787;

- Emperor Napoleon's Bedroom at the Palais des Tuileries in 1807;

- Transferred to the Garde-Meuble impérial in 1808.

Literature: - Saint-Sère, « Le Cabinet de l'amateur et la mode », in Plaisir de France, n°210, April 1956, p. 45 (ill.)

- P. Verlet, Le mobilier royal français, vol. I, Paris, 1990, n° 36, pp. 100-104, pl. L-LI (ill.)

- P. Verlet, Le mobilier royal français, vol. IV, Paris, 1990, n° 46, pp. 167-169 (ill.)

- Le Cabinet de l'Amateur, exh. cat. Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, 1956, n° 223, p. 65

RELATED LITERATURE

- B. Chevallier, Saint-Cloud, le palais retrouvé, Paris, 2013

- P. Verlet, Le mobilier royal français, Paris, 1945, n° 36, pp. 100-104 and pl. L-LI

Note: In his book on the history of French Royal furniture, Pierre Verlet devoted himself to studying, in great detail, the sumptuous furniture within the King's Chamber at the Château de Saint-Cloud which was built in 1787, with the carpentry by Jean-Baptiste Sené and the sculpture by Alexandre Régnier.

Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait de Louis XVI, roi de France, 1778, château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot

Etienne Allegrain, Vue cavalière du château de Saint-Cloud (détail), château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot

A few years after the publication of his book and probably due to loans for the “Le Cabinet de l’amateur” exhibition at the Orangerie in 1956, where the Comte de Ribes lent many works including the famous “Clock with Negress” and this fire screen, Pierre Verlet was able to add to his initial research and republished an in-depth study in 1990.

The 1789 inventory of the Château de Saint-Cloud details very precisely a piece of furniture (set of carpentry wares comprising matching furniture including: a bed, a pair of large armchairs, twelve folding chairs, a folding screen, our fire screen and a stepladder) describing martial iconography with warrior attributes and military trophies.

“The wood for the armchairs, folding chairs, folding screen and fire screen are all sculpted, namely: the wood on the armchair, with back legs in the form of fasces adorned with laurel leaf, spike and cannonball, the centre of the rail with a Minerva head and laurel leaf branches, rounded shield, the rest is composed of Ionic capitals, crowns, water-leaves, ropes, acanthus leaves, rosettes, volutes, grooves, lion heads, etc. ; wood on X-frame chair and cross beams with lion heads and egg and dart pattern, water-leaves, grooves, and beads, brackets, rood beams, crowns and lion paws, cross beams are adorned with a rounded shield, Apollo’s head, laurel leaf crown and branches in the centre; the wood on the folding screen, fire screen is analogous to the earlier noted wooden chairs.”

Jean-Baptiste Sené was in charge of furniture, as attested by his memoir:

“8bre (October) 87. The 4. N 2. Saint-Cloud. For the service of the King. (...)

- The carpentry of a bed with 2 bedside tables (...) 700 L.

- For the bed model (...) 48 L.

- For change (...) 54 L.

- A wood-veneered stepladder (...) 16 L.

- The carpentry of two large armchairs prepared in walnut wood (...) 48 L.

- The carpentry of twelve folding chairs (...) 252 L.

- A folding screen of 6 wood-veneered panels (...) 27 L.

- A screen with hats, made of walnut, prepared to be richly sculptured, the feet brackets assembled in two parts ......................... 30 L.”

Terracotta and wax scale models were needed prior to the final fabrication of the furniture, Martin had provided Sené a “model of armchair and screen in wax to instruct the execution ........ 72 L.”

Hauré, who supervised all the production entrusted most of the sculpture to Alexandre Régnier:

Memoire by Hauré. 1st semester 1788. Saint-Cloud. Month of 8th. 4. N 1st. for the King's Bedroom.

“For the sculpting of the King's bed (...)

- Alexandre (Reignier) - For sculpting the whole bed, paid ...... 1.356 L.

- Alexandre - For the sculpting of the two large armchairs analogue to the bed .... 336 L.

- Alexandre, eleven; Vallois, a - 12 X-shaped folding chairs, analogue to armchairs .... 1.152 L.

- Alexandre - A square screen analogue to the bed; on the top rail, Minerva head and branches of lilies, uprights in bundles, cross rails embellished with the attributes of Prudence and Wisdom, feet brackets with lion claws, very rich allover ...... 216 L.”

Chatard undertook the gilding: “the golden gilt burnished with great care” was estimated at the price of 4,860 livres.

The upholsterer Capin was in charge of the fabrics which were woven in Lyon.

“Order no. 2. From 4. 8bre (October) 1787. Capin will make for the Sleeping Chamber for the King a furniture with gros de Tours embroidered white ground, arabesque flowers pattern (...).”

Desfarges had the “white gros de Tours embroidered with arabesques for the summer” made for 56,538 livres, this expenditure concerned all furniture items, the curtains and doors. Silks were often the largest expense, while the lace maker, Fizelier's accessories were more costly than carpentry and sculpting combined, and as much as the gilding.

After the torment of the Revolution and its use by Napoleon I during his early reign, this suite of furniture was reinstated into the Garde-Meuble (Royal Household) in 1808. It was transferred to the Château de Fontainebleau in 1839 for the bedroom of the Duc d’Orléans, where it was completed. The bed underwent transformations by Michel-Victor Cruchet, a screen was renovated, four chairs and two other armchairs were made under Louis-Philippe to complete the set. Pierre Verlet praised the skill of the artisans who made the additions, the armchairs were made to the model and present minimal differences to the carved ornaments. On the other hand, due to the missing model, the screen has had a freer and less precise interpretation. The motif with the attributes of Prudence and Wisdom so delicately carved along the bottom of the framework of the original screen was replaced on the reworked screen, with the Apollo head cartouche which is on the headboards of the bed and the front crossbar of the armchairs. The bed, armchairs and four chairs are now kept in the bedroom of Pope Pius VII at the Château de Fontainebleau (Figs 4 and 5) while part of the panel of one screen is in the Louvre Museum.

J.-B. Sené et A. Régnier, Fauteuil d’un ensemble de sièges et lit pour la chambre de Louis XVI au château de Saint-Cloud, 1787.

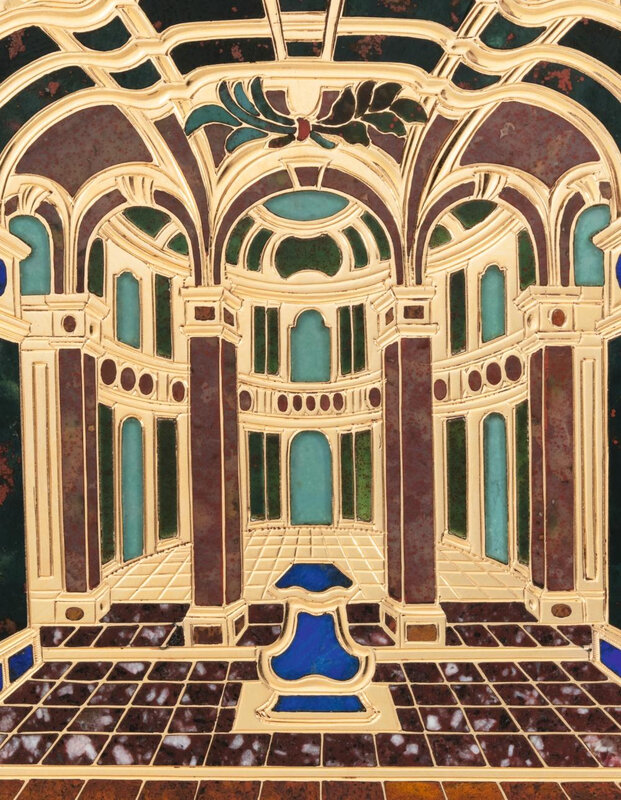

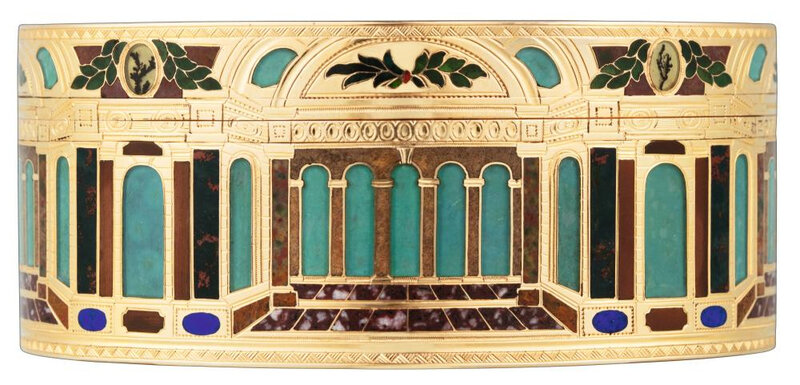

The collection is highlighted by a magnificent set of gold boxes, mainly dating from the second half of the 18th century. Among these treasures is a splendid oval snuffbox in gold set with hard stones, made in Dresden, circa 1770 (estimate: €500,000-€700,000), decorated with a perspective view of the interior of a temple. Further highlights showcase the great jewellery houses, with a cigarette case by Cartier in nephrite mounted in gold, circa 1910 (estimate: €12,000-18,000) and a gold Bulgari powder compact set with sapphires and diamonds, circa 1960 (estimate: €8,000-12,000).

Lot 59. A gold and pietra dura snuff box, Johann Christian Neuber, Dresden, circa 1770; 8.7 cm, 3 3/8 in wide. Estimate 500,000 — 700,000 EUR. Courtesy Sotheby's.

oval, the chased gold cagework inlaid on lid and base in a variety of hardstones including porphyry, bloodstone, agate, lapis and chalcedony with an architectural perspective of galeried arches framed by pillars set with oval moss agate panels and below loose laurel swags, the lid with a central lapis lazuli table, the sides with a similar arrangement of arches and pillars strikingly contrasting teal green chrysoprase arcades with bloodstone and orange agate pillarets below further laurel swags and moss agate ovals, the gold delicately engraved to emphasise the architectural elements and with narrow chevron borders to the sides, apparently unmarked, in plush-lined green shagreen case.

Provenance: - Collection of Alexander Baring, 4 th Baron Ashburton (1835-1889)

- Sold by his daughter, Mrs Adam, Christie's, 7 July 1947, lot 13