"Giacometti" @ the Kunsthaus Zürich

Alberto Giacometti, Self-portrait, 1921, Oil on canvas, 82,5 x 72 cm, Kunsthaus

ZURICH.- From 27 February to 24 May 2009, the Kunsthaus Zürich exhibits masterpieces from the Egyptian Museum in Berlin – including busts of Akhenaton and Nefertiti, the block statue of Senemut, and the so-called Berlin Green Head – together with sculptures, paintings and drawings by Alberto Giacometti, who was profoundly influenced by ancient Egyptian art.

The exhibition constitutes the first attempt to visualize the analogies between the work of Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), the leading Swiss artist of the 20th century, and the visual culture of the ancient Egyptians, as represented by valuable works on loan to the Kunsthaus Zürich from the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. Visitors will be surprised by Giacometti’s deployment of the Egyptian ‘style’, including its concentration on the human form, its relation of figure to space, and its basic artistic intention, which was to secure for the individual an eternal present.

ASSIMILATION BY COPYING

Giacometti was still a student when archaeologists from Berlin excavated the treasures of Akhenaton in Amarna in the early 20th century, but the young artist was immediately convinced of the Egyptian culture’s superiority to all of its subsequent counterparts. Giacometti first encountered original Egyptian artifacts in 1920 in Florence, where he was confronted with the reification of his own artistic aspirations: a distillation of reality, the living presence of humanity in a stylistic form. It was the beginning of a life-long relationship. Upon his return from Italy, Alberto presented his father and mentor Giovanni with an earnest of his maturity as an artist in the form of a masterly full-figure selfportrait. The painting, in which Giacometti styles his own features after the gaunt, elongated face of Akhenaton as a token of his respect for the ancient genre, is featured in the exhibition alongside a bust of the pharaoh himself.

In Paris, as a disciple of Bourdelle’s, Giacometti tried his hand at portraying living models. He studied Egyptian artifacts at the Louvre and copied illustrations from books. Egyptian philosophy played a role in the thinking of the Surrealists, who counted Giacometti as a fellow traveller at the time, and, when his father Giovanni died in 1933, Alberto began to focus on ideas of death and the beyond. Giacometti’s ‘Cube’ with an engraving of a self-portrait can be seen as the modern artist’s response to the Egyptian block statues that had so fascinated him in Florence, the most influential of which, depicting the ancient architect Senemut, will also be on show at the Kunsthaus.

Giacometti began his most intensive encounter with ancient Egyptian art in 1934, when he drew himself as a ‘writer’. What may be termed Giacometti’s‘phenomenological realism’, his attempt to record reality as it arises in the process of seeing, developed in the dialogue between his drawn self-portraits and his pellucid copies of Egyptian masterpieces, such as the so-called Berlin Green Head, also on display in Zurich.

LINEAMENTS OF A MATURE STYLE

In and around 1942, Giacometti drew numerous versions of the fresco of the garden of Ipy, copying it more than any other work of art. His landscapes which are obviously indebted to that work indicate his fascination by the rhythmic lines of its trees and shrubbery, and by the vibrant web of taut linear structures in which it catches life on the fly, as well as the powerful forces of nature.

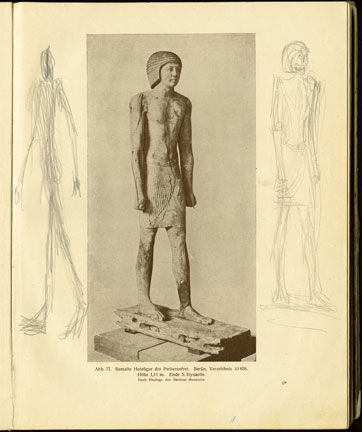

It had begun to dawn on Giacometti that the essence of life is motion, which Egyptian art emblematizes in the paradigmatic form of the striding figure. This ancient typology, which was to provide Giacometti with a template for his own striding men, grants the nervous subjectivity of modern perception a basic solidity. The latent movement depicted is made manifest in a given figure’s pedestal as well as in the tension between the figure and its spatial environment created by its oversized feet. While the Egyptian sculpture’s lifelike quality was a function of the Ka, or soul, immanent within it, Giacometti accomplishes the same effect in his work by way of the restlessness in the eye of its beholder, initially the artist himself, and subsequently his viewers.

The Egyptian typology was to become a central benchmark for Giacometti’s postwar production. In the busts he created in the 1950s and 1960s, Giacometti dramatically increased the contrast between the chaos of his subjects’ nether parts and the life reflected in their gaze. The highest degree of this contrast, in ‘Diego assis’ and ‘Lotar III’, was achieved in reference to ancient Egypt’s kneeling figures. These works testify to something many witnesses of Alberto’s working methods have also noticed: his continual renewal of the creative process, the guarantor of vitality which was perfected in the viewer’s parallel act of perception. One is reminded of the Egyptian notion that the sun god ensures the continuation of life by restaging the genesis of the cosmos anew every morning as he rises from the primeval waters.

THE PRESENTATION IN BERLIN AND ZURICH

The ancient Egyptian artifacts can be seen until 15 February 2009 in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, together with 12 sculptures by Giacometti. The Kunsthaus show will then feature 18 Egyptian sculptures in judicious juxtaposition with comparable works of Alberto Giacometti and as many as 80 other pieces by the Swiss artist, including paintings, a significant number of masterful drawings after Egyptian models, and the two books in which Giacometti drew more marginalia than in any other, Fechheimer’s ‘Die Plastik der Ägypter’ and Ludwig Curtius’ Egypt volume in the handbook of art history. The exhibition was curated by Christian Klemm, conservator of the Alberto Giacometti Foundation and of the collection at the Kunsthaus Zürich. The subject of the show is considered in greater depth in a publication featuring essays by Klemm and the curator in Berlin, Dietrich Wildung, available for sale at the Museum Shop and in bookstores.

Alberto Giacometti, Echnaton, um 1921 Bleistift, 29,9 x 38,4 cm, Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris © 2009 ProLitteris, Zürich

Drawings by Alberto Giacometti in Ludwig Curtius’s «Ägypten und Vorderasien», Berlin 1923

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F60%2F34%2F119589%2F128961949_o.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F48%2F57%2F119589%2F127874617_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F66%2F66%2F119589%2F127181870_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F46%2F13%2F119589%2F126868716_o.jpg)