Qianlong – Scholar and Calligrapher sold at Sotheby's Hong Kong, 3 october 2018

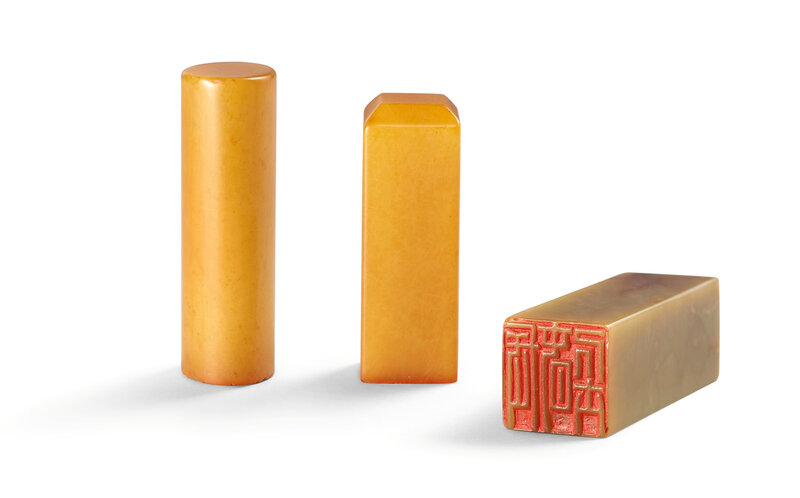

Lot 3205. An outstanding set of three Qianlong princely soapstone seals with a fitted zitan box ; the seals: Qing dynasty, Yongzheng period ; the box: Qing dynasty, Qianlong period. Estimate: 40,000,000-60,000,000 HKD. Sold Price: 46,352,000 HKD (5,912,661 USD). Courtesy Sotheby's.

the first a square seal of a dark grey soapstone, the seal face carved with a four-character inscription reading Changchun Jushi ('The scholar of everlasting Spring'), the second of oval form of a tianhuang stone, carved with a three-character inscription reading Suianshi ('Studio for following peace'), the third a rectangular seal of a rich tianhuang stone, carved with the characters Bao Qinwang bao ('Treasure of Prince Bao of the First Degree'), the fitted zitan box with three red silk-lined cavities and a repeated motif diaper-ground brocade, the top of the gold-flecked zitan cover gilt-inscribed with the three seal inscriptions in regular script, the interior with matching red silk lining.

middle 6.2 by 2.9 by 1.9 cm, 2 3/8 by 1 1/8 by 3/4 in.; 71.1 gr.

right 5.7 by 2.2 by 2 cm, 2 1/4 by 7/8 by 3/4 in.; 65.3 gr.

box 8.7 by 10.2 by 5.6 cm, 3 3/8 by 4 by 2 1/4 in.

Christie’s Hong Kong, 3rd November 1998, Lot 1077.

Sotheby's Hong Kong, 26th October 2003, lot 26.

Bao Qinwang bao zuxi

A Group of Treasures of

The Prince of the First Degree

Guo Fuxiang

These three seals are made from material equal to the best quality brilliant and translucent dong stones. Their inscriptions include one with raised characters reading Suianshi, another with recessed characters reading Bao Qinwang bao and another one with raised characters reading Changchun Jushi.

This group of seals was used and produced before the Qianlong Emperor ascended the throne, while he was still Crown Prince (fig. 1). In the Record of Qianlong Imperial Seals, Qianlong baosou, which is kept in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, it is recorded that “before he ascended the throne, seventy seals were ordered to be made, and they were divided and kept in thirteen special boxes. After each was carefully recorded and the various seals used, the phrases on the seals were recorded on a list which together formed a meaning.” From this passage, we know that Qianlong as a Prince had seventy seals made for himself and they were divided and fitted into thirteen seal boxes, of which the present set of seals is one. The box is made from zitan, carved with the seal inscriptions in regular script on the outside, and the interior of the box, into which the seals are fitted, is lined with brocade. The workmanship is of the highest calibre and its abundance of luxury testifies to the dignified air of the imperial family.

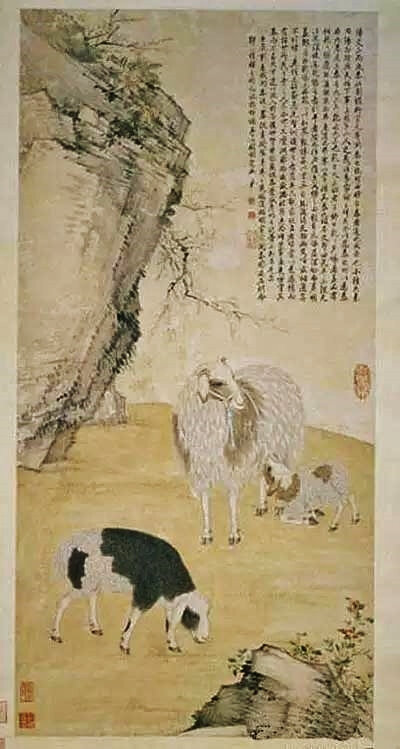

fig. 1. Giuseppe Castiglione, Picking Spirit Fungus, Qing dynasty, Yongzheng period, scroll, ink on paper. Image Courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing.

In the Qianlong Emperor’s imperial essay Jia yan ji it is stated “In the winter of the 46th year of the Qianlong period, I respectfully gathered all the imperial seals used by my grandfather and generations of ancestors as well as those used in the ten or so years between taking residence in the Green Palace (residence of the Heir Apparent) and the ascendency to imperial power, had boxes made for them and had them stored in the Shouhuangdian.” From this we know that these thirteen boxes of seals from the time when the Qianlong Emperor was Crown Prince were originally kept in the Shouhuang Hall of Jingshan (an ancestral hall behind Coal Hill), and that they were properly registered to be cherished in the future and protected for generations according to the regulations. Unfortunately, China has experienced numerous misfortunes in its modern history, and the life of Imperial treasures inside the palaces was also susceptible to these unpredictable disasters. Of the thirteen sets of the Qianlong Emperor’s princely seals, aside from one box of sixteen seals in the collection of the Beijing Palace Museum (fig. 3), most others appear to have been lost through time. Thus this set of Bao Qinwang bao seals that is offered in this sale is the only set of the Qianlong Emperor’s Princely seals known to be in a private collection. Furthermore, the fact that a set that has been privately owned for a long period of time, resurfaces, is in itself a fortunate occurrence.

fig. 3. A set of sixteen Qianlong princely seals, Qing dynasty, Yongzheng period. Image Courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing.

It was in the 11th year of the Yongzheng reign that the Qianlong Emperor was conferred as the Heshi Bao Qinwang (Prince of the Blood of the First Degree, Bao) and was given the designation Changchun Jushi (Scholar of Everlasting Spring, fig. 2). The Shiqu baoji records that this group of seals was already used during the 12th year of the Yongzheng reign, thus we can conclude that these seals must have been made no later than the 11th year of the Yongzheng reign (1732), making them some of the earliest works of art made to the order of the Qianlong Emperor. What is also worth mentioning, is that the Qianlong Emperor often used seals in groups, and more often in groups of three which were kept in a box together. These sets of seals often comprised one of rectangular or oval section, which was inscribed with the name of a palace hall, and two of square section inscribed with a by-name or a phrase taken from a poem (see for example, fig. 4). The Bao Qinwang bao seals offered in this set are in fact the original set of this type. The concept of grouping seals into sets of three is out of convenience, and these seals have been impressed on a great number of works of art and are perhaps the most often used seals of the Qianlong Emperor’s early life (fig. 5).

fig. 2. Giuseppe Castiglione, Picking Spirit Fungus, Qing dynasty, Yongzheng period, scroll, ink on paper, detail. Image Courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing.

fig. 4. A set of three green jade seals, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period. © Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

fig. 5. Wang Zhenpang, Colophon from Pavilion of Five Clouds, Yuan dynasty, scroll. © Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Another strength of these seals is the value of the materials from which they were made, including top quality tianhuang and steatite stones; pure and smooth, brilliant and transparent, because they are not engraved and free of decoration, the brilliant colours of the stones really shine through. Although they are a little different in shape from the set of three Qianlong seals Puyi took with him in his flight from the Imperial Palace (fig. 6), they were likewise carved in a standard rectangular or oval form which wasted a lot of the stone in the carving process, thus displaying the extravagance of the imperial family.

fig. 6. A set of three imperial tianhuang seals, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period. Image Courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

Made from the best stones, with masterful craftsmanship, this can be considered a representative work of art from the Qianlong Emperor’s princely period.

A. Bao Qingwang bao

This seal is carved from a Shoushan (Fujian province) tianhuang dong (literally: ‘cold’) stone, its apex is multi-facetted and its body glossy and plain.

In the first month of the 11th year of the Yongzheng reign, he announced that his fourth son was to become Crown Prince. From then on, Qianlong began to participate in political affairs. This seal was made in that same year and was thus used mainly in the period between his appointment as Crown Prince and when he ascended the throne a year later (figs 2 and 5).

B. Suianshi

This seal is carved from a Shoushan (Fujian province) tianhuang dong stone, of oval section, it has a flattened apex which is left undecorated.

Suianshi is the name of one of Qianlong’s studies. The earliest Suianshi studio dates back to the time when Qianlong was still a prince and was the studio in which he would spend time studying and was a place where he could find peace and solitude. What is more significant is that Qianlong so liked this name, that he created Suianshi studios in the Five Gardens on the Three Mountains (the three mountains around Beijing, Xiangshan, Yuquanshan and Wanshoushan) as well as in various travelling palaces, for example, in the Western Garden, the Yuanmingyuan, and the Qingyiyuan (all in Beijing). In this way, and using Qianlong’s own nostalgic words, he could be constantly reminded of his youthful life and never forget the past. Since the present seal was made during the time he was Crown Prince, it was the first such seal, made for use in the original Suianshi studio. This seal, together with Bao Qinwang bao and Changchun Jushi seals were very often used on works of art during the time he was Prince (fig. 5).

C. Changchun Jushi

This seal is carved from Changhua (Zhejiang province) steatite dong stone. Its apex is multi-facetted and its body glossy and plain.

Changchun Jushi was the designation the Yongzheng Emperor gave to Qianlong while he was still a Prince. The Yongzheng Emperor was highly influenced by Buddhist teachings and in the 11th year of his reign he assembled fourteen ‘disciples’, of which Qianlong was one, into a meeting and personally preached the law to them; it was then that he first called Qianlong Changchun Jushi. It was in that year that this seal was made. Qianlong attached great importance to the designation Changchun and the numerous Changchun shuwu (libraries) all obtained their names from this by-name. This seal and the Bao Qingwang bao seal were both very often used by Qianlong before he ascended the throne (figs 2 and 5).

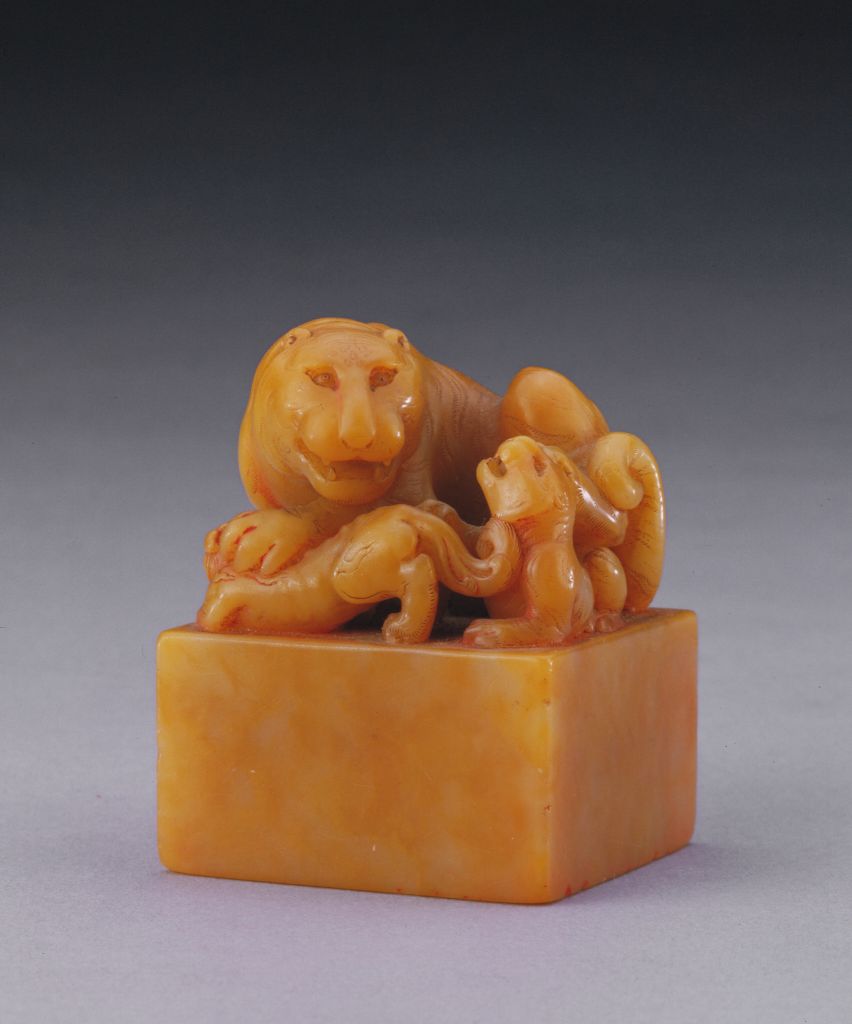

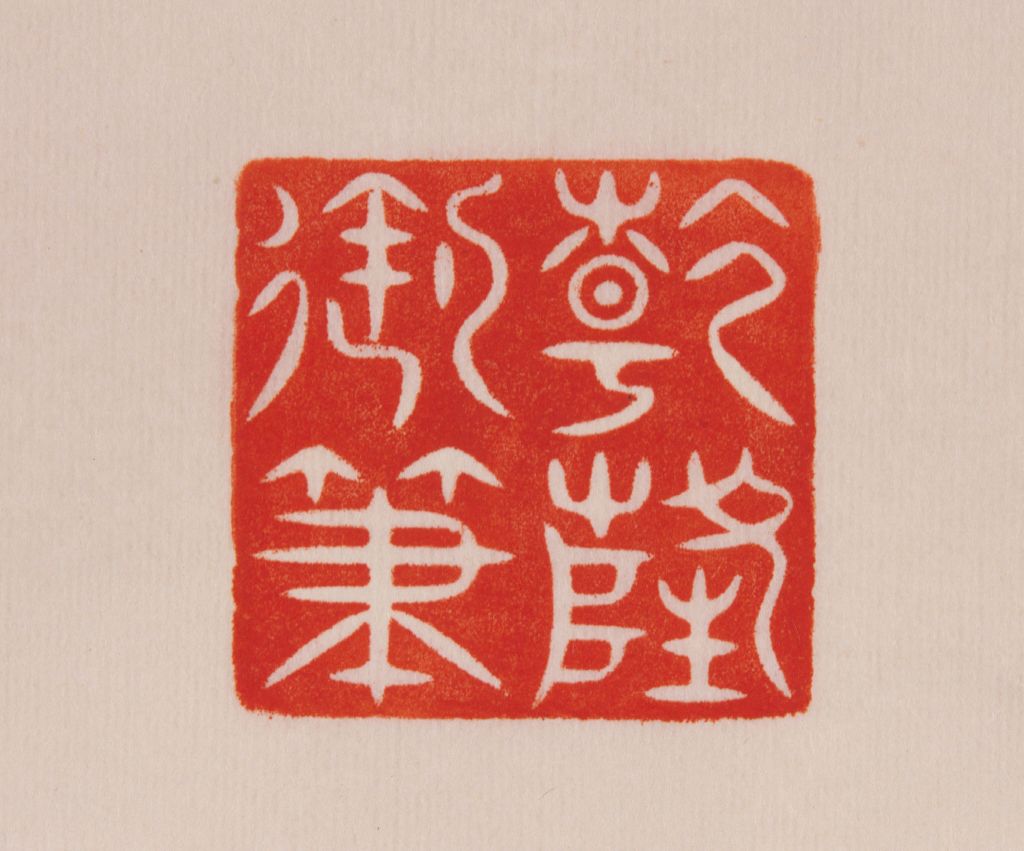

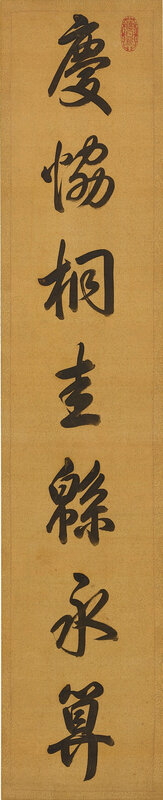

Lot 3201. A superb and exceptional imperial tianhuang 'chilong' seal and a pair of calligraphic hanging scrolls, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period (1736-1795); seal h. 7 cm, 2 3/4 in.; 212 gr.; each scroll 137.2 by 28 cm, 54 by 11 in. Estimate: 25,000,000-30,000,000 HKD. Lot sold 30,120,000 HKD (3,842,107 USD). Courtesy Sotheby's.

the seal powerfully carved in high relief with a mother chilong playfully nipping at the haunches of her two wrestling cubs atop an oval seal, each horned mythical beast meticulously rendered with a finely incised mane above piercing eyes and a pronounced snout, the seal face carved with a three-character inscription reading de re xin ('Virtue renewed every day') framed by a pair of sinuous chilong, the lustrous stone of a rich caramel colour with grey inclusions skilfully utilised to portray the darker fur and mane of the mother chilong; each of the pair of imperial hanging scrolls with semi-cursive calligraphy in ink on gold-flecked silk, mounted on green diaper brocade, one impressed with the de ri xin seal, the other with two further Qianlong seals and a collector's seal.

Provenance: Sotheby's Hong Kong, 26th October 2003, lot 28.

De ri xin

Virtue Renewed Every Day

Guo Fuxiang

This imperial jewel is carved from a tianhuang dong stone from Shoushan in Fujian province, and is carved in an ovoid form with three chilong. lts seal inscription is composed of the three-character phrase de ri xin ('Virtue renewed every day'). The phrase de ri xin is derived from Shangshu [The Book of History] where it is written: 'De ri xin, wan bang wei hai. Zhi zi man, jiu zhi nai li.' The meaning of this is that a gentleman should diligently build his moral character, and should daily progress and improve anew. The three characters carved on the Qianlong Emperor's seal thus sum up this phrase. What is even more meaningful is that the Qianlong Emperor used this three-character phrase as a name for one of his private studies. In fact, these words were personally inscribed onto a plaque and hung on the walls of the Jingshengzhai (Studio of Esteemed Excellence) within the Jianfugong (Palace of Established Happiness). But in 1923 (13th year of the Republic), when the Jianfugong was set aflame, the Jingshengzhai perished in the fires and the 'de ri xin' plaque along with it. Thus the fact that this treasure has survived through these perils is very remarkable.

According to the Shiqu baoji [The Precious Collection of the Stone Canal Pavilion], a written record of the paintings and calligraphies of the Qing court, the earliest record of this seal on a work of art dates back to the 8th year of the Qianlong reign (in accordance with 1743) thus dating the seal to before 1743 and within the early Qianlong period. This seal was often used together with the Qianlong Emperor's suo bao wei xian ('the only treasure is virtue') and Qianlong yubi ('Qianlong's imperial brush', fig. 1) seals and most often chopped on to his own imperial calligraphy and paintings and used as the leading seal (at the opening of colophons, fig. 2).

fig. 1. Tianhuang ‘lion and cub’ ‘Qianlong yubi’ seal and impression, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period © Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing

fig. 2. Explaining “An Auspicious Start” with an Imitation of Xuanzong’s “An Auspicious Start”, scroll, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period (1772). © Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

The stone from which this seal was carved has an excellent texture and its temperature and moisture are very agreeable. The colour of the body has a lustre and shine in its bright yellow, and the top section contains a chilong of a slight tinge of white, which is why we know that this stone is in fact cut from a precious Shoushan Mountain yin guo jin (literally 'gold wrapped in silver') tianhuang stone. This type of soapstone "is rarely seen and an outstanding type of tianhuang stone, which should be considered the most rare and precious of stones as it is the optimum combination of tianhuang and baitianstones," according to Ye Weifu, Zhongguo yin shi [Chinese stone seals]. Moreover, this seal is very large, and is amongst the largest tianhuang seals from the Qianlong period.

The three chilong that are carved atop this imperial seal seem to move naturally, the carved lines of their form are flowing and smooth. Their dense fur and manes flutter with ease without becoming disordered, and their bones and musculature are carved realistically and in great detail. The three animals turn around and playfully clamber to get close to one another, looking around, their faces display their enjoyment. All these characteristics are features associated with typical workmanship of Shoushan craftsmen during the Qianlong period.

Lot 3202. A superb imperially inscribed white Khotan jade bowl, Mark and period of Qianlong, dated yiyou year (in accordance with 1765); 12.7 cm, 5 in. Estimate: 4,000,000-6,000,000 HKD. Lot sold 4,920,000 HKD (627,595 USD). Courtesy Sotheby's.

exceptionally worked with deep rounded sides rising from a straight foot to an everted rim, the exterior inscribed with an imperial poem titled Yong Hetian yu wan ('In Praise of a Khotan Jade Bowl') extolling the flawlessness and rarity of the bowl, dated to the yiyou year of the Qianlong reign (in accordance with 1765) and followed by two seal marks reading bide ('compare yourself to jade') and langrun ('bright and lustrous'), the base incised with a four-character reign mark, the softly polished translucent stone of a lustrous even white colour.

Provenance: Collection of Elizabeth Parke Firestone (1897-1990).

Christie's New York, 22nd March 1991, lot 532.

Sotheby's Hong Kong, 26th October 2003, lot 33.

n Appreciation of the Qianlong Emperor’s Khotan White Jade Bowl

Xu Lin

From Khotan, the packaged tributes arrive every year,

Of rare beauty, like fat, suitable for making bowls.

The finished vessel illuminates the palace

and realizes the grand ceremonies;

I brush these poetic lines to praise its preciousness.

Without flaw or defect, the jade needs no concealment;

With sufficient capacity, the bowl contains plenty.

Over the generations my sons and grandson

will always cherish it:

A treasure on par with the ancient swords and bi discs.

In 1765, the Qianlong Emperor wrote the above poem, entitled ”In Praise of the Khotan Jade Bowls,” on a pair of Khotan white jade bowls. He begins the poem by referring to his own edict demanding tributary raw jade from Khotan every spring and fall, which greatly pleased him. Thanks to the consistent supply of raw jade, the court had sufficient access to the mutton-fat jade suitable for making bowls. For what purposes were such flawless jade bowls used? The Qianlong Emperor explains in his annotation to the poem that the bowls were used to serve milk tea bestowed during the celebratory ceremonies in his court. Such an important occasion warranted the Emperor’s poem and its inscription on the bowls. The Qianlong Emperor even believed that the bowls were as precious as jade blades and large bi discs of the ancient past, worthy as bequests to his descendants (fig. 1).1

![Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi san ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 3], juan 52, p. 2](https://i.pinimg.com/564x/33/9b/2c/339b2c8be007ad15daa08eddeeb73e19.jpg)

fig. 1. Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi san ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 3], juan 52, p. 2.

What are the current locations of these bowls used for the Qianlong Emperor’s ceremonial tea bestowal? According to my research, there are three such jade bowls. One is at the Palace Museum in Beijing, and another at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. The third is the Khotan jade bowl with the Qianlong Emperor’s imperial inscription presently on offer at Sotheby’s.

This jade bowl measures 5.6 cm in overall height. The flaring mouth measures 12.8 cm in diameter, and the ring foot measures 5.8 cm in diameter and 1 cm in height. The bowl was carved from Khotan white jade with a fine texture and lustre. It is undecorated except for the inscription of the Qianlong Emperor’s poem, which runs around the outer surface in alternating lines of four and three characters to create a rhythmic composition. Following the poem is an inscription and a date reading Qianlong yiyou jixiayue shanghuan yuti (‘Imperially inscribed during the first third of the month jixia of the year yiyou of the Qianlong reign’), a relief square seal in seal script reading bide (‘Compare yourself to jade’, and an intaglio square seal in seal script reading langrun (‘Bright and lustrous’). The year yiyou was the 30th year of the Qianlong reign, and the month jixia was the 6th lunar month. Shanghuan refers to the first third of the month, as evidenced by the Ming-dynasty writer Yang Shen’s Danqian zonglu. Qianlong-period objects inscribed with the Emperor’s poetry and prose are often also carved with dates, signatures, and informal seals.2 The base of the jade bowl is incised in seal script with the characters Qianlong nianzhi (‘Made during the Qianlong reign’). Done with an awl, the incision is deep and powerful.

This jade bowl was in the collection of Elizabeth Parke Firestone (1897-1990), whose son-in-law William Clay Ford was a grandson of Henry Ford, founder of Ford Motor Company. Firestone was fond of fashion and organised fashion shows. She also had a love of Chinese jades. After her passing, this jade bowl was auctioned at Christie’s New York in March 1991. In October 2003, Sotheby’s Hong Kong again auctioned it.

Two other jade bowls, bearing the same inscription, are in the Palace Museums of Beijing and Taipei respectively. The Taipei example is of the same type. I have not examined it in person, but according to published images and the introduction by museum expert Deng Shuping, it is similar in form and material to the bowl on offer. Both are undecorated except for the inscription of Qianlong’s poem, and both have the same signature and date, seals and reign mark (fig. 2).3

fig. 2. Inscribed white jade bowl, mark and period of Qianlong © Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

The Beijing jade bowl is made from white jade and has a high foot (figs 3 and 4).4 Its inscriptions and date are identical in textual content and script to those on the present bowl, but were carved more deeply. They are followed by two intaglio seals reading Dejiaqu and Jixia yiqing, which like Bide and Langrun were casual seals often used by Qianlong in conjunction with inscriptions of his poetry and prose on court jades. Compared to the lot on offer, the Beijing bowl has thicker walls, a shallower body, and a taller and thicker foot. Measuring 13.8 cm in diameter in the mouth, it is 5.7 cm in overall height, with a base of 6.7 cm in height, and is slightly larger than the lot on offer. Along the rim of its mouth and along the bottom edge of its body respectively, there are two bands of incised animal-face huiwen patterns. Notably, its base is carved in relief with the four characters Qianlong yuyong (‘For Qianlong’s Imperial use’) in seal script. The Beijing bowl’s form suggests that it was not created by the palace workshops or their subsidiaries in Suzhou and Yangzhou during Qianlong’s reign. Rather, it is an example of a Central Asian type.

fig. 3. Inscribed white jade bowl, yuyong mark and period of Qianlong Qing court collection. Image Courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

fig. 4. Carved mark on an inscribed white jade bowl (fig.3), yuyong mark and period of Qianlong Qing court collection. Image Courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing.

To understand why the Qianlong Emperor loved jade bowls, it is important to investigate this high-footed and thick-walled jade bowl. Jade bowls of the same type were sent to his court from Xinjiang in 1740, 1756, and 1758, during which time the Qing empire continually battled the Uyghur and Altishahr forces entrenched in Central Asia and expanded its control of the west. The 1740 and 1756 tributes are now in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, and the 1758 tribute is in the Palace Museum in Beijing. The 1740 bowl bears no inscription of imperial poetry, but the corresponding case made by the court includes a label specifying that it was sent by Galden Tseren, ruler of the Dzungars. The 1756 bowl bears an inscription of the Qianlong Emperor’s poem (fig. 5).5

![Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi er ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 2], juan 65, p. 18](https://i.pinimg.com/564x/a3/ce/bf/a3cebfa24d2a98be2afaff1f6a4bab76.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

![Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi si ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 4], juan 31, p. 18](https://i.pinimg.com/564x/35/6a/6b/356a6bc25cbbd3ad5237e8341ca34c57.jpg)

![Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi wu ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 5], juan 23, p. 8](https://i.pinimg.com/564x/32/96/a0/3296a081cdac364825f960d116ab7fd5.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F98%2F98%2F119589%2F129097971_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F93%2F75%2F119589%2F128489120_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F09%2F29%2F119589%2F128488304_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F62%2F18%2F119589%2F128488091_o.jpg)