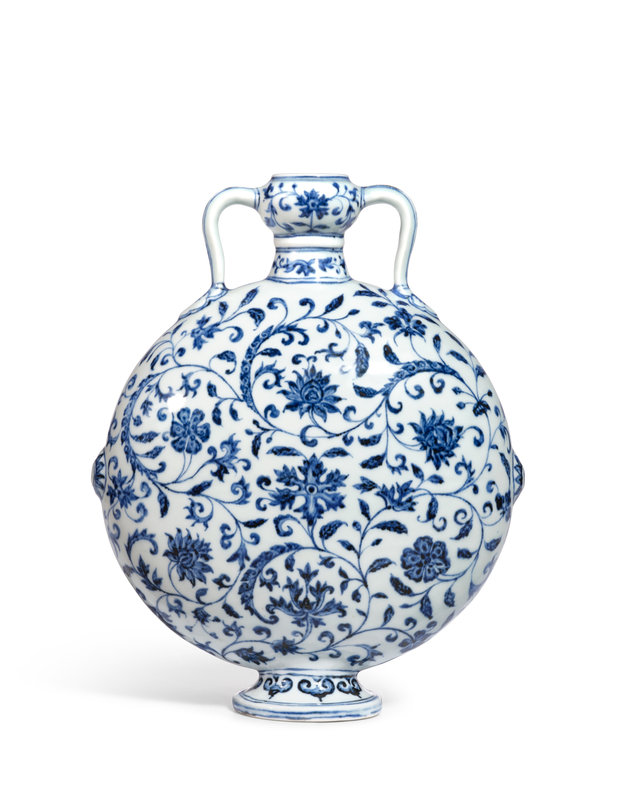

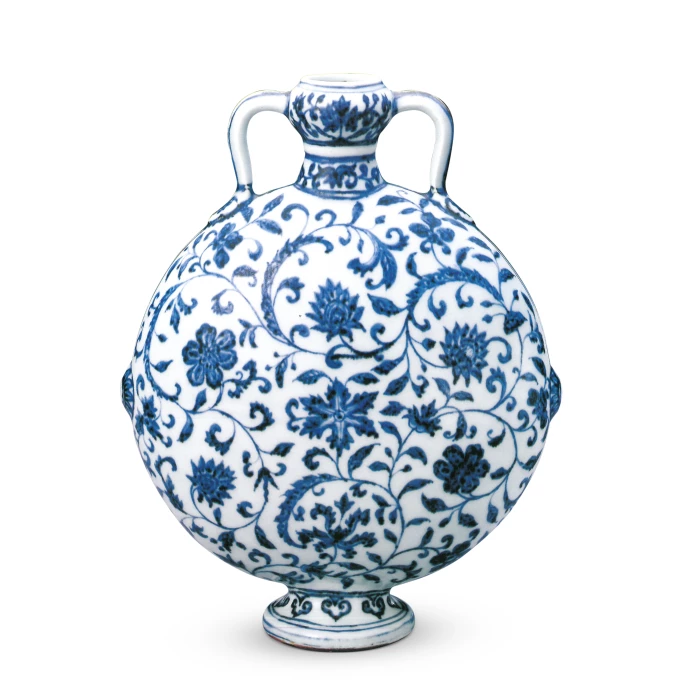

A superb and exceptionally rare blue and white 'floral' moon flask, Ming dynasty, Yongle period

A superb and exceptionally rare blue and white 'floral' moon flask, Ming dynasty, Yongle period (1403-1424); 28.6 cm. Lot Sold 85,618,000 HKD (Estimate Upon Request). © Sotheby's 2023

modelled after a Middle Eastern metal prototype, elegantly potted with a flattened moon-shaped body rising from a circular splayed foot to a garlic neck flanked by a pair of handles ending with ruyi-shaped terminals on the shoulders, further decorated with a domed lug detailed with a floral motif at the centre of each narrow side, the narrow sides painted with vertical lines interrupted by the handles and lugs, as though composed of two vertical halves, each side of the vase superbly painted in rich cobalt tones with a single flowering stem springing from the bottom of the vessel and scrolling in a full circle around the domed surface while rhythmically bearing seven stylised blooms, rich foliage, and unusual fronds, the neck collared by a band of stylised floral springs below floral sprays encircling the bulbous mouth, all beneath a most lustrous transparent glaze, the flat unglazed base centred with a well hollowed-out, glazed, globular recess.

Provenance: Discovered in West Yorkshire in March 1986.

Sotheby's London, 9th December 1986, lot 198.

Literature: Zhongguo ming tao Riben xunhui zhan. Gang Tai mingjia shoucang taoci jingpin [Exhibition of famous Chinese ceramics touring Japan. Fine ceramics from private Hong Kong and Taiwanese Collections], Museum of History, Taipei, 1992, p. 117.

Geng Baochang, Ming Qing ciqi jianding [Appraisal of Ming and Qing porcelain], Hong Kong, 1993, pl. 55.

Exhibited: Chinese Porcelain. The S.C. Ko Tianminlou Collection, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1987, cat. no. 12.

Selected Treasures of Chinese Art, Min Chiu Society Thirtieth Anniversary Exhibition, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1990-91, cat. no. 128.

Blue and White Porcelain from the Tianminlou Collection, Chang Foundation, Taipei, 1992, cat. no. 28.

Chūgoku meitō ten: Chūgoku tōji 2000-nen no seika [Exhibition of important Chinese ceramics: Essence of two thousand years of Chinese ceramics], Nihonbashi Takashimaya, Tokyo, and six other locations in Japan, 1992, cat. no. 73.

Blue and White Porcelain from the Collection of the Tianminou Foundation, Shanghai, 1996, cat. no. 29 and cover.

Metal, Wood, Water, Fire and Earth: Gems of Antiquities Collection in Hong Kong, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 2001-04, cat. no. 20.

In Pursuit of Antiquities: 40th Anniversary Exhibition of the Min Chiu Society, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 2001, cat. no. 150.

Art and Imitation in China, The Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong, University Museum and Art Gallery, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2006, cat. no. 175.

The Radiant Ming 1368-1644: Through the Min Chiu Society Collection, Hong Kong Museum of History, Hong Kong, 2015, cat. no. 64.

Treasures of Hong Kong: The 20th Anniversary of Hong Kong's Handover, Capital Museum, Beijing, 2017, cat. no. 117.

EXOTICISM FOR THE CHINESE COURT

Regina Krahl

This flask marks a poignant moment in the development of Chinese porcelain. The Yongle Emperor (r. 1403-24) had a far-sighted international outlook and rang in a cosmopolitan period. He initiated and encouraged contacts to many countries of Asia and as far west as East Africa, distributed some of China’s finest artefacts as diplomatic gifts and accepted in return whatever foreign goods might be offered. Diplomatic missions thus exchanged not only objects and materials, but also ideas and aesthetic concepts. This contact with and interest in other cultures left an indelible mark on China’s crafts, and ceramics as one of the most adaptable media handled by the imperial workshops were directly influenced.

In terms of its shape as well as its design, the present porcelain flask can be considered a result of this outward-looking policy of the Yongle Emperor. Made at the Jingdezhen imperial kilns, it represents the outstanding, high qualitative standard demanded at the time by the court: porcelain and glaze are extremely fine and even, the striking shape is well-proportioned and exactingly fired, the cobalt painting shows a strong blue, the brushwork is sophisticated, and the complex design harmoniously laid out.

Although both shape and decoration of this flask are clearly foreign-inspired, it is difficult to find convincingly close prototypes for either, since China’s craftsmen never copied but absorbed and revamped foreign styles. Pottery pilgrim flasks of basically similar form, mostly without a foot, suitable for carrying on long travels, can be traced in the Middle East to the second millennium BC, but the Yongle potters probably took their immediate inspiration from nearly contemporary Middle Eastern metal vessels.

With its moon-shaped body of oval section, locked between a circular neck and a circular foot, the present flask is most unusual in concept. The flattened shape runs counter to a Chinese potter’s typical working methods, where upright vessel forms were generally created by throwing on the wheel horizontal sections, which were then adapted, luted together and the joins so finely smoothed out on the outside that they were no longer apparent. On the present flask, where bottom and top half were also assembled horizontally, we are visually led to believe otherwise: painted vertical lines down the narrow sides, that seem to continue under the handles and lugs, create the impression of a flask composed of two vertical halves, front and back, joined together. The rudimentary domed lugs at the widest point may echo bosses on a metal example, or else are the potter’s answer to the more typical ring handles, which served for suspension on a chain or ribbon of the metal flasks, that mostly had no foot, but were unnecessary on a porcelain example with a foot. The foot itself received special treatment: turning the flask over reveals that what looks like a flared ring foot has in fact a smooth, flat unglazed base underneath, with a well hollowed-out, glazed, globular recess in the centre – a very neat detail.

The decoration of this flask is no less remarkable than its shape. A single flowering stem on each side that is bearing seven blooms, a large array of leaves, and unusual curving fronds, springs from the bottom and rhythmically scrolls in a full circle around each side, perfectly covering the available space. Although some flower-heads resemble lotus blooms, they are accompanied neither by naturalistic large dish-shaped lotus leaves, nor by the idealized pointed, jagged leaves that identifies the lotus as a Buddhist motif. Other flower-heads seen in full frontal view are more stylized and although different leaf forms occur on the scroll, they are not obviously associated with particular blooms, which therefore cannot be identified. The combination with those alien fronds makes the composition altogether fanciful. The fronds are made up of a series of individual hooked scroll elements, attached to only one side of the vein or stem, while the other side shows just the odd tendril or small leaf. Such one-sided leaf fronds or flower panicles do not seem to occur in nature.

Leaf-scroll motifs, often referred to as arabesques, are a quintessential Middle Eastern decorative feature that appears in endless variations is Islamic art and has been discussed by art historians since the nineteenth century. Related fronds have been called ‘Halbpalmetten’, or half palmettes (Alois Riegl, Stilfragen, Berlin, 1893, p. 264), and related leaf scrolls have been deemed ‘naturfern’, far from nature (Ernst Kühnel, Die Arabeske. Sinn und Wandlung eines Ornaments, Wiesbaden, 1949, p. 3). Seemingly one-sided fronds appear on Kashan tiles dated in accordance with 1262, collected at the British Museum, London (e.g. nos G.454, 455, 473, 475, 480, 482); and a somewhat reminiscent, free arrangement of flowers and fronds can also be seen on a Kashan tile of similar date, in Robert Hillenbrand et al., The Sarikhani Collection. An Introduction, London n.d. [2011], pp. 60-63; but Persian tiles are most unlikely to have served as models for Chinese craftsmen. On portable art works such as the illuminations and bindings of books, or textiles, related motifs are usually found in much more formal, strictly symmetric layouts.

Imaginative designs vaguely inspired but not representing nature are characteristic of Islamic art, where naturalistic representations were spurned. It is one of the fundamental differences between Middle Eastern and Chinese design, where a connection with nature was always important and is apparent even in freely interpreted, stylized flower motifs. It is most interesting to compare a flask of the Yongzheng period (1723-35), for which a piece like the present one must have served as inspiration; making only slight changes, the porcelain painters translated the design into a purely Chinese motif, depicting lotus blooms with lotus pods, lotus leaves and arrow-head plants, and turning the fronds into wispy fern-like water weeds (see Geng Baochang, ed., Gugong Bowuyuan cang wenwu zhenpin quanji. Qinghua youlihong/The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum. Blue and White Porcelain with Underglazed Red, Shanghai, 2000, vol. 3, pl. 98) (fig. 1).

fig. 1. A blue and white 'floral' moon flask, Qing dynasty, Yongzheng period, Qing court collection © Palace Museum, Beijing.

Blue-and-white pilgrim flasks can be seen in use in Persia in several Islamic miniatures; a flask with a floral design appears, for example, in a depiction of a festivity in a Safavid palace garden, from an album produced for Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524-76) between 1539 and 1543 (see Sheila R. Canby, The Golden Age of Persian Art. 1501-1722, London, 1999, pl. 36) (fig. 2), but no flasks of this form are included either among the pieces from the Savavid royal collection handed down at the Ardabil Shrine, Iran, or the Ottoman royal collection preserved at Topkapi Saray, Istanbul, Turkey. These porcelains in foreign styles were not necessarily meant for export; they seem to have been equally popular at the Chinese court, where their exotic aspect might have been deemed particularly appealing.

fig. 2. 'Khusrau listening to Barbad playing the lute' from Khamsa by Nizami, 1539-1543, and detail © The British Library Board Or. 2265 f.77v.

The Palace Museum, Beijing, holds the only known companion piece to the present flask, as well as another flask of the same shape with a different design, and several other Yongle blue-and-white vessels of Middle Eastern metal shapes painted with basically the same foreign flower scroll, almost all handed down from the Qing court collection. The companion piece is illustrated in Geng Baochang, op.cit., 2000, vol. 1, pl. 38; and in Geng Baochang, ed., Gugong Bowuyuan cang Ming chu qinghua ci [Early Ming blue-and-white porcelain in the Palace Museum], Beijing, 2002, vol. 1, pl. 35 (fig. 3). Four large canteens with flat unglazed back, a jug and a deep globular bowl in the Gugong, all similarly decorated, are published in Geng Baochang, op.cit., 2000, vol. 1, pls 34-37, 42, 52, as well as a similar flask with a geometric design, pl. 39. A large canteen with the same flower scroll as seen here is also in the Taipei Palace Museum, see the exhibition catalogue Shi yu xin: Mingdai Yongle huangdi de ciqi/Pleasingly Pure and Lustrous: Porcelains from the Yongle Reign (1403-1424) of the Ming Dynasty, Palace Museum, Taipei, 2017, pp. 122-5.

fig. 3. A blue and white 'floral' moon flask, Ming dynasty, Yongle period, Qing court collection © Palace Museum, Beijing

John Pope has interpreted the frond design on another such vessel in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. as “vines of closely bunched rows of little leaves, buds or seed pods on only one side of the vine that look not unlike some sort of parasitic growths or even, by not too great a stretch of the imagination, like furry caterpillars” (John Pope, “An Early Porcelain in Muslim Style”, in Richard Ettinghausen, ed., Aus der Welt der Islamischen Kunst. Festschrift für Ernst Kühnel, Berlin, 1959, p. 364). The Freer Gallery also holds an albarello (jar shaped like a Western apothecary jar) with similar decoration, illustrated ibid., pl. 6 A.

Flasks of the present form with geometric design are less rare and known from several examples. That design can more directly be traced to Islamic models, for example an illustration in a Quran of 1313, see the flask sold in these rooms, 6th April 2016, lot 17, from the Pilkington collection (fig. 4), where the comparison is illustrated in the catalogue p. 85. This form of flask is also known with another imaginary flower design, as sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 27th November 2007, lot 1664.

fig. 4. A blue and white moon flask, Ming dynasty, Yongle period, from the Pilkington collection, Sotheby's Hong Kong, 06 avr. 2016, lot 17.

Sotheby's. A Magnificent Yongle Blue and White Moon Flask, Hong Kong, 9 October 2023

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240512%2Fob_1b86bd_telechargement-12.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240512%2Fob_2e1ec7_telechargement-7.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240510%2Fob_25eb10_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_2a8420_437713933-1652609748842371-16764302136.jpg)