Sotheby’s Hong Kong Presents the Most Significant Chinese Works of Art Sale Series to Take Place in the Last Decade

(Left to Right). The Private Collection of Joseph Lau. A Fine Blue and White 'Lotus Scroll' Vase, Meiping, Ming Dynasty, Yongle Period. Est: HK$ 25 – 35 million / US$ 3.2 – 4.5 million. © Sotheby's 2022

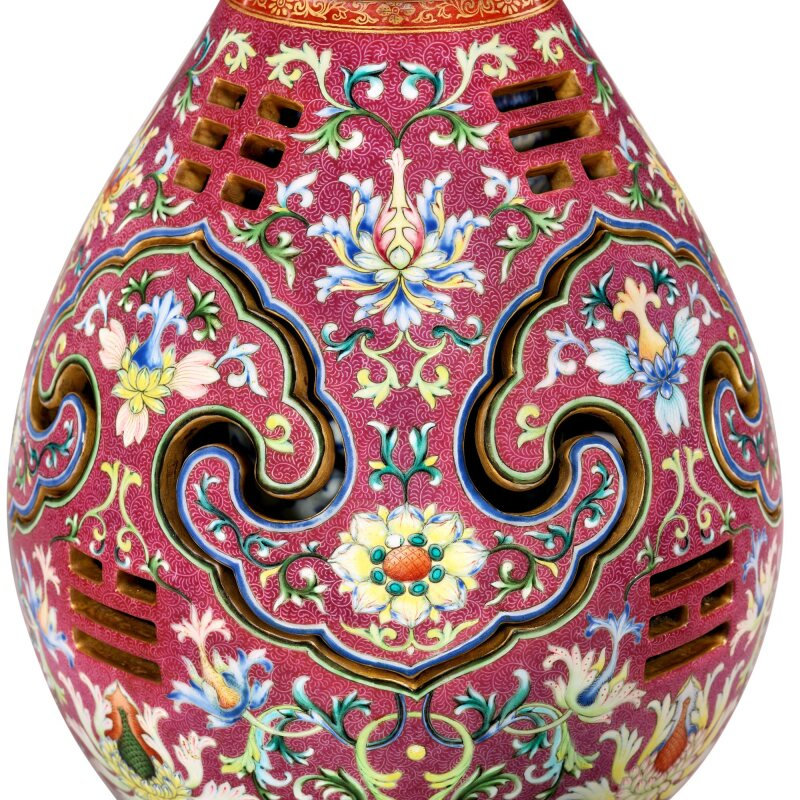

The Dr Wou Kiuan Collection. A Magnificent Ruby-Ground Yangcai 'Trigrams' Reticulated Vase, Seal Mark and Period of Qianlong. Est: HK$ 60 – 120 million / US$ 7.6 – 15.3 million. © Sotheby's 2022

The Personal Collection of the late Sir Joseph Hotung. A Unique and Highly Important Moulded Blue and White Barbed 'Fish' Charger, Yuan Dynasty. Est: HK$ 30 – 50 million / US$ 3.8 – 6.4 million. © Sotheby's 2022

This October, Sotheby’s Hong Kong presents the most significant Chinese Works of Art sale series with the convergence of the finest private collections from the world’s greatest Chinese art collectors including Dr Wou Kiuan, Mr Joseph Lau and Sir Joseph Hotung. The star lot of this season is a Magnificent Ruby-Ground yangcai 'Trigrams' Reticulated Vase from the Qianlong period (Est: HK$ 60 – 120 million / US$ 7.6 – 15.3 million) from the Dr Wou Kiuan Collection Part II, a carefully curated sale presenting six masterpieces from the 18th century. The collection of Joseph Lau, comprising 11 imperial gems, occupies pride of place among the very finest ever assembled in the field. At the heart of Sir Joseph Hotung’s personal collection is an array of masterpieces which charts many of the peaks in China’s long history, from the Neolithic Period to the Qing dynasty. Adding to this season’s strong line-up of renowned private collections are a selection of Ming and Qing jades from the collection of Victor Shaw and a group of archaic artworks from an important Japanese collection.

"This Autumn sale series marks a once-in-a lifetime opportunity for collectors and enthusiasts of Chinese art. Very rarely will you see such a superlative line-up from the world’s most celebrated Chinese art collections. We will be offering fresh to market masterpieces in almost each and every field of Chinese art and this is possibly the most anticipated sale series Sotheby’s has ever hosted." Nicolas Chow. Chairman, Asia and Chairman, Chinese Works of Art.

"These illustrious private collections not only showcase the impeccable taste, vision and passion of this century’s most influential Chinese art collectors, but also offer a window to the extraordinary depth and breadth of Chinese art forms." Xibo Wang, Head of Department, Chinese Works of Art.

A Journey Through China’s History: The Dr Wou Kiuan Collection Part II

Following on from the success of Part I in New York in March and the record-breaking first Hong Kong chapter in April, the carefully curated sale presents six masterpieces from the 18th century showcasing the unparalleled technical mastery in the imperial kilns in Jingdezhen, including a group of enamelled porcelains formerly from the Fonthill heirlooms which have not surfaced the market in around half a century. Highlights include a Qianlong magnificent and possibly unique ruby-ground yangcai ‘trigrams’ reticulated vase, corroborated by the court archives to have been made either in 1743 or immediately thereafter. The vase is a tangible testament to the unprecedented and unparalleled culmination of technical virtuosity in porcelain production between 1741 and 1743, fuelled by an imperial reprimand from the Qianlong Emperor. (Catalogue essay available upon request)

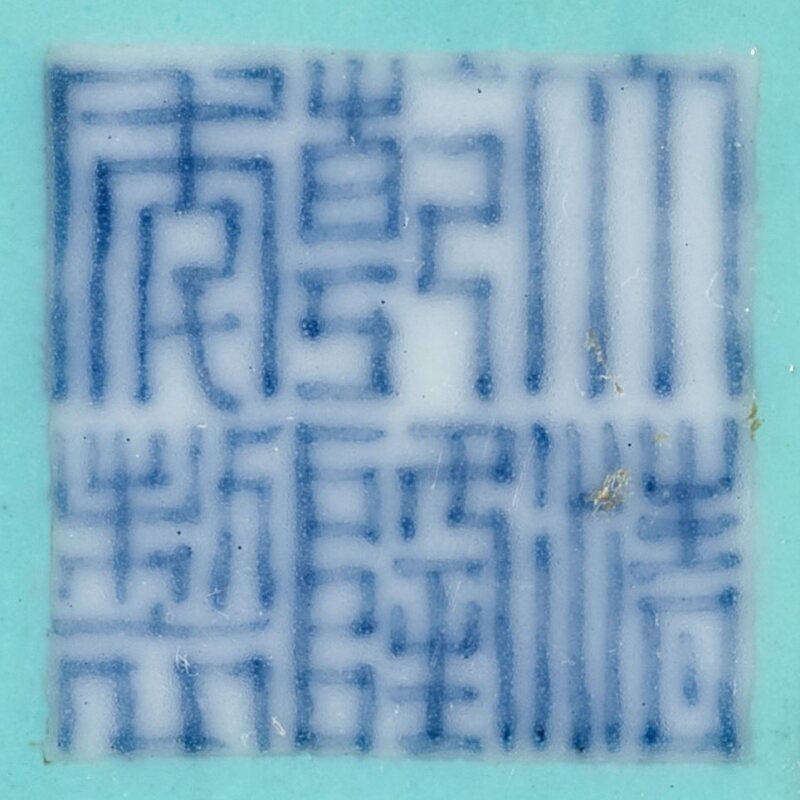

Lot 3801. The Dr Wou Kiuan Collection. A Magnificent Ruby-Ground Yangcai 'Trigrams' Reticulated Vase, Seal Mark and Period of Qianlong (1736-1795). H. 31 cm. Estimate: HK$ 60,000,000 – 120,000,000 / US$ 7,644,000 – 15,287,000. Lot sold: 177,463,000 HKD. © Sotheby's 2022

of pear shape, with a revolving trumpet-shaped neck pivoting on a cylindrical inner vase, the globular body cut along a line of interlocking ruyi-heads and pierced with the eight trigrams, the bright ruby ground finely incised in sgraffiato with dense feather arabesques, reserved with stylised lotus flowers borne on curling foliage issuing additional florets and buds, the spreading foot encircled by a ruyi-band in red and blue against a vivid lemon-yellow ground with similar sgraffiato work, the waisted neck with interlinked ruyi and floral designs on a pale blue and yellow ground, flanked by two flat scroll handles enamelled in iron-red and gilt, the flaring mouth rim with leafy sprays on a pale green ground, the inner vase visible through the narrow openings, painted in underglaze-Soame Jenyns, Later Chinese Porcelain. The Ch’ing Dynasty (1644-1912), London, 1951, pl. CVII, no. 1 and p. 71.

Rose Kerr et al, Chinese Antiquities from the Wou Kiuan Collection. Wou Lien-Pai Museum, Camberley, 2011, cat. no. 154blue with lotus scrolls in early Ming style, the interior of the neck and the base enamelled in pale turquoise green, the base reserved with a six-character seal mark.

Provenance: Collection of Henry Brougham Loch, 1st Baron Loch of Drylaw (1827-1900), by repute.

Collection of Alfred Morrison (1821-97), Fonthill House, Tisbury, Wiltshire, no. 328, probably since 1861.

Collection of the Rt. Hon. The Lord Margadale of Islay, T.D., J.P., D.L. (1906-96).

Christie's London, 18th October 1971, lot 56.

Collection of Dr Wou Kiuan (1910-97)

Wou Lien-Pai Museum, 1971-present, coll. no. Q11.49.

Literature: Soame Jenyns, Later Chinese Porcelain. The Ch’ing Dynasty (1644-1912), London, 1951, pl. CVII, no. 1 and p. 71.

Rose Kerr et al, Chinese Antiquities from the Wou Kiuan Collection. Wou Lien-Pai Museum, Camberley, 2011, cat. no. 154

Heaven and Earth Intertwined

Regina Krahl

It would be hard to find a porcelain vessel that can better embody the artistry and aesthetics fostered by the Qianlong Emperor and the peak of craftsmanship at the imperial kilns in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province. In its outstanding technical intricacy, combining reticulated, interlocking and revolving features, its auspicious design with Chinese symbolism and Western baroque features, and its rich and superbly balanced colour scheme and brocade-style ground, this ceramic work of art is of a sophistication that has never been surpassed. Even this most demanding of patrons, the connoisseur Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-95), who was hard to please, could not have wished for more. Court archives show that this vase must have been made either in 1743 or immediately thereafter, at a period when the Emperor was in his prime and the imperial manufactories achieved their greatest triumphs.

It was only two years before, in the 6th year of Qianlong, 1741, that the Emperor had reprimanded Tang Ying (1682-1756), the most inventive and capable supervisor the imperial kilns ever had, for low quality and breakages in porcelains sent to the court. Since Tang was largely stationed elsewhere, in Huaian and later in Jiujiang, also in Jiangxi, to follow his other duties as customs official, a resident manager, Laoge, was appointed to directly supervise the work at Jingdezhen and to assure consistent high quality. This, however, was not all. The imperial reprimand must have raised serious alarms with Tang and his potters, who knew that they had to come up with something out of the ordinary to recover lost grace. According to Liao Pao Show, the seventh year of Qianlong, 1742, marks a turning point for yangcai ceramics, the exceptional porcelains made at Jingdezhen for the court, mainly between 1741 and 1744 (Liao Baoxiu, Huali cai ci: Qianlong yangcai/Stunning Decorative Porcelains from the Ch’ien-lung Reign, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 2008, p. 39). These few years saw an unprecedented and unparalleled culmination of technical virtuosity in porcelain production.

By the end of the preceding Yongzheng period (1723-35), the manufactories had already explored such a vast spectrum of styles, designs and colours and reached such a level of technical refinement, that it must have seemed virtually impossible to venture beyond; so, the potters had to search far and wide for inspiration. Openwork had already been accomplished much earlier, for example, at the much coarser celadons of the Longquan kilns of Zhejiang province in the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). This probably did not pose too many problems for Jingdezhen’s potters.

Pieces with moveable and interlocking parts were unheard of in ceramics, but existed in jade, where they also were very complicated to realize. Examples can be seen in the Guwantu (‘Pictures of antiques’), two handscrolls depicting works of art, probably from the imperial collection painted for the Yongzheng Emperor (see Regina Krahl, ‘Chinese Jade Before Qianlong’, in The Woolf Collection of Chinese Jade, London, 2013, pp. 52 and 58, figs 8 a and b). To create such forms in porcelain and to fire them repeatedly at different temperatures, first for the porcelain itself, where it shrinks, and then again for the various colours, was a challenge never attempted before. Once it became possible to produce porcelains with detached, interlocking parts, it may have seemed like the natural next step to make these freely moveable and able to rotate. In the following year already, 1743, the potters were successful and the first examples were sent to the court. This delivery included one vase just like the present piece.

On the 21st day in the leap 4th month of the 8th year of Qianlong, 1743, Tang Ying submitted a memorial to the Emperor recording his presentation to the court of a total of nine jiazeng linglong (layered openwork) and jiaotai (interlocking) vases of innovative design, stating that he did not dare to create larger numbers, since they are so expensive to make; yet, he would later, if accepted, make pairs. The Emperor replied that he ought to make pairs for those that stand alone, but that indeed he should keep numbers low and only to submit them for special occasions.

For the 17th day of the 5th month of the same year, there is another record that Eunuchs Gao Yu and Hu Shijia, as proposed by Treasurer Bai Shixiu and Deputy Foreman Dazi, had presented a yangcai red-ground ‘brocade work’ [sgraffiato] reticulated vase with ‘heaven and earth intertwined’ design, for which the Emperor had ordered a fitted stand, which was completed on the 21st day of the same month. Two further pairs are recorded, one for the 30th day, 11th month, 10th year of Qianlong (1745), for which fitted huali wood stands were tailor-made and presented on the 21st day of the following month; the other was presented on the first day, 5th month, 11th year (1746) and fitted stands were submitted on the 18th day of the same month.

The Emperor’s reaction has not been passed on, but circumstantial evidence suggests that he must have been pleased. Not only did he ask for pairs to be made for the singles, in spite of their exaggerated costs, but also he ordered stands to be made as soon as the vases had arrived and asked for them to be kept together with other top-rated artefacts such as falangcai wares in the Qianqinggong, the main hall of the Inner Court in the Forbidden City.

1743 is also the year in which Tang Ying annotated a painted album of the porcelain-making process for the Emperor, who had asked for it (Peter Y.K. Lam, Chinese Ceramics from the Dawentang Collection, Hong Kong, 2019, vol. 2, pp. 270-313). The twenty illustrations and detailed explanations could have left the Emperor in no doubt about the complexity of ceramic manufacture; and he would have seen that the album dealt merely with the regular production that was done on a large scale and showed nothing of the individual treatment and exceptional working procedures reticulated, interlocking and revolving vases would have required. It was only for a few years that Tang Ying managed to get his potters to create such marvels. The level of craftsmanship they commanded and the amounts of manual labour and material they consumed – failures must have been considerable – were excessive even for an imperial workshop, so that even the Emperor advised moderation. It is not surprising that they remain among the rarest and priciest pieces of imperial porcelain today.

With the development of these vases, Tang Ying not only managed to present works to the court that were considered gui fu shen gong (‘demon labour and spirit work’); he also knew how to touch the Qianlong Emperor personally. Trigrams and their message in the Yijing (Book of Changes) appear to have carried important meaning for the Emperor who used the first of the Eight Trigrams, qian, consisting of three unbroken strokes and representing heaven, or the male principle, in his reign title and as such also on works of art and in his seals, together with dragons, long, homophone of the long in his title. In the archives, these vases are referred to as qiankun jiaotai, ‘heaven and earth intertwined’, with qian the first, kun the eighth trigram, and the two together signifying heaven and earth, or the male and female principles. For the Qianlong Emperor, such symbols of a harmonious universe must have felt like a gratifying comment on his own rule.

The inner tube which represents the actual body of the vase, is painted with underglaze-blue lotus scrolls in early Ming (1368-1644) style. A glimpse through the narrow openings in the outer wall thus seemingly offers a view into a distant past – a glorious imperial past, whose natural heirs the Manchu emperors claimed to be.

The strongly Western-oriented painted decoration on the outside of this vase contains a completely different message, but one that the Qianlong Emperor would have welcomed no less. “Nowhere was the multicultural nature of Qing rulership more evident than in the paintings, porcelains, and other objets d’art that were created for palace use and for presentation to officials and embassies. The use of material culture as an expression of the court’s cosmopolitan vision is exemplified in the activities of the Qianlong emperor” (Evelyn S. Rawski, The Last Emperors. A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1998, p. 51).

Although the construction of Western-style palaces in the Yuanmingyuan summer resort had not yet begun, the court had received Western artefacts in many different media through the Jesuits who had been active at the court already in the Kangxi period (1662-1722). Most of these foreign objects, even scientific instruments, were decorated with the floral ornaments that were en vogue particularly in France at the time. Prototypes of the curly foliate scrolls around the lower part of the vase, which Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens calls ‘in European seventeenth-century art … omnipresent’, appear, for example in French tapestry and carpet design, but also in many other media (Michèle Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens, ‘Notes on European Decorative Arts at the Chinese Court during the Kangxi Reign: Importations, Copies and Adaptations’, National Palace Museum Bulletin, vol. 45, October 2012, p. 7, figs 6 and 7a). Idealized eight-petalled blooms with pearl rings around the centre, not unlike the flower-heads in the pendent ruyi panels of this vase, can already be seen on a Kangxi-period brocade in the Palace Museum, Beijing (Kangxi, Empereur de Chine, 1662-1722. La cite interdite à Versailles, Musée national du château de Versailles, Paris, 2004, p. 10, no. 120). Not only the imaginary blooms and leaves and the geometric arrangement of the overall floral design are Western in origin. In parts of the decoration, distinct shading was introduced to create three-dimensionality, a Western painting device that was basically rejected by Chinese painters. On this vase, a veritable trompe-l’oeil effect has been achieved particularly with the rings suspended from ruyi motifs at the neck.

Tang Ying, who had worked at the palace in Beijing himself, was clearly aware of the latest trends in the capital and made sure that Jingdezhen’s porcelain painters adapted their repertoire. These used foreign models as inspiration, but turned them into their own independent, idiosyncratic style – a style that became one of the characteristics of yangcai porcelain.

There exists only one very similar vase, but not the exact pair to the present piece, formerly in the collections of Laurent Héliot and Jack Chia and now in a private Hong Kong collection, sold in these rooms, 17th May, 1988, lot 116 (fig. 1). That vase is very similar in shape, design and size, but has an additional raised rib below the neck, and the two show very minor differences in the painted decoration. One of these vases might represent the first piece delivered in 1743, the other may have been made as a pair to it, but later, after the Emperor had asked for this.

An Imperial Ruby-Ground yangcai 'trigrams' Reticulated Vase, Seal Mark And Period Of Qianlong, Formerly In The Collections Of Laurent Héliot And Jack Chia, Sotheby's Hong Kong, 17th May 1988, Lot 116.

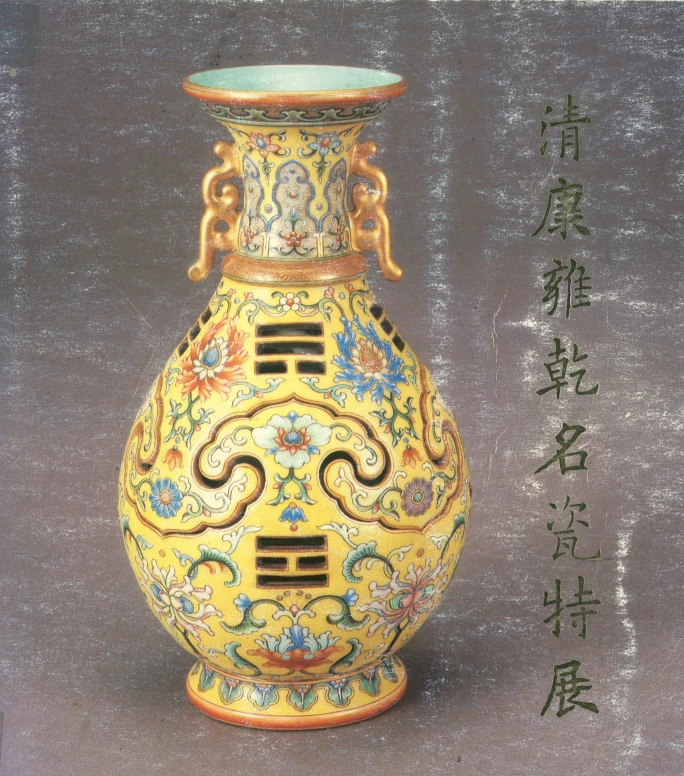

A pair of much smaller yangcai vases (19.5 cm tall) of very similar overall form, construction and decoration but on a yellow ground is in the National Palace Museum, Taipei. It is recorded in the palace archives of 1744. One of them was included in the Museum’s exhibition Qianlong huangdi de wenhua daye/Emperor Ch’ien-lung’s Grand Cultural Enterprise, Taipei, 2002, cat. no. V-27; and again in the exhibition of yangcai wares, see Liao Pao Show, op.cit., cat. no. 73, where both are illustrated together, p. 272, no. 62 (figs 2 and 3). Liao explains the complex workmanship, structure and decoration techniques of these vases, which are composed of four sections: an inner vase, which is connected to the overhanging collar, and two detached parts for upper and lower sections of the outer walls. The inner vase is painted – like on the present piece – with underglaze-blue lotus. She writes “Ingenious designs such as the one in the example here were made to laud the prosperity and peace of the empire during the height of the Ch’ien-lung [Qianlong] reign”.

fig. 2. An Imperial Yellow-Ground Yangcai 'Trigrams' Reticulated Vase, Seal Mark and Period of Qianlong, Made in the 9th year of the Qianlong Reign (1744), Qing Court Collection, Taipei Palace Museum.

fig. 3. Catalog Of The Special Exhibition Of K'ang-Hsi, Yung-Cheng And Ch'ien-Lung Porcelain Ware From The Ch'ing Dynasty In The National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1986, Cover.

An immediate predecessor of this vase can be seen in a yangcai wall vase without any openwork, recorded to have been made in the 6th year of Qianlong, 1741, which is of similar pear-shaped form and decorated with similar Western-style flower scrolls on a ruby ground, but its handles continue further down the body (fig. 4). This had to be modified for the present shape where the neck is constructed as a separate part; see Liao Baoxiu [Liao Pao Show], Dian ya fu li. Gugong cang ci [Elegant and sumptious. Porcelains collected by the Palace], National Palace Museum, Taipei, 2014, p. 163, fig. 30.

fig. 4. An Imperial Ruby-Ground yangcai 'floral Scroll' Vase, Seal Mark And Period Of Qianlong, Qing Court Collection, Taipei Palace Museum.

The present vase has one of the most illustrious provenances for Chinese works of art, as it comes from the ‘Fonthill heirlooms’ of Alfred Morrison (1821-1897) of Fonthill House in Wiltshire in the southwest of England (fig. 5). Morrison’s outstanding collection comprised not only superb Chinese imperial works of art but also Western historical documents, paintings, sculptures and other works. In 1861, he bought a substantial group of Chinese porcelains and enamel wares from Baron Loch of Drylaw (1827-1900), to which this vase may have belonged, but he had added Chinese porcelains to his collection already prior to this major purchase and continued to do so afterwards. Dr Wou Kiuan purchased the vase at Christie’s sale of the Morrison collection in 1971, after which it remained in the Wou family for over half a century.

fig. 5. Unknown Artist, Old House at Fonthill, Wiltshire, between 1800 And 1810, Detail, Watercolor and Graphite on Medium, Slightly Textured, Cream Wove Paper, Yale Center For British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.2.25.

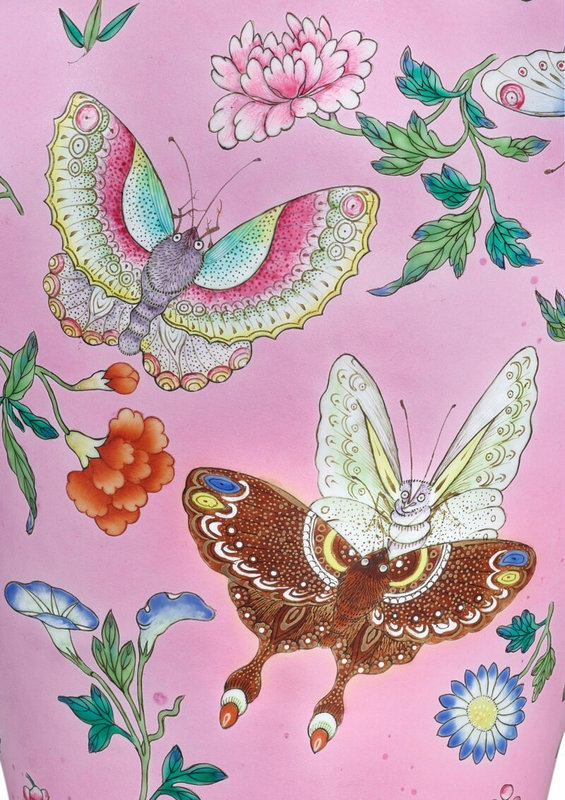

Another highlight also endowed with the Fonthill provenance is a magnificent pair of yangcai ‘butterfly’ vases superbly enamelled on a bright pink ground in a manner imbued with Western influences and fired to perfection.

Lot 3803. The Dr Wou Kiuan Collection. A magnificent pair of yangcai ‘butterfly’ vases, Seal Marks and Period of Qianlong (1736-1795). H. 47 cm. Estimate: HK$ 40,000,000 – 60,000,000 / US$ 5,096,000 – 7,644,000. Unsold. © Sotheby's 2022

each of baluster shape with a tall waisted neck and an incurving lip, the body covered almost entirely in an even powdery bright pink enamel, scattered with a fanciful variety of butterflies and moths in flight among a multitude of flowers, including peonies, magnolia sprays, peach blossoms, prunus branches, lotus flowers, chrysanthemums, orchids and bamboo, the lower part gently tapered and encircled by lappets enclosing a small floret suspending beads and a chime on a café-au-lait ground, the shoulder decorated with arabesque design in blue enamel between a raised gilt band and a turquoise-and-red ruyi- collar, the lips with an additional ruyi-band between gilt lines, the interior and the base covered in a pale turquoise colour, reserved on the base with a six-character seal mark in iron-red.

Provenance: Collection of Lord Loch of Drylaw (1827-1900), by repute.

Collection of Alfred Morrison (1821-17), Fonthill House, Tisbury, Wiltshire, no. 552.

Collection of the Rt. Hon. The Lord Margadale of Islay, T.D., J.P., D.L. (1906-96).

Christie's London, 31st May 1965, lot 107.

Collection of Dr Wou Kiuan (1910-97).

Wou Lien-Pai Museum, 1968-present, coll. no. Q7.34

Literature: Rose Kerr et al, Chinese Antiquities from the Wou Kiuan Collection. Wou Lien-Pai Museum, Camberley, 2011, cover and cat. no. 153.

Regina Krahl, ed., China Without Dragons: Rare Pieces from Oriental Ceramic Society Members, London, 2016, cat. no. 207 (one vase).

Mary Redfern, 'Chinese Without Dragons. An Exhibition Presented by the Oriental Ceramic Society', Arts of Asia, November-December 2016, p. 162, fig. 11 (one vase).

Exhibited: China Without Dragons: Rare Pieces from Oriental Ceramic Society Members , The Oriental Ceramic Society, London, 2016.

Note: This majestic, superbly enamelled pair of vases, with its sumptuous depiction of butterflies and flowers in radiant colours on a rarely used bright pink ground, is archetypical of yangcai porcelains that were produced for a very short period by the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen for the Qianlong Emperor. They are characterized by the phenomenal opulence of their decoration as well as the rich spectrum of their enamels and were amongst the most prized types of porcelain at the Qing court. Yangcaivases were made in very small quantities altogether and of each design, usually only a single piece or a pair was made. It is exceedingly rare to find a matching pair of such vases to have survived and to remain united outside the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, and the present pieces are among the largest specimens preserved.

The term yangcai ('foreign colours') was first mentioned in the final year of the Yongzheng reign (1735) by the renowned supervisor of the Jingdezhen imperial workshops Tang Ying (1682-1756). In his work Tao wu xu lue bei ji [ Records of narrated summaries of porcelain matters], Tang states ' Yangcai vessels [are made with the use of] an enamelling technique new in this reign, borrowing from Western painting methods. [Amongst the paintings of] figures, landscapes, flowers and plumage, there are none that are not fine and enthralling'. About the application of the yangcai palette, Tang writes in his other work Tao ye tuce[Illustrated Album of Pottery], written in the 8th year of the Qianlong reign (1743), that 'round, white-bodied vessels painted in multiple colours and in a style imitating the West are therefore called yangcai . [We] need to select experienced master painters; finely grind and properly mix each type of colour; do trials by painting, colouring and firing slabs of white porcelain; thoroughly understand the properties of the colours and firing, before we can paint from coarse work to fine, and polish the skills from constant practice; a good eye, attentive mind, and exact hand are required to attain excellence' (Liao Pao Show, Stunning Decorative Porcelains from the Ch'ien-lung Reign , National Palace Museum, Taipei, 2008, p. 14) .

Displaying a great variety of butterflies in flight among a multitude of flowers, including peonies, magnolia sprays, peach blossoms, prunus branches, lotus flowers, chrysanthemums, orchids and bamboo, the naturalistic design may have been inspired by European publications, such as the scientific illustrations of the German-born Swiss naturalist and botanical artist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), who studied plants and animals, and in particular butterflies, and published detailed drawings of them – a work that her daughters continued after her death. See a famous book she first published in 1705 on insects in Surinam, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surnamensium , with meticulous depictions of butterflies among flowers and fruits ( fig. 1 ).

Maria Sibylla Merian, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surnamensium, Amsterdam, 1705, Pl. 9., Royal Collection, RCIN 1085787.

Butterflies appeared occasionally on porcelains already much earlier, at least since the Yongle reign (1403-24) of the previous dynasty, as evidenced by a blue-and-white yuhuchun ping (pear-shaped bottle vase), depicting on each side a butterfly hovering above a day lily, preserved in the National Palace Museum, Taipei ( accession no. gu-ci-14975 ). By the Chenghua reign (1465-87), the design began to be painted in colours, as can be seen on some small doucai jars with butterflies between flower sprays, such as one from the Sir Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art and now in the British Museum, London ( accession no. PDF.797). It was not until the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), with the introduction of new palettes and styles brought over from Europe, that the motif began to be rendered in a naturalistic manner. See one of the 'butterfly bowls' of Yongzheng (1723-35) mark and period, painted in the famille rose palette with medallions formed by butterflies and flowers, preserved also in the British Museum, London ( accession no. 1936,0413.26 ). During the Qianlong reign, the motif became more popular . Butterflies and flowers very similar to those on the present vase can be seen, for example, on handled double-gourd vases, such as one formerly in the Yuen Family Collection, included in Selected Treasures of Chinese Art: Min Chiu Society Thirtieth Anniversary Exhibition, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1990-1, cat. no. 166.

Yuhuchun vase with flower and butterfly decoration in underglaze blue, Ming dynasty, Yongle reign (1403-1424), National Palace Museum, Taipei, accession no. gu-ci-14975.

Combinations of butterflies and flowers are not only pleasing motifs, but also replete with meaning, often forming auspicious rebuses to convey happiness, long life, riches, merit and other good wishes. While the Chinese pronunciation for butterfly ' die ' is homophonous with the word ' die ' meaning to 'duplicate', it can be used to double the auspicious wishes expressed by other designs.

Of the present design, a very similar single vase is known, of similar size, differing in details of the decoration and with a graviata ground, also from the collections of Lord Loch of Drylaw and Alfred Morrison, later in the collection of JT and Ping Y. Tai, illustrated in Soame Jenyns, Later Chinese Porcelain: The Ch'ing Dynasty (1644-1912) , London, 1951, pl. CVI, fig. 2, sold at Christie's London, 18th October 1971, lot 65 and again at Christie's Hong Kong, 3rd Dec 2008, lot 2388. None of the many yangcai vases preserved in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, is of comparable size. The Palace Museum, Beijing, owns another yangcai vase painted with similar designs in a similar colour scheme, but of square baluster form, with a pair of archaistic dragon handles ( accession no. gu-154715 ). This bright pink enamel was otherwise rarely used as a ground colour on yangcai porcelains.

Related butterfly and flower designs can also be found on two pairs of yangcai miniature vases with ruby-coloured ground, one in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei (accession nos gu-ci-7373 and gu-ci-7374 ), illustrated in Liao Pao Show 2008, op.cit. , cat. no. 22 and p. 279, fig. 116; the other in the Baur Foundation, Museum of Far Eastern Art, Geneva ( accession no. CB.CC.1930.626 ), illustrated in John Ayers, Chinese Ceramics in The Baur Collection , vol. 2, Geneva, 1999, pls 236-7. Liao suggests that these four vases are the two pairs which, according to the Zaobanchu Huojidang(Archives of the Imperial Workshops), were ordered to be sent to the Qianqinggong, the Palace of Heavenly Purity, one of the main palace buildings in the Forbidden City, Beijing, in the 6th and 7th years of the Qianlong reign (1741 and 1742 ).

Butterflies and flowers are also seen, in other combinations, on a ruby-ground yangcai vase from the collection of George Salting in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London ( accession no. C.1461-1910 ), included in the exhibition China: The Three Emperors, 1662-1795 , Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2005-6, cat. no. 219; and on a blue-ground piece in the Palace Museum, Beijing ( accession no. gu-154599 ), illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum. Porcelains with Cloisonné Enamel Decoration and Famille Rose Decoration , Hong Kong, 1999, pl. 30.

Gems of Imperial Porcelain from the Private Collection of Joseph Lau Part II

The name Joseph Lau resonates with collectors around the globe and it is one that stands for excellence. Chinese art stands at the genesis of Joseph Lau’s adventure with art and it is on Chinese art that he cut his exacting eye before expanding his horizons. Lau assembled one of the finest collections of Chinese porcelain ever, articulated around masterpieces, each representative of the best of a certain period and type, and handpicked from the most prestigious collections.

This season’s offerings include a very fine blue and white porcelain dating from the Yongle period in the early 15th century, the pinnacle of underglaze-blue decorated wares and a period much celebrated for imperial patronage in the arts.

Lot 3507. The Private Collection of Joseph Lau. A Fine Blue and White 'Lotus Scroll' Vase, Meiping, Ming Dynasty, Yongle Period (1403-1425). H. 31.4 cm. Estimate: HK$ 25,000,000 – 35,000,000 / US$ 3,185,000 – 4,459,000. Lot sold: 24,575,000 HKD. © Sotheby's 2022

superbly and elegantly potted with a full rounded shoulder rising at a gently flaring angle from the unglazed base and surmounted by a short waisted neck, skilfully painted in shades of cobalt blue with a wide frieze of lotus scrolls, the flowers rendered set in scene by a network of scrolling steams arranged in curvilinear patterns, between two bands encircling the shoulder and lower body, the first delicately detailed with fruiting sprays of pomegranate, lychee, peach, and crab apple, and the other enclosing flowering sprays of pomegranate, peony, chrysanthemum and camellia.

Provenance: Sotheby's Hong Kong, 15th/16th November 1988, lot 122.

Literature: Exhibition of Chinese Ceramics from the Collection of the Kau Chi Society of Chinese Art, Hong Kong, 1981, cat. no. 62.

Exhibited: Exhibition of Chinese Ceramics from the Collection of the Kau Chi Society of Chinese Art, Art Gallery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 1981-82.

For Emperor, Sultan and Shah

Regina Krahl

A ‘lotus meiping’ is a type of vessel made at Jingdezhen virtually for as long as the kilns made blue-and-white porcelain; but it is the version of the Yongle period (1403-1424), where form and decoration had undergone critical scrutiny and been optimized through court intervention, that became a classic. This early Ming (1368-1644) period has in later periods always been considered the pinnacle of blue-and-white production.

Yongle meiping stand out through their harmonious proportions, which imperial designers had subtly recast compared to the Yuan (1279-1368) and Hongwu (1368-1398) prototypes: The profile became more mellow, curving in a fluid, unbroken line from the narrow waisted neck over the well-rounded shoulder, narrowing down in a gentle curve before flaring again very slightly towards a fairly narrow base. This silhouette makes the voluminous vessel appear elegant, while at the same time creating a satisfactory optical balance and sound physical stability. Yongle lotus scrolls were also refashioned, with blooms and leaves now being accentuated with painted detail, and flowers effectively set in scene by a network of scrolling stems, arranged in complex curvilinear patterns. The peculiarity of this early cobalt painting to form minute dots along the painted brush lines, also known as ‘heaping and piling’, was in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) considered such a charming and indicative characteristic of the best blue-and-white ever made, that it was imitated by the deliberately painting of tiny dots onto motifs in early Ming style, since at that time, the cobalt solution no longer provoked this effect fortuitously (fig. 1). The ‘heaping and piling’ also often caused less desirable dark spots to burn through the glaze surface, but on the present vase, the complete design has retained its beautiful blue colour.

fig. 1. A Blue And White 'Lotus Scroll' Vase, hu, Mark And Period Of Yongzheng, Sotheby's Hong Kong, 8th April 2010, Lot 1875. © Sotheby's 2022

Vases of this type appear to have been universally approved of and are preserved in the palace museums in Beijing and Taipei as well as in the Middle Eastern royal collections of the Ottoman Sultans, still remaining in Topkapi Saray, Istanbul, and of the Safavid Shahs, as preserved in the Ardabil Shrine in Iran. In China, meiping were generally used as storage vessels for wine and some are retaining a cover. In the Ming dynasty, they also seem to have played an important role in imperial burials, where different numbers were apparently granted according to rank. Kong Fanzhi writes (Wenwu, 1985, no. 12, pp. 90-92) that four blue-and-white meiping were reserved for an Emperor's tomb, two meiping, either both blue-and-white or one blue-and-white and one white, for the tomb of an Empress or Dowager Empress, and a single blue-and-white vase for the tomb of a Prince or Princess. Yet, these formulae do not seem to have been strictly adhered to but, whenever possible, exceeded. Four covered blue-and-white meiping were excavated, for example, from the tomb of Liang Zhuangwang, a grandson of the Yongle Emperor, and his wife, who were buried exceptionally lavishly, probably above their station, with massive amounts of gold, silver, jade and jewels.

Liang Zhuangwang died in 1441, his wife in 1451, and their joint mausoleum contained two meiping painted with lotus scrolls between a lingzhi scroll above and petal panels below, and two with lotus scrolls between petal panel borders; one of these had been placed in the tomb’s front room and three in a niche in the back chamber (Liang Zhu, ed., Liang Zhuang wang mu/Mausoleum of Prince Liang Zhuangwang, Beijing, 2007, vol. 1, pp. 74-6, figs 91-3; and vol. 2, pls 9:1, 14 and 72-9). Although many items in the tomb dated from the Yongle period, the meiping were clearly no longer produced under Yongle imperial supervision. Just a few decades later, much of the former excellence had already been lost: the neck is lacking the subtle waisted curve seen on the present vase; the lingzhi-decorated pair in particular has a less generous profile; lotus petals and leaves are rendered in solid colour without any details; and the cobalt blue is darker and much less clear.

The National Palace Museum, Taipei, holds a slightly larger (34.5 cm) Yongle meiping of the present design, which was included in the exhibition Mingdai chunian ciqi tezhan mulu/Catalogue of a Special Exhibition of Early Ming Period Porcelain, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1982, no. 12; a much smaller (24.9 cm) example is in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in Geng Baochang, ed., Gugong Bowuyuan cang Ming chu qinghua ci [Early Ming blue-and-white porcelain in the Palace Museum], Beijing, 2002, vol. 1, pl. 16. In both catalogues, these vases are shown next to smaller Yongle meiping with a different lotus design, with blooms, buds and leaves depicted in a more naturalistic fashion, together with other water weeds, see Taipei, op.cit., no. 13 and Geng, op.cit., pl. 17.

The lotus as depicted on the present vase, with its fanciful curled pointed leaves, is considered as Buddhist lotus, emphasizing its symbolic significance as support of Buddhist deities and representation of purity – rising immaculately clean out of muddy waters – over its sheer aesthetic aspect as embellishment of south China’s scenic beauty. Similar stylized lotus scrolls are in the Yongle period also seen on the mandorla of Buddhist figures depicted in gilt bronze or silk embroidery, on embroidered pendants made to adorn Buddhist figures, on lacquer sutra covers, and in other Buddhist contexts; see James C.Y. Watt and Denise Patry Leidy, Defining Yongle. Imperial Art in Early Fifteenth-Century China, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2005, pls 22, 24, 34, 35.

Vases of this design were probably among the diplomatic gifts transported by the eunuch Zheng He (1371–1433), under whose command vast fleets undertook seven maritime expeditions between 1405 and 1433 to ports all over Asia and as far as East Africa, exchanging presents and tributes; or they may have been exchanged over land by Timurid missions that arrived at the Yongle court from Samarkand and Herat, or the Chinese return embassies to the Timurid empire, led by the court official Chen Cheng (1365–1457). They entered the two important historic porcelain collections in the Middle East, in Iran and Turkey, the former probably through direct exchange, the latter indirectly through later conquests or purchases: a much larger example (41 cm) from the Ardabil Shrine collection in Iran is illustrated in John Alexander Pope, Chinese Porcelains from the Ardebil Shrine, Washington, D.C., 1956, pl. 51, no. 29.409, perhaps the vase illustrated as remaining in the Shrine after the bulk of the collection had been transferred to the National Museum of Iran in Tehran, in T. Misugi, Chinese Porcelain Collections in the Near East: Topkapi and Ardebil, Hong Kong, 1981, vol. 3, p. 353; a vase of the same size and a slightly larger one are recorded in Regina Krahl, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul, ed. John Ayers, London, 1986, vol. 2, no. 623.

Other meiping of this design and of similar size are in the British Museum, London, from the Sir Percival David Collection, included in Margaret Medley, Oriental Ceramics. The World's Great Collections, vol. 6, Tokyo, 1982, no. 104; and in the Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo, illustrated in Chinese Ceramics in the Idemitsu Collection, Tokyo, 1987, pl. 630. Only three such meiping appear to have been offered at auction over the last eighty years or so: one from the collection of Major Lindsay F. Hay in our London rooms, 25th June 1946, lot 61; another, illustrated in Mayuyama, Seventy Years, vol. I, Tokyo, 1976, no. 740, p. 246, at Christie's New York, 20th September 2002, lot 313, and in our New York rooms, 20th March 2007, lot 750; the third in our London rooms, 17th November 1999, lot 744.

A superb and rare early Ming blue and white vase, (meiping) Ming dynasty, Yongle period. Sold at Sotheby's New York, 20 March 2007, lot 750. © Sotheby's 2022

Lot 3505. The Private Collection of Joseph Lau. A fine and outstanding doucai and famille-rose 'sanduo' moonflask, Seal mark and period of Qianlong (1736-1795). H. 31.3 cm. Estimate: HK$ 20,000,000 – 30,000,000 / US$ 2,548,000 – 3,822,000. Unsold. © Sotheby's 2022

the well-potted rounded body superbly painted on each side in the doucai palette accented with famille-rose highlights, rendered with a large medallion formed with the sanduo, comprising a pale yellow bough bearing a two ripe peaches and a third fruit below depicted in raspberry-red shading to a pale greenish-yellow with scattered raspberry markings, a brown pomegranate branch bearing three fruit in soft shades of purple and yellow, the largest with burst skin to reveal the bright purple seeds inside, and with four finger-citron rendered in cobalt-blue beneath the bright yellow enamel, the various boughs interlaced and wreathed by curling foliage, the sides with a swooping iron-red bat suspending a leafy scroll extending to enclose a wan emblem and shou character above a further bat supporting a beribboned and tasselled chime, the cylindrical neck with a bat on each side suspending scrolling foliage and flanked by a pair of handles rendered in the the form of sinuous dragons, all between pendent ruyi heads and a leafy scroll encircling the rim and foot, the base inscribed in underglaze blue with a six-character seal mark.

Provenance: Sotheby's Hong Kong, 8th November 1982, lot 204.

Christie's Hong Kong, 8th October 1990, lot 525.

The Tsui Museum of Art, Hong Kong.

Literature: Geng Baochang, Ming Qing ciqi jianding. Qingdai bufen [Appraisal of Ming and Qing porcelain. Qing section], Taipei, 1984, pl. 165.

Geng Baochang, Ming Qing ciqi jianding [Appraisal of Ming and Qing porcelain], Hong Kong, 1993, pl. 478.

Yeh Pei-Lan, Beauty of Ceramics. Gems of the Doucai, Taipei, 1993, pl. 122.

The Tsui Museum of Art. Chinese Ceramics IV: Qing Dynasty, Hong Kong, 1995, pl. 176.

Note: Rarely have the doucai and fencai (famille rose) palettes been as successfully combined as on this impressive moonflask, which celebrates the creative breadth of porcelain production under the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-95) with its brilliant colour palette. Only one pair of such vases appear to have been produced.

The doucai painting style, with its delicate drawing in fine blue outlines and its colouration in polychrome washes, was the archetypal style of decoration in the Chenghua reign (1465-87), when the colours were still limited to a few bright shades. It was only by the end of the Kangxi reign (1662-1722) that the fencai palette with its wide range of tones and subtle pastel tints became available. The first trials in combining the two colour schemes began in the Yongzheng period (1723-35), but were generally restricted to small touches of fencai enamels included among typical doucai designs.

This moonflask represents a very ambitious combination of the two colour schemes, since the full famille rose enamel palette is here used with the underglaze-blue outlines that are characteristic of doucai. Although aesthetically most satisfactory and striking, the marriage of these two painting techniques remained rare. Featured by Geng Baocang in his famous ceramic book Ming Qing ciqi jianding / Appraisal of Ming and Qing Porcelains, Hong Kong, 1993, fig. 478, this vase is used as an exemplar of the remarkable graphic effect that can be found on doucai wares of the Qianlong reign. An achievement of the Qianlong period, the full incorporation of the doucai and famille rose palettes was, as Geng states, usually applied only to the depiction of flowers and clothes to enhance the overall visual effect. He also notes that this special style continued to be appreciated in the century thereafter, as demonstrated by some of the desk items produced at the imperial kiln of the Daoguang reign (1821-50).

Only one other vessel of this design appears to be recorded, presumably the pair to this flask, formerly in the collection of the British Rail Pension Fund, sold in these rooms, 16th May 1989, lot 87, illustrated in Sotheby's Hong Kong, Twenty Years: 1973-1993, Hong Kong, 1993, pl. 239, and included in the Special Exhibition. Chinese Ceramics, Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, 1994, cat. no. 342.

The design of this piece is known from a closely related moonflask with a wider foot, and handles in the form of bats, which is painted in doucai only, from the collection of Iver Munthe Daae, now in the collection of the National Museum, Oslo (accession no. OK-03389), and included in the exhibition Daae Samlingen, Kunstindustrimuseet i Oslo, Oslo, 1989-90, catalogue p. 38. Thanks to the colours of the famille rose palette, the fruits on the present moonflask that are delicately shaded in layered tones of pink, purple, yellow and lime-green, are represented much more naturalistically compared with those on the Oslo vessel. The skin of the peaches is particularly sensitively painted in a range of gradations and the seeds of the pomegranates are carefully rendered as if reflecting light – effects not available with the doucai palette.

The motif on these flasks is known as sanduo, literally ‘three plenties’ or ‘three abundances’. The idea originates from the main Daoist text, Zhuangzi, of the Warring States period (475-211BC), where in the chapter on Heaven and Earth the philosopher describes the story of the sage Yao visiting a place called Hua, whose local official gives Yao three blessings: ‘May the sage live long’, ‘May the sage become rich’, ‘May the sage have many sons’. The official added that ‘long life, riches, and many sons are what men wish for’. At least from the late Ming dynasty (1368-1644), these three blessings have been symbolically rendered by groups of the three fruits peach, Buddha’s Hand citron and pomegranate. In China, peaches have a long history of being associated with longevity and immortality. The Buddha’s Hand citron (fo shou) consists almost entirely of rind and is therefore not edible, but is used as a medicinal plant. On account of its intense fragrance and evocative form, resembling a hand with fingers bent to form a mudra, it is a popular offering on altars of temples and local shrines. The character fo is also a pun for ‘riches’ (fu) and ‘blessings' (fu), making this fruit highly auspicious. The pomegranate, usually depicted split open and revealing its multiple seeds, represents the wish for many offspring.

Related in its colour scheme and motif, but different in form, is a meiping painted in both doucai and famille rose colours, depicting eight fruiting sprays of pomegranate, peach, finger-citron, cherry, longan, loquat, grape and lychee but in a more dispersed manner, sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 8th April 2007, lot 513.

The shape of the present flask inevitably calls to mind the moonflasks of the early Ming (1368-1644) reigns of Yongle (1403-24) and Xuande (1426-35), the greatest period for the production of blue-and-white porcelain. These Ming dynasty moonflasks began to be copied on a larger scale in the Yongzheng reign, when the whole repertoire of Yongle forms was reproduced. The Yongzheng versions generally follow the Ming shapes rather closely, either with a flat base and no foot, or a garlic-head mouth, while in the present version the shape has been modified. In the Qianlong reign the potters of the imperial kilns appear to have been more interested in diversifying handle shapes than in details of the vessels' silhouette, and animal, bird and plant forms, often archaistic in style, were created. The present handle shape can be traced back to the Yongzheng reign, but at that time it represented a great exception, as otherwise at that time handles were far simpler, generally of plain loop or scroll form, or were lacking altogether.

Hotung: The Personal Collection of the late Sir Joseph Hotung

The late Sir Joseph Hotung (1930-2021) was respected and revered in the art world for his jade collection and for his philanthropy. What is much less known is his discriminating eye for the quality and design, and the personal collection formed at his house in London as a backdrop to his life – seen only by a privileged few. The series of dedicated sales begin in Hong Kong with a focus on the Chinese masterpieces in his collection and are divided into Evening and Day sales. The works on offer, ranging from Neolithic jades and bronzes from Shang – Han dynasties to Ming dynasty furniture and modern Chinese paintings, each represent the most sought-after of their period and type. Highlights include a unique and highly important moulded blue and white barbed ‘fish’ charger from the Yuan dynasty and an important and outstanding bronze male chimera, bixie, from the Han dynasty, the latter endowed with a prestigious provenance and illustration history tracing back to as early as the 1920s in Paris.

This dish is unique and was done with an attention to detail that is exceptional even among this rare group of relief-moulded dishes of the Yuan dynasty. Not only is its relief decoration extraordinarily crisp and detailed, but the popular fish design is here also rendered in a highly individual manner that knows few close comparisons. It is a masterpiece that combines the best and rarest Yuan blue-and-white styles.

Lot 13. The Personal Collection of the late Sir Joseph Hotung. A unique and highly important moulded blue and white barbed 'fish' charger, Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368); 47.8 cm. Est: HK$ 30 – 50 million / US$ 3.8 – 6.4 million. Lot sold: 18,525,000 HKD. © Sotheby's 2022

Fluently painted in cobalt of an inky-blue tone, the central well brilliantly adorned with a single carp swimming amidst swirling eelgrass and other aquatic plants, enclosed within a broad band on the cavetto accentuated by eight peony blooms depicted in full-frontal and profile views , borne on a continuous foliate branch with leaves naturally detailed with veins, all outlined and set against a background of concentric rings resembling cresting waves, the everted barbed rim uniquely moulded with a continuous lingzhi scroll on a contrasting solid blue ground, the exterior decorated with a frieze enclosing a lotus scroll, the unglazed base burnt orange.

Provenance: Sotheby's New York, 9th September 1987, lot 256 and cover.

Eskenazi Ltd, London.

Collection of TT Tsui, Jingguantang Collection, Hong Kong.

Christie's Hong Kong, 29th April 2002, lot 607.

Literature: Sotheby's Art at Auction 1987-1988, London, 1988, p. 258.

Splendour of Ancient Chinese Art. Selections from the Collections of TT Tsui Galleries of Chinese Art Worldwide , Hong Kong, 1996, pl. 48.

John Carswell, Blue & White. Chinese Porcelain Around the World , London, 2000, pl. 5.

Giuseppe Eskenazi in collaboration with Hajni Elias, A Dealer's Hand. The Chinese Art World Through the Eyes of Giuseppe Eskenazi , London, 2012; Chinese version, Shanghai , 2015, reprint, 2017, fig. 78.

Regina Krahl, Early Chinese Blue-and-White Porcelain. The Mingzhitang Collection of Sir Joseph Hotung , Hong Kong, 2022, no. 9.

Exhibited: The Tsui Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1990s.

Fish Within a Cameo of Peonies

Regina Krahl

This dish is unique and was done with an attention to detail that is exceptional even among this rare group of relief-moulded dishes of the Yuan dynasty. Not only is its relief decoration extraordinarily crisp and detailed, but the popular fish design is here also rendered in a highly individual manner that knows few close comparisons. It is a masterpiece that combines the best and rarest Yuan blue-and-white styles.

This dish may be the only example where the fish design is joined with 'negative' decoration in reserved white relief, and the relief design on this dish is spectacular. The moulded peony scroll is unusually lush and was so generously planned that the artisans had to reduce it again slightly before painting the centre, cutting into some of the leaves to create a good circular space for the fish painting. The peonies are extraordinarily intricate, each petal with frilly edges, and petals and leaves with pronounced veining, a far cry from the anhua, 'hidden decoration', known from contemporary white wares, although probably similarly created through impression of the design on a mould into a layer of white slip. The impression of the lace-like white flowers is here so well defined and complex, however, that some details may have been added by hand in form of trailed slip.

A nice detail that visually increases the depth of the design are the two overlapping leaves that are outlined in blue. Even the background against which the flowers are raised was not simply covered with a blue wash but carefully painted with a striated, scalloped wave pattern. The sophisticated organization of the design and the amount of individual manual labour required for its completion are phenomenal. Fish designs were very popular for Yuan blue-and-white dishes, but are almost invariably painted overall in the 'positive' blue-on-white style, with a simple painted flower scroll around the inner sides, and usually have a circular rim, as for example a dish in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC (F1971.3) ( fig. 1) – a treatment that could be accomplished in a fraction of the time by well-trained hands, which could rapidly re-create practically identical pieces on a kind of production line. The present dish exemplifies the laborious technique that creates this cameo effect at its most successful. It was clearly far too labour-intensive to be used more regularly and was therefore soon completely abandoned.

A blue and white 'mandarin fish' dish, Yuan dynasty © Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment , F1971.3.

Fragments of several dishes painted with a fish among water plants have been excavated from the site of the Tughlaq fortress Kotla Firuz Shah, outside Delhi, that had been built in 1354, not much occupied after 1388 and destroyed already in 1398. One among them, apparently with a lotus scroll reserved in white, but probably not moulded, is inscribed in Nastaliq lettering with the term for 'the royal kitchen' (Ellen Smart, Fourteenth Century Chinese Porcelain from a Tughlaq Palace in Delhi, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society , vol. 41, 1975-77, pl. 78b); the others are all painted exclusively in blue on white (ibid. pls 75c, 78c, 79b, 80a, 81a, and a bowl, pl. 90c).

The fish pond motif in the centre of this dish has also been painted with particular care, the carp-like fish being surrounded by a splendid array of no less than six different water plants swerving in line with the fish's movements, two different plants floating on the water surface: the round leaves joined by stems probably represent frogbit, the ones that are divided into four, clover fern; and four submerged: the long swerving leaves, eelgrass; the 'hairy' fronds probably soft hornwort; the fronds with 'hairy ' clusters perhaps chara, and those with leafy clusters, cleavers.

Fish among water plants was a recognized genre of ink painting and was in the Yuan dynasty also used on jars, such as lot 6 , also from the Mingzhitang collection of Sir Joseph Hotung. While the jar, however, shows us something like a cross- section through the water and the air above it, with weeds growing under water seen next to lotus blossoms that are emerging from it, the present scene looks down into the water from above.

With their clear Daoist association in China that is based on a passage in the book Zhuangzi by Zhuang Zhou (c. 369-286 BC), Daoism's leading proponent, fish are considered the manifestation of freedom from restraints, and thus exemplify an ideal always close to the heart of China's intellectuals.

TT Tsui (Tsui Tsin-Tong, Xu Zhantang 1941-2010), the previous owner of this dish, was a Hong Kong businessman, who assembled the Jingguantang collection, a major collection of Chinese works of art, which in the 1990s was exhibited in his own museum, The Tsui Museum of Art, in the old Bank of China building in Hong Kong. He also made substantial donations to museums around the world, in particular The Victoria & Albert Museum, London, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Royal Ontario Museum, the National Gallery of Australia, the Shanghai Museum and the University Museum and Art Gallery of the University of Hong Kong.

Blue and white porcelain in Sir Joseph Hotung's Study.

Lot 1. The Personal Collection of the late Sir Joseph Hotung. An Important and Outstanding Bronze Male Chimera, bixie, Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD); l. 27 cm, h. 18 cm. Estimate: HK$ 6,000,000 – 8,000,000 / US$ 764,500. © Sotheby's 2022

cast in a powerful striding stance, the right front leg stretched forward and the left hind leg extended, the thick paws slightly lifted off the ground exposing sharp claws, its head raised alertly and dominated by piercing eyes and furrowed brows, the ferocious horned beast portrayed with gaping jaws above a tuff of beard, the broad muscular body accentuated with elaborate scrollwork against a ground of swirls and hatching, flanked by feathery wings detailed with striations and terminating in a sinuous tail with feathery protrusions and tufts of fur, the back surmounted by a rectangular and a circular socket incised with concentric circles and triangles, the underside cast with male genitals.

Provenance: L. Wannieck, Paris, 1924 or earlier.

Collection of Baron Adolphe Stoclet (1871-1949), Brussels, 1934 or earlier.

Collection of Madame Raymonde Féron-Stoclet (1897-1963), Brussels, and thence by descent.

Eskenazi Ltd, London, 25th March 2003.

Literature: Michael Rostovtzeff, 'L'Art Chinoise de l'Epoque de Han', Revue des Arts Asiatiques, vol. 1, no. 3, Paris, October 1924, p. 11.

Georges Salles, Bronzes Chinois des Dynasties Tcheou, Ts'in and Han, Paris, 1934, cat. no. 417.

Osvald Sirén, 'Indian and Other Influences in Chinese Sculpture', Studies in Chinese Art and Some Indian Influences, London, 1938, pp. 15-36, pl. III, fig. 16.

Osvald Sirén, Kinas Konst under Tre Artusenden, vol. I: FranForhistorisk Ted Till Tiden Omkring 660 e. Kr., Stockholm, 1942, p. 272, fig. 190.

H.F.E. Visser, Asiatic Art in Private Collections of Holland and Belgium, Amsterdam, 1948, pl. 61, no. 148a.

Georges A. Salles and Daisy Lion-Goldschmidt, Collection Adolphe Stoclet, Brussels, 1956, pp. 390-91.

Chinese Works of Art from the Stoclet Collection, Eskenazi Ltd, New York, 2003, cat. no. 10 and back cover.

Giuseppe Eskenazi in collaboration with Hajni Elias, A Dealer’s Hand. The Chinese Art World Through the Eyes of Giuseppe Eskenazi, London, 2012; Chinese version, Shanghai, 2015, reprint, 2017, fig. 28.

Exhibited: Bronzes Chinois des Dynasties Tcheou, Ts'in and Han, Musée de L'Orangerie, Paris, 1934.

Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, on loan, 1980-93.

Chinese Works of Art from the Stoclet Collection, Eskenazi Ltd, New York, 2003.

Virility to Avert Evil Spirits

Regina Krahl

This bronze animal, although not monumental in size, has a universal sculptural quality that carries it well beyond the confines of Chinese art. With its imaginative, fanciful physique and dynamic quasi-naturalistic bearing, it can hold a place in any history of world art. The basic image of a mighty but not ferocious animal, depicted in a state of utmost alertness that makes one expect an immediate jump or other rapid movement, expresses qualities valued in any animal sculpture and achieved rarely as strikingly as in this figure.

The Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220) is the last period that can still be counted to the Bronze Age, but as bronze was no longer the one material vital for daily life and for ritual, it was increasingly explored also as an artistic medium. When looking at this dramatic sculpture, there can be no doubt that bronze casting had come a long way since its beginnings in the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – 1045 BC), when animals tended to be shown in a distant, awe-inspiring mode. In the late Warring States period (475 – 221 BC) began an interest in animal sculptures rendered in naturalistic poses and movements. This perceived naturalism made mythical creatures, cherished as guardians and benevolent supporters of men, seemingly more approachable.

Fabulous animals springing from an artist’s imagination exist throughout the world. Related winged and horned mythical creatures were depicted already earlier in regions to the west of China and appear, for example, in Achaemenid glazed brickwork from palaces of King Darius (r. 522-486 BC) in Susa, Iran, and are also seen on precious metalwork. In the West, they are usually called chimeras, although the original Greek chimera, also a creature combining features of several animals, was a fictional female monster. In China, several terms were in use at the time for such fanciful beasts, such as tianlu, bixie, or qilin (Ann Paludan, The Chinese Spirit Road. The Classical Tradition of Stone Tomb Statuary, New Haven and London, 1991, p. 42), but the present feline animal with horns, wings and claws is generally known as bixie, which signifies ‘to avert evil spirits’.

In the Han dynasty, such inspiration from abroad would have fallen on fertile ground. Many books of a Daoist nature were circulating, fostering belief in the power of super-natural beings, and the mythological work Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Lakes), probably compiled over a lengthy period prior to and throughout the Han dynasty, described them directly. “The book poses as a guide to travellers visiting holy mountains and other sites within China, informing them of the strange creatures, animal, hybrid, and spiritual, that they may encounter in their wanderings; of the powers that such creatures may wield; and of the consequences of meeting them, consuming their flesh, or wearing their fur” (Loewe in Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe, The Cambridge History of China, vol. 1: The Ch’in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge, 1986, p. 658). Compared to the fanciful creatures described in the Shanhaijing, this chimera, however, seems like a tame version, not that far removed from a real animal.

The visual culture of the period was accordingly also full of mythical beings and demonic figures, inhabiting imaginary realms together with real animals and birds, as for example, depicted on the black-lacquered coffin of Lady Dai, who was buried around 168 BC at Mawangdui near Changsha, Hunan (see Changsha Mawangdui yi hao Han mu/The Han Tomb No.1 at Mawangtui, Changsha, Beijing, 1973, vol. 2, pls 27-31, 38-57). While fabulous animals were frequently depicted in two-dimensional form, sculptures, worked in the round, are rare in the Han. Bronze animals that exist from this time mostly had a practical purpose, being cast as fittings, weights, tallies, belt hooks or supports carrying lamps, incense burners, frames for musical instruments and other items of perishable material which have not survived. Such bronzes were most probably used in daily life, even if some were eventually buried with important personalities.

As a Han bronze animal sculpture, the present chimera is already rare, but the way it is represented is particularly unusual. Its creator – in this case the artist who created the clay model for the casting – clearly aimed to express unbridled masculine vitality which, by association, would render the same to the patron who commissioned it and to any eventual owner, who could identify with it. It depicts an animal at the height of its physical strength. The highly unusual detail of clearly rendered male genitals would probably have remained unseen and were probably never meant to be seen, since this figure was not made for handling and once it was fitted as a support, this would have been impossible in any case. Clearly, this naturalistic feature was the artist’s means of imbuing his bronze with life, of encapsulating in it the virility that would empower the animal with the spiritual energy required to avert evil.

A very similar chimera-shaped fitting, but not its pair, is in the collection of the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (F 1961.3), bought by Charles Lang Freer from J.T. Tai, New York (fig. 1). It shows the same animal in the same pose, but with longer peacock feathers at its wings and tufts of hair at its legs, and with an opening at the back, where it may have had similar sockets. One other similar bronze figure is known, also with sockets at its back, formerly in the collection of Mrs Grace Rogers and included in the International Exhibition of Chinese Art, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1935-36, cat. no. 500, where it is attributed to the Six Dynasties period (220-589).

fig. 1. A bronze fitting in the form of a supernatural animal, Eastern Han dynasty © Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F 1961.3.

The sculptors of these figures have shown the animal in a state of breathless attention, conveying tension of body and mind with muscles and sinews flexed and eyes focussed. Immediately reminiscent in general concept, but capturing nowhere near the bodily energy of the present piece are the monumental stone sculptures of bixie that were placed as tomb guardians on spirit ways in front of important tombs. These massive animals (typically 2.75 m tall, 3 m long) are depicted in the same way as the bronze figures, walking in this other-worldly manner, with only the pads of their feet touching the ground, their toes raised and kept free of the dust of the earth, but their pose tends to be rather static or at best resembling a leisurely walk.

Stone winged animals, but without horns, from an Eastern Han tomb near Luoyang, now in the Luoyang Museum of Ancient Arts at Guanlin Temple, are illustrated in Paludan, op. cit., pl. 36, and in Zhongguo meishu quanji: Diaosu bian [Complete series on Chinese art: Sculpture section], Beijing, 1988, vol. 2, pl. 93; another, perhaps from the tomb of Emperor Guangwu (r. 25-57), is illustrated in James C.Y. Watt et al., China. Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2004, no. 1 (fig. 2). Victor Segalen encountered similar figures in Sichuan (The Great Statuary of China, posthumously published, Chicago, 1978, pls 2 and 3 and fig. F). Several slightly later stone figures of this type are still guarding tombs in the region of Nanjing, capital of the Chinese-ruled south after the Han dynasty; see, for example, one in front of the imperial tomb of Song Wendi (r. 424-53), illustrated in Paludan, op.cit., pl. 59 and in Watt et al., op.cit., p. 25, fig. 22.

fig. 2. A stone winged chimera, Eastern Han dynasty (25-220), found in Mengjin, Henan, in 1992; Luoyang Museum, Henan.

Chimeras carved in jade are also known from the Han period, but are generally rendered in a reclining pose that required less material; one jade bixie of very similar overall form and pose, however, with a single circular socket on its back, was excavated from a Han tomb in a northern suburb of Baoji in Shaanxi, included in the exhibition Tan Shengguang, ed., Yu tian jiu chang. Zhou Qin Han Tang wenhua yu yishu/Everlasting like the Heavens. The Cultures and Arts of the Zhou, Qin, Han, and Tang, Shanghai, 2019, pp. 372-3 (fig. 3).

fig. 3. A jade winged chimera, Han dynasty, excavated from Baoji in 1978 © Baoji Bronze Ware Museum, Baoji, Shaanxi

A very similar horned and winged fabulous creature, but very differently depicted, crouching low to the ground, can also be seen in an exquisite bejewelled gilt-bronze ink-stone box excavated from an Eastern Han tomb of the 2nd/3rd century at Xuzhou, Jiangsu, and now in the Nanjing Museum, see Watt et al., op.cit., no. 5. In the Six Dynasties period, bixie were also depicted in various other media, particularly in China’s southern regions, for example, in green-glazed stoneware, but generally in a much less lively fashion than the present figure.

We do not know what this animal would have supported, but similar circular and rectangular sockets are held by a kneeling winged divine figure cast in bronze, discovered in an Eastern Han tomb at the outskirts of Luoyang, Henan province; see Stephen Little with Shawn Eichman, Taoism and the Arts of China, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, 2000, no. 21 (fig. 4). Animals such as the present piece are by some scholars believed to have served as screen supports.

Fig. 4. A Gold-inlaid bronze kneeling winged figure with sockets, Eastern Han dynasty, 2nd century, excavated from the outskirts of Luoyang in 1987; Luoyang Museum, Henan.

The figure, which is recorded since 1924, formed part of the renowned collection of Adolphe Stoclet and is reminiscent of another bronze animal, perhaps the most famous piece from the Stoclet collection, a large bronze winged dragon figure (fig. 5). This magnificent animal, now one of the highlights in the collection of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, where it holds pride of place, is slightly earlier in date, attributed to the Warring States period, but is depicted in a similarly powerful pose, with similar feathery wings and raised toes, a similar scroll pattern marking its skin, and also represents a fitting. It has been illustrated many times, for example, in Thomas Lawton, ‘The Stoclets: Their Milieu and Their Collection’, Orientations, vol. 44, no. 1 (January/February 2013), p. 71, fig. 5, and was included in the Royal Academy of Arts exhibition, London, 1935-36, no. 489.

fig. 5. A bronze winged dragon, Eastern Zhou Dynasty, Warring States Period, formerly in the collection of Adolphe Stoclet; Louvre Abu Dhabi, LAD 2017.001 © Department of Culture snd Tourism – Abu Dhabi / Photo Mohamed Somji - Seeing Thing Mohamed Somji - Seeing Things/© Department of Culture and Tourism

Baron Adolphe Stoclet (1871-1949), a Belgian banker and industrialist, and his wife Suzanne were highly enterprising art collectors and patrons. The two bronze animals formed part of the vast collection of important works of art from all over the world, on display in Palais Stoclet (fig. 6), an Art Deco work of art in itself, that is still preserved in Brussels. This mansion and its garden had been conceived for the Stoclets down to the last detail by the important Austrian architect and designer Josef Hoffman (1850-1956) and are considered his main surviving oeuvre. Many artists of the influential modernist workshops Wiener Werkstätten contributed to this ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (total work of art), foremost among them the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), who decorated the dining room with a mosaic frieze. A view of the interior of Palais Stoclet with a glass vitrine containing Chinese antiquities is published in Lawton, op. cit., p. 68, fig. 2.

fig. 6. Palais Stoclet, Brussels, Belgium, built by Austrian Architect Josef Hoffmann in 1905-11.

Important Chinese Art including Jades from the Victor Shaw Collection

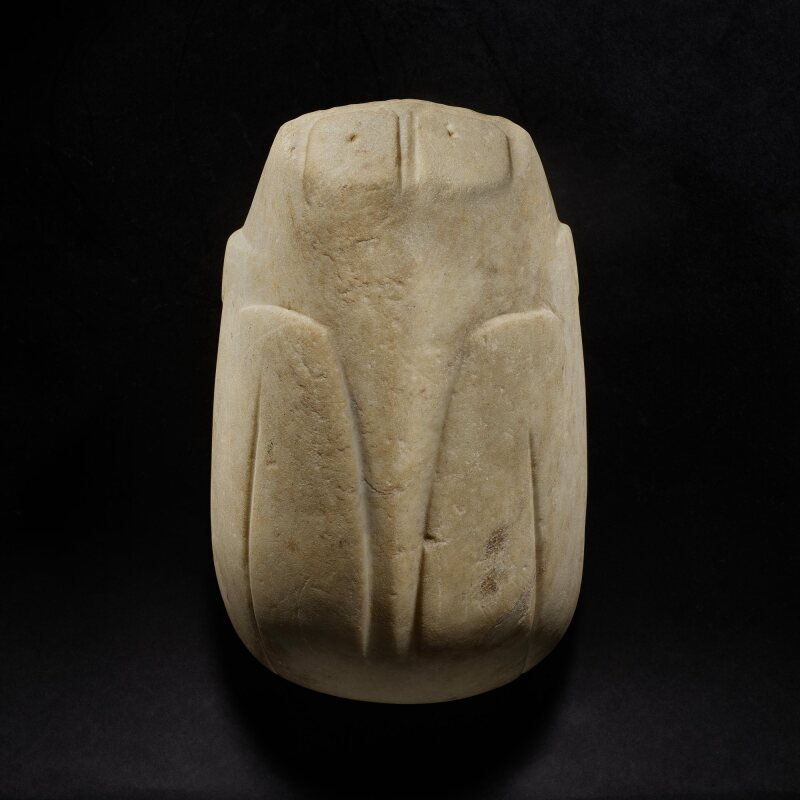

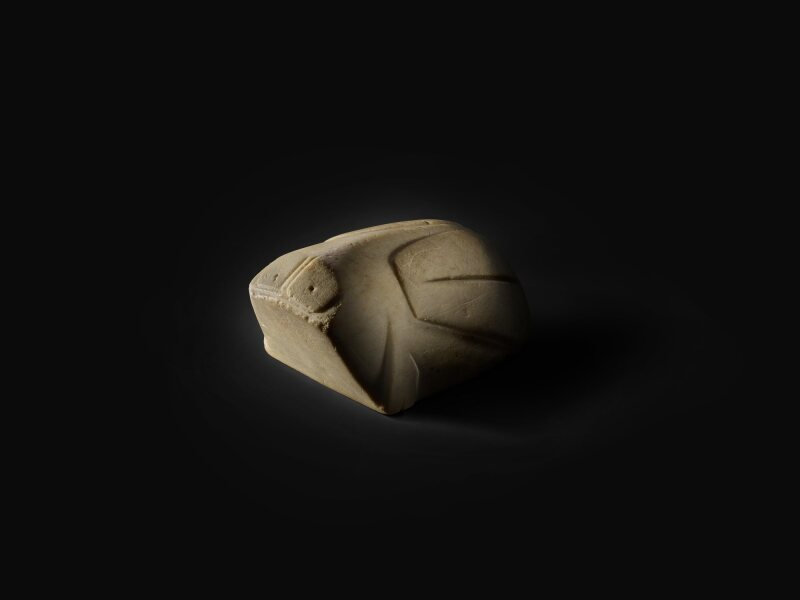

The Important Chinese Art auction presents a tightly curated sale including masterworks spanning five millennia, from the Neolithic period through to the Qing dynasty. Highlights include an extremely rare Qianlong period chenxiang mirror ‘raree’ cabinet and a Shang dynasty marble frog.

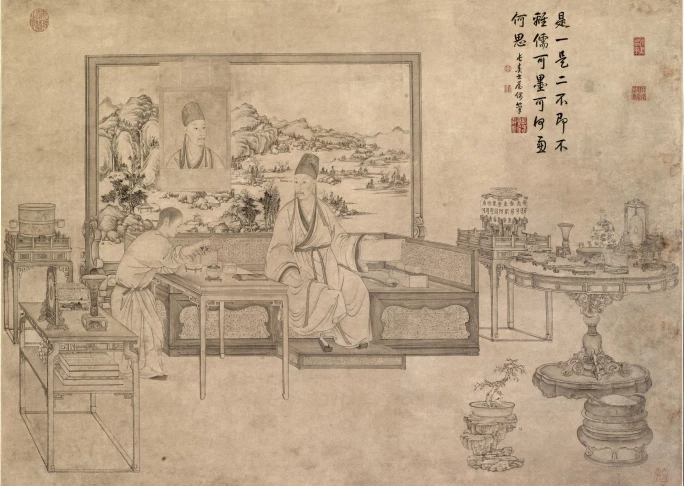

The ‘raree’ box, possibly commissioned in the 17th year (1752), is set with a mirror flanked by two circular holes through which the Qianlong Emperor would have peeped through to view painted pictures, one of which being his most poignant and enigmatically titled double-portrait, ‘One or Two?’ The powerfully carved box cabinet not only showcases the influence of Western mechanism in 18th century court in China, but is possibly the only example known to be employed by the Qianlong Emperor to ponder on the nuances between the literal reflection of the self and self-identity.

Lot 3635. An Important And Superbly Carved Imperial chenxiangmu mirror 'Raree' Cabinet, Qing Dynasty, Qianlong Period, Possibly Commissioned In The 17th Year (1752); 75.5 by 16 by h. 66 cm. Estimate: HK$ 5,000,000 – 8,000,000 / US$ 637,000 – 1,019,000. © Sotheby's 2022

Provenance: A French private collection, South West of France, reputedly acquired in the early 20th century, and thence by descent.

A Rare Imperial Peepshow

The mirror introduces the dualism of illusion and reality. The psychological phenomenon of seeing one’s own reflected image apart from the self is an idea that plays out in folklore and allegory as perhaps the unearthly projection of innermost desires, a glimpse into the soul, or a manifestation of the true ‘I’. Consider this imperial 18th-century “peepshow” mirror cabinet, which was possibly commissioned in 1752, the very type of unusual plaything which the Qianlong Emperor was particularly fond of. We can imagine that when the Qianlong Emperor first approached this Western-technology inspired optical device, he would have encountered a portrait of his double – a looking-glass Emperor conjured through the use of reflections, light and shadow.

The psychological phenomenon of seeing one’s own reflected image apart from the self is an idea that plays out in folklore and allegory as perhaps the unearthly projection of innermost desires, a glimpse into the soul, or a manifestation of the true ‘I’.

The greatest number of imperial portraits were commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), and one possible explanation for his fascination with seeing his own realistic depictions was that he was “repeatedly challenging the boundary between illusion and reality.” (Kristina Kleutghen, ‘One or Two, Repictured’, Archives of Asian Art, vol. 62, 2012, pp. 25-46). In our brief imagining of the Emperor as he sees his own image within the cabinet, it calls to mind the Lacanian “mirror stage” which describes a formative moment of our conscious development when we first become aware of ourselves in relation to the inner and outer worlds.

As the Emperor gazes upon his reflection through the looking glass, he may notice a discreet eyehole to the right of his other self. If he were to peer inside, he would discover his own image – a portrait within a portrait of himself. The peephole vignette reveals the Qianlong Emperor in the garb of a Song dynasty scholar and pictured amidst ancient objects of contemplation.

The image refers to a theatrical design set based on One or Two? – a series of five imperial portraits of the Qianlong Emperor (figs 1 and 2). The portraits are informal but elaborate, depicting the Qianlong Emperor in slightly different scenes, each featuring him as the subject with a portrait of himself within the setting. The five portraits from the series are held in the Palace Museum in Beijing, and the image from optical mirror cabinet resembles them. The name “One or Two?” comes from inscriptions by the hand of the Emperor which accompany the works within the series; the sixteen-character poems vary for each of the portraits, however they all open with the titular question: “Is it one or two?”

fig. 1. One Or Two, changchun Shuwu (Studio Of Eternal Spring) Version, Qing Dynasty, Qianlong Period, Hanging Scroll, Ink And Colour On Paper © Palace Museum, Beijing.

fig. 2. One Or Two, yangxindian (Hall Of Mental Cultivation) Version, Qing Dynasty, Qianlong Period, Hanging Scroll, Ink And Colour On Paper © Palace Museum, Beijing.

“Is it one or two?” ... One interpretation is that his question is a challenge, to understand the nature of the internal and external self which flutters within the liminal space between dream and reality.

The Qianlong Emperor was known to be a fan of mixing influences from the notional East and West, and the historical strand linked to this rare cabinet shows the duality of these worlds. The Emperor reigned over a period of great prosperity, fostering the development of science, art and culture to their height. European missions to the Qianlong Emperor would bring tributes of previously unseen exotic objects, including optical, musical or mechanical instruments. The invention of the so-called “peepshow box” has been credited to the Italian cryptographer Leon Battista Alberti in the 15th-century, and the novelty device reached its popularity in Europe during the 17th century. Through an enclosed cabinet, painted two-dimensional images may be viewed in a way that simulates three-dimensional reality by enhancing the viewer’s sense of the depth. The illusion is created through lenses, mirrors and layering of flat painted panels. Having been presented with such a wondrous device, the Qianlong Emperor perhaps desired to possess his own version with adapted design elements and themes executed by artisans of the imperial court.

Few peepshow cabinets of the time have survived, and an example of this calibre and quality is a rarity. This work reflects the changing taste of the court which welcomed the intersection of design elements from diverse origins. The cabinet is made of agarwood (chenxiangmu) and features ornately carved dragons with a western mercury mirror set. Because agarwood is so precious, artisans tend to use the material sparingly, often joined with some other type of wood. A whole cabinet made from this rare wood is a rare find indeed. Only one other optical toy piece like this one appears to have been recorded. A closely related agarwood mirror cabinet with two peepshow slits shows a Western cityscape and a maritime scene respectively (see below). This rare item was likely restricted to a small circle in the imperial court.

The mystery of this cabinet might reveal an intention far deeper than a novelty of mirrors.

The mystery of this cabinet might reveal an intention far deeper than a novelty of mirrors. We can imagine the unsettling effect experienced by Qianlong Emperor as he saw his image reflected back as spectacle – a subversive relativity of illusion and reality. As the gaze moves back across the mirror and to the left, there is another eyehole which opens to a sublime landscape or a manifestation of a dream. Perhaps it is a vision that projects the Qianlong Emperor forward in anticipation of a paradise beyond.

(This essay was written with thanks to David Ho for his contribution and ideas to the piece.)

After passing through long corridors and grand halls populated by Western-style playthings, the Emperor would have been welcomed foremost by his own reflection when he arrived at this mirror cabinet. Peeping through the two eye slits at the top, he would have encountered his most poignant and enigmatic double-portrait One or Two on the right side, accompanied by a glimpse of paradise on the left. Whimsically designed with overlapping layers of cutout panels, these scenes provide an illusion of three-dimensionality. This powerfully carved cabinet not only showcases the influence of Western theories of optics and perspective at the time but also elicits the view’s literal reflection of the self and self-identity.